1. Introduction

[1.1] Ouen-jouei, or "cheer screenings," offer Japanese cinema audiences a novel experience. While film audiences are typically forbidden from any disruptive behavior—such as talking or moving—during screenings, ouen-jouei events actively encourage certain forms of "disruptive" behavior, including cheering, the use of glowsticks, and cosplay. Such activities enable a stronger connection between audience members and the story world of the movie. Emerging in 2016, cheer screenings have become exceptionally popular, particularly among anime fans. Ouen-jouei events thus offer new insights into the ways in which fans immerse themselves within and explore story worlds.

[1.2] Ouen-jouei events offer a stark contrast to traditional movie theater culture in Japan. Japanese movie theater history and audience culture can be divided into the eras before and after the birth of the cinema complex in 1993. According to Katoh (2006, 166), Japanese cinema complexes require "absolute silence" from audiences. From the outset, cinemas have implemented strict rules governing audience behavior. Indeed, before a film starts, Japanese cinemas play a short film warning against the use of mobile phones, speaking, or disruptive actions of any kind. However, this has changed with the emergence of ouen-jouei. I here trace the emergence of ouen-jouei from its emergence in 2016 in the King of Prism fandom. I share the results of an observation- and survey-based study of King of Prism fans' participation in ouen-jouei events and their immersion in the King of Prism story world. I first present the data and then analyze them using theories of immersive participation. During this analysis, I discuss and examine the specific features of ouen-jouei performances that help audiences immerse themselves in a story world.

2. Ouen-jouei and King of Prism

[2.1] As noted, ouen-jouei is a special type of movie screening that allows the audience to cheer, use glowsticks, and engage in cosplay at the movie theater. Western audiences have engaged in similar screenings, particularly for musical films like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and Frozen (2013). However, there is a definitive difference between such screenings and ouen-jouei, as the latter occurs within an audience culture that frowns upon any expression during screenings, including laughter or clapping. Indeed, Japanese audiences believe that only silence is appropriate when watching a film (Tsuchida 2017, 28). Of course, there were several precursors to ouen-jouei in Japan. Sporadic attempts to foster audience participation included encouraging audience members to cheer for characters by shaking glowsticks for the Pretty Cure (2004–) series, as well as spontaneous cheering at Muthu (1995) screenings in 1998. Nonetheless, the emergence of ouen-jouei in its present form was triggered by the release of King of Prism (hereinafter, Kinpri) in 2016 (Koarai 2019).

[2.2] The popularity of ouen-jouei for Kinpri was spread by online anime fan communities, making it an unexpected big hit (Mantanweb, April 24, 2016.). Initially released to just fourteen cinemas, the popularity of ouen-jouei events saw Kinpri enjoy a run longer than nine months at cinemas across Japan. Indeed, anime fans were so enthusiastic about ouen-jouei events for the film that they attended dozens of screenings. According to Kiyo (2016), many attendees of ouen-jouei events for Kinpri in Tokyo and Osaka claimed to have attended more than ten such screenings, while one boasted attending over fifty. Attracting national media attention (@kinpri_PR, September 13, 2017), the massive success of the film led to ouen-jouei events for other movie titles and in other Asian countries. Indeed, similar screenings were held in Korea and Taiwan, with ouen-jouei becoming a particularly popular format in Korea (Mantanweb, November 18, 2016).

Video 1. Ouen-jouei introduction video created by Avex Pictures (2016b), the King of Prism distribution company.

[2.3] The Kinpri series includes three works: King of Prism by Pretty Rhythm (2016), King of Prism: Pride the Hero (2017), and King of Prism: Shiny Seven Stars (2019). The anime series includes both a movie and television shows about characters who each aspire to be a Prism Star: idols performing a Prism show that combines figure skating, singing, and dancing. Kinpri's ouen-jouei began as a special screening conducted by Kinpri's producers. Since King of Prism by Pretty Rhythm (2016) was released in movie theaters throughout Japan, Kinpri's ouen-jouei have been held in addition to ordinary screenings that forbid cheering. In the beginning, ouen-jouei screenings were not held every day. However, after Kinpri grew in popularity, ouen-jouei were held every day, in addition to ordinary screenings at most movie theaters. After daily screenings stopped, Kinpri's ouen-jouei continued to be held on the characters' birthdays and other important dates.

[2.4] Ouen-jouei is almost identical to ordinary movie watching, except that it encourages audience participation. Anyone can reserve a ticket and participate in ouen-jouei at a movie theater in the same manner as other movies. Ouen-jouei screenings are also held in the same way as other ordinary screenings, and they do not include live actors. In other words, the only difference between ouen-jouei and an ordinary screening is audience performance and participation.

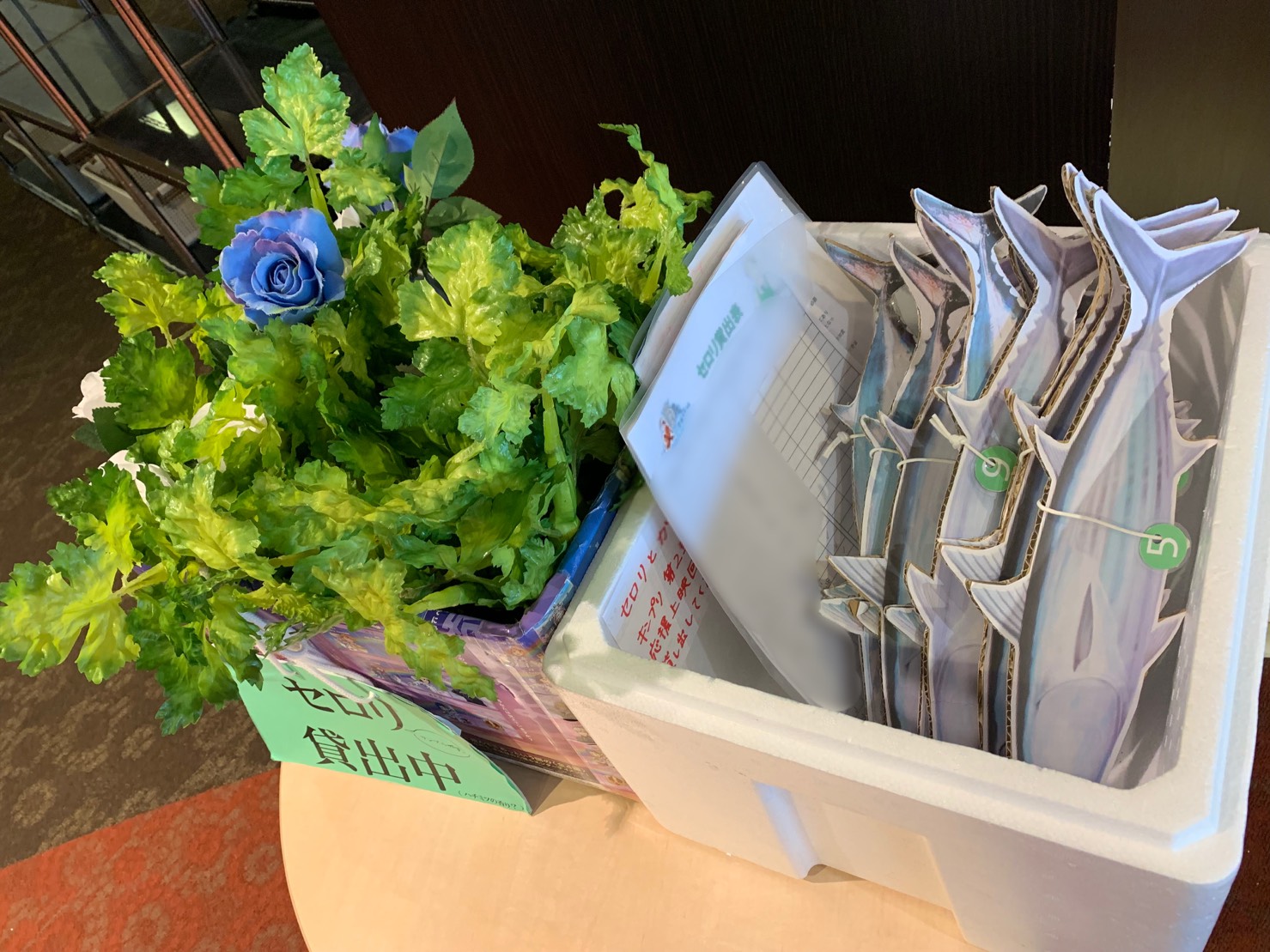

[2.5] Most audience members participate in ouen-jouei with glowsticks (figure 1), while some bring paper fans and happi coats with movie characters printed on them. This cheering style echoes the cheering style common to pop idol fans in Japan. Furthermore, some audience members enjoy cosplaying as movie characters (figure 2), and some bring cheering material linked to the movie, such as plastic celery, roses, or animal toys (figure 3).

Figure 1. Glowsticks illuminate and change into more than ten colors. Author's photo.

Figure 2. The audience cosplays as movie characters at the movie theater. Author's photo.

Figure 3. Some movie theaters lend audiences members materials for cheering. The sign says, "Now available for rent: Celery." Author's photo.

[2.6] During the screening, ouen-jouei audiences often begin performing from the moment they are seated. For example, viewers light green, orange, or white glowsticks in response to commercials for Seven Eleven. Typically, after a short film about viewing manners, the ouen-jouei screening begins. The main story of Kinpri includes some background drama as well as a Prism show. In the drama part, the audiences respond to a character's lines, root for them, or trace their actions. For example, when one character says, "Hey," to another character, the audience also responds, "Hey!" During a training scene, the audience roots for characters by shouting, "Way to go," or "You can do it!" In other scenes, the audience may synchronize their glowstick movements to those of a character's wand. Moreover, the drama portion also includes one special scene called prism af-reco during which captions appear on the screen in response to a character's line. The audience is expected to read these captions like a voice actor. For example, one character asks, "Are you ok?" Next, the caption "No problem!" appears on screen. By reading this caption, the audience can feel like they are conversing with the movie character as another character. In the Prism show portion, the audience cheers for the characters by shaking glowsticks and applauding as if they were at a live idol concert.

[2.7] These cheering methods are similar to Japanese fans' performances for sports players, Kabuki actors, and idols. In addition, as seen in prism af-reco, Kinpri is partially designed on the assumption that viewers will participate in ouen-jouei. However, as will be discussed later, ouen-jouei audiences are neither passive nor controlled by the producers but rather create many original forms of participation, reflecting traditional fan cultures' tendency towards transformation. As a result of the story and the innovative style of screening, which allows for new applications of familiar practices, ouen-jouei was especially compatible with Kinpri and Kinpri audiences.

[2.8] It is important to note, here, that the diffusion of ouen-jouei throughout Japan and Asia did not result from audience frustration with the strict rules of movie theaters. Rather, the primary cause can be found by observing the performances of ouen-jouei audiences, who immerse themselves in the story world of a movie through the particular physical activities promoted by ouen-jouei. This prompts the question of what specific activities are necessary for audience immersion in a story world, as well as what features define immersion at ouen-jouei events. Answering these questions enables us to consider a more general issue in audience, media, and fan tourism studies, namely, how immersion actually occurs. As Kischuk (2008, 21) notes, "While the pleasures of immersion may stem from narrative, this still leaves the question of how exactly that immersion is achieved: that is, how do people become absorbed in story?"

[2.9] In order to address these questions, this study examines the ways in which Japanese popular culture fans become immersed in the story world of a film through ouen-jouei events, focusing on the Kinpri series. The Kinpri series was selected for three reasons: First, as noted, the Kinpri series triggered the emergence of ouen-jouei. Second, in comparison to other movies, ouen-jouei of the Kinpri series was enacted regularly, making it the optimal series through which to consider patterns of ouen-jouei performance. Third, the Kinpri movies have enjoyed the greatest popularity of all ouen-jouei events in Japan and Korea, and as such, have developed established ouen-jouei audience practices.

[2.10] This study obtained data from two sources: First, I conducted participant observation of ouen-jouei events sixty-seven times at nineteen movie theaters in Japan and Korea. Second, I disseminated a questionnaire to ouen-jouei audiences after a screening at two movie theaters in Hokkaido and Tokyo. Data analysis reveals that ouen-jouei audiences become immersed in a story world through two kinds of performative acts: cheering and the use of glowsticks. These performative acts are different from normative uses of cheering and glowsticks such as cheering by sports fans or Kabuki audiences or the use of glowsticks at dance clubs or night-time amusement parks, which do not lead to immersion. As this study shows, ouen-jouei events encourage immersion through three types of cheering (rooting for the films' characters, conversing with the characters, and becoming one with the world of the film) and two uses of glowsticks (the actual usage of glowsticks and assimilation with the world of the movie). Their immersion involves the recognition of the distinct physical boundary between the real world and story world. Immersion in a story world is also achieved through a process of "perpetual negotiation" (Wynants, Vanhoutte, and Bekaert 2008, 161) between their sense of self as a spectator watching the movie in the real world and their sense of self as existing within the story world.

3. Immersion in fan tourism studies and media studies

[3.1] This study uses the concepts of explicit interactivity and immersive production to analyze audience immersion in cinematic story worlds through physical performance at ouen-jouei events. As such, before I discuss my methodologies, it is necessary to define several of the terms used in this study, starting with "story world." Scholars have used a variety of terms for this concept, including Marie-Laure Ryan's "fictional world" (2002, 590) and Catherine Bouko (2014)'s "textual world" (5), "literary world" (11), "created world" (11), and "imaginary world" (13). This study understands "story world" to refer to an imaginary world created by a story. A story world, then, "consists of a world (setting), populated by individuals (characters), who participate in actions and happenings (events, plot), through which they undergo change (temporal dimension)" (Ryan 2002, 583).

[3.2] Story worlds are often linked to the concept of immersion. The term "immersion" has subtly different meanings in different fields of study. Biggin (2017) provides some definitions of immersion relevant to the audience's immersive experience. According to Biggin, immersion with VR or multimedia in hybrid environments "implies the sensation of being physically surrounded, although not (necessarily) the sensation of being mentally/emotionally engaged" (22). Meanwhile, in game studies, "immersion is defined primarily as occurring within the mind of the gamer—their thoughts, feelings, and so on—many studies define immersion as a cognitive process" (44). As regards the immersive experience of theater, Biggin notes that there "is a fleeting state of engagement which can assume different forms and various levels of intensity" (44). These partially overlapping definitions touch on the immersion cultivated by ouen-jouei.

[3.3] However, the present study understands immersion as the means of approaching a story world. It thus defines immersion as "a strong fantasy identification or emotional connection with a fictional environment, often described in terms of 'escapism' or a sense of 'being there'" (Jenkins 2006, 286). In other words, immersion in a story world refers to an individual's emotional identification with that world. Such immersion is remarkably similar to the sense of presence, that is, "the feeling of 'being there,' of feeling at one with the work" (Biggin 2017, 5). Furthermore, "immersive production" in this article is defined as various productions (for example, immersive theater, VR games, theme park attractions, and screening events) that are designed by the producer to encourage the audience's immersion in the story world. In order to analyze the feature of audience immersion in a story world through ouen-jouei performances, this study adopts audience studies, media studies, and fan tourism studies as its theoretical frameworks. These complementary fields enable the analysis of the process by which ouen-jouei audiences immerse themselves in story worlds, as well as their affective experiences when doing so.

[3.4] Recently, scholars in the field of audience studies have examined audiences' experiences and their immersion in different kinds of immersive or participatory productions that tend "to take place outside the cultural auditorium and to engage audiences in non-seated, non-static, non-representational, and otherwise non-traditional ways" (Sedgman 2018, 13). In terms of the participatory culture of art in general, Conner (2016, ¶ 18) refers to the audience's involvement in the process of understanding the universe of the work as "the audience member as learner." Hills (2017, 492) describes secret cinema's potential to "become theatricalized as a themed experience for cosplaying participants." In addition, Atkinson and Kennedy (2016, 274) have examined immersion in secret cinema screenings, which are "more akin to an immersive theme park attraction (with costumes! and a screening!) than live theater or games." In doing so, they note "the inherent dichotomy in immersive cinema events" (273): when an event switches from activities in physical space to a movie screening, audiences "switch abruptly between two participatory registers," namely, from "one of full active (and at times challenging) immersion" to "a highly conventionalized arrangement of participants in rowed seating in front of a large screen" (272). These studies discuss the audience's cinematic experience accompanied by physical performance.

[3.5] Meanwhile, Grainger and Minier (2019, 41–42) have examined a street performance by Yello brick, which invited passers-by to experience the world of a Tudor opera through the performers' semichoreographed movements in the city. This article provides a case wherein the audience is led into a story world through the actor's physical performance. Scholarship located at the intersection of audience studies and media studies provides a more concrete analytical view for this article. Drawing on game studies, Biggin (2017) applies the multivalent model developed by Salen and Zimmerman (2003, 59–60, 69) to immersive theater. Biggin (2017, 89) describes the notion of "explicit interactivity" in reference to directions given to an active audience to perform physical action.

[3.6] Numerous media studies scholars have examined immersion in story worlds, primarily focusing on VR or computer game worlds, as well as the worlds of immersive theater (e.g., Bouko 2014; Ryan 2002; Wynants, Vanhoutte, and Bekaert 2008). Bouko's (2014) model of immersive theater offers an especially productive means of examining the process through which media consumers become immersed in a story world. According to Bouko (2014, 12), the model of immersive theater comprises the following three steps:

[3.7] I. Physical integration vs. breaking down frontality

II. Sensory and dramaturgical immersion

a. Placing the immersant at the centre of an environment, between simulation and representation

b. The immersant's dramaturgical integration, first person dramaturgy

III. Immersion and spatiotemporal inderteminacy [sic]

[3.8] In this model, immersion "depends on bodily perception rather than language" (Bouko 2014, 14)—indicating a difference between this type of immersion and that achieved through reading. Moreover, this type of immersion "includes a more developed narrative dimension than most virtual reality installations" (14), making it different from the immersion evoked by installation artworks. In this respect, Bouko's model facilitates the analysis of how media consumers become immersed in a story world through specific physical actions. However, due to the features of immersive theater, this model needs "to dissolve the division between the stage and the audience in order to achieve immersion" (12). As such, immersion theater's story world is enacted in the same dimension as the audience—that is, the story world of the production and the audience "share the same space" (Biggin 2017, 23). As with computer games, the ouen-jouei audience is "physically distant from the screen" (23). It is therefore impossible to physically integrate the audience and the story world of the ouen-jouei movie setting. Consequently, this model is inadequate for examining immersion in the story world of a movie, piece of literature, or computer game.

[3.9] Fan tourism studies provide a means of overcoming the limitations of Bouko's (2014) model for the subject of this study. Fan tourism is a close relative of fan pilgrimage, media tourism, pop culture tourism, literary tourism, and contents tourism. This article adopts Godwin's (2017) understanding of fan tourism as a fan practice that is motivated by a tourist's desire to be closer to or to make a connection with a story world. Fan tourism scholars have analyzed fans' immersions in story worlds that transcend the physical barrier between the real and imaginary world (e.g., Godwin 2017; Kischuk 2008; Reijnders 2011). For instance, examining Dracula tourism—that is, the Dracula fan practice of visiting Transylvania and looking for traces of Count Dracula—Reijnders (2011, 241) argues that Dracula fans' tourism constitutes an extension of the "suspension of disbelief" promoted by films and literature, as well as "the willingness to accept the world of the imagination as real." Meanwhile, analyzing fan immersion at the Harry Potter theme parks, Godwin (2017, ¶ 1.9) argues that "The field of fan tourism allows for discussions of extending the suspension of disbelief required for enjoying fiction into the physical world. Fans suspend disbelief not only while reading books or watching screens but also when they experience a theme park's rides and attractions: physical manifestations of story worlds previously encountered in books, films, video games, and other media windows. Not only a fan's mind but also a fan's body experiences immersion in a story world via such suspension of disbelief: both conceptual and physical immersion."

[3.10] Unlike the model of immersive theater, this aspect of the suspension of disbelief enables the analysis of immersion in a story world that transcends the physical barrier between the real and imaginary worlds through physical performance. Accordingly, by adopting a framework combining media studies and fan tourism studies, this study examines the process by which ouen-jouei audience members become immersed in a story world.

[3.11] Fan tourism studies also address the inner experiences of individuals when they immerse themselves in a story world (e.g., Godwin 2017; Reijnders 2011; Seaton et al. 2017). Reijnders (2011, 232–33) describes the inner experience of Dracula fans' immersion in the Dracula story world in and through Transylvania—one of the settings of the novel—as follows: "The Dracula tourist is characterised by the dynamic between two, partially opposing, modes. While Dracula tourists use rational terms to describe their desire to make concrete comparisons between imagination and reality, they are also driven by an emotional longing for those two worlds to converge. What these two modes have in common is their distinctly physical foundation: they are both based on a sensory experience of the local environment."

[3.12] Thus, according to Reijnders (2011, 245), a Dracula fan's inner experience is characterized by "the tension between two partially contradictory modes": on the one hand, individuals seek to compare the real world to the story world in a logical and rational manner; on the other hand, individuals wish to be "'closer to the story' and to make a 'connection' through a symbiosis between reality and imagination" (245). This is important to consider when exploring the inner experience of media consumers as they become immersed in a story world. However, Reijnders does not specifically analyze or describe how fans access a story world, or the tensions between these two partially contradictory modes.

[3.13] Media studies approaches complement the above arguments. Ryan's (2002) model index of interaction between users and the virtual world is useful for explaining how fans access a story world through the tensions between the two partially contradictory modes identified by Reijnders (2011). Combining two binary pairs—namely, "internal/external" and "exploratory/ontological"—Ryan (2002) divides the interaction between gamers and the world of VR games into four groups. Incidentally, a difference in exploratory/ontological modes is that "the user either does, or does not, have the power to intervene in the affairs of the fictional world" (596). In the exploratory mode, users can explore the story world but cannot create or change the plot. Meanwhile, in the ontological mode, users can create or change the plot of the story world, as well as explore the story world. Group one comprises "external-exploratory interactivity," wherein users explore virtual worlds from an external time and space, with their exploration unable to influence the virtual worlds (596). Group two comprises "internal-exploratory interactivity," wherein users explore the virtual world from an internal time and space; however, their exploration cannot affect or rewrite the virtual world (597). Group three comprises "external-ontological interactivity," wherein users explore the virtual world from an external time and place but can make changes to the setting of the virtual world (598). Finally, group four comprises "internal-ontological interactivity," wherein users explore the virtual world from an internal time and space and can make changes to the virtual world (601). Accordingly, this model enables us to examine how consumers access a story world through the tensions between two partially contradictory modes, identifying whether consumers do so from an internal or external time and place and whether they adopt an exploratory or ontological approach.

[3.14] Finally, the concept of "transitional space" helps explain the tension between the two partially contradictory modes. According to Wynants, Vanhoutte, and Bekaert (2008, 162) tension is "the negotiation between the real and the frame, between 'looking through' and 'looking at,'" and thus "enhances 'our sense of being there'" in the story world. More specifically, the negotiation between different levels of perceived reality results in "a confusing experience, increasing the corporal awareness of [being] in a transitional environment" (161). Combining approaches from audience studies, media studies, and fan tourism studies, this study's framework of analysis serves as an extension of these theories.

4. Method

[4.1] This study investigates what specific performances are enacted by ouen-jouei audience members to achieve immersion in the Kinpri story world and identifies the features of this immersion. The study employed two methods to gather data: audience observation and a questionnaire survey.

[4.2] First, to be able to accurately describe and analyze the specific performances enacted by audience members, this study observed audience participation at sixty-seven ouen-jouei Kinpri screenings at nineteen theaters in Japan and Korea between 2016 and 2019. Distributors do not offer a single, standardized norm of performance for such screening events. Therefore, audience ouen-jouei performance is spontaneous, its characteristics unique to each screening and location. Indeed, Hishida, the film's director, noted that "there are regional characteristics in performance of ouen-jouei" (quoted in Murakami 2016). However, this study did not conduct observations at multiple screenings and theaters with the intention of comparing regional characteristics in ouen-jouei performance but rather to consider common characteristics.

[4.3] Second, to investigate the inner experience of ouen-jouei audience immersion in the Kinpri story world, this study disseminated a questionnaire twice: at the Dinos Cinemas Sapporo in Hokkaido, Japan, on August 4, 2017, and at the Shinjuku Wald 9 in Tokyo, Japan, on September 11, 2017. Permission was granted by each theater and movie production committee. The questionnaire was distributed to the audience as they exited the film and answered via a Google form; twenty-one responses were collected.

[4.4] This study employs triangulation to analyze the qualitative data. By indicating the same kind of result with other objective and public data, triangulation allows the qualitative data to be safeguarded against subjective bias and ensures reliability. The analysis is supplemented by videos showing the performance at ouen-jouei events, which add an objective perspective. This study also uses findings in the extant literature regarding ouen-jouei audiences to supplement the subjective answers provided by questionnaire respondents. These data help ensure the reliability of the qualitative data presented here.

5. Audience performance at ouen-jouei

[5.1] Audience participation observation revealed two common characteristics of audience immersion at ouen-jouei events: namely, cheering and the use of glowsticks. These characteristics can be broken down further. Cheering comprises three aspects: rooting for the film's characters, conversing with the characters, and becoming one with the world of the film. Use of glowsticks comprises two elements: first, actual usage of the glowsticks, and second, assimilation with the world of the movie. This section discusses these findings in greater detail.

[5.2] As noted, the first element of cheering is rooting for the movie characters. For example, when one of the movie characters exclaims, "My seniors will not lose to you," the audience respond, "Exactly! Exactly!" Similarly, when a movie character cries, the audience yell, "Please don't cry!" This kind of engagement is similar to the rooting for soccer players by supporters or oomukou, the yelling by audiences at actors during Kabuki. However, these forms of audience performance differ from that of ouen-jouei insofar as the target of their support exists in the real world, while that of ouen-jouei lies in a story world. Unlike soccer players and Kabuki actors, there is a physical separation between the audience and the anime characters on the screen. While the support of ouen-jouei audiences cannot reach the film's characters, the audience provide support as if they are real.

[5.3] The second element of cheering is the audience's conversing with the movie characters. For example, when one of the characters says, "There is something I want to say to everyone," the audience ask, "What?" Similarly, the audience yell out the answer when a character asks another character, "What food don't you like?" This type of performance constitutes a conversation between the audience and the film's characters. In such moments, the audience behave as though they are in the same space as the characters on the screen.

[5.4] The third element of cheering is becoming one with the world of the movie. For example, Kinpri has prism af-reco—that is, after recording—that allows the audience to read the lines of the movie characters. In the prism af-reco scenes, subtitles are displayed on the screen and the audience can assimilate with the movie characters by saying these lines. Prism af-reco is provided by the distributor. However, the survey conducted by this study revealed other ways in which the audience become one with the world of the movie. For example, when a film's character who is an idol finishes a live performance at a concert venue, the audience acts as though they are part of the onscreen concert audience by cheering and applauding. Through such performances, the audience immerse themselves in the world of the movie.

Video 2. This video shows the audience's rooting for and interaction with prism af-reco at an ouen-jouei event (Avex Pictures 2016a).

[5.5] As noted, the second characteristic of audience immersion is the use of glowsticks. The first element of this is the actual usage of these props. For example, during scenes in which characters are playing to live audiences onscreen, the film's audience shake their glowsticks, which emit colors symbolizing the movie character that is performing on the screen. This kind of performance is the same as any fan cheering a live performance. However, the ouen-jouei audience is cheering for a fictional live performance that is only live in the story world of the movie. As such, the ouen-jouei audience assimilate with the audience on screen through the use of glowsticks.

https://twitter.com/i/status/890481377245671424

Video 3. In this video, the audience uses glowsticks emitting the color associated with a specific character to cheer their favorite idol's live performance at an ouen-jouei event during the Seoul International Cartoon and Animation Festival (2017).

[5.6] The second aspect of using glowsticks is the audience's assimilation with the world of the movie. In some scenes, the audience synchronize their glowstick actions with those of the wand, a wooden sword or blade wielded by a movie character. The audience also imitate any motif in the movie; for instance, during a scene in a church, the audience depict a symbol of the church by making a cross with white glowsticks. Similarly, the audience use their glowsticks to represent onscreen situations such as mimicking shooting stars using white glowsticks, depicting thunderstorms by shaking yellow glowsticks, and illustrating snowstorms by swinging white glowsticks. Called sairium-gei, or "trick of glowsticks," in Japanese, these performances help ouen-jouei audiences assimilate themselves with both the movie character's actions and events of the story world.

Video 4. This video shows the audience synchronizing their glowstick movements to that of the wand used by the character onscreen (Avex Pictures 2016c).

[5.7] As such, this study observed the following specific actions from ouen-jouei audiences that facilitated their immersion into the film's story world: First, the audience become immersed through cheering—specifically, by rooting for and conversing with the characters, as well as by behaving as one of the movie characters. Second, the audience use glowsticks to cheer the characters onscreen and assimilate with the story world. These actions enable ouen-jouei audiences to achieve emotional immersion in a story world and gain a sense of being there.

6. The inner experience of ouen-jouei audiences

[6.1] In order to analyze the features of ouen-jouei audiences' immersion in the story world, this section examines the process of this immersion and the inner experience of Kinpri ouen-jouei audiences based on the survey and questionnaire results. The questionnaire distributed to ouen-jouei audiences asked respondents, "What is the difference between ouen-jouei and ordinary screenings?" Some reflected on Kinpri's storyline—which involves the live performances of idol characters—noting that ouen-jouei performances provide "a sense of unity in the theater and a feeling as if we were really at the venue of the Prism show." The majority of respondents noted that the difference "is that we can get into a story world" and "the audience becomes immersed in the story world" at ouen-jouei events. Audience participation and assimilation were pointed out objectively. According to Nishi—the series' producer—the interaction of fans at ouen-jouei events led to new experiences at each screening: "In spite of the same story being screened, the fan gets the impression that 'at today's movie, my favorite character's dance is better than the last time I watched the movie'" (quoted in Kobayashi 2019, 14). According to Sugawa, a scholar of 2.5-dimension culture, the popularity of such events in contemporary Japan lies in the fact that "the immersion makes the audience feel part of the fictional world" (quoted in Katoh 2019, 29).

[6.2] These findings indicate that the experience of ouen-jouei audiences is the equivalent to the immersive theater model, that is, "a presentational or theatrical form or work that breaks the 'fourth wall' that traditionally separates the performer from the audience both physically and verbally" (LUX Technical Ltd. 2019)—particularly in regard to Bouko's (2014, 260) notion of "sensory and dramaturgical immersion." In other words, the ouen-jouei audience member is "sensorial and physically plunged into an imaginary world to which he belongs" (262) and becomes assimilated in the story world. It can be argued that at ouen-jouei, interactivity appears as explicit interactivity. In this respect, while the audience can select and enact any action within the rules of immersive productions, they cannot influence or change the production. Accordingly, explicit interactivity is "a one-way type of 'interactivity'" (Biggin 2017, 67) and not absolute interactivity. Nonetheless, in immersive theater, explicit interactivity is capable of giving a "more fulfilling immersive experience" (90) by encouraging audiences to perform physical actions such as exploring the venue, opening the door, and moving from one room to another. This situation echoes the "thinly interactive" (Atkinson and Kennedy 2016, 259) space of the secret cinema, which promotes immersion by encouraging audience action within the rules of the production. Similarly, while the ouen-jouei audience also enact any cheering or use of glowsticks within the rules of the ouen-jouei event and cannot influence or change the productions, they become immersed in the story world through these actions.

[6.3] However, as noted above, unlike the story world of immersive theater, which occurs within the shared space of the auditorium, it is impossible to physically integrate the audience and story world of the ouen-jouei movie setting. In fact, secret cinema screenings indicate that screening after exploring a venue may inhibit immersion. As Atkinson and Kennedy (2016, 273) observe, "the very presence of the cinema screen on-site calls to attention the mediation of the spectacle, and underlines the ultimate position of the audience member as spectator as opposed to participant." Therefore, hindered by the physical barrier of the movie screen, immersion in a story world at an ouen-jouei events needs the "high levels of engagement" (Biggin 2017, 271) witnessed in computer gaming. This high level of engagement is similar to a fan's inner experience of fan tourism, which involves feeling a connection between the site (real world) and story worlds despite the impossibility of physically integrating these worlds.

[6.4] Like the fans examined in fan tourism studies, ouen-jouei audiences suspend their disbelief, a suspension assumed to be stronger than in immersive theater, in order to "accept the world of the imagination as real" and "extend their belief in the imaginary beyond the confines of the book or film" (Reijnders 2011, 241). Indeed, some respondents to my survey noted that ouen-jouei events differed from ordinary screenings insofar as they allowed them to "cheer for the movie characters directly" and "express love for the movie characters." Of course, the audiences are cheering for characters in the story world of the film—their support will never reach the characters in the same way as the support of audiences at sports events or plays. Despite such an absolute physical division, ouen-jouei audiences perform as though their cheers reach the characters. Indeed, audiences were observed shouting for an encore at the end of the film (Shinada 2016). These results indicate that ouen-jouei audiences "put their critical, generalized world view aside for the time being, in order to be able to surrender themselves to a particular story" (Reijnders 2011, 241). More specifically, they suspend disbelief in order to immerse themselves in the story world of a film.

[6.5] This study also sought to identify the inner experience of ouen-jouei audiences as they become immersed in a story world. As noted, the audience suspend their disbelief to achieve immersion. However, Bouko (2014, 10–11) notes, "No matter how immersive a performance may aim to be, it will always be possible to maintain one's critical distance, thereby negating the immersion." As such, it may be that the audiences at ouen-jouei events are aware of the boundary between themselves and the film's story world. In answering how ouen-jouei events differ from ordinary screenings, respondents noted, "We feel like we've come to a real concert or live event" and "It is easy to get into a story world while watching a movie [at ouen-jouei]." The survey also asked why respondents had attended multiple ouen-jouei Kinpri showings, with respondents claiming that such events created an "extraordinary space" and replying, "Because it is fun to cheer with glowsticks with the whole theater audience, and we can feel like we're going to a concert." These responses indicate that the audience becomes immersed in the story world at ouen-jouei events while simultaneously maintaining their awareness of their reality in the cinema space. This experience is reflected in the accounts of reporters who participated in ouen-jouei events, with some noting "the illusion of participating in a live music event" (Yomiuri shimbun 2016, 10) and that it felt "like being in a live hall and sharing the experience with other audience members who enjoy the cheering" (Kouno 2019, 5). Such reports reflect the ability of audiences to be both immersed in a story world and to recognize the boundary between that world and the real world (movie theater).

[6.6] In addition, virtual immersion with a projected image can also be experienced at virtual amusement parks, as exemplified by 3D and VR theaters in Japan. At these amusement parks, in the same way as ouen-jouei, audiences sit on their seats, watch images projected on a screen, and immerse themselves as if they are at the bottom of the sea, in the age of the dinosaurs, or at a real concert with hologram virtual idols. However, there are large differences in auditorium equipment and audience performances between ouen-jouei and amusement parks. Most amusement parks have a special large screen or hologram gimmick. In addition, some parks use special techniques and tools such as MX4D, 3D glasses, and VR goggles to direct virtual immersion. Exogenous stimuli from special equipment and tools can also help audiences become immersed. In contrast, as discussed previously, ouen-jouei is held in the same setting as an ordinary film screening, at regular movie theaters, and the audience cannot receive the exogenous stimuli they do at virtual amusement parks. Therefore, to become immersed, ouen-jouei audiences use not only active participation, such as the suspension of disbelief, but also physical performances such as cheering. Thus, immersion at ouen-jouei requires more physical performance from the audience compared to virtual amusement parks.

[6.7] The way in which ouen-jouei audiences interact with the story world of a film can be explained using Ryan's (2002) classification. At ouen-jouei events, the audience becomes immersed in a story world from the internal time and space of the story world, but their exploration cannot impact that virtual world. Accordingly, their inner experience can be classified as "Group 2: Internal-exploratory interactivity" of Ryan's model. However, audience members also recognize that they are in the movie theater in the real world, become immersed and explore the story world from an external time and space, and their exploration cannot influence the story world. Thus, their inner experience can also be classified as "Group 1: External-exploratory interactivity" of Ryan's model.

[6.8] Groups one and two of Ryan's (2002) model correspond with the two modes Reijnders (2011) theorized regarding the internal experiences of Dracula tourists. According to Reijnders, these tourists "use rational terms to describe their desire to make concrete comparisons between imagination and reality" and are "driven by an emotional longing for those two worlds to converge"(233). While Ryan (2002) classifies groups one and two as separate modes, Reijnders (2011) describes these two modes as partially opposing yet mutually dependent in arguing that Dracula tourists adopt both modes in accessing and becoming immersed in a story world. This argument appears to hold for ouen-jouei audiences, who become immersed in a story world while maintaining their awareness of the real world. Although not detailing these two modes, Reijnders (2011) describes this situation in which these two modes exist simultaneously as "transitional space" (Wynants, Vanhoutte, and Bekaert 2008, 161–62)—one in which friction between two perceived realities occurs. This situation is also relevant to the psychological claim that a transitional space is "an intermediate area of experiencing, to which inner reality and external life both contribute" (Winnicott 1953, 90). Wynants, Vanhoutte, and Bekaert (2008, 160) describe the transitional spaces created by performances: "[I]n reconfiguring the different sensorial stimuli, the performance creates a new realm, a transitional space, where the recorded images mingle with the live tactile and aural sensations."

[6.9] In addition, Godwin's (2014) discussion of action figures as transitional objects that can exist within both the real and the story world and Williams's (2020, 141) discussion of ani-embodied characters that offer "a form of 'deviant translation' between text and the corporeal body" both indicate that objects can also create transitional spaces where two worlds exist simultaneously.

[6.10] In the case of ouen-jouei, the performances create a transitional space where the real and the story world exist simultaneously. Bouko (2014, 15–16) describes immersive theater performance as transforming a city into "a hybrid space, at the crossroads between the real and the imaginary" and as emerging from the "inbetweenness" of the real and the imaginary. Similarly, the auditorium at ouen-jouei in the real world becomes "the abstract site" (Williams 2020, 173) that acts as both the real and story world through audiences' performances, such as shaking glowsticks and rooting for characters in the same way that movie characters in Kinpri watch the Prism show. In other words, as is the case with the immersive theater performances, ouen-jouei performances transform the auditorium into a transitional space, a hybrid space at the crossroads between the real and the imaginary.

[6.11] In addition, at ouen-jouei events, the distributor tells the audience, "You are permitted to express excitement as if you are watching a real live performance by cheering etc. at this screening!" (King of Prism: Shiny Seven Stars, February 9, 2019.) Accordingly, "during the singing and dancing scene, the audience were cheering and shaking glowsticks as if they are participating in a live show, and the venue became one" (Lmaga.jp 2016). As seen with the phrase "as if," ouen-jouei audiences believe that they are cheering for the movie characters while recognizing that they are in the theater in the real world. In other words, in the same way that theme park fans know "that these sites are created, that the characters they are meeting are employees in costumes" (Williams 2020, 245), and yet can enjoy immersion in the theme park's story world, ouen-jouei audiences become immersed in a story world while maintaining their awareness of the real world. They negotiate between a sense of themselves as within the story world and in their seats in the real world through their performances. This suggests that "inbetweenness" also emerges at ouen-jouei, allowing the audience to be both immersed in the story world and aware of their reality. Friction occurs between these two perceptions.

[6.12] As is the case with other immersive productions, at ouen-jouei events, "[w]atching performance that appears to be occurring in a separate time (the fictional time and setting of the story world) to the spectator's own time (the real-world time of the performance) is a potential site of negotiation between immersion in the production and in narrative" (Biggin 2017, 143). In other words, ouen-jouei audiences perform within the transitional space between the real and the story world, move between the sense of watching a movie in the real world and the sense of being part of the story world, and have "an opportunity to playfully cross the boundaries between the text and the self and to imaginatively and figuratively travel to the places seen within them" (Williams 2020, 157).

[6.13] Accordingly, the features of immersion in a story world through the audience interaction at an ouen-jouei event are as follows: First, the audience suspends their disbelief in order to become immersed in the physically separated story world through the particular actions encouraged by ouen-jouei events, such as cheering and the use of glowsticks. Second, the inner experience of ouen-jouei audience immersion involves the perpetual negotiation between two modes. In fact, ouen-jouei events include performances without immersion in a story world. For example, when the creators' names—such as the director and distributing agency—are projected on the screen, the ouen-jouei audience calls out, "Thank you!" In this moment, audiences are aware that they are part of a movie theater audience and not part of the story world. During ouen-jouei, the audience moves between the sense of watching a movie in the real world and the sense of being part of the story world, thus experiencing "hybrid subjectivity" (Atkinson and Kennedy 2016, 272).

7. Conclusion

[7.1] This study examined what specific performances are enacted by ouen-jouei audiences to achieve immersion in a story world, as well as the features of this immersion. Based on participation observation, this study demonstrates that audiences achieve immersion through the act of cheering and the use of glowsticks. Analysis reveals two features of the immersion in a story world through the performances characterizing ouen-jouei events: First, audiences suspend disbelief in order to achieve immersion in the physically separated story world. Second, this immersion involves the perpetual negotiation between two modes.

[7.2] This study offers new insight into the more general question of how consumers of media content become immersed in a story world from the perspectives of audience, media, and fan tourism studies. As regards fan tourism studies, this study shows the value of this field's perspectives in audience studies. In other words, this article indicates that cinema audience immersion, in which it is impossible to physically integrate the audience and story world of a movie, can be analyzed alongside the fan's inner experience as examined in fan tourism studies. Moreover, in examining audience immersion through physical performance occurring in a movie theater, this study expands the field of analysis, which has primarily focused on VR and immersive theaters.

[7.3] This study has some limitations. Notably, it does not account for whether these elements exist in other ouen-jouei events and thus fails to clarify whether these characteristics are specific to the Kinpri series. Further research is necessary to resolve this issue, including studies that consider the features of media contents, as well as the complex interaction between fan attributes and the characteristics of physical experience.