1. "This was a triumph/I'm making a note here, huge success"

[1.1] Since its first airing, the CW series Supernatural (2005–) has attracted fans in droves. These fans actively produce scores of fiction, art, and music videos (vids) relating to the adventures of brothers Sam and Dean Winchester as they fight monsters and demons across the United States. I rather blissfully followed the series through its opening seasons and enjoyed reading fan fiction and watching action vids about "the boys." However, despite all the fannish passion for this text, all is not well in Supernatural fandom.

[1.2] I was not aware of these conflicts until I saw the now renowned vid "Women's Work" by Luminosity and Sisabet (August 15, 2007) for the first time. It so clearly deconstructs the representations of women throughout the source material and highlights the series' (mis)treatment of its female characters that suddenly I was watching Supernatural in a whole new light, and one that was not necessarily favorable. During season 3, in particular, I struggled with my newfound relationship with the source material after watching what has become the most controversial episode, 3.09 "Malleus Maleficarum." I sought out episode reviews on LiveJournal for the first time to see if other fans shared my reactions and discovered a maelstrom of negative commentary: not only were fans incensed with the series and its writers, but they were also arguing with each other.

[1.3] For the purposes of this essay, I will seek to unpack and reflect on the layers of context, conflict, and meaning within a particular critique of Supernatural and its fandom: Counteragent's meta vid "Still Alive" (October 19, 2008). This vid directly confronts the clashes among the fans with what the vidder has called a bit of "well-meant self-criticism" (personal communication, September 2, 2009). Using a tongue-in-cheek style, "Still Alive" addresses the online fandom on LiveJournal and the fannish reactions to season 3 of Supernatural, reactions I stumbled across rather unwittingly in early 2008.

Vid 1. "Still Alive" (2008) by Counteragent.

[1.4] According to Counteragent: "Season Three was accompanied by a lot of posts in fandom about misogyny in Supernatural. Some of them were well thought out (on both sides of the debate) and some were full of…women being mean to other women" (personal communication, September 2, 2009).

[1.5] In particular, the vid uses footage from the aforementioned controversial episode 3.09 "Malleus Maleficarum," which was thought by fans to represent the pinnacle of Supernatural's misogynistic representation of women. In order to fully engage with the vid, some context is useful here. The title of the episode comes from the infamous medieval handbook from the Inquisition, which describes how to discover and convict witches and makes a special case as to why women, rather than men, were more likely to be susceptible to the forces of the devil due to their carnal natures (note 1). In the episode, Sam and Dean discover a coven of witches who have been using their powers to improve their lives, until they begin to turn on one another. Fans found this episode to have an overpoweringly negative view of all the female characters and were extremely put off by the repeated use of the word bitch; many (myself included) were deeply unnerved by the revelation that Ruby was a witch herself, reducing this powerful female character to just another "lying whore." A review of the episode by deadbeat-nymph, one of the first I stumbled across while searching for fans' responses, is worth quoting at some length:

[1.6]Our Dean. We know he loves pussy, but that shouldn't preclude loving women. I guess my interpretation of Dean was one in which both were true—I never felt that he looked down upon, reviled, or scapegoated upon women. But now? Now he wants to burn the witches. And plunge a twisted blade into a possessed woman's back, over and over again with shocking vehemence. Plunge his sword into the depths of her insides. Bad porn turned literal. And Ruby, who threatens with her spiritual power and knowledge, is a skank. And a bitch, bitch, bitch, bitch, bitch—how many times did he say it? …Dear Show, You cannot make of Sam and Dean Inquisitors and still have us love them. Your audience is primarily female. You don't value us as viewers, we know, you want male viewers, whose eyes are apparently more valuable than ours, we know. (February 1, 2008)

[1.7] Many other fans found the episode similarly disturbing, but there were also many posts that sought to explain the supposed misogyny in the context of the show. Factions developed within the LiveJournal community around different points: some argued that fans shouldn't read too much into it. Others commented that the negativity toward these witches was due to their demonic nature, not their gender, and therefore the charges of misogyny were unfounded (note 2). Critics and apologists clashed, and the debate spiraled out of control until there was a great deal of bad blood circulating around the community. "But," wrote Counteragent, "I couldn't help pointing out that some of the fights in fandom about misogyny are scarier than what is on the screen" (October 19, 2008).

2. "We do what we must because we can/For the good of all of us/Except the ones who are dead"

[2.1] The vid itself opens with shots of the different female characters in the series, representing the fans. Embodying competing opinions, Meg and Ruby argue whether season 3 "sucked" or "rocked," with their position represented in the form of a LiveJournal username.

Figures 1 and 2. Meg and Ruby offer their interpretations of season 3. [View larger image of figure 1.] [View larger image of figure 2.]

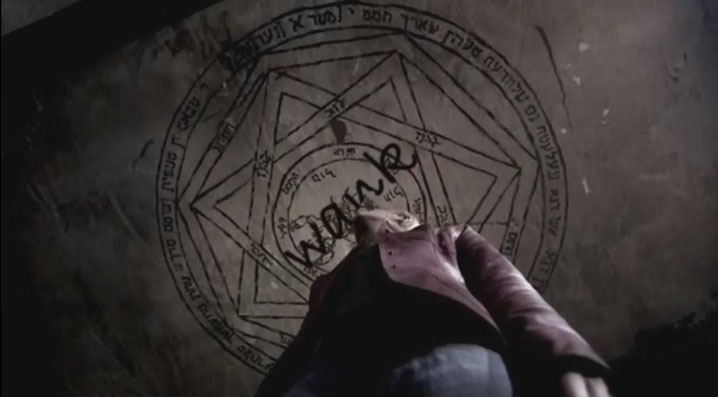

[2.2] The season 3 debate is at first argued politely between these character/fans, each stating their own opinions, until the discussion collapses into "wank." The fan-written wiki Fanlore.org defines wank in fandom in three ways: as a "loud or public online argument," a "catchall term for objectionable or contemptible fannish behaviour," and/or as "elaborate canon-rationalisation or theorizing" (http://fanlore.org/wiki/Wank). Utilizing the visual shorthand of the devil's trap from the series mythology, the vid shows these female fans trapped by their own endless, wanky debates.

Figure 3. A female fan is unable to escape from a "Wank Trap." [View larger image.]

3. "I'm not even angry/I'm being so sincere right now"

[3.1] The fans are represented as the malicious witches from "Malleus Maleficarum" who were so criticized: as in the episode, these women begin by working together to create great fan works. The fans cooperate and enjoy the fruits of their labor, but ultimately they turn against each other with deadly results: the fans are just as guilty of mistreating other women as the characters they malign.

Figures 4 and 5. The fans work together in LiveJournal communities (like SPN_multimedia) at first, before some members become victims of the virulent debates. [View larger image of figure 4.] [View larger image of figure 5.]

[3.2] Again and again the fans argue and reconcile. The intrafannish anger of the witches in the previous shots of the vids is resolved, at least temporarily. But a new debate sparks off the anger once again. The rage is so consuming that the fans are here represented by demon characters from the Supernatural canon: powerful and violent, their eyes turn black as they summon their power and attack each other yet again.

Figure 6. The female fans of Supernatural brutally debate the series. [View larger image.]

4. "But I'm glad I got burned, think of all the things we learned/For the people who are still alive"

[4.1] However, all is not lost: "Debates on canon missteps aren't always wanky. Sometimes they are the impetus for brilliant art-commentary," explains Counteragent (personal communication, September 2, 2009). The debates about misogyny have actually inspired some detailed examinations of the canon material, with "Women's Work" as just one example (note 3). "Still Alive" showcases not only the fans who make up the Supernatural fandom as a whole, but it also contains a level of textual criticism. As with "Women's Work," by using episodes that were seen as particularly misogynistic by the fans, "Still Alive" offers up Supernatural's treatment of its female characters for analysis. For example, recurring images of women in white dresses and of supremely feminine demonic little girls appear alongside criticism of such tropes. Shots from "Women's Work" also appear in the vid as part of the larger fannish conversation. The clips from "Women's Work" (which also uses clips from Supernatural) are made visually separate from Counteragent's use of the footage by first showing an article from New York Magazine (http://nymag.com/movies/features/videos/40622) that discusses the vid, and then the clips are centralized in the frame and made smaller in order to be visually distinct. While the title of "Women's Work" is briefly visible, the viewer must be extremely familiar with Supernatural, vidding, and online fandom in order to separate all these shots and their contexts.

[4.2] Next, the vid shifts its focus as the faces of the character/fans spin and blur into an audience of fans at a Supernatural convention, turning to examine the more positive elements of fandom: namely, its creativity.

Figure 7. The fans and characters of Supernatural blur together. [View larger image.]

[4.3] The character/fans welcome the Winchester brothers into their lives, and use the raw material of Supernatural to delve into the elements of the story the television text has not: minor characters are given back stories, relationships are explored, and crossovers developed. The vid increases its pace, and shots of the diverse comics, novels, LiveJournal communities, art, games, and vids swirl across the screen, paying tribute to all the talent the vidder has discovered through fandom, despite the wank. The vid ends optimistically, with the refrain "I will be still alive": no matter what happens, the fans will persist. The final shot is of the character/fan Ruby giving the Winchesters a cheeky grin.

Figure 8. Ruby lets the Winchesters know she will be "still alive." [View larger image.]

[4.4] In addition, a contextualization of the selected song, "Still Alive," is helpful in our reading of the vid. The piece was composed by geek musician Jonathan Coulton for the popular videogame Portal (released in 2007). The song appears in the final credits after the game has been completed, and is sung in the persona of the fan-favorite character of GLaDOs. Familiarity with the source context of this song adds another layer of meaning to this vid for the viewer: GLaDOs, voiced by Ellen McLain (who also performs the song) is an increasingly passive-aggressive artificial intelligence that initially assists the player, and ultimately must be destroyed in the final level of the game. Despite the apparent death of GLaDOs, the game ends with this song, the lyrics of which suggest that GLaDOs is indeed "still alive" (note 4). The evolution of the character of GLaDOs, from friendly to ambiguous to antagonistic, parallels the evolution of the fannish arguments. And just as it seems as though "she" (note the feminine gender here) has been defeated, GLaDOs reminds us that she hasn't gone anywhere. Thus, the resilience of fans to survive despite their destructive battles is emphasized through the use of this song, but so is the potential for it all to happen again.

5. "I will be still alive"

[5.1] Throughout the vid, Counteragent creates multiple layers of commentary that require an in-depth knowledge of Supernatural, its fandom, and the associated LiveJournal communities. I have attempted to provide sufficient contextual information for this vid to be read by a wider audience, but this vid will always be meant for a very specific audience at a very specific time in this fandom's history. It is also interesting to consider that while it is these female character/fans who form the bulk of the first section of the vid, this is also the portion that is extremely critical of fandom. The celebratory second half of the vid, meanwhile, focuses almost entirely on the brothers. Certain characters like Jo and Cassie are taken up in fandom as seen in the vid, but as Counteragent pointed out to me, "There is a recurring theme in SPN fandom of [the fans] not liking female characters, stars, or actors' girlfriends" (personal communication, September 2, 2009). The final, uplifting montage in the vid features fan works solely dedicated to Sam and Dean. While the fans lament the treatment of women in the show, it is these male characters who are seen to be most worthy of their attention (and indeed, who are the most well-developed in the source material). In the end, Supernatural is a show about "the boys," and this focus is reflected in the fan works.

[5.2] While fandom usually celebrates multiple perspectives and interpretations in fan fiction, vidding, and other fan works, I was surprised at how violently dissenting opinions were put down in this battle over season 3. In this vid, I can see myself and my fellow fans, participants in fandom and viewers of Supernatural, implicated in propagating these tensions. Each time I watch an episode of the series I am infinitely more aware of the problematic nature of the text and my engagement with it. While I was uplifted by the montage of astounding fan works, this vid also left me profoundly unsettled as I recognized my own participation in similar "wanky" arguments. As I understand it, "Still Alive" reaches out to ask its audience to respect the diversity of subject positions that are usually so cherished in fandom. Hopefully, we can maintain our good humor and be "still alive," despite it all.

6. Acknowledgments

[6.1] Grateful thanks go out to Counteragent for her permission to use her vid and online comments, and for her candor and enthusiasm. Thanks also to PK, GB, AW, CM, BW, and JV for their comments on the early drafts of this piece. This research has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong.