1. Introduction

[1.1] Ukrainian scholar Mikhail Sobutsky in 2017 associated a fandom that takes place in a whole other context with the contemporary politics of one's own country:

[1.2] Once upon a time, when series were still a nightly television attraction, not something that you could freely search on the web, the Soviet audience acquainted themselves with them through the British The Forsyte Saga (1967). Of course, this series was based on the canonical text of John Galsworthy, referential to historical reality. The Soviet audience sincerely sympathized with the British involved in the shameful Anglo-Boer War. However, the Soviet audience sympathized with not just Stierlitz, but also with Muller. Serial production played a significant part in the replacement of a specifically Soviet ideology with an abstract imperial one. (my translation)

[1.3] Sobutsky here argues that The Forsyte Saga (which is set from the 1870s to the 1920s) did ideological work by making Soviet audiences sympathize with the British—but the text resonated differently, and in an unintended way, with Soviet audiences than with British ones. The foreign past thus became a canvas for contemporary politics. This sort of work is repeatedly performed in media; often associations that the public bring to the text go beyond the creators' reference, sometimes with political ramifications.

[1.4] A contemporary example is The Last Kingdom (2015–; TLK), a Netflix TV series based on Bernard Cornwell's Saxon Stories, a series of novels published from 2004 to 2020, providing a historical interpretation of the exploits of early Saxon rulers. TLK centers around a fictional depiction of Alfred of Wessex as the first king of the Anglo-Saxons and, in Cornwell's historical interpretation, the creator of England. Both TLK and the Saxon Stories are firmly and authentically grounded in a medieval milieu, but as historical fiction, both include original characters, including the shared main character of Uhtred, who was born a Dane and raised a Saxon, a status that permits the character to do important symbolic and narrative work.

[1.5] This discourse is further extended by fan fiction in TLK fandom, which may freely use both the Netflix series and Cornwell's Saxon Stories as source texts while adding yet another layer of original characters, further research into the era, analyses of existing characters—and, crucially, examinations of the contemporary political scene, with authors paralleling the trauma of the Brexit transition with what King Alfred of Wessex (849–899) wanted to unite by promoting such things as togetherness, solidarity, cooperation, and immigration. In the political moment of the 2019 transition as Britain exits the European Union, it seems inevitable that TLK's Alfred would meet Brexit, as both have large-scale stakes. Fan fiction that comments on politics is a highly effective form of political commentary that accommodates both satire and political wish fulfillment (Ellis 2019), permitting authors to answer speculative and reflective questions about political decisions (Burt 2017). Political fan fiction acts as a sociopolitical barometer measuring the urgent hopes of citizens, their anxieties, and their thoughts (Franke-Ruta 2013). Anti-Brexit fan fiction is one way to measure these hopes and fears.

[1.6] I use two works published in 2019 hashtagged #NotMyBrexit: "One England" by Tumblr user BigHeartBigFart (note 1) and "Under One Kingdom" by Honiejar (note 2). These particular stories were selected because they are representative of the #NotMyBrexit movement in King Alfred fan fic, as well as unique because of their richness in referencing. Although surprisingly similar in their contents, my case studies came from quite different sources, and neither were originally published on the Archive of Our Own (AO3). It is no surprise that most scholarship on fan fiction cites examples from AO3, as it is not only the largest and best-known fan fiction archive but also easy to browse. However, it is important to realize that the fic of AO3 is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to all fan fiction being written. There is much to discover in lesser-known places; for example, on other social media, like Tumblr and Facebook, and more locally oriented equivalents like LiveJournal, on forums dedicated to specific fandoms, and in diaries and letters shared in more private forms of correspondence such as mail groups.

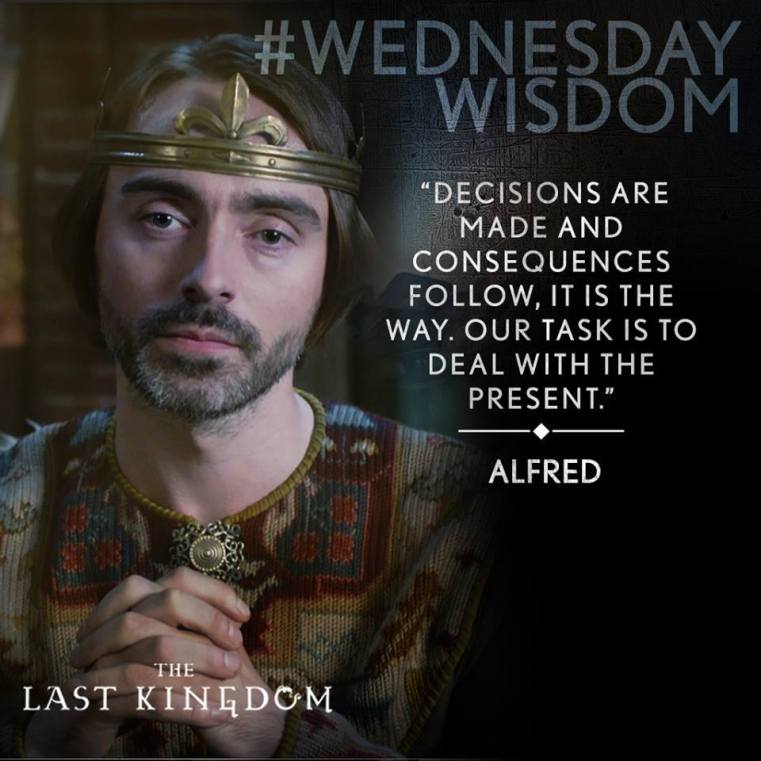

[1.7] Both the works I discuss include quotes from the television series, such as this often-circulated one by King Alfred: "Decisions are made and consequences follow, it is the way. Our task is to deal with the present" (figure 1). But that is by no means the only source of material for these two authors. Their fan fics read as a collage of items from all different contexts that combine to tell a story about how Brexit divides what King Alfred wanted to unite.

Figure 1. King Alfred, "Decisions are made and consequences follow, it is the way. Our task is to deal with the present," in an image often reblogged as a meme.

[1.8] These case studies demonstrate how the authors of TLK fan fiction have added a new layer of fiction by including political quotes and references, arriving at what Judith May Fathallah calls a "pastiche of texts from supposedly different sources" (2017, 195). Fans combine material from their fandom with historical knowledge and today's news channels. By bridging divides between fans and fandoms, between times and places, and between fantasy and reality, these authors express their desire to do away with Brexit and retain a single unified sociopolitical force.

2. "One England" by BigHeartBigFart (2019)

[2.1] Tumblr user BigHeartBigFart's "One England" takes place during the Battle of Edington (878 CE). The fights against the Danes culminated in this legendary battle between King Alfred and Guthrum, leader of the Viking army. This battle is much described; it is included, for example, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a ninth-century collection of annals that served as an inspiration for TLK. One of the main points of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is that it always emphasizes the harmony within the realm of Wessex (Gransden 1975). As Ria Paroubek-Groenewoud (2014) explains, contemporary descriptions of the Battle of Edington are often loaded with religious elements. BigHeartBigFart's story contains them as well; in one scene, Alfred baptizes Guthrum—as if Alfred were a priest, or even Jesus himself. Alfred becomes Guthrum's godfather while the Saxons and the Danes watch. The scene is a meticulous periphrasis of this scene in the Netflix series, with special attention paid to the religious elements.

[2.2] BigHeartBigFart's focus on an evocation of the past is joined by allusions to the present, specifically Brexit. Her story's Guthrum delivers a speech that ends with him telling Alfred, "You have won the war, but you must win the peace; so, now is the time to stiffen the sinews and summon up the blood." The first part of the sentence references a quote by Nigel Farage, leader of the Brexit Party, who declared, quoting Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery: "I've got to see the Brexit process through, we won the war but we must win the peace. I'll see out my time in the European Parliament, so I'll be there until 2019" (quoted in Jefferies 2017). The second half of Guthrum's words to Alfred reference Boris Johnson, a British politician from the Conservative Party, who stated, quoting Shakespeare's King Henry V: "So now is the time to stiffen the sinews and summon up the blood and get on that trusty BAE 146 and go back to Brussels and get it" (quoted in Halpin 2019). That these politicians' quotations themselves contain quotations adds yet another layer of resonance and meaning.

[2.3] The clear focus on #NotMyBrexit is also evident by a lengthy quotation from Ali Smith's Autumn (2016), a novel that overtly discusses the state of the nation, and that is set just after the United Kingdom's referendum to leave the European Union. BigHeartBigFart puts the quotation in the mouth of Uhtred, the Dane who is also a Saxon, who thereby expresses his thoughts about both the Battle of Edington and his own nature and feelings: "All across the country, people felt it was the wrong thing. All across the country, people felt it was the right thing. All across the country, people felt they'd really lost. All across the country, people felt they'd really won. All across the country, people felt they'd done the right thing and other people had done the wrong thing." This ambiguity, setting two camps against each other, is nevertheless undergirded by the understanding that people had done the wrong thing.

[2.4] BigHeartBigFart has Aethelflaed, King Alfred's oldest daughter, take a stand as the voice of reason, but her words are pulled from George Orwell's "The Lion and the Unicorn" (1941), with one important change: "The Anglo-Saxons ['English' in the original] should develop into a nation of philosophers. They will no longer prefer instinct to logic and character to intelligence. But they must get rid of their downright contempt for 'cleverness.' They cannot afford it any longer. They must grow less tolerant of ugliness, and mentally more adventurous. And they must stop despising foreigners." BigHeartBigFart here critiques the pro-Brexit camp, wishing them to change while fantasizing about an Anglo-Saxon reality in which politicians would prefer reason and logic above emotions.

3. "Under One Kingdom" by Honiejar (2019)

[3.1] "Under One Kingdom" by Honiejar provides far more detail in creating a historical milieu than BigHeartBigFart, with classical-language puns and allusions as well as elements and quotes from both Anglo-Saxon texts and from centuries after the life of King Alfred. Like BigHeartBigFart, the texts have a definite anti-Brexit slant, which Honiejar expresses as a longing for unity during a time of political turmoil. The most prominent example in her fic is that of Alfred when he says that he wishes to become a rex pacificus (king of peace, beautiful king) who would rule a united kingdom. But historically, it was not King Alfred but King James (1566–1625) who called himself a rex pacificus, as he was sincerely devoted to peace not just for his three kingdoms—Scotland, England, and Ireland—but for Europe as a united whole (Smuts 2002).

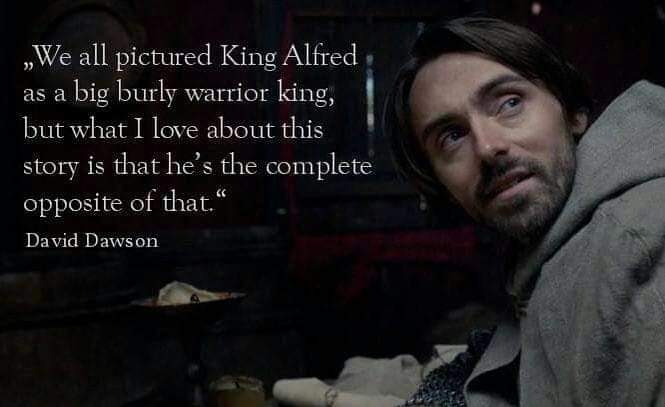

[3.2] "Rex pacificus" was never used historically with King Alfred, but some version of "king of the Anglo-Saxons" was. In his biography of King Alfred (from 893), Welsh monk Asser (d. ca. 909) calls Alfred rex (king) but then rex Angul Saxonum (king of the Anglo-Saxons) (Keynes and Lapidge 1983). This title is similar to that on the Alfred the Great silver offering penny (871–899), AELFRED REX SAXONUM (Alfred, king of the Saxons). As Robert Rouse (2008) explains, Alfred's typological construction as a rex pacificus is based on a much later depiction. The idea of Alfred as a rex pacificus avant la lettre was most likely coined in the eleventh century by William of Malmesbury (ca. 1095 to ca. 1143). His depiction of King Alfred in his Gesta Regum Anglorum (Deeds of the English kings, ca. 1125) was "modelled upon the figure of King Solomon…one of two commonly-used typological biblical kingship types—the other being the warrior" (Rouse 2008, 118). TLK critiques this notion of Alfred as a warrior king. As David Dawson, the actor playing Alfred, supposedly stated in an often reblogged meme, "We all pictured King Alfred as a big burly warrior king, but what I love about this story is that he's the complete opposite of that" (figure 2) (note 3). The "complete opposite" is the TLK portrayal of Alfred as an intellectual and religious king, a wise and maybe even holy man who wants to unite his people and make peace with other peoples. Honiejar likely chose the title "rex pacificus" because this image of King James/King Solomon as a unifying monarch is in line with the depiction of King Alfred in TLK: a king whose political beliefs are diametrically opposed to the principles of Brexit.

Figure 2. King Alfred, "We all pictured King Alfred as a big burly warrior king, but what I love about this story is that he's the complete opposite of that," in an image often reblogged as a meme.

[3.3] Another hint at Honiejar's historical interests can be found in a scene when Alfred speaks of the strategies he has read about: "The intellectuals claimed that warriors from the outside networks were assimilated into the current armies and strengthen them. Each of the conquered people contributed to the while [sic]." He even mentions a name: Appian.

[3.4] A man of great qualities, truly. Perhaps it was the virtues of prudence, proficiency, patience and hard labor but it was more than that. Beyond each, each of the conquered's ability for cultural superiority, political matureness, and economical abilities…it was the fact that the integration of all defined and stabilized their Empire. I want that, do you understand?

[3.5] All the virtues mentioned are exemplary for early Rome and are often described by their Greek equivalents (εύβουλία, άρετή, φερεπονία, ταλαιπωρία)—for example, unsurprisingly, by Appian. Appian of Alexandria (ca. 95 CE to ca. 165 CE), a Greek historian living in Rome, described the Roman Empire as the largest, most powerful, and most stable civilization ever (1913). By having King Alfred name Appian as an inspiration, Honiejar suggests that the Roman Empire's stability is a great example for Great Britain, clearly staking out an anti-Brexit stance.

[3.6] Honiejar's anti-Brexit stance narrows to allude to the fate of academics in a post-Brexit world. With the Brexit-imposed lack of freedom of borderless movement, as well as an anti-immigrant focus, during the transition, academics felt particularly singled out and unwelcome in the United Kingdom. Honiejar approvingly parallels the Roman mode of education, with its Greek intellectuals (Syme 1959; Dhesi 2015), with those championed by King Alfred, who sought out intellectuals from other lands who would help institute education reforms in his kingdom. King Alfred tried to revive education in the kingdom, as education would confer a sense of united and ordered history that would cause the fractured English populations to unite under the threat of Viking campaigns (Plummer 1902; Keynes and Lapidge 1983; Lendinara 1991; Yorke 1999). "Under One Kingdom," the very title of which indicates the author's slant, uses these parallel tracks of education reform relying on unity and cooperation to argue for a similar take today: a repudiation of Brexit.

4. Conclusions

[4.1] As these TLK fan fics indicate, fans imagine a unified Great Britain that parallels their desire to maintain a unified European Union, with the setup of TLK particularly suited to their #NotMyBrexit arguments. "One England" by BigHeartBigFart and "Under One Kingdom" by Honiejar both focus on Alfred of Wessex, the most famous Anglo-Saxon king who is today remembered as a scholar, translator, and patron of education. Whereas BigHeartBigFart also writes about Alfred as a successful warrior, Honiejar focuses on Alfredian education reform, comparing the educational program instituted by King Alfred and the system of classical education in Rome, both of which focus on using education to create a national identity. Both authors play with quotes, references, and associations, both present and historical, to express their views about the political situation in Great Britain in the year 2019.