1. Introduction

[1.1] Shortly after creating a Tumblr entitled everydirectiondrag in late 2013, a group of drag kings called Every Direction posted a video of their first performance. When played, the video reveals a dimly lit stage framed by glittering, beaded curtains; the post's caption reveals this to be the Oakland bar known as the White Horse Inn, one of the oldest continuously running gay bars in the United States (Every Direction Drag 2013). Filmed in October 2013, the video depicts the group of drag king performers—defined by Del LaGrace Volcano and Jack Halberstam (1999) as those who make masculinity into an act—being welcomed onto the stage for the first time. One by one, the performers known as Ben Downthere, Robin Dick, Cherii Poppins, Jake Mioff, and 7 Minutes in Evan enter the frame, taking their places on the stage as Oakland's premiere drag king boi band: Every Direction.

[1.2] As the first notes of One Direction's infectious 2012 hit "I Would" begin to play, the bois line up and gently bop from side-to-side in matching cardigans and thick-rimmed glasses. Jake Mioff moves to the front of the stage, assuming the role of One Direction's Liam Payne while mouthing the song's opening lines: "Lately I found myself thinking / Been dreaming about you a lot / And up in my head I'm your boyfriend / But that's one thing you've already got." He pantomimes tears as his verses come to an end, and he returns to the group's lineup. Each boi takes his subsequent turn in the spotlight as the song progresses, with Robin Dick delivering Niall Horan's iconic line, in which a daydream about kissing the object of one's affection becomes a crushing return to the real world: "Reality ruined my life."

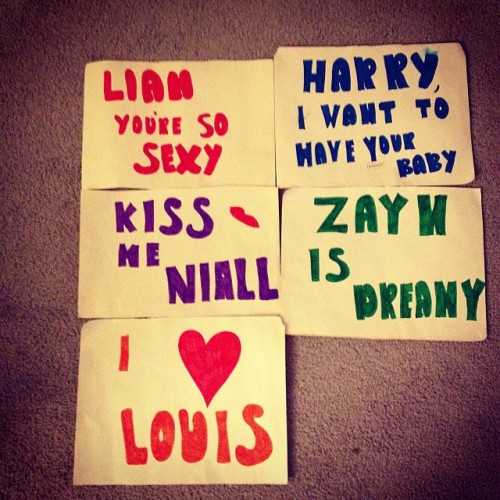

[1.3] The song culminates in a series of choruses, punctuated by an insistent set of questions: "Would he please you? / Would he kiss you? / Would he treat you like I would?" At this, the bois collectively lift their shirts to reveal stomachs painted with the letters L-O-V-E and a heart symbol, each moving closer toward the camera and into the audience as hands reach out to touch their exposed skin. After collectively freezing in place for the song's last verse, the bois return to life as the beat drops, leaping off the stage and into the crowd for a rousing final chorus wherein they jump, clap, and spin their way to a final formation that famed '80s boy band New Kids on the Block would have been proud of, with each boi striking a unique signature pose. No longer performance virgins, they exit the stage, and the clip ends with the sound of thundering applause. Subsequent posts reveal handmade signs that were held by fans in the audience that night (figure 1), along with an endorsement by Autostraddle, a popular website for lesbian, bisexual, and queer women.

Figure 1. Signs held by fans during an Every Direction performance at the White Horse Inn. Photograph from the Every Direction Tumblr page.

[1.4] That Every Direction's members are not only enthusiastic performers but also avid fans of One Direction (henceforth 1D) is evident from the content of their Tumblr. The group's Tumblr was active from October 2013 to February 2015; during that time, photographs, gifs, and fan art featuring the boy band appeared on Every Direction's blog as frequently as posts promoting Every Direction's own performances. Every Direction also openly acknowledges the extent to which Tumblr fandom of 1D inspired their formation; many of the group's members began as 1D fans on Tumblr. Every Direction was particularly inspired by 1D's queer fandom on Tumblr, and the group's performances represent one of the most publicly visible manifestations of the thousands of lesbian fan works produced on the platform between 2012 and 2016.

[1.5] Tumblr's status as the primary digital home for 1D fandom, coupled with its massive popularity among LGBT youth, made it the central gathering place for many lesbian and queer fans of 1D. Furthermore, Tumblr's public structure familiarized a wide range of diverse fans—both queer identified and not—with queer reading practices and lesbian cultural spaces. I will analyze the crucial role that Tumblr played in fostering lesbian fandom of 1D, using lesbian rereadings and reimaginings of 1D circulated by fans on the platform to explore the many and varied manifestations of queer joy, obsession, and self-articulation that the platform enabled. In doing so, I show how lesbian 1D fandom both draws upon and resists lesbian feminist political legacies.

2. Methodology

[2.1] My data for this article consist of Tumblr posts related to 1D fandom and interviews with members of the drag king performance group Every Direction. From approximately June 2015 to October 2016, I engaged in observational research of 1D fandom on Tumblr, paying particularly close attention to lesbian and other queer women's 1D fandom. I received permission to reference the Tumblr posts that appear in this article. Although I refer throughout this article to lesbian 1D fandom, this is not a commentary on the sexual orientation of any of these Tumblr posts' authors, about whom no personal information was collected.

[2.2] As part of my research, I also interviewed four members of the drag king performance group Every Direction. I became aware of Every Direction during my observational research; the group was located in California's Bay Area, but at one point they also had active Tumblr, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube accounts. I was granted institutional review board approval for these interviews by the University of California–Irvine Office of Research in September 2016. All interviewees are adults, and an informed consent form disclosing the nature of my research was distributed before each interview. The interviewees were informed that their names would be used in future writing associated with these interviews because the group members' names had been publicly associated with Every Direction prior to my research. Every Direction's group members identify in a variety of ways; not all of them are lesbians, or women, as Jae Basiliere (2019) has noted is common for drag kings. Nevertheless, like Basiliere, I argue that the group is in conversation with lesbian culture regardless of the group members' individual sexual and gender identities.

3. One Direction's digital breakthrough

[3.1] Popular discourse often frames 1D as one of the pop music machine's most artificial products, in part because the group did not form organically. Rather, all its teenaged members auditioned as individual acts for the British singing competition show The X-Factor, and they were subsequently grouped together by judge Simon Cowell. Though the boys placed third in the singing competition, 1D was a hit with young women, who comprise a large portion of the show's audience demographic (Barnes 2010). Shortly after being voted off the show, the band was signed to Syco Records. Their first studio album, Up All Night, was released in early 2012 and became a massive global success, the first debut album by a British band to enter the US charts at number one (Fitzmaurice 2012). Buoyed by the huge amount of enthusiasm expressed by fans on social media, the boys embarked on their first headlining concert tour in the United Kingdom in late 2011. The group went on to release four more chart-topping studio albums, headline many more sold-out tours, and become the subject of a successful 2013 documentary by Morgan Spurlock (One Direction: This Is Us) before finally disbanding in 2016.

[3.2] Less visible to the public at large than the band's music, touring, and official merchandise was the vast, active fan base that took shape around them on various social media platforms, especially on Tumblr. Tumblr served as a primary hub for 1D's fans from early in the band's career, and the boy band's popularity on the platform remained high even as their broader public appeal began to wane from 2015 to 2016. There are many reasons why the platform was ideal for 1D fandom. As critics have pointed out, the boy band had a uniquely "chaotic" appeal (Tiffany 2016), with the boys wearing artfully mismatched outfits and engaging in light roughhousing. As a platform, Tumblr was uniquely suited to accommodate this chaos; its multimedia interface could allow fans to use a single platform to circulate videos, gifs, photos, and text-based posts about the band, and its infinite scrolling dash acted as a constant content generator for a worldwide fandom that was active 24/7 (Stein 2016).

[3.3] Although 1D's youthful antics certainly made them easily gif-able, I argue that the group's success on Tumblr had much more to do with the platform's ability to accommodate fans' particular needs and desires, particularly those of queer fans, than it did with the boys themselves. The avid use of Tumblr by 1D fans to not only consume but also create media for other fans helped 1D retain its popularity on the platform for more than a year into the group's hiatus. According to Tumblr's own metrics, 1D was the platform's second most reblogged band for the year 2015, and "Larry Stylinson"—the name given to the imaginary romantic relationship between Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson—was Tumblr's most reblogged ship (Falcone 2015). In 2016, a year into their hiatus, 1D was still Tumblr's third most popular fan fiction topic, as well as the third most popular band on the platform (Tiffany 2016).

[3.4] Directioners also valued Tumblr because they regarded it as a more private space than other social media. Fans' perception of Tumblr's status as the home for true 1D fans is tied to the anonymity that the platform offers its users. Unfettered by the judgment of their families and peers, who might mock their love for the band, fans took to Tumblr to express their unfiltered thoughts, opinions, and desires. In her analysis of the Larry Stylinson phenomenon, Daisy Asquith notes that many Directioners considered "Tumblr to be an almost sacred space, in which the Larry fandom can be private" (2016, 87). This notion of privacy comes up often in fans' explanations of their preference for Tumblr; the inscrutable logic by which the platform operates is thought to keep out older siblings, parents, and anyone else who would mock Directioners' love for the band.

[3.5] Alexander Cho's (2018) work has shown that this privacy is particularly important to queer youth of color, many of whom prefer Tumblr over other, more public social media platforms such as Facebook. Ksenia Korobkova's study of identity formation in 1D fandom also emphasized Tumblr's relative privacy, with one of her informants praising the platform "for having a logic that is harder for adults to crack and thus less likely to be invaded by adults, unlike Facebook" (2014, 31). Storyboard, Tumblr's short-lived news blog, asserted that Directioners use the platform like "a kind of naively secret journal, a place to document it all, in company with other people who understand" (Bennett 2012).

[3.6] This language of privacy and no-adults-allowed policies recalls Jenny Garber and Angela McRobbie's seminal 1977 identification of girls' bedrooms as important subcultural spaces that often revolve around the consumption of popular culture. Tumblr's relative privacy from parents places it within this tradition and made it appealing to Directioners looking for a virtual home. For lesbian fans of 1D, such private spaces were especially important; like so many other LGBTQ youth from this period, they congregated on Tumblr. Several studies of young people's media preferences in the mid-2010s found that LGBTQ youth were more likely to use Tumblr regularly (Byron et al. 2019). As a result, Tumblr became an outlet for the expression of lesbian Directioners' queer identifications and desire, challenging the heteronormative depictions of girl-fans that have long characterized the writing about boy bands.

[3.7] Although there is little scholarly work on 1D fandom in particular, scholars working in the fields of fan studies and musicology have explored the relationship between queerness and girls' boy band fandom. Fan studies scholars have written extensively about "popslash," a subgenre of RPF (real person fiction, or fan fiction written about real people) focusing primarily on boy band members, that sprung up on writing-focused social media platforms such as LiveJournal during the early aughts. In her work on RPF and the performance of queerness on LiveJournal, Kristina Busse (2006, 216) analyzed the ways in which fans "write their RPS characters as addressing issues of identity construction and performativity, and in so doing, they deal with their own identities, relationships, and desires." Although the majority of 1D's fans opted for video- and audio-centric platforms like Tumblr over writing-oriented ones like LiveJournal, Directioners continued this tradition of using fan works to construct their own identities and communities.

[3.8] Musicologists have also addressed the queer potential of girls' boy band fandom. In her 2016 study of lesbian fans of male pop idols, scholar Barbara Brickman updated Garber and McRobbie's work by complicating heteronormative readings of "what girls do in their bedrooms" (2014, 447). She demonstrated how male pop idols in particular enable homoerotic interactions between female fans, drawing attention to "the fan's consumption of a sign of female masculinity and lesbian erotic potential in the figure of male pop star" (Brickman 2014, 444). The blurring of gender lines by 1D—the "girlish masculinity" (Wald 2002) so common to male pop idols— was marked by their youthful, androgynous appearance and boyish sartorial preferences, which gave them enormous lesbian aesthetic and erotic appeal. Tumblr's 1D fandom provided a multitude of digital evidence of how this lesbian aesthetic sensibility and "erotic potential" was incorporated into fans' processes of individual and collective identity formation, highlighting the boy band's relevance to both lesbian identified fans and a broader lesbian community. The group Every Direction is one such example, as they drew from both Tumblr-based 1D fandom and lesbian performance traditions to articulate a queer and lesbian interpretation of the boy band's appeal.

4. Feminist values, queer desires: The politics of lesbian fandom

[4.1] As a performance group, Every Direction follows in the well-established footsteps of the many drag kings that came before them. While they have never achieved the kind of fame or notoriety accorded to drag queens, drag kings have proliferated in urban hubs as both group and solo acts for decades, reaching their heyday in the 1990s. Groups of drag kings have also previously performed as boy bands; the Backdoor Boys, referenced by Jack Halberstam in his book A Queer Time and Place (2005), are one notable example. What Every Direction's unique performance aesthetic highlights is the fannish sincerity that characterizes lesbians' relationship to boy bands. The love and intimacy with which the routine is crafted, the evident earnestness with which it is acted out, reveal something beyond a desire for the boy band to be "taken back from the realm of popular culture and revealed as proper to the subcultural space" (Halberstam 2005, 178). Rather, Every Direction's performances and Tumblr presence highlight the limitations of the subculture versus popular culture binary.

[4.2] Instead of crafting a camp performance that attempts to extract boy bands from the realm of popular culture to insert them into a lesbian subcultural canon, Every Direction's performance of fandom brings the boy band into conversation with lesbian culture and identity, recalling the historical affinity that has existed for decades between lesbians and young, male heartthrobs from James Dean to Justin Bieber (Brickman 2014). Indeed, rather than existing as a kind of counterpoint to Directioners' love for the band, Every Direction's performance and Tumblr persona reveals that lesbian fandom is inseparable from the popular cultural realm. The group's Tumblr juxtaposes photographs of drag performances and posts from other queer 1D fans with photographs and gifs of the 1D boys singing, dancing, and horsing around, challenging the neat separation of subculture and popular culture that pervades academic discussions of lesbian fandom.

[4.3] This merging of lesbian subculture and mainstream popular culture does more than just challenge conventional wisdom about the boy band's heterosexual appeal. Lesbian 1D fandom also resists the exclusive association of lesbians with the subcultural. Brickman (2014) describes this phenomenon in her work on lesbian fandom of Morrissey, writing that although much academic writing recognizes lesbians as engaged fans of other forms of popular culture, lesbians are almost never identified as fans of popular music. Furthermore, when queer critics do discuss lesbian music fandom, "adoration of pop music becomes an unwelcome or less pressing concern than fandom directly tied to subcultural practices, feminist values, and identity politics" (Brickman 2014, 446).

[4.4] The notion that lesbians have a general preference for music with lesbian and queer subcultural affiliations can be traced back to the legacy of the Women's Music Movement of the 1970s. During this era, lesbian feminists attempted to create a musical genre and industry powered solely by women, hoping to give women an alternative to the male-driven popular music industry. Although early definitions of women's music often described it as music created by, for, and about women, such definitions failed to address the reality that women's music was specifically lesbian music. Although the movement was rife with internal conflict and ultimately failed to remain financially solvent, its impact on lesbian music is still felt today. The fusion of lesbian identity, politics, and musical genre that characterized the Women's Music Movement continues to shape assumptions about lesbian musicians and fans within the music industry, underscoring the belief that lesbian fandom primarily coheres around music that is both political and subcultural. Rather than generatively tracing a feminist lineage for contemporary lesbian and queer women's music listening practices, this exclusive association between lesbians and subcultural music often replicates lesbian feminist political prescriptivism, suggesting that lesbian fans of mainstream popular music have failed to achieve political purity.

[4.5] For the women involved in making and promoting women's music, it was important that listeners' reception of that music was shaped by the same lesbian feminist ideology that the movement espoused. Musicologist Jodie Taylor notes that early women's music was influenced by the stylings of folk music, which "was already imbued with leftist and egalitarian political themes, and less bound to the rigid gender roles ascribed to rock and pop" (2008, 41). Women's musicians also shared many folk musicians' desire to collapse the distinction between audience and performer, fan and celebrity (Frith 1996): the movement discouraged women from thinking of its most well-known performers as stars, and many lesbian feminist publications (Graetz 1982) suggested that the star–fan dynamic itself replicated the oppressive power dynamics inherent in heterosexual relationships. When viewed using this analysis of fandom's power dynamics, boy bands appear to be a particularly insidious method of channeling girls' energies toward boys, reinforcing their ultimate subservience in a gendered power dyad. However, this opposition to fandom and star-worship misses the ways in which the fan exercises a power of her own.

[4.6] Lesbian 1D fandom variously turned the boys of 1D into butch icons, lesbians in love, and fodder for queer-girl fantasies. Rather than indoctrinating girls into heteropatriarchal ways of relating to both men and one another, 1D fandom was an opportunity for lesbian fans to exert control over the text of the boy band, with fans often shaping it into something else entirely. In her essay "Sexing Elvis," Sue Wise (1990) analyzes a similar phenomenon in women's fandom of Elvis. During the 1970s, Wise says, the feminist party line was that "'Elvis' consisted of a social phenomenon and personal image which downgraded women by elevating the male macho hero to unprecedented heights" (336). Wise turns this interpretation on its head, suggesting that such feminist dismissals of Elvis fandom are actually rooted in male critics' interpretations of the phenomenon. Faced with masses of screaming, "out of control" women and girls at Elvis concerts, male music writers concluded that Elvis was the one in control. Wise wrote, "By turning Elvis from what in effect he was—an object of his fans—into a subject, the girls' behavior was de-threatened and controlled" (1990, 338). By reclaiming boy band fandom as a space where girls exercise control rather than abandoning it, lesbian 1D fans resist misogynist interpretations of girls' fandom.

[4.7] Although lesbian 1D fandom retains some key elements of lesbian feminist politics and culture, this reinterpretation of the boy band phenomenon also has much in common with the poststructuralist analysis of gender, sexuality, and power that began to dominate lesbian and queer communities in the 1980s and 1990s. Sociologist Arlene Stein (1997) described how, spurred on by both the rise of poststructuralism in the American academy and the challenges to lesbian feminist political dogma posed by lesbians of color and trans women, many lesbians during this time period "shifted lesbian politics away from its focus upon the 'male threat' and toward a more diffuse notion of power and resistance" (215). While a separate "women's culture" was often framed as the solution to patriarchal mass culture by lesbian feminists seeking to empower women and build community, women of color had long pointed out that this same women's culture remained rooted in racism and misogyny.

[4.8] As the 1980s progressed, many lesbians embraced the notion that there was no such unproblematic space separate from popular culture, opening the door to more ironic and playful forms of cultural consumption. Lesbian 1D fandom shares the more diffuse conception of power that undergirded this shift. However, while this revised relationship to popular culture is a clear precursor to lesbian 1D fandom, this fandom also retains some critical elements of lesbian feminist culture and politics: a trenchant critique of heteropatriarchy in popular culture, the creation and circulation of lesbian media, and the establishment of an affirming lesbian and queer women's culture.

5. "I would": Creating lesbian culture on Tumblr

[5.1] Though queer women existed both within and alongside a larger 1D fan community that had a vast, powerful presence on Tumblr, little to nothing has been said about them in media coverage of the band's fan base. In the absence of mainstream recognition of their existence, queer women use Tumblr to cultivate fan communities through multiple practices, sharing queer-specific fan texts, artwork, and personal confessions that cannot circulate as easily on other social media platforms. Tumblr user jack-nought's post proclaiming, "one direction really is lesbian culture wow" (2017) is representative of an entire genre of lesbian 1D content production on Tumblr, in which users repeatedly assert the group's cultural significance for lesbians.

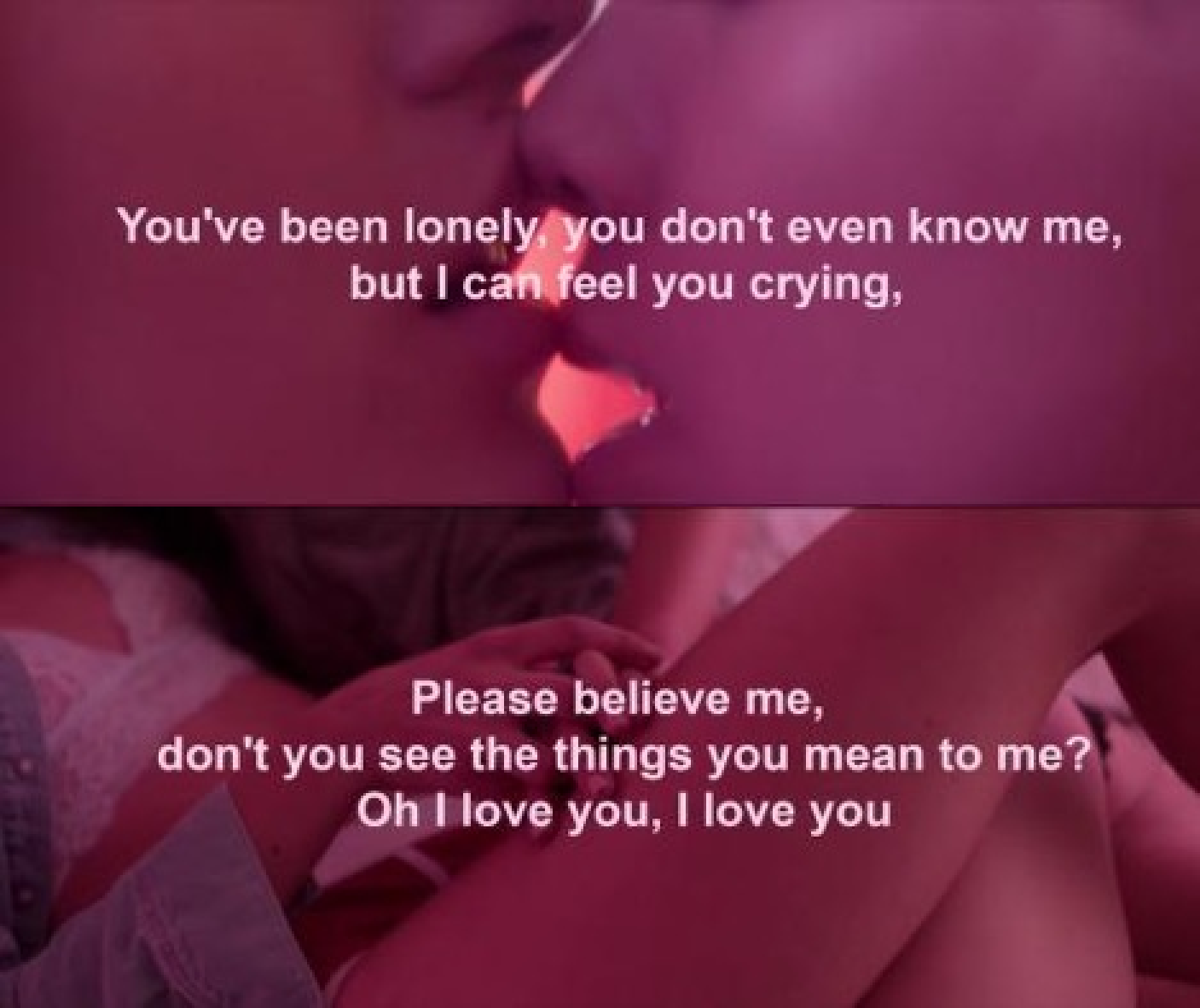

[5.2] Lesbian Directioners also frequently post images and videos that combine 1D's lyrics and/or music with visuals pulled from movies or music videos featuring queer women. One set of images, created by Tumblr user poweredbynew (2015), features photographs of two women kissing, limbs entwined, overlaid by lyrics from two popular 1D songs (figure 2). The pastel pink images, taken from the music video for pop singer Hayley Kiyoko's 2015 single "Cliff's Edge," are combined with the love-struck lyrics of 1D songs "Diana" and "Olivia," evoking the visual aesthetic of Jamie Babbit's lesbian camp classic film, But I'm a Cheerleader (1999). Posts like these demonstrate the extent to which 1D fandom facilitated the formation of community and sexual identity for lesbian fans; through the consumption and remixing of these images and texts, lesbian fans were able to connect with each other and conceptualize their own identities.

Figure 2. Stills from Hayley Kiyoko's music video for her single "Cliff's Edge," featuring lyrics from the 1D songs "Diana" and "Olivia." Post created by Tumblr user poweredbynew.

[5.3] In a similar post garnering more than 8,000 notes, Tumblr user jameswesleys (2015) remixes another music video of Kiyoko's—this time using the video for her song "Girls Like Girls"—and scores it with 1D's 2012 hit "I Would." The lesbionic potential of 1D's "I Would," a song that pledges the singer's everlasting love to an unavailable girl, is maximized through its pairing with Kiyoko's video, which tells the story of a teenage girl whose same-gender love interest has a boyfriend. This video remix gives concrete form to the mental gender-swapping that many lesbian fans engage in when singing along to 1D's supposedly heterosexual songs. The use of Kiyoko's visuals alongside 1D's songs and lyrics not only literalizes the lesbian potential of the boy band's work, but also explicitly carves out space within lesbian 1D fandom for queer women of color.

[5.4] Kiyoko, a multiracial Japanese-American lesbian, has spoken frankly about her sexuality since publicly coming out in 2015; dubbed "lesbian Jesus" by her fans, Kiyoko dedicated her 2018 Video Music Award for Push Artist of the Year to queer women of color (Nicolaou 2018). Kiyoko has directed all her own music videos since 2015's "Girls Like Girls," and stars in a majority of them as well. Many of these videos feature Kiyoko successfully romancing a woman, often another woman of color (see the music videos for "Sleepover," "Feelings," and "What I Need"). The music videos utilized in the aforementioned Tumblr posts, "Girls Like Girls" and "Cliff's Edge," subvert representational tropes common to depictions of lesbianism in music videos; the romantic exchanges they portray are neither hypersexualized nor stylized for the male gaze, and the women in them are depicted as desired and desiring sexual subjects. Posts like these redirect fans' attention from the boys themselves to the lesbian fantasies that the boy band enables.

[5.5] Another wildly popular genre of lesbian 1D content on Tumblr is Larry Stylinson "femslash": art and fan fiction that reimagines Styles and Tomlinson as two girls in love. Tumblr user twotalkaholics' "fem!larry" illustration (2014) features Styles and Tomlinson engaged in a passionate liplock, with Styles' iconic mane of hair cascading down her back and Tomlinson wearing a short black skirt (figure 3). Posts like this are common on Tumblr both within and beyond 1D fandom; here the illustration highlights the band members' lesbian aesthetic appeal (marked by their androgynous appearance and boyish sartorial preferences) and disrupts the notion that it is exclusively straight girls who are invested in "shipping" Larry Stylinson. Instead of simply asserting that the Larry Stylinson phenomenon reveals the truth of Styles and Tomlinson's secret romantic relationship, fan works like twotalkaholics' fem!larry illustration frame "Larry" as a multipurpose fantasy, one that is flexible enough to accommodate a diverse fan base's wildly differing emotional needs and sexual desires. While much of the content produced by lesbian Directioners on Tumblr highlights the band's appeal for lesbians, femslash like this goes one step farther by imagining the boys as lesbians, literalizing the lesbian erotic potential found in so much of 1D's work.

Figure 3. Fan art created by Tumblr user twotalkaholics, depicting Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson as two girls kissing.

[5.6] The lesbian 1D fandom that coalesced on Tumblr helped to create, connect, and support an entire ecosystem of queer women writers and artists, from visual artists creating fan art, to fan fic writers, to alt-pop stars like Kiyoko. This network of lesbians and other queer women once again calls up the legacy of the Women's Music Movement. The women who were involved in this movement—as artists, listeners, and workers—were brought together under vastly different circumstances from those of lesbian Directioners; women's music was by, for, and about women, and the record labels created as part of this movement attempted to train and employ as many women as possible. However at odds with this legacy boy band fandom may seem, lesbian Directioners' use of Tumblr to form a creative subculture similarly fostered community support, the circulation of lesbians' creative work, and a critique of heteronormativity in the popular music industry.

[5.7] This millennial remixing of lesbian feminist political goals denaturalizes the supposed heterosexuality of boy band fandom. Lesbian fans' ability to rework texts that are marketed as heterosexual and build community through these reappropriations casts doubt on the popular conception of boy bands as an exclusively heterosexual cultural phenomenon. Indeed, boy band fandom also gives heterosexually identified girls the opportunity to explore their sexuality and gender presentation.

[5.8] The widespread and prolific nature of lesbian 1D fandom on Tumblr influenced fans throughout the platform; because of Tumblr's open structure, all 1D fans were exposed to lesbian readings of the band. The platform's ability to circulate lesbian subcultural interpretations of the boy band so widely allowed lesbian fans to reshape 1D fandom on Tumblr writ large. This contact between lesbian- and nonlesbian-identified 1D fans again highlights the strategic similarities between women's music and lesbian 1D fandom on Tumblr. Within the context of the Women's Music Movement, many lesbian feminists saw women's music and the community surrounding it as a potential site for the political, sexual, and social transformation of nonlesbian-identified women. Ultimately, these lesbian rereadings of boy bands' performances exposed all 1D fans to queer readings of the boy band while also pushing back against the notion that only queer or lesbian-identified performers are appropriate subjects of lesbian fandom, desire, and creative energy.

6. Fandom and performance in every direction

[6.1] By embodying the queer joy of lesbian 1D fandom, Every Direction's performances extended the radical sense of possibility generated by the link between boy bands and Tumblr's queer feminist subcultures. My interviews with the group's members revealed these performances to be the product of a significant amount of fan labor, much of which was performed within digital fan communities. Though Shannon, who performed as the group's Niall Horan, says that her love for the boy band at first felt like a joke, interacting with other fans sparked a deeper interest in the band's queer potential. In our interview, she noted that having access to a community of fans who were dedicated to making the boy band's queer subtext visible inspired her to think more deeply about 1D's relevance to her own gender and sexual identity. When asked why Every Direction chose Tumblr as their primary social media platform, Shannon cited Tumblr's status as a major hub for 1D fandom, saying that she considered the platform to be 1D fandom's primary home.

[6.2] The group's recognition of Tumblr's dominance among fellow Directioners also meant that the bois turned to the platform to learn about the band, their characters, and fellow fans, highlighting Tumblr's status as the home of both 1D fandom and queer and lesbian fandoms more broadly. Tumblr posts such as jack-nought's simple declaration that 1D is lesbian culture and twotalkaholics' fem!larry illustration comprise one crucial way in which the boy band's queer potential becomes visible. When asked about the beginning of her interest in 1D, Shannon said, "as we got into it, you know, it's like we were listening to everything differently, suddenly like all of their songs had all of this amazing queer subtext, and then you get into the whole fandom aspect of it, and all of the Larry shipping, and then you realize that there's actually so much queer content to work with. And I think that definitely through Every Direction I became a much bigger fan of One Direction" (Shannon M., personal communication, October 11, 2016). Not only does Tumblr help to actively cultivate such lesbian rereading practices, it also facilitates conversations among queer fans who are both consuming 1D's music and producing a variety of queer fan texts.

[6.3] For Cheryna, who performed as Every Direction's Zayn Malik, Tumblr served as an authoritative source of current, in-depth information about 1D. It is difficult to make sense of a performance group like Every Direction outside of the context of queer women's prolific engagement in 1D fan communities. Though the group's members were quick to emphasize their roots in the Bay Area's queer community, Every Direction was equally indebted to a lineage of fans, both queer and not, who used social media platforms like Tumblr to create and share their own interpretations of 1D's songs, videos, and group dynamics. Cheryna specifically named Tumblr as a crucial component of the character research that she undertook in preparation to perform as Malik, saying, "I would search the web or like Tumblr, just Tumble. I would just go on Tumblr and I would check out all of the things going on" (Cheryna G., personal communication, October 11, 2016). This use of the platform is evident in the group's Tumblr page, which features gifs of the 1D boys affectionately roughhousing alongside meticulous drag re-creations of official band photo shoots (figure 4) and promotional flyers for Every Direction's lone music video. Every Direction's queer reimaginings of the boy band's manufactured pop persona were enabled by Tumblr's exhaustive record of each 1D interview, music video, and photo shoot, the existence of which is a testament to fans' dedication to their role as the band's unofficial documentarians.

Figure 4. Re-creation of a One Direction photo shoot featuring the members of Every Direction. This photograph was posted to Every Direction's Tumblr page alongside the original One Direction photograph, along with the caption "OH yes this is gonna start happening. Prepare yourself!"

[6.4] Every Direction's performances also highlight the contemporary boy band's roots in Black male R&B groups of the 1980s and 1990s. Every Direction's preference for matching clothes and choreographed dance routines deviated from the mismatched clothing and refusal to dance that were hallmarks of 1D's unique spin on the boy band phenomenon. The drag king group's adoption of these practices was a throwback to boy bands of the late 1990s, which were largely based upon Black male vocal groups like New Edition, Blackstreet, and Boyz II Men. These earlier boy bands, which were influenced by the emerging musical genre known as new jack swing (Harrison 2011, 17–19), all consisted of four to five members, used vocal harmonies, and frequently traded in romantic ballads. Additionally, each of these groups—and many of their contemporaries—wore matching or coordinated outfits, and performed tightly choreographed dance routines in their music videos and/or live shows. The white boy bands of the late 1990s, such as the Backstreet Boys and NSync, relied on the formula for success that was developed by these Black male vocal groups. The dance routines and matching outfits favored by Every Direction thus call back to these previous boy bands, which are all too often erased in discussions of the boy band phenomenon. While 1D attempted a rockist appeal to "authenticity" via their slightly scruffier appearance and lack of choreography, Every Direction's performances simultaneously drew attention to the racial history and queer appeal of the contemporary boy band. The performance group's multiracial tribute to 1D also gestured to the racial diversity within 1D fandom, which was seldom acknowledged in media coverage of the boy band's fan base.

[6.5] Every Direction's creative reworking of 1D both draws from and contributes to lesbian 1D fandom's expansive reimagining of what the boy band can be. Just as fem!larry unearths new, subtextual facets of the boy band's appeal in its literalization of 1D's lesbian potential, Every Direction's group members and performances give form to a queer, multiracial vision of the boy band. In my interview with Rachel, the group's Harry Styles, she described her preparations as a Black woman who was performing as one of the world's most famous white boys, saying, "I definitely watched music videos, I read a lot of articles, you know, followed on Twitter, watched the 1D movie a lot of times, and just tried to study things about his personality because obviously like, I'm black, I don't look like Harry. I can't get Harry's hair or anything like that, and so it was like, how can I exude his personality while performing so that people know who my character is?" (Rachel W., personal communication, October 11, 2016).

[6.6] Rachel's description of the labor that she did in preparing to perform as Harry Styles points to the wide range of lesbian aesthetics embodied by 1D. Rachel notes that Styles's look in particular is reliant on a "specific kind of rocker style" that she did not try to emulate, but she remained determined to "become him as a person" through physical mannerisms, intonation, and personality. In our discussion, Rachel emphasized the amount of work that her transformation into Styles represented, saying, "that took a lot of research in to how he talks, what he does, all of the jokes that he plays." Though Rachel does not identify with the white alt-rock masculinity that Styles embodied during the group's third and fourth album cycles, the research that she described doing allowed her to recognize their commonalities in speech, mannerisms, and demeanor as well as helped her to pinpoint the band's different aesthetic eras. Through her performance of fan labor—the act of rifling through the unwieldy number of articles, videos, and photographs that attempt to capture the essence of a performer—Rachel took on Styles's role within the group.

[6.7] For Every Direction's members, digital 1D fandom was closely related to the joy that the group took in reinterpreting the boy band's work. Rather than existing as a counterpoint to mainstream 1D fandom, Every Direction's performances drew energy from the boy band's massive global following. Rachel described being a member of Every Direction and engaging with digital 1D fandom as two key components of her own experience as a fan, saying, "to me the joy of 1D was just hanging out with my friends, trying to conjure up the essence of this boy band, and then also exploring some of the fandom." In addition to watching fan-made 1D music videos and keeping up on band-related gossip, Rachel described using online fan communities to find another 1D themed "boi band" in Minnesota.

[6.8] The group's connection to 1D fan communities was coupled with a rootedness in the Bay Area's lesbian and queer communities: Every Direction's Tumblr page advertises performances at the White Horse Inn, Oakland's oldest gay bar, and El Rio, a San Francisco gay bar and community space that was established in 1978. Every Direction also hosted and performed at a benefit show for Lyon-Martin Health Services, a community-based health clinic offering trans-inclusive health care to women. Initially founded in 1979 as a clinic for lesbians who had difficulty accessing adequate health care, Lyon-Martin now serves women of all sexualities and trans people of all genders. Every Direction's benefit night, which included 1D trivia, live performances, and a DJ, linked Lyon-Martin's queer and lesbian feminist mission with the 1D fan communities from which the group pulled inspiration. The group's connection to a queer politics that is both trans-inclusive and tied to lesbian feminist history speaks to the ways in which many lesbian Directioners negotiate and make sense of lesbian political histories.

7. Conclusion

[7.1] Though Every Direction (and their slightly more well-known boy band counterpart) ultimately broke up, the group lives on in its digital archive. Through their collective performances and individual statements, Every Direction's members continually reaffirmed the radical sense of possibility generated by this link between boy bands and Tumblr's queer feminist subcultures, whether it was through the lesbian boi band aesthetic that the group made visible or the queer joy that their performances engendered. In this sense, the group's work embodies one vision of the queer futurity that José Muñoz has described as "a backward glance that enacts a future vision" (2009, 4). Their insistence upon exposing the boy band as a site of affective investment and queer political energy challenges the pervasive relegation of lesbian art and performance to the realm of subcultural production, a phenomenon that imposes lesbian feminist political priorities on contemporary expressions of lesbian identity. The fantasy life that Every Direction's performances conjured—one in which the Bay Area's most famous boi band reigns supreme, and everyone in the club finds their dream girl by the end of the song—invoked a queer utopia that is too seldom seen, even if it only lives on in the hearts of the group's digital fangirls.

[7.2] Although Tumblr fandom of 1D may be in decline following the boy band's hiatus, the platform remains vital to queer and lesbian fan communities. The digital fan base that coalesced around Every Direction may not be seeing a new Tumblr post by the group anytime soon, but there are countless new pop cultural phenomena that will continue to capture their attention and inspire them to create something of their own. Likewise, 1D's queer and lesbian fans still use Tumblr to critique and celebrate everything the boy band was, is, and could have been; their use of the platform to reinvent the object of their fandom continues to shape queer fan practices on Tumblr.