1. Introduction

[1.1] There has been a long-standing practice for fan fiction authors to receive help or ask for assistance from others with their fiction, whether they need assistance with plot development, characterization, background information about the fandom, or a simple grammar and spelling review. Assistance is provided through a system called beta reading. Betas, or "experts in writing [narratives,] guide, scaffold, and advise budding writers on their drafts" (Thomas 2008, 679) and provide "some of the best writing instruction [to take] place outside the classroom and in online communities" (Jenkins 2004). However, betas are not the only reviewers of fan fiction. Readers also regularly comment on stories' plot, content, and writing style. More, the comment section on a fic can provide new insight into the writing process that readers may not get in formal education. The long-standing link between fan fiction and learning about writing, coupled with the increasing mainstreamness of the genre, has afforded fan scholars the ability to ask questions about how fan fiction and fandom may be useful in the classroom as a tool to better prepare writers for either future careers or improved writing for pleasure. Rebecca Black's Adolescents in Online Fan Fiction (2008) argues that writing fan fiction inside and outside the classroom develops students' creative writing skills and communicative practices as well as providing social support that they might not have received in traditional classrooms. Additionally, Katherine Anderson Howell (2018) notes that inserting fan fiction and its practices into traditional classrooms would "offer students literacy and value in the class work, as well as citizenship" (120).

[1.2] However, the link between traditional education content and its use in fannish contexts is underexplored. In order to better understand this link, I completed a case study with fan fiction author Ruby and her recently published fan fiction. In addition to interviewing Ruby, I used a web scraping tool to pull comments from the stories that Ruby wrote; the tool isolated the comments from the rest of the text. After collecting comments on the story and investigating the correlation between lessons learned from the classroom and in online fandom, I used computational techniques to look at word frequency and use. Results indicate that fic writers and commenters engage in structured, formal analysis of texts, performing close readings that rely on modes of discourse clearly influenced by formally taught English literature classrooms.

[1.3] Here, I take a closer look at Ruby's work and the comments left on her fic. I will first address the ways that I selected participants for my study and explain why Ruby was selected in particular for this research (note 1). I will then provide a background on Ruby, her fandom, and her work, all of which was taken from an interview with Ruby. The interview provides a close examination of Ruby's writing and production style and also provides insight into the ways that she interacts with her readers in the comment section. Next, I will break down the documentary analysis that I completed on the comments on Ruby's work. The scraping and data visualizations provide an in-depth look at the ways that readers interpret a work by analyzing the words that they choose. In order to complete the documentary analysis, I used a Python tool to scrape the comments from the website and pull them into a CSV file, on which I used three main pathways of analysis in RStudio (https://rstudio.com/) through the natural language process: data visualizations (including word clouds and bar graphs showing word frequency and used to determine what terms fans used the most in relation to Ruby's work); term association (showing the frequency with which words occur in correlation with other words and used to determine if people discussed topics like "reading," "learning," or "writing"); and topic modeling (showing related terms used for words and allowing an examination of the underlying semantic structures of the comments). This reveals how readers use the literary analysis, figurative language, and close reading skills (often taught in secondary English literature classrooms) in their comments on fan works. The data and analysis demonstrate that fans use skills learned in the traditional language arts classroom, like performing close readings or understanding figurative language, in their comments on fan fiction, which furthers the argument for the inclusion of fic when considering pedagogical approaches to teaching literacy.

2. Participants and methods

[2.1] The DePaul institutional review board (IRB) approved this study on March 18, 2019. The study was submitted as an expedited review. In order to complete the case study, I selected writers via an informal message on a public subreddit, identifying the purpose for the study and details of the study. When participants responded to this subreddit (whether in the thread or in direct messages), they received a link to a survey on SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com/) with an altered short consent document that asked for their agreement to be screened for the study. In the survey, participants were allowed to view the consent document and tick yes or no for their consent. The survey also asked for their reddit username to keep track of the participants who consented.

[2.2] After receiving consent, as well as the Tumblr and fan fiction website URLs, I used the eligibility criteria to determine whether the writers fit the parameters of the survey. Some participants may have responded and not fit all the criteria, so this prescreening acted as a double check for particpants that fit all the criteria. Tumblr gave me insight on how the participants interacted with followers and fans of their works. The fan fiction URLs gave me insight into how past works have incorporated multimedia, as well as interactions with fans, betas, and other writers. The selected participants fit all of the eligibility criteria.

[2.3] After this informal recruitment process, and after determining which participants fit the study parameters, I connected with the participants via reddit again. I let the participants know that they had been accepted, and I asked for their email addresses to provide the participants with the voluntary consent agreement forms. After receiving consent, I sent the participants a Google survey (through the email obtained on reddit) to collect demographics (age, pronoun preferences, gender, time zone, fandom, and education level). The obtained responses resided in an encrypted folder on my computer and linked the survey results to a code name. Each encrypted file also held participant interview documents, consent documents, and any other materials related to that code name/participant.

[2.4] Participants were selected from the subreddit /r/fanfiction (https://reddit.com/r/FanFiction). I selected this social media platform because /r/fanfiction is not sequestered into fandoms. This means that gaining access to many fan communities at once is possible. The subreddit describes itself as "a supportive community for writers, readers, and reccers to talk about and share FanFiction" and has roughly 47,000 members. I posted a "call for fan fiction" on the subreddit, asking for fan authors to submit multichapter fics that had a beta and were ongoing. Participants responded to the call, sending me their fan fiction via the thread. This post was the top post on the subreddit for the first twenty-four hours that it was posted and received over 150 responses; however, the cyclical nature of Reddit—that is, the prioritizing of recent threads over older ones on the website—may have limited the number of responses to the call.

[2.5] I had several criteria for my participants. First, I asked that the author have a beta reader because, like a peer reviewer, betas provide feedback on content, form, and style. Betas' understandings of what is required may differ greatly from writers' understandings. Fics that have been read by betas thus provide important insight into how the common pedagogical practice of peer review is and is not mirrored in fan practice. Betas may act in many roles in producing fic. They often line edit and make changes to grammar or mechanics, but some may also workshop the fic with a writer. They may suggest that the plot be altered or that a characterization be changed to reflect canon (i.e., the source text) or fanon (i.e., the generally accepted characterization within the fandom). Additionally, betas may help authors keep their audiences' needs in mind; for example, they may interject when they believe more information is needed for the story to be cohesive or coherent. Finally, betas provide meaningful formative feedback, something that peer review or workshops in formal educational contexts also achieve (Li et al. 2020; Liu and Carless 2006).

[2.6] I chose to study writers with new multichapter fics because doing so would allow me insight into real-time interactions. A work in progress (WIP) fic was extremely beneficial because, as the name suggests, WIPs are not published all at once but instead over days, weeks, or months. Using WIPs meant that I would be able to observe the authors' interactions with their betas and readers across the whole work instead of being constrained to a small set of comments on a single chapter. Moreover, multichaptered fics necessitate more interaction about the work over a longer period of time, which makes developments in the writers' processes more apparent; they therefore provide a more robust source of data. For example, in Ruby's work, after she posted each chapter, its comments often discussed how the chapter fit into the overall plot, which of the readers' wishes had come true, and what cliffhangers or plot points could guide the reader to hypothesize about what might happen next. These kinds of discussions would not happen on a fic with only one chapter.

[2.7] I requested the participation of authors whose fic was posted to either Archive of Our Own (AO3) (https://archiveofourown.org/) or FanFiction.net (https://www.fanfiction.net/), as these two websites reach the largest fan populations. As such, fics posted to these sites likely garner numerous comments from a wide fan demographic. Because comments comprised part of my data, I also wanted to interview authors who had active reader and writer interactions in the comments sections on AO3, FanFiction.net, or social media. These interactions form the basis of a following for a story and allow in-depth conversations about a work to develop. For example, the readers Ruby interacts with daily on the Discord social media platform (note 2), who often help her workshop her fics, comment on her story when it is posted, noting the changes she has made on the basis of their suggestions or continuing the conversations from Discord. Participating fan fiction authors were asked to undertake video chats with me at least once every two weeks, so that I could discuss the comments and the act of fic writing with them over time and observe their habits in detail.

[2.8] As I combed through the URLs provided by authors in response to my Reddit post, I began to segment the data. I looked for metadiscourse in the comments, places where readers and the author substantially responded to the fic and talked about the literary and stylistic elements of the fic. I also looked for fics that had multiple comments and author responses, demonstrating ongoing conversations between the authors and their readers about the works. I began to see places where readers created their own spheres of intertextuality and intratextuality. For example, readers may bring connections of "text-between another text" as well as "ideas, notions, thoughts, and experiences that shape their understanding of the narrative" to the comments section (Booth 2010, 55–56). In their comments on Ruby's work, for example, readers often relied on their knowledge of the fanon or canon of her source text, Supernatural (2005–20), as well as their own ideas about the world of Supernatural and their own experiences when giving feedback. One reader wrote, "I totally relate, though. TFW you're on a work trip and have to switch from 'work is paying for this' to 'work is not' mode for dinner" (note 3). Additionally, Ruby's work was an alternate universe (AU) fic, which meant that readers were able to analyze her use of the other text that she referenced (another television show) and to make intertextual connections. Intratextual connections that readers draw between the chapters in the fic propel "the reader deeper into a media object, as it connects aspects of the text to other aspects of that text" (Booth 2010, 56). For example, in the fic I studied, Ruby writes, "She was pretty, with dark brown hair gathered in a functional bun and large black eyes. She winked at him before walking away." In a comment about this section, a reader speculates on the importance of that scene and its relation to the overall story, stating, "Imma remember her, she's probably important." This section shows that the reader perceives Ruby to be using foreshadowing, which encourages them to remember specific details of the text and to develop intratextual connections.

3. Case study: Ruby

[3.1] In her interview, Ruby noted that she was thirteen when she found fandom. Her first fandom was Sailor Moon (1992–97), and she currently writes in the Supernatural fandom. A native French speaker, she has recently started reading and writing in English, and fandom has allowed her to consider her personal identity, discuss sexuality and sex, and develop friendships with people outside of her immediate social circles. Upon her entry into fandom, she interacted with other fans through play by post, a combination of online role-playing and creative writing (Ito et al. 2009). In play by post, users create threads on social media (such as Twitter), with each post adding a sentence or character to an unfolding story. Ruby moved through fandom in this way throughout her teenage years, investing time in role-playing games and collaborative writing in chat rooms. At the time this study was undertaken, Ruby most often wrote drabbles, which are very short fics, totaling only about 100 words (note 4). She also wrote longer fics reaching about 30,000 words in length. All of her stories have been edited by the same beta reader for the past two years. She workshops them first on a Discord channel, with drafts written in Google Docs so her beta reader can view them. She posts completed fiction on an archive site, then engages with readers via the chapter's comments or via the relevant Discord site or other social media channels.

[3.2] Ruby stated that she tried to be as responsive as possible to her stories' comments: "I answer every single comment; I am a literal human puppy when I get them—so very excited and eager to comment back." She says that her comments depend on the relationship that she has with the commenter. If she does not recognize the username from previous comments or Discord, she generally simply thanks them for reading her fic—the default response of many fan writers. If the commenter is someone she interacts with frequently, the answer tends to be more personalized. She says that overall, about 70 percent of the comments on every story she writes are detailed, which she feels makes her lucky, as many authors receive shorter, less detailed comments. She says that Discord (where she acts as a moderator) draws out a lot of these more detailed comments, as she has usually workshopped her piece there, and many of the comments reference what the reader and Ruby have talked about. Ruby values "the communities [that are] created within the servers: it gets a lot of people to read outside of their fandoms. People are like, 'Maybe I'll go read this because someone posted it and it seems interesting.'"

4. Documentary analysis

[4.1] After interviewing Ruby, I analyzed her stories and their comments using documentary analysis, "a form of qualitative research in which documents are interpreted by the researcher to give voice and meaning" (Bowen 2009, 29). I began by looking at all of the texts Ruby had produced, noting the target audiences of each, the tone that she used, the story's purpose, and the style in which it was presented. After I had asked these questions of the texts, I examined them and their related comments closely, looking for figurative language use (symbolism, imagery, personification), examining the narratology (the narrative choices made by the author and structures of the text), and considering the contextual world building (how the author uses the setting of the story to discuss and study people and cultures within the source text). I determined what Bowen (2009) terms "what is being searched for"—that is, precisely which elements I wanted to use as data in my analysis of learning skills. I then documented and organized "the frequency and number of occurrences within the document" by using a spreadsheet to tally the number of times elements of figurative language, narratology, or ethnography (as defined above) were used (35). I developed posteriori codes through my initial close reading as they were "related to central questions of the research," then collected and organized data from the story by using these codes (35).

[4.2] In my documentary analysis of the comments, I particularly noted reader comments like, "This helped me visualize x better," or "I understand this better because of y." For example, one comment on Ruby's work reads, "I think those last two paragraphs are what really starts this off. It puts the setting in place properly and shows us what's at stake for Sam and Dean." This comment helps broadly demonstrate a kind of norm for the work that many other readers follow in their own analysis of the text. In the full comment, the reader began by copying and pasting text from Ruby's work in order to clearly indicate which section they were going to address in their comment. The reader then analyzed that section, noting the setting and how it helps develop the plot points of the story. This process is reflective of how close reading is taught in English literature classrooms: students are first taught to cite the relevant passage that will be analyzed, then apply figurative language or other technical forms of literature analysis to the passage. Similarly, the basics of close reading as shown here parallel the norms put forth by writers of fan fiction for what Ruby termed "good comments." Comments that engage with specific details of the text and ask questions provide a rich opportunity for textual analysis, where authors and readers alike can delve into the world created and developed deploying strategies used in various literacies.

[4.3] A common topic in comments was Ruby's use of imagery. The translation of imagery into writing is always a game of chance, especially in fan fiction, where readers understand what the characters and settings of the source text—in this case, Supernatural—look like but may not be as familiar with other, added material. For example, if an AU takes place in an American city, readers from any other country may have a hard time picturing a scene unless it is carefully described. Ruby uses fan art as a paratext—the material surrounding a text that is not a part of the main body of the text—to help guide her readers. Fan art as paratext is either embedded in the middle of her fan fiction or is placed at the beginning. In one chapter, she embedded the art after a paragraph of description:

[4.4] Dean could feel the rise of Castiel's magic before he saw it…It had been night outside, but now light streamed through the kitchen window, the stark white of burning magnesium or lighting strikes. It cast strange shadows across the room, fractioned by the coloured glass baubles, making Dean's eyes water as he turned away, focusing on the large shadow wings that unfurled from Cas' back.

[4.5] In the comments on this chapter, several people mention how beautiful the included fan art was and how it complemented Ruby's descriptive imagery. One reader goes through the chapter, copying about fifteen lines from the text and discussing these lines at length in their comment. The commenter mentions the imagery that Ruby uses three times, synthesizing their discussion with a note regarding Ruby's world building. The commenter writes, "You are really good at throwing in tiny details that show a LOT. And then the exchange between Sam and Cas. I don't have to guess, and I don't have to read a lot to understand how much history is there." This commentary on the chapter is a "reflection of the reader's response that is intended for the author but does not necessarily include specific suggestions for improvement" (Reagle 2015, 45). It shows that the reader read the chapter closely, recognized the literary techniques and figurative language that Ruby used successfully, and provided feedback indicating to the author that they understand subtext.

5. Textual analysis

[5.1] After completing this qualitative analysis, I undertook a quantitative textual analysis, examining one of Ruby's past works: the prequel to the fan fiction examined above. Because her current work was in the process of being written at the time of the study, the prequel was better suited to quantitative analysis, and it had the benefit of being set in the same world. To scrape comments, I used R (https://www.r-project.org/) and its (rvest) library, which allows HTML and XML page manipulation, as well as the RSelenium library (Wickham 2020). A Python library for scraping fan fiction content and metadata already existed on GitHub (https://github.com/radiolarian); I modified the script so that the program would only scrape comments from the web pages comprising Ruby's prequel, thereby providing me with the prequel's data set.

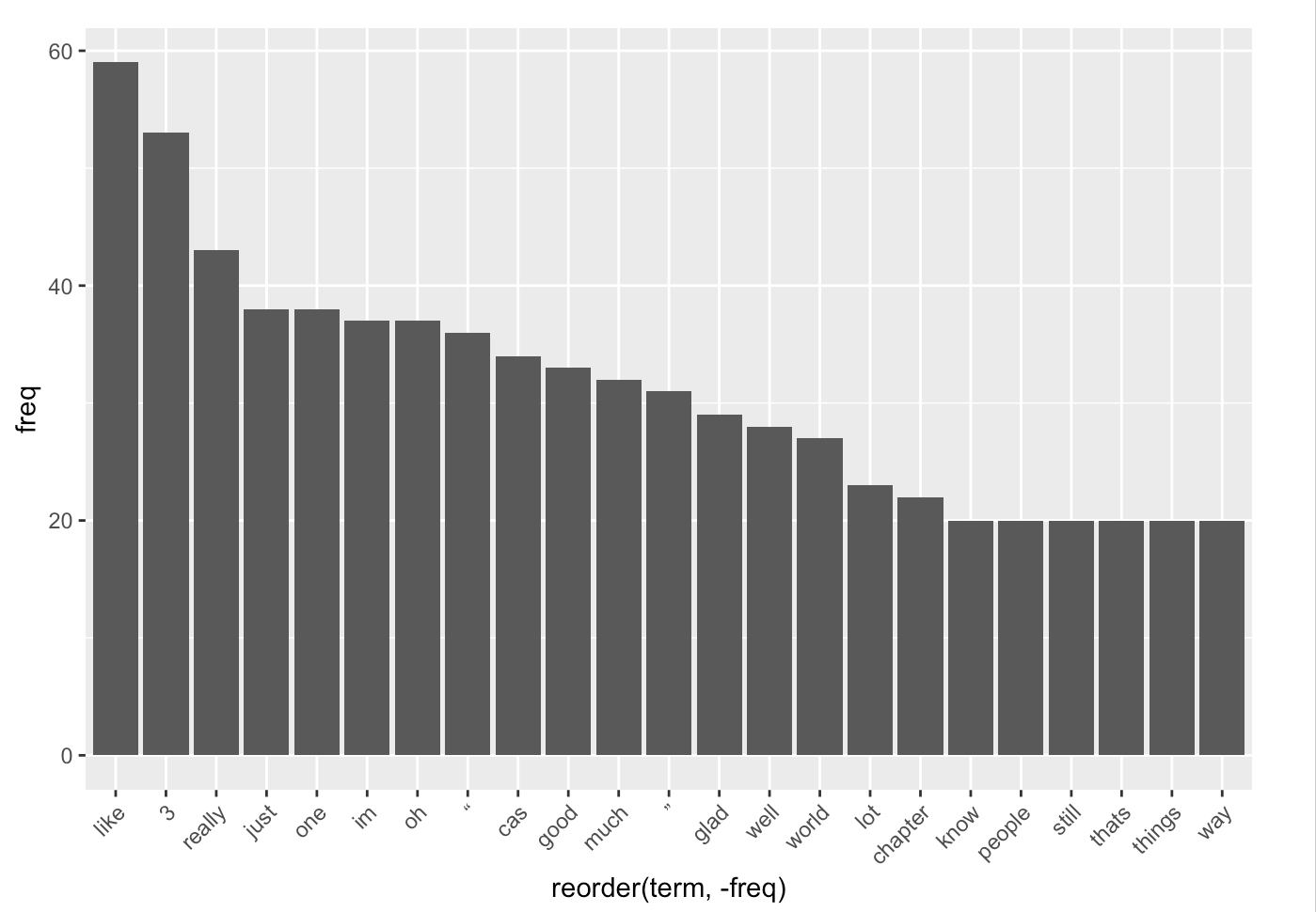

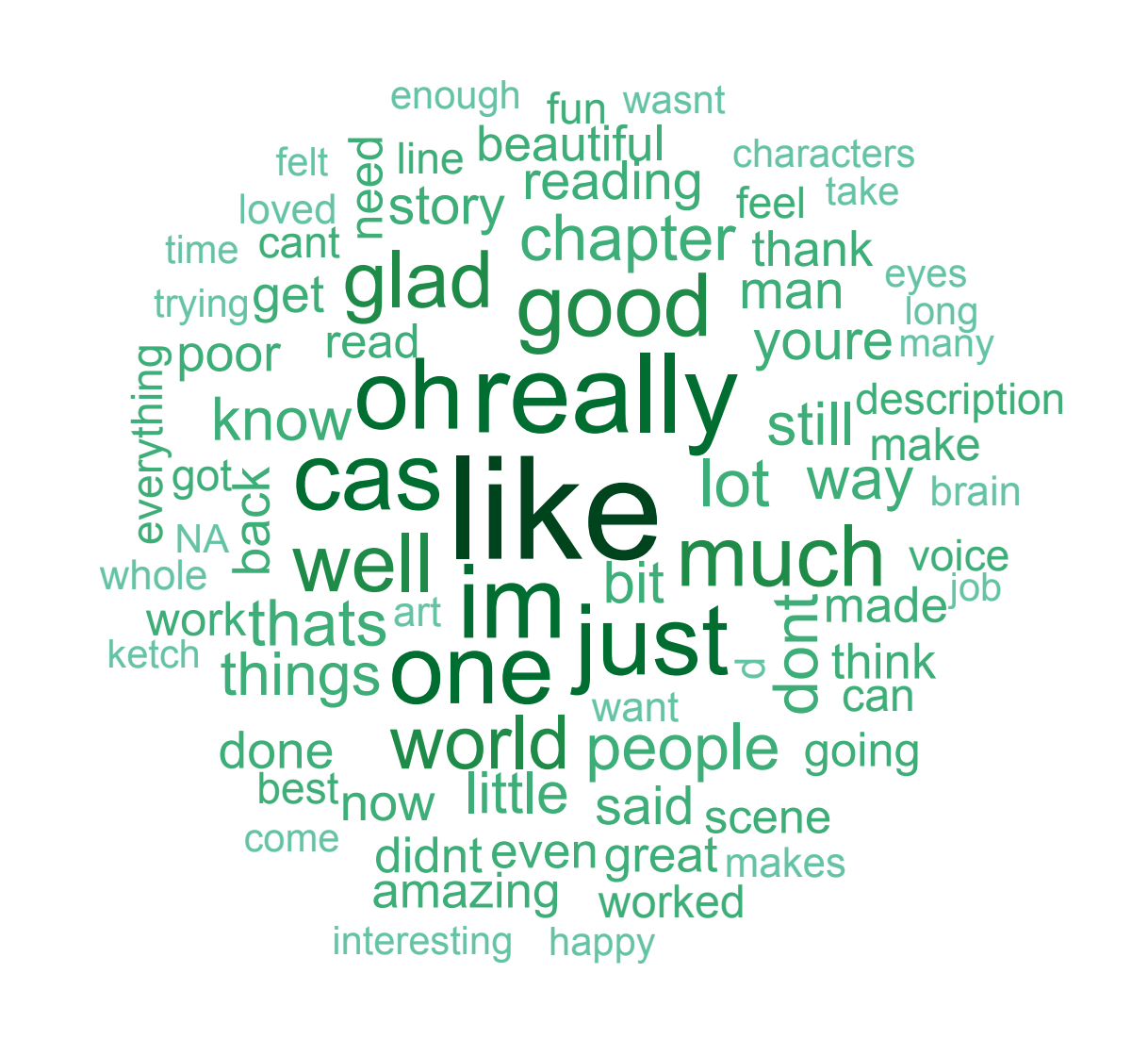

[5.2] After the initial web scrape of the comments, I analyzed the data. I first visualized the data using the R libraries (wordcloud) and (topicmodels) for text analysis. The (wordcloud) library allowed me to group the most frequently occurring words in the data and present these groupings visually, while the (topicmodels) library allowed me to group the data visually by topic. Having familiarized myself with the comments, I proceeded to create a customized stop word list that would be used in addition to the default library stop word list. Stop word removal permits researchers to filter out common words that are not distinctive and that may overwhelm text analysis at scale; my stop words included references to character names and certain abbreviations. Some of the stop words that I included were names of the characters from the source text (Sam and Dean Winchester, Castiel, Ketch); variations of "thanks," because gratitude is expressed so frequently in comments; and punctuation and white space. I did not eliminate URLs because I thought that they could usefully point to other platforms, resources, or links. I was interested in establishing which terms were used frequently within the comments. I looked more closely at subsets of words that appeared twenty times or more. This subset was then visualized in a bar graph (figure 1) and in a word cloud (figure 2).

Figure 1. Bar graph representing Ruby's comments.

Figure 2. Word cloud representing Ruby's comments.

[5.3] When I looked at figure 1, I noticed several things. The first was the frequency of the word "like." It is used over sixty times in the comments, but it was used in various ways. The data show that "like" was used twenty-four times as a verb expressing approval or pleasure ("I like this"), twenty-one times in citing the content of the story ("this was likely to come back and bite him later"), fourteen times to compare ("this world feels very SPN-like"), and four times colloquially ("Like things are crap, but we are like ok?"). I was most interested in the use of "like" as a comparison word. Focusing on these uses, I found that readers compared characters to other characters, to their own actions, to the television show, and to the world at large. These connections (often referred to as "text to text," "text to self," and "text to world") are commonly used by teachers and professors when teaching analytical and close reading (Kardash 2004). For example, one reader makes a text-to-text connection between the work and the world of Supernatural, as well as connections between the work and other AU fan fiction:

[5.4] Okay so I don't know Shadowrun and I don't read a lot of AUs like this, but they sound in-character enough and the world interesting enough that I think I'll like it…HOWEVER, this world feels very SPN-like if that makes any sense?…Anyway, it was riveting, and I was actually annoyed when my brother came home and wanted to talk so I had to take a break from reading. Can't wait to see more. Also, that cover art is AMAZING

[5.5] The use of "like" in this comment acts as a form of mixture description, or "descriptions of target documents defined by their likeness to mixtures of other documents," according to Organisciak and Twidale (2015, 2). These descriptions often inform the author of readers' connections between the original text, the transformed text, and further texts. For Ruby's work, these mixture descriptions happen frequently in the comments, showing the expanded frame of reference from fans in this fandom. For example, another reader stated:

[5.6] OH. MY. GODS. WTF JUST HAPPENED??! THAT WAS FASNIATING!! Okay girl calm down for a minute breathe for sec. The imagery of the caretaker walking into pool of blood and leaving red footprints everywhere was very unnerving. Poor lady! Glad they rescued the people that were snatched. Are they all like assassinations or is it more a programmable thing like on Dollhouse? I can't wait to find out aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

[5.7] Here, the reader makes a connection to Dollhouse (2009–10), another sci-fi show. These connections help develop readers' own intertextual understandings of a work; they also make these networks of meaning clear to the author and other readers.

[5.8] These conclusions drawn on the word "like" were completed in the first round of data analysis. I then removed "like" from subsequent analysis, changing the term frequency to determine its impact on the data set overall. However, words that connote mixture descriptions and textual connections were still present. For example, "world" was a frequent term used to acknowledge Ruby's world-building skills, which relate to the comments regarding mixture descriptions. For example, one reader comments on Ruby's world-building skills, then asks a question about Shadowrun (1989–) RPG fandom:

[5.9] I do gotta ask, since I'm a fandom-blind for Shadowrunner, why is Sam wearing a surgical mask but no one else is mentioned? Is it a personal thing, that some people who are more bothered by pollution/more germ freaks do? Or do people who get the computer-hacking stuff in their brain more sickly and more affected by the pollution.

[5.10] This reader makes text-to-text connections ("computer-hacking stuff in their brain more sickly and more affected by the pollution"), as well as a text-to-world or community connection ("Is it a personal thing, that some people who are more bothered by pollution/more germ freaks do"). The reader brings in their wider experiences with fandom, world building, and their own society into the comment. Similarly, another reader makes a comment regarding mixture description, stating, "I see you there, quoting Neuromancer! And I fucking love you for it because it's SUCH a great sentence." Neuromancer, a 1984 science fiction novel by William Gibson, follows the story of a computer hacker up against artificial intelligence, very much like Sam's character in Ruby's story and the characters in the Shadowrun role-playing game.

6. Associated terms

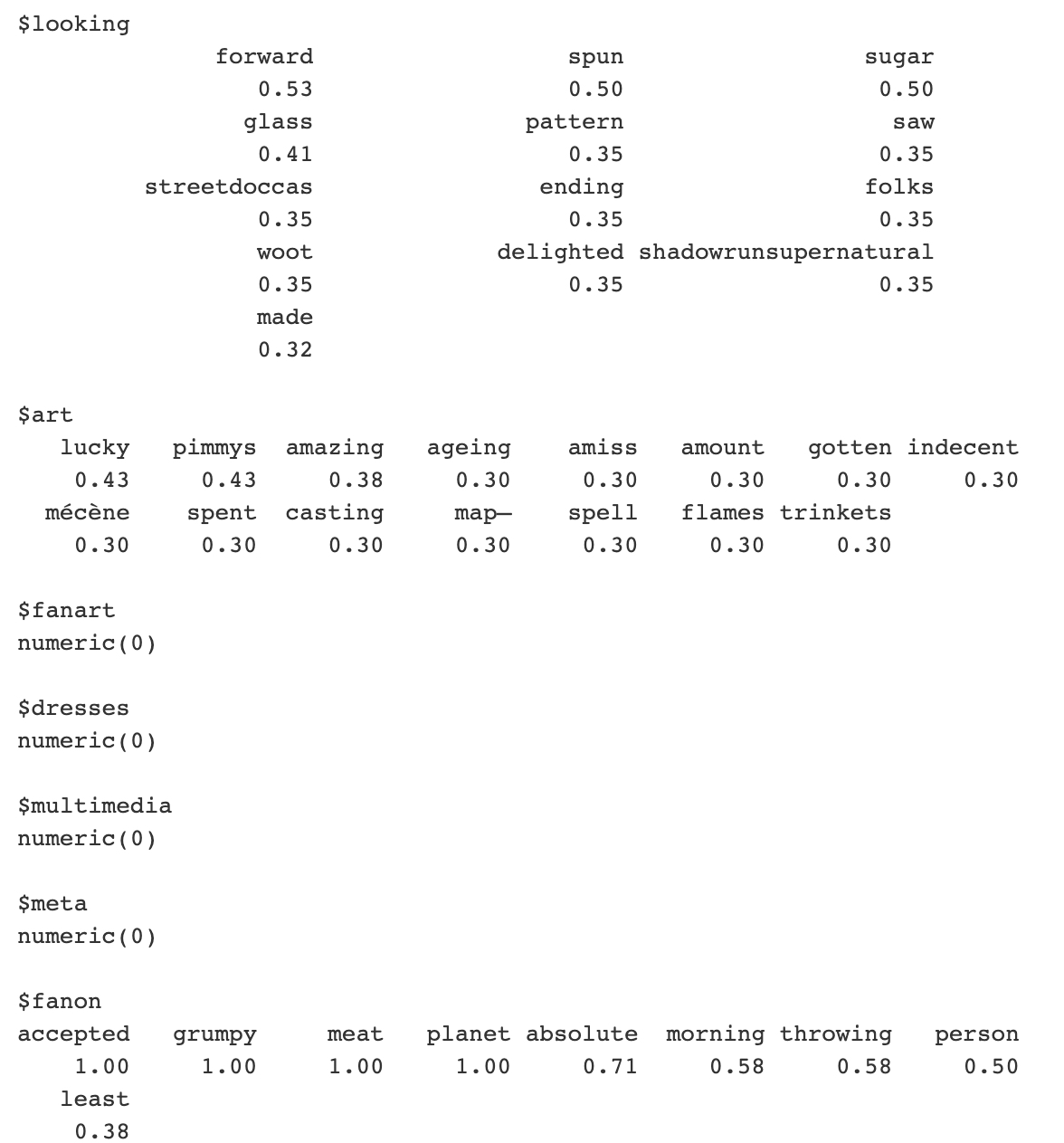

[6.1] I next created a term document two-dimensional matrix, which included individual terms in rows and documents in columns. Using the findAssocs() function from the (tm) library, I identified terms that were associated with my terms of interest, which were developed out of a list of words that I associated with learning (e.g., "studying," "searching," "understanding") and searched for terms that frequently appeared together in the document, setting the sensitivity to terms that appeared together at least 30 percent of the time, as higher correlation settings did not produce many results. One of the words I was interested in examining more closely through this matrix was "looking," because it was often used in comments discussing textual connections. A reader might say, "I was looking for a fic like this because of another fic!" Inputting this word into the matrix searched the comments for other words that occurred along with "looking." In Ruby's fic, some other words that were associated with "looking" were "glass," "ending," "delighted," and "sugar." This gave me an idea for other possible words that would be associated with the word I was analyzing, which could show relationships between the text and possible analytic skills. For example, one comment that had all of "sugar," "glass," and "looking" was a comment performing a close textual analysis:

[6.2] "Castiel looked at him for a long moment, not meeting his eye, just looking at him in that way that made Dean feel like he was made of glass and spun sugar. 'I'll need a personal item of hers,' he said, voice low in what sounded like a surrender.'" That is a beautiful metaphor and a really lovely way to end the chapter.

[6.3] The commenter notes that there is a metaphor embedded in the text. The scene before this actually sets up an extended metaphor that culminates with the words "voice low in what sounded like a surrender." The recognition of this as a "beautiful metaphor" and the nod to an extended metaphor shows that the reader is using modes of analysis likely to have been taught in a literature classroom.

Figure 3. A termAssoc() of the word "looking" from Ruby's comments.

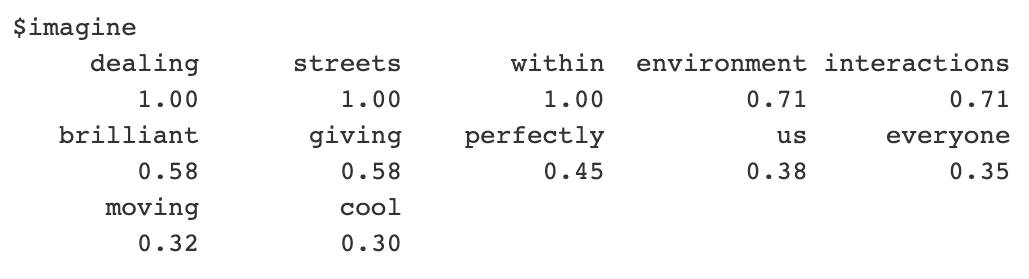

[6.4] Another word that I was interested in from the matrix was the word "imagine." In the comments, some of the associated words were "dealing," "moving," "environment," and "interactions." The findAssocs() similarly shows examples of close reading within the comments and notes the literary terms that readers use to understand a work's intratextual connections. For example, in figure 4, the term "imagine" was used to collate associated terms. Some associated terms are "giving," "us," and "perfectly," which denote the ways that users interact with the text and how they use their close reading skills to frame their perspectives on the work.

Figure 4. A termAssoc() of the word "imagine" from Ruby's comments.

[6.5] The purpose of analyzing associated terms was to determine the connections that a reader was making between the text in the comments. By analyzing the road maps (associations) that appear between words, one can begin to draw conclusions about how readers are making paratextual relations to other works, a form of analysis taught in secondary literature classrooms. As Showalter (2002) highlights, "When we teach reading literature as a craft, rather than as a body of isolated information[,] we want students to learn […] how to relate apparently disparate works to one another, and to synthesize ideas that connect them into a tradition or a literary period" (26).

7. Topic modeling

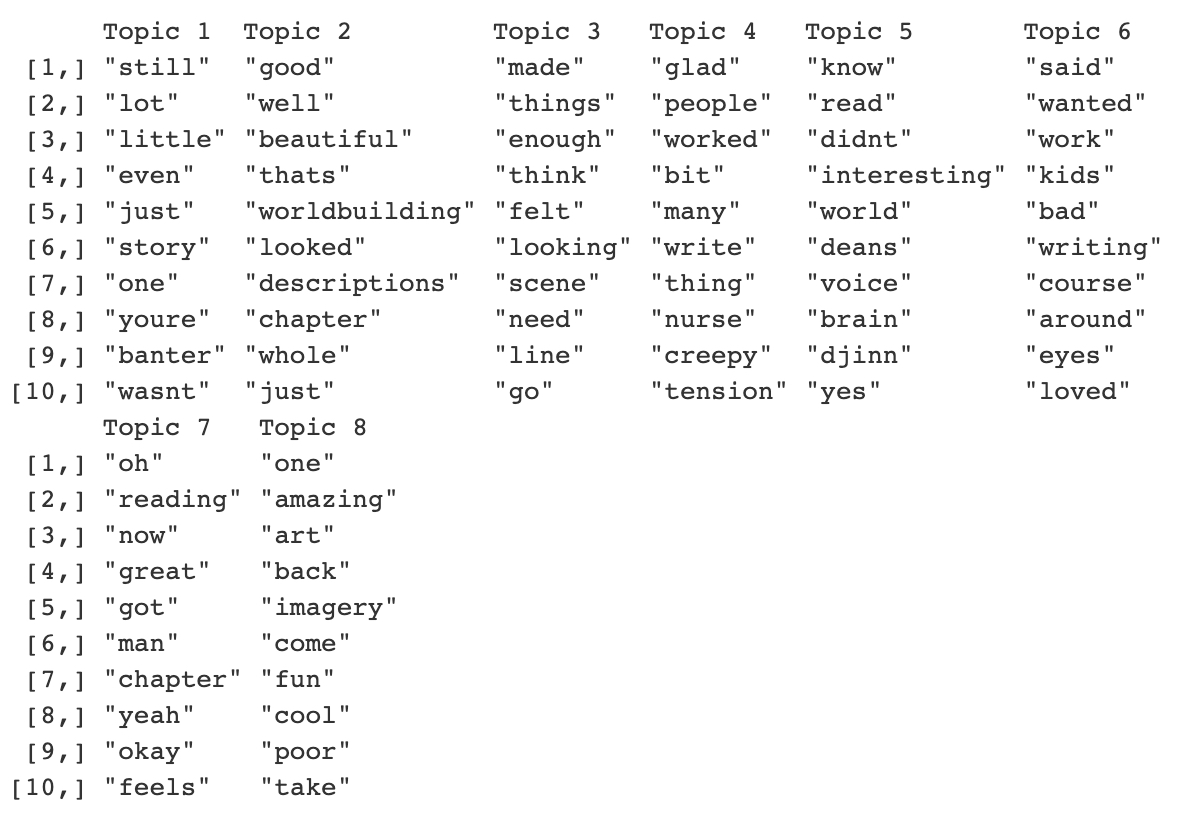

[7.1] Another type of analysis that I conducted was topic modeling, or latent Dirichlet allocation analysis (LDA). Topic modeling is a form of classification of documents, and this analysis was conducted through the (topicmodels) R library. LDA is a generative probabilistic model through which each document is treated as a mixture of topics based on sets of frequently occurring words within the documents, and it clusters documents on the basis of their level of association with particular topics (Blei, Ng, and Jordan 2003). Topic modeling is beneficial, especially to this kind of analysis, because it predicts which words might be most closely associated with one another, allowing for groups to be formed. The forming of groups then allows someone to look across a data set and make predictions about what is being discussed and how it is being discussed, as well as how it might relate parts of a data set to a whole set. The number of topics and words included in each topic is customizable, but the more topics you have, the more words will repeat within each topic. Initially, I started out with five topics and ten words in each topic. This yielded topics and words that did not overlap; however, it also did not show any correlations between topics. Essentially, the fewer number of topics, the more outliers in the data. As I increased the number of topics, I was able to ascertain overlap among them, and the data began to look like a cohesive set, with fewer outliers. I established that eight topics was a reasonable number for this body of comments, and I specified that each topic would comprise ten individual terms (table 1).

| Topic no. | Individual terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | "still," "lot," "little," "even," "just," "story," "one," "youre," "banter," "wasnt" |

| 2 | "good," "well," "beautiful," "thats," "worldbuilding," "looked" "descriptions," "chapter," "whole," "just" |

| 3 | "made," "things," "enough," "think," "felt," "looking," "scene," "need," "line," "go" |

| 4 | "glad," "people," "worked," "bit," "many," "write," "thing," "nurse," "creepy," "tension" |

| 5 | "know," "read," "didnt," "interesting," "world," "deans," "voice," "brain," "djinn," "yes" |

| 6 | "said," "wanted," "work," "kids," "bad," "writing," "course," "around," "eyes," "loved" |

| 7 | "oh," "reading," "now," "great," "got," "man," "chapter," "yeah," "okay," "feels" |

| 8 | "one," "amazing," "art," "back," "imagery," "come," "fun," "cool," "poor," "take" |

[7.2] Topic modeling was the final form of data analysis used to study Ruby's original story. While the manual analysis of this work allowed me to look at the comments as a whole, topic modeling showed semantic meanings within the structures of the comments via the signifiers between words, signs, and symbols and what they stand for in accordance with their denotations. From there, topic modeling allowed me to draw abstract conclusions about groupings of topics as well as about who was writing the comment and what metatextual and intertextual connections they were making as they read Ruby's story. This is valuable as it shows the skills that readers have been taught (those text-to-text and text-to-world connections) in real time. Topic 2, which I found particularly interesting, related to Ruby's skill as a writer. For example, readers commented on her world-building ability: "The description of the city sets the scene and the area up so well. You world-build like it is an original and I can see your love in it." Taken together, all the data on topic 2 indicated that Ruby and her story's readers prized evocative, rich descriptions, which made them think about how this text might relate to others.

[7.3] Topics 3 and 4 at first glance seem like responses from the author, as words like "glad," "people," felt," and "write" are often used to express gratitude to readers for their attention. However, the two separate topics also highlight the comment threads where the author responds to readers and vice versa. For topic 4, for example, combining the mode of topic modeling with the mode of term associations revealed the presence of correlations: There were twenty-nine instances of the word "glad" in the comments, and twenty-six of these were in Ruby's comments. Topic 3 is also highly correlated with responses from the author. Manual analysis shows that the word "felt" is used most frequently in quoting the text of the fic in Ruby's indirect responses. Of the twelve uses of "felt," seven quoted the story and three were responses from the author. Similarly, when looking at the other topics (figure 5), words like "looking" and "scene" appear both in readers' comments as quotes from the text and in Ruby's replies to readers. This reiteration of Ruby's wording—from fic to fic quoted in a comment to author response to comment—demonstrates the importance the community places on various criteria, with their repetition indicating the various steps that Ruby takes to build relationships around her writing.

Figure 5. Topic modeling for Ruby's comments.

[7.4] As I've just shown, topics and word frequency can demonstrate the methods fan authors and their readers use to build a community through writing, reading, and commenting on a fic. In topic 7, the words "made," "felt," and "looking" were correlated with readers' placing themselves into the scenes described in the story. One reader said, "Suddenly brain matter…that was unexpected! I like all the details Dean is taking in even in this chaos…as a good runner should! This reads really smoothly. Everything is happening all at once, but I never felt lost or confused." This reader is reading the fic immersively, making connections to their own life and to their past education about reading and writing. The reader connects their past readings of difficult and unfamiliar texts and maps these experiences onto this story intertextually while simultaneously inserting themselves and their writing experiences into the story. As this exchange demonstrates, fandom spaces may be used as spaces of learning and connecting.

[7.5] As a product of the English literature classroom and a former English literature teacher in public middle school (seventh and eighth grades), I have seen firsthand the pedagogy of literature and the types of skills taught when analyzing a piece of text. Further, literary theory has always had a place in the secondary literature classroom. There has always been a connection between reading theories and literary theories, reaching back to the thinking of Kenneth Goodman and Wolfgang Iser. Teaching techniques of literary theory like close reading, paratextual connections, and figurative language allows for students to learn and adopt critical thinking processes, a skill that in turn permits the analysis of media artifacts, physical texts, and a host of other genres outside of the classroom, like fan fiction (Appleman 2015; Misson and Morgan 2006; Karolides 2013).

8. Conclusion

[8.1] Each form of data modeling and analysis highlighted a different aspect of the comments on Ruby's work, and overall, each analysis demonstrated the clear presence of learned methods of literary analysis. The documentary analysis highlighted surface-level details apparent in the comments, while textual modeling and word frequency analysis demonstrated the specific patterns of language used in Ruby's and the readers' comments. This provided an overview of the topics that readers focused on in their analyses of Ruby's fic, topics that were further highlighted by the associated terms analysis. The associated term analysis allowed links to be made between learned methods of literary analysis and Ruby's fan fiction, as seen through the analysis of the word "looking" in the comments. Finally, topic modeling emphasized possible intra- and intertextual connections made by Ruby in her fan fiction and by the readers in their analyses of her fan fiction, as well as how the readers and Ruby built a sense of community through the comments.

[8.2] The comments on Ruby's work demonstrate the intricacies of reading fan fiction. Fans' comments indicate that they pay attention to the (formal) techniques that authors use as they write, edit, and publish a story. Fans continually make inter- and intratextual references and are able to apply their knowledge of literary modes, structures, and styles. The figures that illustrate my analyses above visualize the ways that fans use close reading skills when reading fan fiction. Fans may emphasize figurative language such as personification or extended metaphors in their comments, as the visualizations of the data show, indicating community approval of this mode and reinforcing such word usage. Furthermore, certain words used in the comments may connote types of learning or responder attitudes, as demonstrated in the topic modeling. More, these concordances show how fans read beyond the source text, making connections to other media. Close readings and critical analyses in the comments show that fans are using skills valued in traditional classroom settings in their leisure time. This suggests that incorporation of fan fiction into the classroom could improve students' multiliteracies.

[8.3] This study is not without its limitations, not least of which is the convenience sampling in response to an online call, which privileges a particular mode and practice of fan writing (chaptered media-based fan fiction workshopped and published online in the English language). Further, I may have been biased when I chose the codes to organize the data. However, this analysis is novel in that it performs quantitative analysis of fan texts in an attempt to better understand the intertextual process of fan creation of written texts.

[8.4] Several points invite further study. Studies examining word and term frequency would be welcome; in particular, the latter suggests several promising avenues for future research, including looking at the word "thank." "Thank" is used by both authors and readers in the comments, but its implied meanings vary. In particular, studies using lemmatization—that is, the grouping of similar or synonymous words—would offer valuable insight into topics frequently discussed in comments. Lemmatization of "thank" would group words like "thanks," "thank," and "thanked" as well as synonyms like "gratitude." By consolidating variations, inflections, and synonyms of the words being considered in the study, lemmatization can provide deeper nuance in a data set, especially in terms of data visualization. Finally, outside arenas of interaction, such as Tumblr or Discord, should be taken into account in addition to the comments on fan fiction archive websites, as these social media sites are popular arenas in which the discussions undertaken on the fic's archive site are extended.

9. Acknowledgments

[9.1] Thank you to Dr. John Shanahan, Dr. Paul Booth, and Dr. Ana Lucic for this assistance on this project during my Masters degree, and to Dr. Mel Stanfill for their assistance in editing and preparing this work for publication. An additional thank you to Dr. Kristina Busse for her assistance in this process and to the many fan studies graduate students and scholars who have offered words of encouragement throughout this research.