1. Introduction

Together

[1.1] Fandom is an extremely generative model for developing flexible pedagogy and for creating more democratic and mutually enriching learning environments. But this requires one to neither other fans as outside of the spectrum of academic thinking nor privilege the work and experiences of fans over other modes of discourse and knowledge production. As Matt Hills has noted, "fandom is not simply a 'thing' that can be picked over analytically. It is also always performative; by which I mean that it is an identity which is (dis)claimed, and which performs cultural work. Claiming the status of a 'fan' may, in certain contexts, provide a cultural space for types of knowledge and attachment" (2002, 11). As such, this performativity enables students and professors in the proper environment to act upon their own sense of subjective positioning relative to cultural and academic texts as consumers, critics, and creators. Learning in this way—from each other, with each other, and through the visible performance of fannish identity—makes the experience more valuable for students and professor alike and elevates everything from discussions to presentations to writing and creative work.

[1.2] This strategy aligns keenly with the experience of fandom and the creative, participatory nature of fans' engagement with their favored materials. Take the parallels between Henry Jenkins's notion of participatory culture, the progressive ideas of John Dewey, and the liberating pedagogy of Paulo Freire as they all relate to experience-based learning:

[1.3] A participatory culture is one which embraces the values of diversity and democracy through every aspect of our interactions with each other—one which assumes that we are capable of making decisions, collectively and individually, and that we should have the capacity to express ourselves through a broad range of different forms and practices. (Jenkins, Itō, and boyd 2015, 2)

[1.4] The plan, in other words, is a cooperative enterprise, not a dictation. The teacher's suggestion is not a mold for a cast-iron result but is a starting point to be developed into a plan through contributions from the experience of all engaged in the learning process. The development occurs through reciprocal give-and-take, the teacher taking but not being afraid also to give. The essential point is that the purpose grow and take shape through the process of social intelligence. (Dewey 1938, 85)

[1.5] The teacher's thinking is authenticated only by the authenticity of the students' thinking. The teacher cannot think for her students, nor can she impose her thought on them. Authentic thinking, thinking that is concerned about reality, does not take place in ivory tower isolation, but only in communication…Liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferrals of information. It is a learning situation in which the cognizable object (far from being the end of the cognitive act) intermediates the cognitive actors—teacher on the one hand and students on the other. Accordingly, the practice of problem-posing education entails at the outset that the teacher-student contradiction to be resolved. Dialogical relations—indispensable to the capacity of cognitive actors to cooperate in perceiving the same cognizable object—are otherwise impossible. (Freire 2018, 70–77)

[1.6] The framing of the three is startlingly similar. Participatory experiences in fandom are about expression, creative discovery, and a kind of communal collective educative practice. Similarly, education built around experience and the breaking down of knowledge hierarchies can harness the organization of a group's knowledge through democratic discussion and process-based learning. These structures promote social intelligence and liberated education, thereby engendering within the classroom the same sense of community and learning together that fandom implies.

[1.7] To buttress this idea of a classroom space constituted of participants working creatively and collectively to develop communal and social intelligence, we have elected to delve into both sides of the student–professor dynamic in order to reveal through our two voices the different perspectives that came to fruition in a particular pedagogical experience. We employ participant observation, an articulated methodology within fan studies. Our study's emphasis on the dual-voice asserts a dynamic apparent within fandom, which was purposefully generated within the course structure as well. Furthermore, we show how the seemingly stark distinctions between a fan-scholar and scholar-fan (Hills 2002, 19) can be collapsed through an experimental and participatory environment that questions generalized perceptions of what it means to do academic work. Through the generation of a place where students and professor can work together, the passions usually ascribed separately and differently to fandom and academic pursuit can be seen as if not in fact the same then at least similar, complementary, and mutually beneficial.

[1.8] "Science Fiction: Humanity, Technology, the Present, the Future" (SF:HTPF) (note 1) is a course taught regularly at XE: Experimental Humanities & Social Engagement (http://as.nyu.edu/xe.html), a stand-alone Master of Arts program in Interdisciplinary Studies housed in the New York University (NYU) Graduate School of Arts and Science. One author (Kimon Keramidas) discusses the course from the professor's perspective and the other author (Fiona Haborak) from that of a student in the class and graduate of the program. We feel that the most important points are made in our descriptions of those moments of in-between where student and professor come together and find a place undefined by roles. We discuss how this condition comes to be not because of educational structuration, course design, or academic pretense but rather because of the enthusiasm of being hopeless, helpless, passionate fans.

2. The course

Fiona

[2.1] Participation in the graduate classroom expresses how a person might experience fandom by maintaining a studious balance between fan studies and active involvement in fan practices. SF:HTPF uses the experience of fandom as a model to develop a pedagogical approach that embraces participatory and creative approaches to project development. Participation and interactivity influence the development of a think-space project where students flesh out a prototype that reimagines a science fiction text. Website commentary, prototype progression, and conceptualization of the project demonstrate how a fan might experience content. Student workspaces on the SF:HTFP website illustrate the capacity by which we can use fandom as a model for the development of academic practice in the classroom. Fannish practices and students' connections to different realms of fandom are encouraged through Geek of the Week presentations and the final project, which reimagines canonical material as a digital, interactive experience.

[2.2] As a result of pursuing higher education, I yearned for a program like XE to grant me creative freedom within an academic setting. Through scholarship, I aimed to apply praxis to critical research. I enrolled in SF:HTPF to foster my love for science fiction lore. Reflecting now as an XE graduate and independent scholar, I sought out cumulative experiences by studying fan practices to influence the development of my MA thesis. I was interested in how to examine and flex theory to dismantle and to deconstruct the canonical texts drawn from the classroom. Passionate enthusiasm motivated my desire to engage in this type of play.

Kimon

[2.3] "Science Fiction: Humanity, Technology, the Present, the Future" came to be at the fortuitous intersection of programmatic experimentation and professorial enthusiasm fueled by the fires of fandom. XE explores sites of inquiry where interdisciplinary study can be combined with pedagogical experimentation. Furthermore, by encouraging graduate student projects with creative components, the students and faculty work in an environment where a range of different media can be both a field of study and a platform for intellectual expression. In this way the freedom of creativity is combined with academic rigor, encouraging knowledge production that addresses a complex range of cultural, social, political, and economic circumstances in a wide variety of media forms.

[2.4] My colleague Robin Nagle and I developed SF:HTPF by using our disciplinary specializations as a starting point to explore our fan interests. Robin is an anthropologist, and I am a cultural historian of media and technology, so we decided to approach science fiction through a frame proposed by Ursula K. Le Guin in the introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness:

[2.5] This book is not extrapolative. If you like you can read it, and a lot of other science fiction, as a thought-experiment…The purpose of a thought-experiment, as the term was used by Schrodinger and other physicists, is not to predict the future—indeed Schrodinger's most famous thought-experiment goes to show that the "future," on the quantum level, cannot be predicted—but to describe reality, the present world.

[2.6] Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive. (1980, xii)

[2.7] Embracing the notion of science fiction as descriptive, the course asks students to not only read, listen to, and view a variety of texts but to think about the historical contexts within which each author was working and how the author might be describing their present in their depictions of the future of humanity and technology. More than a comparative literature review, the course is meant to consider the historical role of science fiction as a genre for commentary.

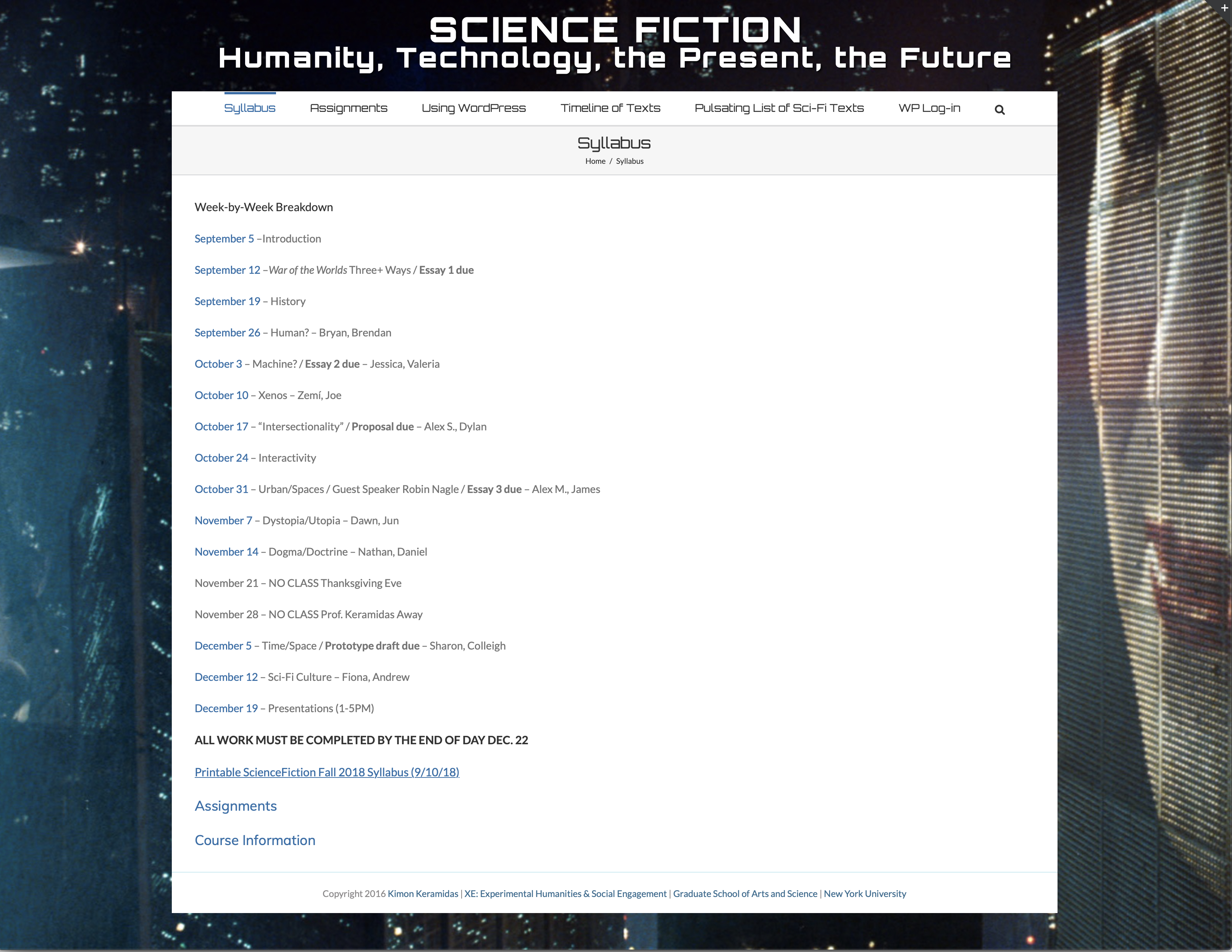

[2.8] The syllabus is broken into weekly topics such as "Human?," "Machine?," "Intersectionality," and "Utopia/Dystopia" with science fiction texts from a variety of media accompanied by theoretical essays and commentary (figure 1). The students begin by reading about the history of science fiction and the contested nature of the term and then encounter a session dubbed "War of the Worlds, Three+ Ways." This week highlights the contextual approach of the course by showing that each text not only bears the markers of the author(s)' perspective at the time of composition but that the same text adapted by multiple authors can show different contextualizations based on the time and place of each adaptation. Students read the original The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells from 1898, listen to the 1938 radio play adaptation by Orson Welles, and watch either the 1953 movie directed by Byron Haskin or the 2005 film directed by Steven Spielberg. Combining reading, listening, and watching, this assignment introduces students to the different kinds of texts and media experiences that we engage with during the semester. Furthermore, the class gets to see how the different producers/directors of the 1938, 1953, and 2005 versions reinterpret and adapt the same text to make it more relevant to the world in which they and their audiences are living.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the syllabus page for the fall 2018 iteration from the course website (http://kimon.hosting.nyu.edu/sites/science-fiction/syllabus-2018/).

[2.9] In Orson Welles's 1938 radio play we see this classic invasion story used to highlight the global tensions and apprehensions being felt around the world at that time. Welles's choice of staging his adaptation over the radio also highlights his awareness of the rapid expansion of media culture at the time. The 1953 movie takes us into the nuclear age and the burgeoning Los Angeles metropolitan area. The walking tripods have been made more futuristic as hovering craft, and the effects used for the Martians' deadly heat rays evoke the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Spielberg's 2005 version brings us a film occurring in the tristate region around New York City, and it is clearly marked by the trauma and imagery of 9/11 (including collapsing buildings, crashed planes, and the visible deaths of scores of civilians). Furthermore, the biological implications of the invasion are more heightened in an era of biowarfare and increased knowledge of DNA and immune system frailties.

[2.10] Although these works come from institutional media production companies and are not works of what is considered fan fiction, they nevertheless open the students' eyes to the new possibilities that individuals imagine when they encounter a text they feel passionate about. In fact, this week in part serves to blur the line where possible between overly codified categorizations of institutional adaptations versus resistant fan works. Students can for themselves begin to think more critically about how fandom is experienced in different levels of cultural production and how they may wish to situate their own work as fannish. As such, "War of the Worlds Three+ Ways" accomplishes two things to consider the influence of fandom as a motivator for intellectual engagement and creative expression. First of all, it shows concrete examples of how the same core story can resonate so differently during different eras. This framing provides students with a methodology by which to approach the texts covered in the class. Second, the three adaptations are models for the course's final project, a prototype of a nonlinear user-driven experience based on an existing science fiction text. Later on we discuss further how the finesse of institutional adapters has analogs in more fan fic–based adaptations, particularly in Fiona's work on the H. G. Wells novel The Island of Dr. Moreau ([1896] 2002) for the prototype assignment.

Fiona

[2.11] As per my impression, the student experience resulted in animated class conversations similar to the roundtable discussions that often occur at mainstream fan conventions. The students conveyed enthusiasm for the media objects they adored while others contributed to the conversation by applying critical theories as relevant to personal interests. The course's structured rigor and critical pedagogy were enhanced by Geek of the Week student presentations (to be discussed in more detail later) through which the class was exposed to material beyond the syllabus and instructor's guidance. Through this journey, we came to see that by imposing a vast cultural influence, science fiction can operate as a conduit for commentary and change (Gunn and Candelaria 2005).

[2.12] As we mentioned in the introduction, the classroom embodied elements of a participatory culture: "a culture with relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one's creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices" (Jenkins, Itō, and boyd 2015, 4). This solidarity serves as a lively undercurrent for the communal component of participatory cultures. Additionally, participatory culture "describes the new role users have assumed in the context of cultural production" (Schäfer 2012, 10). Encouraged to prosper and to share content from their respective fandoms, the students encompassed the role of media users, drawing connections from the assigned texts and showcasing the rigor of fans. The classroom thrived on sharing content, contributing to the website by posing questions online, and hosting a series of animated discussions pertinent to the course material. The solidarity exhibited within fandom became apparent in the classroom as well. As a result of this exposure, the students cultivated both the interest and the inspiration to drive forward their passions in the conception of the prototype and the Geek of the Week assignment.

3. Geek of the Week

Kimon

[3.1] The Geek of the Week assignment Fiona has alluded to was developed as a fan pedagogy solution to a fan pedagogy problem. As Robin and I eagerly set out to select texts for each week, we realized almost immediately that our particular lists of must-sees and must-reads did not have much overlap. Despite being equally ecstatic about the genre, we were not fans of enough of the same things, were loath to let go of our darlings, and soon had a list of over one-hundred books, films, TV shows, and games that each of us insisted had to be included. We were in need of a solution. We knew that we were fans of the genre, but more importantly we knew that the classroom would also be full of fans who were eager to express their fannish identity in myriad ways. So we checked our academic egos at the door and came up with the Geek of the Week.

[3.2] For the Geek of the Week (GotW) assignment each student was responsible for leading part of the discussion for one class meeting. In preparation for leading this discussion, each student would select one additional text from any form of media to be added to the syllabus and would prepare questions to begin the conversation in class. These student choices would be added to the one or two core texts and theoretical essays Robin and I were able to agree upon for each week. For the sake of time, GotW selections were necessarily limited in length to short stories, films, one or two episodes of a TV show, or a video clip, but their connections to the students' fannish passions would make them invaluable.

[3.3] The GotW presentation and its accompanying discussions turned the classroom into what James Gee calls "affinity spaces." Gee's affinity spaces are where fan communities informally gather to discuss video games and share resources online, helping each other to achieve and voluntarily sharing their enthusiasm. Not all of Gee's traits for affinity spaces map to the GotW (mostly because affinity spaces tend to not have the mandatory structures of a classroom), but many do: newbies and masters and everyone else share common space; content organization is transformed by interactional organization; both intensive and extensive knowledge are encouraged; both individual and distributed knowledge are encouraged; and leadership is porous, and leaders are resources (Gee 2004). Henry Jenkins further connects this idea of affinity spaces to the alternative learning environments of participatory culture, noting that unlike traditional top-down academic environments "informal learning within popular culture is often experimental…[and] innovative" (Jenkins et al., 2006, 9). Jenkins's goal here is to note that in such a media-driven culture, cultural consumers can feel comfort and engagement in spaces that provide them with more ownership, agency, and connection to their passions.

[3.4] Incorporating these features of affinity spaces and participatory culture through the GotW made the assignment a hugely important part of what made the class function effectively. The weekly presentations ramped up student engagement, promoted rich conversations, and put science fiction fandom front and center both as a motivator for the class and as an important facet for more fully understanding the genre and its historical and current place in society. Furthermore, the GotW allowed the class to develop into the kind of cooperative enterprise Dewey (1938) described: shaped by the shared social intelligence of all those involved. By purposefully giving over ownership of the class to the students and allowing them a space to participate in fandom, the GotW drove the class on a weekly basis, making each student's investment of time and energy in the class feel more worthwhile.

[3.5] Importantly, opening up the course to the group's individual fannish interests made each student's personal history influential in the classroom. Because NYU in general has a diverse student body—XE even more so, due to the creative and experimental structure of the program—the students' voices represented a wide range of experiences and perspectives from across the intersectional spectrum and from around the world. The course, which admittedly was designed by two cisgender, straight, white, American-born faculty, is changed each semester by the contributions of LGBTQ+, BIPOC, and international students. These students greatly enrich the course materials by sharing texts that they feel represent their view of the world and works of authors that are commenting on places and times that are meaningful to them. The GotW content that has validated the value of this model has included the antidictatorial, anti-imperialistic graphic novel El Eternauta by Argentinian Héctor Germán Oesterheld; queer analysis of the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "Rejoined," which televised one of the first kisses between two women; and the diverse, multilayered, pansexual, pangender, android stylings of Dirty Computer—an emotion picture* by Janelle Monáe. In addition, the significant cohort of Chinese students who have taken the class have provided a unique perspective on the genre. In particular these students have introduced the class to authors such as Cixin Liu—one of the most if not the most highly regarded Chinese science fiction authors—and provided a unique perspective on texts from other countries, particularly Japanese anime. This alternative perspective on Japanese works is particularly important because of the very different historical relationships that the People's Republic of China has had with Japan relative to Western countries.

[3.6] The influence of student contributions and participation through GotW does not cease at the end of the semester—the syllabus is flexible and is adjusted every time the course is offered to respond to texts that students previously presented in class. Furthermore, the discussions factor into alterations based on changes in the understanding of the history of science fiction as well as the increasing importance of global conditions such as climate change, globalization, and human rights. Particularly impassioned and heated conversations about race and sexuality have led to a complete overhaul of the "Intersectionality" week, such that the assigned texts now all come from previous GotWs. In addition, student interest in climate change and so-called Cli-Fi has become increasingly visible and central to class discussions. The week "Urban/Spaces" has shifted from a study of cities to one focused on a better understanding of humanity's relationship to a changing Earth and how authors perceive our ability (or lack thereof) to come to terms with the fact that that change is due to humanity's actions. The contributions of the students' deep engagement as fans through the GotW has been key to the success of the course. The best way to show that is through Fiona's own experience as a participant in and leader of GotW sessions.

Fiona

[3.7] Through each GotW, fandom became a useful pedagogical framework within the classroom. Beyond the professor-student dichotomy of the course, fans yearned to teach and to learn from fellow fans. Each presentation exposed me to a multitude of theories and criticisms to be later integrated into my work. With a fixation pulling from experience, students learned through creation by drawing conclusions based on participatory research as exemplified by Axel Bruns's notion of produsage, which depicts "collaborative engagement of (ideally, large) communities of participants in a shared project" (2008). To expand on this concept, the students converged as a community, participating in each of their peers' body of work. In the context of produsage, the student (as produser) cultivates a GotW segment, which allows the presenter to "feel in control of their participation, and in control as participants in the wider community" (Bruns 2008).

[3.8] Connected by the thread of participation, peer cross-disciplinary interests radiated within the articulation of each GotW segment. Surrounded by colleagues engaged in aspects of fandom, our enthusiasm drove the course because, in our nature, "we are fundamentally social beings, and in the absence of strong evidence to the contrary, the default hypothesis is like us" (Heeter 2000, 7). The makers of the class shared their personal joys to enrich our involvement, drawn from their lived experiences. As a cosplayer, I shared my appreciation for the craft by providing a personal account and historical context. In fusing my interests with my research, I must maintain a balance between being a fan and being a researcher; in doing so, my work has sought to invoke the working practice of participatory cultures in an experimental nature, exceeding the binaries of "fan-scholar" and "scholar-fan" (Hills 2002, 19) to explore a muddied territory in which my personal interests became supported by a vast array of theoretical analysis and methodologies. Therefore, I composed a model based on the work of my peers in which I learned from the ethos that each colleague shared.

[3.9] To an extent, fandom requires participation. When approaching the GotW and prototype assignment, students shared their relationship to their chosen cultural texts. Indeed, each student approached the task by crafting "meaningful patterns out of experience and we spend our lives acquiring, refining, elaborating, and reinventing these patterns" (Murray 2012, 17). Building on preexisting modes of thought and social constructs, my peers dabbled in fannish activities by talking through theories grounded in gender studies, sociology, critical analysis, and so forth. Critical theory fosters a relationship through the texts, real-life experiences, intellectual influences, and discourse. Enthusiasm, with intellectual intrigue, strongly shaped the classroom dynamic.

[3.10] As exemplified by GotW and the prototype assignment, the students as "fans expand these artefacts not only by contributing to discussions and debates, but also by creating related media texts" (Schäfer 2012, 46). The students took an object to discuss at length as a digital and verbal presentation. On September 26, 2018, for the "Human?" section, one of our classmates assigned David Cronenberg's 1986 film The Fly. The film, which radiates the failure and hubris of man, depicts a fusion between science fiction and horror. In The Fly, by tinkering with his teleportation device the scientist Seth Brundle manipulates ethical boundaries, thereby pushing and testing the constraints of humanity (Gomel 2011, 339). Using The Fly as a body of work to digest and dissect encouraged my peers and myself to connect these GotW segments to the assigned theoretical texts. Critical analysis, embodied as invigorating discussion during class, paralleled the performative nature of fandom in which canonical material is studied, deciphered, and interpreted in an animated setting.

[3.11] With participation in fandom operating as a pedagogical device in the classroom, another GotW segment painted a portrait of students behaving as fans. For example, one student used the multiplatform, first-person shooter video game BioShock (Levine 2007) as their GotW for "Dogma/Doctrine" on November 14, 2018, and we were encouraged to view a Let's Play video that documented a run-through of the game or to experience the video game firsthand. This demonstrates the vast diversity of access points across fandom alongside the great influence science fiction has over various media formats as a "feedback loop of images and ideas" (Gomel 2011, 340). Herein, explicit participation pertains to modalities of fan cultures (Schäfer 2012, 52). In other words, when they presented a media object, the students controlled the course participation while we examined their personal placement as a fan; in every aspect, the students performed or demonstrated their fannish proclivities. In accordance with Hills's perception of an affective definition of fandom on a cult level, fandom behaves "as an intensely felt fan experience" (2002, 11).

[3.12] Inspired by the interpretations of my peers, driven by my zeal for cosplay, and motivated by my desire to contribute to fan studies, for the theme week of "Sci-Fi Culture" I created a GotW devoted to cosplay—a physical embodiment of fannish activity. In particular, by embodying science fiction as "the literature of change" (McKitterick 2010), the presentation on The Fly inspired my desire to wed the tension between science fiction and horror in my conceptualization of a "scare attraction" for H. G. Wells's The Island of Doctor Moreau.

[3.13] In his 2016 TED talk "My Love Letter to Cosplay," Adam Savage states, "Everything that we choose to put on is a narrative, a story about where we've been, what we're doing, who we want to be." Savage, known for his role on the series MythBusters (Discovery Channel, 2003–2016), has harnessed experimental methodologies to tell stories—and is also known for roaming the convention circuit in costume. Savage attests to the story of the fan paying tribute to beloved fandom. By contrast, Suzanne Scott has addressed how labor is gendered within fan production in the context of cosplay as a site of fan practice (2015, 146). Through media consumption, cosplay presents "a gendered vision of fan participation that problematically assumes that all fans are driven by a desire to professionalize" (148)—that is, the underlying assumption that fans use cosplay as a vehicle for monetization. As a cosplayer, my narrative and GotW presentation emphasized the manipulation of the body, the complications of identity, and practices within fan culture. Wearing a costume insinuates a performance and imposes a relationship onto the cosplayer's body. In "Costuming as Subculture: The Multiple Bodies of Cosplay," Nicolle Lamerichs argues that to channel this character portrayal "the fan performer relies on multiple bodies and repertoires that are intimately connected to the fan's identity and the performed character" (2014, 113). Overall, my GotW grounded my desire to explore the intersection between performance and fan identity before exploring the do-it-yourself methodology evident within my interactive prototype.

[3.14] Although various fandoms were discussed, dissected, and analyzed, we all remained mindful of the identities claimed and cultural work performed in fandom. By focusing on the subculture, in the merit of self-interest, I echo the sentiments of Henry Jenkins: "Can we, or should we, be 'critical'?" (2006b, 11). Being critical as fans and as students fostered intellectual discussions to reevaluate our views and ideology. Through these GotW segments, I discovered how I behave as a fan within a scholarly setting; the irony was not lost upon me that "fans, by this definition, are those who gather together regularly to experience mass culture but who also respond to its professionalization by creating local, participatory, and amateur group activities for themselves" (Coppa 2013, 77). By harnessing various pedagogies to embrace the personality of a budding scholar, my presentation sought to historicize cosplay and divulge my personal narrative to welcome discussion. I intended to navigate cosplay beyond the convention space. I investigated theories on performativity, both in my GotW segment and in the prototype phase. Therefore, I assigned two pieces for introspection: a video addressing the heart of cosplay and an article assessing its performative nature. Cosplay exhibits signs of fan labor, production, and participation (Scott 2015). Beyond the example of cosplay as a mode of fan production, my GotW assignment explored performativity identities and the virtuosity of art practices involved.

4. The interactive prototype

Kimon

[4.1] The course construction, selection of texts, shaping of discussions, and GotW all led to the final assignment of the course: the development of a prototype for a nonlinear, user-driven, interactive version of an existing science fiction text. The goal of this exercise was twofold. First, students had to re-envision their chosen text from the perspective of the present using the anthropological, historical, and critical analyses we developed during the semester. Second, students had to think of how they could use their new medium of choice to convey the rich, rigorous, and intellectual ideas of the original text but using nonlinear, user-driven story mechanics.

[4.2] The project consisted of three stages: the proposal, the prototype, and the reflection paper. The first stage, the proposal, comprised a 1,000-word or longer statement that provided a description of the original text and its sociocultural and historical contexts; justification for the alternate version, which explained the new sociocultural/historical contexts; engagement with relevant theoretical perspectives as they apply to the original work and new version; and a work plan. The second stage, the prototype, was the core of the project. This multimedia expression would include visual representations of different locations, plot points, and experiences through the use of audio, video, locational, and other sensory expressions. These features were to be conveyed through a combination of drawing, collage, screenplay, storyboard, or other mode and to be accompanied by textual descriptions for further clarity. Although the prototype did not necessarily have to be interactive itself, it had to explicate how interactive mechanics differentiated the work from linear narrative structures. Finally, for the reflection paper, each student was responsible for a statement describing the purpose of the project in relation to the original text, along with historical placement of the project relative to other texts and theory in the field. Each student also was responsible for reflecting on the process of working on the prototype, including descriptions of how disparate media forms affected her workflow, how she approached the different stages of the project, unexpected obstacles or discoveries, and so on.

[4.3] This multistage project challenges students to think creatively, to put theory into practice, to work in modes that are likely to be unfamiliar and uncomfortable, and to consider the different audiences and users who are the target of both speculative fiction and scholarly knowledge production. It begins with the two-factor pedagogical premise that (1) if students are to be fluent writers and makers, they must learn how to compose for a variety of media formats and lengths as the digital medium makes traditional writing styles increasingly obsolete; (2) as science fiction expands in the twenty-first century to become more visible (if not dominant) in new media across the cultural landscape, students must be fluent in how nonlinear, user-driven experiences on mobile devices, in video games, and interactive physical spaces are created and developed conceptually and technically, and how those processes shape the relevance and context of science fiction stories.

[4.4] This framework was drawn from the discourse on interactive technology and pedagogy and design thinking. Having studied and taught in the City University of New York Graduate Center's Interactive Technology and Pedagogy certificate program, I believe in an interdisciplinary, practice-based pedagogy that integrates theoretical, historical, philosophical, literary, and sociological knowledge resulting in praxis-oriented coursework, academic research, and scholarly publication ("Interactive Technology and Pedagogy Certificate Program," n.d.). This combination of teaching, learning, technology, and creativity is vital for contemporary education, not just because of the increase in digital technologies in the classroom but because, like in science fiction, it is important to understand how technologies and media implicitly and explicitly shape our understanding of texts, our communication with one another, and our relationship to the changes in society. In a class that leverages fandom as part of the learning experience, Katherine Anderson Howell notes, "We can invite [students] to participate in their education, to talk back to experts and authorities, and to shape the discourse themselves. We frame teaching and learning as actions, practices to be done, not lessons to be consumed" (2018, 6–7).

[4.5] The prototype assignment implements classroom practices that challenge orthodoxy in academia and generate creative, participatory affinity spaces for students. As such, the assignment encourages the students in liberating acts of cognition—à la Freire—where there is no right or wrong or facile transferal of information. Rather, the assignment necessitates the student's participation in fandom and assumes that the teacher is more likely than not to be less of an expert on the material than the student. In this environment, the role of the professor is to facilitate the understanding of an often unfamiliar creative practice of process rather than to presume or assert an intellectual superiority. Paul Booth (2018) notes how these kinds of assignments are particularly useful in courses that emphasize fandom as "the classroom moves from a space of membership (all are in the class because they signed up) to a space of interaction (students learn from one another and from their own experiences)" (122).

[4.6] To facilitate this approach to thinking and learning, students were introduced to design concepts and approaches to creating alternative experiences in a week titled "Interactivity," with Janet Murray's Inventing the Medium (2012) as a primary text. Few students came to the class having practiced thinking like a designer, but as our culture generally and science fiction specifically become imbued with more designed experiences, these skills are more relevant and important for passionate fans and more passive consumers alike. The best way to go about this has generated lively debate concerning the difference between a generalized design thinking as a way of approaching creative problem solving and a more formalized approach to design thinking used by design firms in corporate environments (Moggridge 2007, 2010; Brown 2008; Norman 2010, 2013, 2019). Tim Brown (2008), head of the famed design firm IDEO, calls for a cycle of Inspiration, Ideation, and Implementation. Others follow the five stages proposed by Stanford's d.school: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, Test (Dam and Teo 2019).

[4.7] No matter what the specifics, the core values transfer well to courses and classrooms looking to develop affinity spaces. As renowned designer Bill Moggridge has stated, "[Designers] learn by doing, assembling a rich and intuitive understanding of restraints, knowing how to create alternatives, developing representations and building prototypes, evaluating solutions and choosing directions, rejecting unsuccessful solutions and trying another cycle of the process" (2010, ¶ 3). The prototype assignment encouraged students to embrace these traits and processes from design and connect them to creative thought, experimentation, and knowledge production. The proposal connected their passions and research to an initial inspiration or idea. Then discussions with myself and classmates and midstage presentations moved along the process of prototyping, testing, getting feedback, and refining.

[4.8] Once this framework of interactivity, design, and knowledge production was laid out for the students, the cooperative participatory space of the seminar and the individual fannish impulses of each student created a fruitful cycle of inspiration, experimentation, and critique. The students were encouraged to pick a text that they really are a fan of or that they really feel challenged by so that this exhilaration of affinity could drive them through difficult moments in their process. It was not the length or canonicity that made the text they chose important but its relevance to how the students wanted to highlight what they are a fan of in the piece. As a group the students also acted as a test audience of critical fans. Through presentations of proposals, early drafts, and end-of-the-semester versions, the students had to make the case for their choices, describe what they found compelling, and convince the rest of the class to be fans of their work.

[4.9] During these critiques the students also came together as a creative unit—sharing advice, highlighting what was compelling, exciting, confusing, or off-putting, and brainstorming revisions, improvements, and innovative divergences from early plans. The students often worked together between presentations if they found affinities between their projects, and asides during weekly discussions or conversations during breaks often came back to exciting challenges and new ideas with which the students were grappling. The class soon became as generative and supportive a community as those that can be found on sites such as Archive of Our Own. Because graduate students are already versed in the complications of academia, they are capable, as Katharine Anderson Howell (2018) has noted, of finding "meaningful community that addresses both the practical academic need and the relational affinity need within the remix classroom" (6). This coming together of the group generated the authentic communication that Freire (2018) calls for in liberated education that is vital not only to the students' work in the classroom but to how that work connects to reality in the world beyond. As the semester progressed, the students found their projects dragging them further down fascinating rabbit holes as their scholarly minds combined with their fannish dedication to create more complex, more creative, and more detailed projects.

[4.10] Most importantly, students were constantly reminded that the end goal of the project was not a fully polished prototype ready to take to production. Rather, however far they could get in fifteen weeks was how far they would get. So long as they showed endeavor and commitment throughout the semester—which was often not difficult to motivate because their investment in fandom pushed them along—the project would be considered a success. The materials they handed in were considered a work in progress, a midpoint in what were almost always ambitious, aspirational projects. More often than not the projects were shockingly successful, as you will see in Fiona's work.

5. A prototype: A scare house

Fiona

[5.1] As emphasized by Ursula K. Le Guin, science fiction offers another way to describe reality (1980). In this course, the power of speculation allowed for the student to devise a prototype. The student prototypes behaved akin to the remixing or adaptation of a preexisting text (Schäfer 2012, 46). For my project, I converted a linear narrative into an immersive experience juxtaposed to fan engrossment over canonical material. As I proceeded with my project, "Enter the House of Pain," I grounded my work in the narrative of H. G. Wells's The Island of Doctor Moreau to transform science fiction literature into an interactive think-piece. This contextual, interdisciplinary approach reconfigured the text to develop a design process and to digitize the presentation through social media to foster audience engagement. Representations of the prototype exhibited attributes of explicit participation in which technology was subverted, or appropriated, with technical skills undergoing evolution or becoming a cause for improvement (Schäfer 2012, 52).

[5.2] To propel my tinkering, I compiled a critical study of H. G. Wells's The Island of Doctor Moreau for our class assignment, the second essay, which critiqued anthropological, historical approaches (note 2). On a remote island, relentless experimentation through vivisection pushes against scientific limitations; half-beast, half-human hybrids are created by the cruel hand of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist turned creator-god. In his evolutionary quest, Moreau aims to test "the extreme limit of plasticity in a living shape" to manipulate nineteenth-century notions of biology (Wells 2002, 102)—in the "House of Pain," Moreau's laboratory, agony celebrates evolutionary progress. Thus impacted by Darwinism, the Beast People possess "the accompanying fear of devolution (along with a growing mistrust of science itself)" (Graff 2001, 33). Civilization, unable to process tumultuous adaptation, thus unravels. Viscerally, the reader experiences the horrors of change through the viewpoint of the novel's narrator Edward Prendick; similarly, guests navigating my theoretical attraction are exposed to sudden, unexplainable atrocities.

[5.3] My case study presented a multimedia experience where fandom is experienced by an audience and fannish activities are embodied by performers reimagining H. G. Wells's The Island of Doctor Moreau as a twenty-first-century scare house. I identify a scare attraction (alternatively referred to as a scare house) as an attraction meant to simulate fright in an artificial, theatrical environment. In other words, the scare house offers an immersive experience postulating a relationship between the participants and the actors to elicit terror. The framework for this concept resembles the construction of fan fiction within fan spaces. In fact, this prototype mirrors a reconstruction of canonical material as made apparent in fan fiction (De Kosnik 2015, 1). In the realm of fan fiction, readers and writers "understand that they should create mental images of specific actors performing scenes that the fan author describes" (1). During the development process, I transcribed my theoretical scenes as a creative writing piece. The scare house environment became a fic-like riff on Wells's original work.

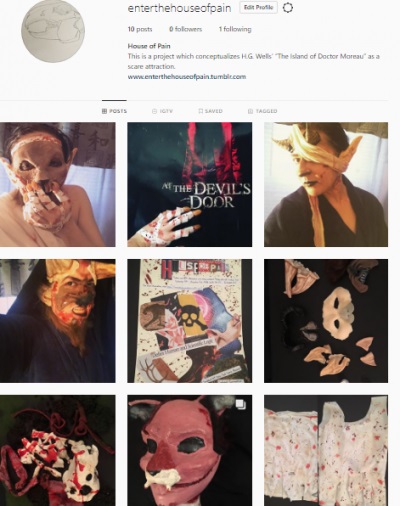

[5.4] By translating a two-dimensional text into a three-dimensional experience, the prototype synthesized research, secondary analysis, critical theory, and peer engagement. Designing such an experience engaged both my interest as a fan and promoted interaction among fellow fans, and during this process I employed an interactive narrative to depict a modern societal relationship immersed in "digital technology" (Brown, Barker, and Del Favero 2011, 213). Using the social media platforms of Twitter (figure 2) and Instagram (figure 3), I encouraged user interactivity through the perpetuation of artificial advertisements.

Figure 2. Screenshot of the House of Pain attraction's Twitter feed. The primary motivation was to promote social engagement (https://twitter.com/enterthehouseo1).

Figure 3. Screenshot of the House of Pain's Instagram page offering behind-the-scenes footage (https://www.instagram.com/enterthehouseofpain/).

[5.5] On one hand, the act of manipulating Instagram playfully and intentionally by curating a digital archive for the "House of Pain" calls to attention how fan labor has become exploited by corporations and companies alike. As Kristina Busse has commented on the capitalization of fan labor, the consumer is "rebranded as fans, and as fannish modes of sharing and spreading interest get rebranded as viral marketing, entire companies are dedicated solely to mimicking and replicating fannish passions as user-generated content" (2015, 112). In the example of my prototype, there exists a murky uncertainty over the use of social media as it either mirrors capitalized fan activities or recognizes these modes of engagement.

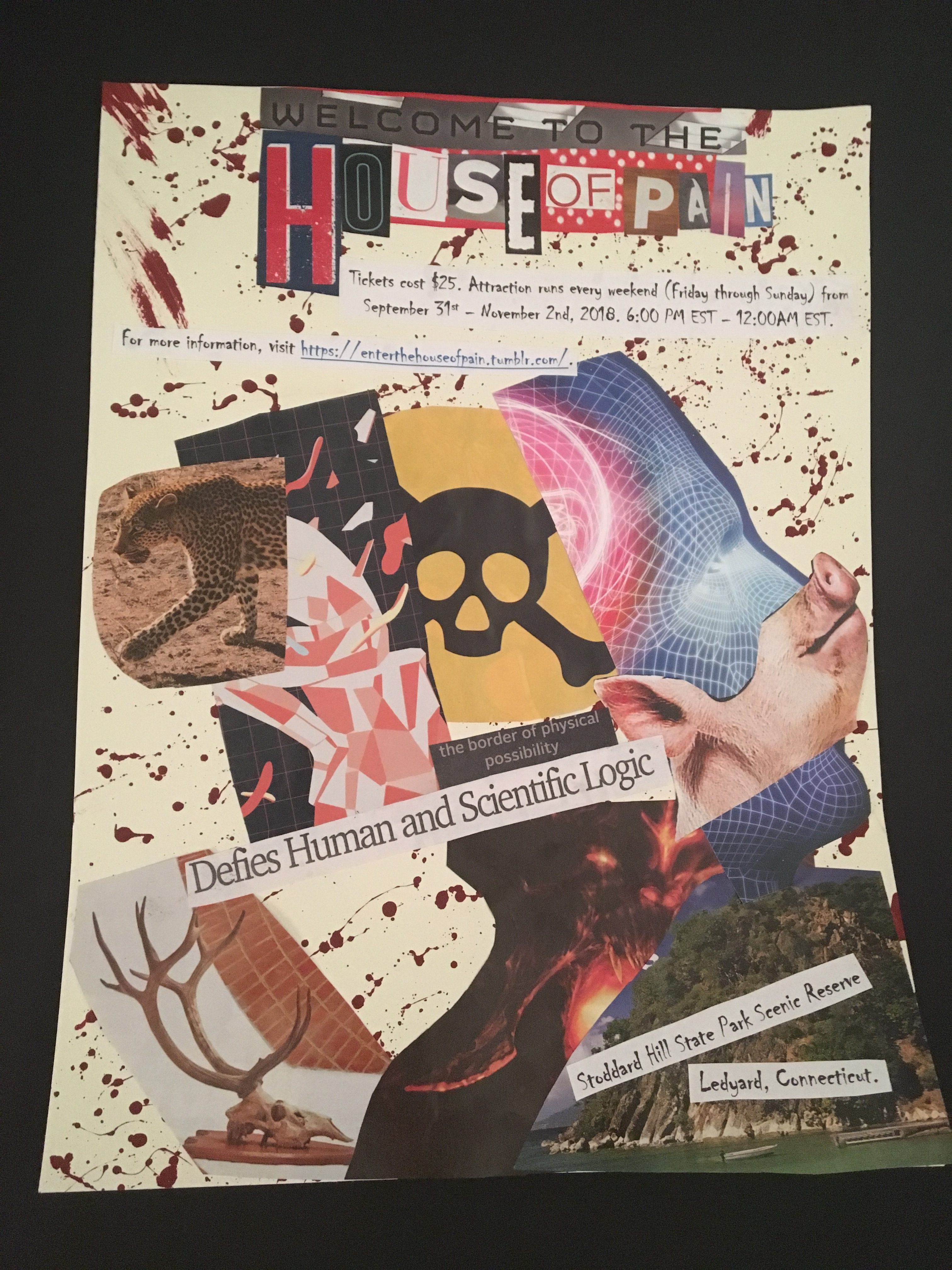

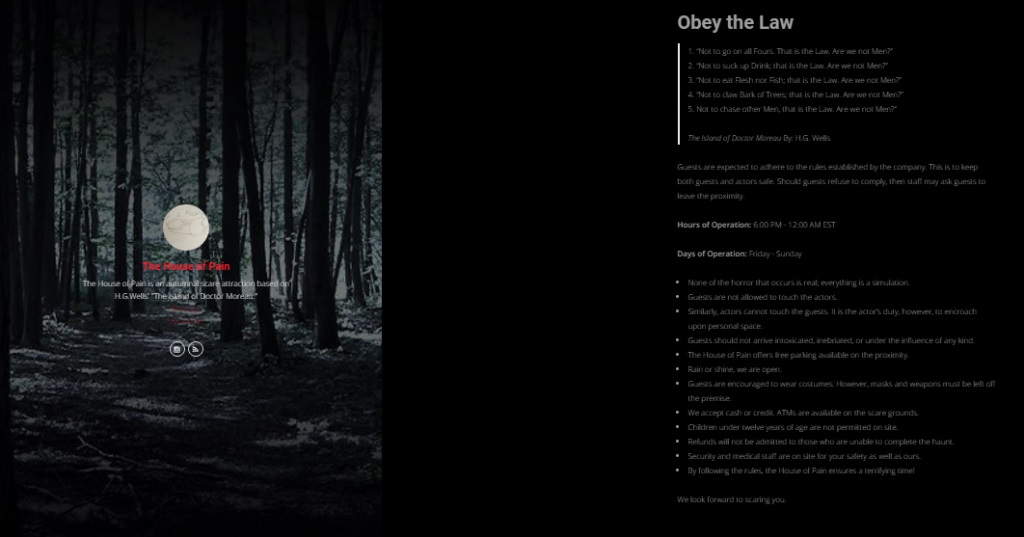

[5.6] On the other hand, participatory culture incorporates the technological into these representations and reworkings of media (Schäfer 2012, 52). Rooted in fandom practices, I implement a do-it-yourself (DIY) praxis by replicating aspects of a haunted house attraction. For the flyers I created (figure 4), mixed media art simulated information about a theoretical attraction. To complement this narrative, I used Instagram and Tumblr (figure 5) to simulate an artificial reality in an online space, which simultaneously functions as a future archive, similar to "online fan archives" which "offer visible evidence that audiences actively and imaginatively engage with media texts" (De Kosnik, 2015, 1). In line with Abigail De Kosnik's work on fan fiction, "fans appropriate the repertoires of bodily performances that they see on screens, and reenact those repertoires in different spaces" (2016, 247). These sites allude to a performative interaction with a virtual audience. The premise of a scare house invokes participatory culture structured as a type of performance where guests react to the interactions shared with the actors.

Figure 4. Conceptual flier design as promotional material for the House of Pain.

Figure 5. Screenshot of the House of Pain's website and the attraction's visitor rules, as depicted on a Tumblr blog (https://enterthehouseofpain.tumblr.com/).

[5.7] As an attraction, the House of Pain simulates civil unrest apropos to contemporary society's ails in the embodiment of sheer chaos. Promising a wicked fright, the House of Pain assumes a sensorial experience. Situated in an experience akin to immersive theater, the participants confront fears, anxieties, and tensions. Reminiscent of immersive theater, a scare house fuels a narrative where the spectator endures an illusionary experience to question interactions that might occur between "an artifact, system, or environment…and a human" (Janlert and Stolterman 2017, 113). In the circumstance of the House of Pain, interactivity occurs between the actors and their stage, the actors and the guests, the guests and the attraction, as well as the guests and social media. In the context of this scare attraction, audiences roam "meticulously-designed spaces, fully encompassed in the fictional world created for the performance" (Howson 2015, 115). Through participation, immersive theater encourages an audience to respond to senses and spaces; immersive theatres "address current societal concerns and the imposed 'fearful state' of 21st-century civilization" (122). Just as the H. G. Wells novel poses moral dilemmas pertinent to Doctor Moreau's mistreatment of his victims, my scare attraction questions what is ethical in regards to actor–audience interactions.

[5.8] Directed under the pretense of a linear narrative, my guests stroll along a trail while the story adapts in response to interactions with guests. Here, speculative fiction supports the prototype as a haunted attraction. Indeed, "the speculative nature of science fiction allows its writers to explore that which is not currently possible or is not aligned with current morality" (Clements 2015, 181). By granting participants freedom to interact, the experience is tailored as a personalized account. Analyzing immersive theatre experiences, scholar Olivia Turnbull notes that "one of the most familiar techniques employed in immersive theatre is to offer spectators agency" (2016, 153). In my theoretical scenario, the scare actors in the House of Pain construct a believable portrayal of the Beast People (figure 6).

Figure 6. Prosthetic mold hand sculpted out of clay, intended to depict the Sayer of the Law character in the H. G. Wells novel.

[5.9] Furthermore, dramaturgical theories interpret human action as performative: social life behaves akin to a theater or a theatrical experience (Hałas 1987, 23). Perhaps the guests interacting with my attraction would elicit a reactive performance to parallel this speculation. Immersive theaters engage with narratives to "offer a new way of encountering familiar plot lines through a first-hand sensory experience, where the space cannot only be seen but smelt, heard, felt and touched directly" (Howson 2015, 124). Although a scare attraction might provoke discomfort, relief follows thereafter. As a scare house, the immersive theater of the House of Pain promises a therapeutic catharsis, after the adrenaline rush.

[5.10] Propelled by passion, the labor of this project incorporates my emotions in an attempt to make "the work meaningful" (Deuze and Prenger 2019, 24). My appreciation for the DIY ethos allowed me to translate the proposal into a feasible prototype (figure 7 and figure 8). The DIY approach invokes a sort of affective play: "affective play 'creates culture' by forming a new 'tradition' or a set of biographical and historical resources which can be drawn on throughout fans' lives" (Hills 2002, 79). Driven to replicate a self-made attraction harnessing available resources, these handmade items encapsulate the crudeness often incorporated into low-budget horror attractions. I chose to reconfigure H. G. Wells's text due to the proverbial fan fiction that I had internally developed. I envisioned a malleable, three-dimensional space based on my previous encounters with scare attractions; this imaginative task echoed how "people have to make emotional maps of media in order to decide, of the overwhelming number of possible media performances presented to them, which ones they will consume and become involved with, which ones they will become fans of, which ones they will use as the bases of their own performances" (De Kosnik 2016, 278). For the development of this prototype, I embraced Wells to present an immersive landscape that not only testified to my engagement as a fan but pushed my critical thinking as a scholar by contextualizing the project's design with various theories.

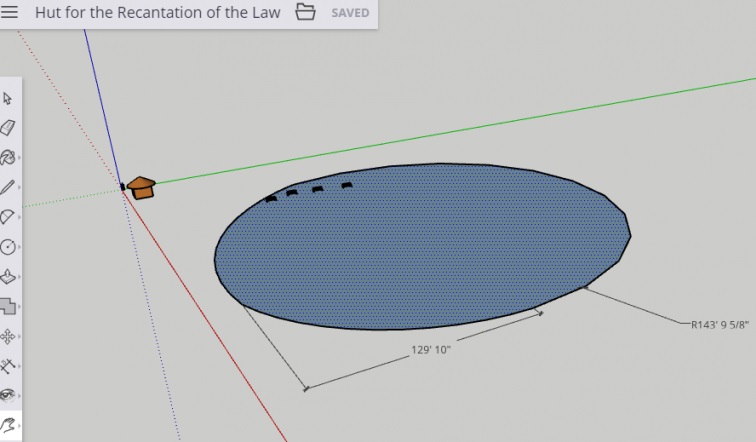

Figure 7. Screenshot of the student's attempt to render a three-dimensional model of one aspect of the House of Pain scare attraction via Sketch Up software. (Images are not to scale.)

Figure 8. Model of the scare attraction that emulates the House of Pain. An exterior view is shown of Moreau's home, which the student assembled and painted.

[5.11] In distinguishing fans from scholars, "the ideology of fandom involves both a commitment to some degree of conformity to the original program materials as well as a perceived right to evaluate the legitimacy of any of those materials, either by textual producers or by textual consumers" (Jenkins, Itō, and boyd 2015, 55). In the classroom, the solidarity often apparent within fan spaces became evident in the sources exchanged among my peers. My prototype did not seek to undermine the original text but rather sought to modify and redistribute The Island of Dr. Wells as a reinterpretation. The act of peer participation, in this instance, elicited empowerment by "adding greater diversity of perspective, and then recirculating it, feeding it back into the mainstream media" (Jenkins 2006a, 257). Feedback from other students gained me valuable connections to Cinema Secrets and Woochie FX that facilitated my progress. A fellow student's involvement with Frost Valley's Haunted House Events allowed me to interview staff on the experience of operating a scare trail. Thus, my prototype paints a picture of how fan consumption produces fan objects (Jenkins 2006b).

[5.12] Influenced by the work of my peers and the source texts, my final project produced a digitized, interactive presentation to detail the design process. At the crossroads between science fiction and horror, I relied on a contemporary context to shape the project as an immersive experience. I sought to produce an artificial "designed experience" in which I would "structure an environment to create affordances for a human participant" (Heeter 2000, 7).

Kimon

[5.13] Usually, when I create a new course or new kind of assignment, I think I have a good grip on the range of projects I will receive, the quality of those projects, and the kinds of nonlinear experiences the students will devise. But the work that students produce in SF: HTPF never ceases to amaze me. Here is a list of some standout projects:

- [5.14] A tabletop role-playing game based on The Twilight Zone TV series that has players make moral decisions based on minimal knowledge of a given situation.

- An exhibition based on a Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode known for its challenging take on ethical decisions where user choice can change the ending.

- A choose-your-own-adventure style rewriting of Kafka's Metamorphosis.

- A series of Twitter bots that represent the early X-Men team and respond to tweets in ways that reveal the gender and sexuality biases present in 1960s comics.

- A text-based adventure version of Rick and Morty that eschews graphic richness to focus on parallel universe exploration and understanding the show's theoretical physics.

[5.15] Even with all these projects, I had never thought of something on the scale of a scare house as a possibility, and Fiona's choice and execution went beyond all expectations. The quality, expansiveness, and thoughtfulness of her prototype was a testament to the power of a commitment to fandom to act as a motivator for exceptional work. In fact, students often tell me that they spend far more time on this assignment than those in other classes, but they rarely notice or resent the extra effort—rather, they enjoy it as fans of their own work. That is music to a professor's ears.

6. Conclusion

Together

[6.1] In the quest for meaning-making within society, we are always seeking to "expand our ability to understand the world and to connect with one another" (Murray 2012, 2). "Science Fiction: Humanity, Technology, the Present, the Future" encourages students to make meaning by analyzing and reconfiguring texts with the enthusiasm and rigor of a fan. This engagement proves to be an invaluable learning and teaching tool as professor and student alike embark on a cultural exchange of thoughts, theories, beliefs, and ideas. Through the development of an elaborate participatory thinkspace that encourages dialogical communication and cooperative learning, the course combines the most aspirational goals of progressive education and fandom. In this environment, the passion of fandom becomes a powerful motivator and a source of encouragement for students, whether they are leading the GotW assignment or working on the prototype project.

[6.2] As a result of their shared investment in the fandom that is the foundation of the course, both instructor and pupil become more deeply immersed in the content and contexts of the course materials. As the participants' experiences, preferences, and passions enrich the class, they encounter a wider array of methodologies and fandoms than the interests of one or two professors could possibly provide. This rooting of the course in a diverse range of science fiction expressions that are closely related to vibrant fans and fan communities develops an affinity space and "a participatory learning environment…that respects and values the contributions of each participant, whether teacher, student, or someone from the outside community" (Jenkins, Itō, and boyd 2015, 95). It further strengthens the argument that science fiction has an important role to play in describing our culture and society and enhancing our capacity to question and investigate the present. Through the course, all involved can walk away with a richer understanding of ourselves, our peers, our passions, and our world.

7. Acknowledgements

[7.1] We would like to acknowledge Robin Nagle for all her work and inspiration helping to shape and teach the first iteration of this course, and the faculty and staff of XE: Experimental Humanities and Social Engagement at NYU for their continued support. We would also like to thank all the students from the first three iterations of the course (fall of 2016, fall of 2018, and spring of 2020) who fully embraced the fannish aspects of the syllabus and assignments and helped it evolve from year to year: Austin Anderson, Zemí Yukiyu Atabey, Lina Barkawi, Madison Blecki, Bryan Bove, Hongyuan (James) Dai, Matthew Dischner, Jane B. Excell, Joseph Figliolia, Francis Ge, Andrew Harding, Brendan L Heldenfels, Dawn Howard, Yilang (Kisum) Jiang, Wei Kang, Arline Lee, Jessica MacFarlane, Ivan Martinez Autin, Johnathan McCauley, Alexandra McIe, Dylan Miller, Sophie Mishara, Sharon Onga, Samantha Paul, Charlie Peterson, John J. Petinos, Nathaniel Savoy, Valeria Seminario, Stacy D. Shirk, Nick Silcox, Colleigh Stein, Alex Sullivan, Daniel Torres, Sigrid von Wendel, Sarah Jane Weill, Quan Zhang, Mengjia (Jun) Zhao.