1. Introduction

[1.1] While recent public discourse has warned about the rise of social bots in politics, their presence has applicability for those studying the construction and maintenance of fan communities online. Social bots, in entertainment as in politics, are used to influence the impressions, experiences, and behaviors of fandom on the internet today. Responsive to this environment, fan scholars must interrogate the presence of these bot networks for their impact on online fan cultural activity. This automated enhancement of a celebrity's digital presence matters for its role in creating, fostering, and reifying the social inequities between users and celebrities on social media platforms.

[1.2] A social bot is a "computer algorithm that automatically produces content and interacts with humans on social media, trying to emulate and possibly alter their behavior" (Ferrara et al. 2016, 96). Of these automated processes, social bots try to pass a version of the Turing test, in which a machine attempts to exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from humans (Turing 1950). Social bots attempt to participate, structure, and shape public discourse. As Gregory Asmolov (2019) discusses it, bots as social actors "increase the visibility of information." The use of these social bots by celebrity and entertainment brands is thus a practice precisely about expanding their digital presence. One way they influence the organization of user attention online is by contributing more engagement—more likes, more comments, and more retweets—to existing social media posts that works to increase the reach of social media content to interested users.

[1.3] Their capability, however, is not merely through the amplification of media visibility. It also includes the production of cultural discourse that manages audience perception. Take, for example, the controversy over accusations that Lady Gaga or her fans attempted to sabotage Venom (2018) during its timed release against A Star Is Born (2018) (Krishna 2018). The alleged strategy found user profiles posing as Twitter moms to amplify bad word of mouth against the competing film. One user, @Yves_new, appeared to mimic the same divisive rhetoric used by Russian political bots, stating, "Just got back from seeing #Venom in theatre .. So disappointed. Lots of democrat nonsense, pushing LGBT agenda down throat too. Disgusted. I can't believe I am saying this but I might have to take the kids to see #AStarIsBorn tomorrow to make up for the terrible night. Very sad" (Gemmill 2018). This example reflects a strategy of what is known as astroturfing—masking a message's sponsors to create the impression of grassroots support. Such examples of astroturfing represent part of the unique dangers for democratic discourse online in the relationship between music celebrities and their audiences, especially as these incidents mirror how social bots can amplify and alter user perceptions across digital platforms.

[1.4] Studies of digital fandom must be attentive to the growing presence of social bots designed to automate and regulate the visibility and perception of economically and politically privileged actors (Metaxas and Mustafaraj 2012) and entertainment brands (Echeverría and Zhou 2017). As social media platforms become the terrain where the control of perception is fought, it is imperative that humanities scholars work to archive and critique the impact of these automated behaviors on the affective processes of online fandom today.

2. Tribal pop fans and social bots

[2.1] Since the arrival of the Beatles in the United States in 1964, images of fans have been a visible spectacle in the media presence of musicians (Ehrenreich, Hess, and Jacobs 1992). Images, most often of screaming teen girls, have been the aesthetic framing through which stars pierce the zeitgeist. In the digital age, the use of fans as a marketing frame has continued, with some key transformations. This new circumstance reflects how fan communities have become increasingly more public online over the past three decades of the internet. As Nancy K. Baym (2018) suggests, the rise of networked computing and the internet created opportunities for organizing music fandom into digital communities. In its early days, such participatory forms of fandom were organized around the margins of the internet, accessible through decentralized text-based forums like group-sharing note files and bulletin boards that were often city specific. With the rise of the hyperlinked World Wide Web, fandom was accessed through online service providers and other amateur-run HTML websites. Today, outlets for fandom have become concentrated through social media platforms like Twitter, Tumblr, and Instagram. Fandom is arguably more public; no longer is it as shaped by fan-created content on local platforms. The net effect has been a growing commercialization of these communities.

[2.2] Indeed, fandom is now the logic of global media marketing itself. This emphasis on communities of fans can be observed in the transition of popular music's stars onto social media platforms like Twitter. In the early 2010s, entertainment journalism frequently gawked at pop stars like Lady Gaga referring to their fans as communities of followers. As the labeling of other fan groups like the "Katy Cats," "Beliebers," "Swifties," and "Directioners" continued into the early part of the decade, the Atlantic's Jason Richards (2012) questioned the tribal state of pop music. These tribes comprised the sphere of internet culture known as "stan culture," a portmanteau of "stalker" and "fan" derived from Eminem's song "Stan" (2000), which narrated the one-sided affections of a fan invested in Eminem's stardom (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stan). Lady Gaga's "Little Monsters" appeared among these groups and were repeatedly referenced in the singer's talk show appearances. This group identity did not merely foreground the performer's organization of her fans into a networked community online; it also facilitated vital forms of community. For in Gaga, they saw an artist whose music video productions and avant-garde fashions mirrored the growing acceptability of explicitly queer and LGBTQ+ themes in popular culture. Some of these fans invested in the performer as their "Mother Monster" because her celebrity made them feel uniquely visible as gay and queer subjects. This type of celebrity-fan relationship is not new. Judy Garland, Annie Lennox, and Dolly Parton, among others, are all artists whose celebrity has offered narratives and feelings of queer visibility in the public sphere. With the arrival of Gaga's social media network, Little Monsters (http://littlemonsters.com/), this feeling of queer visibility became digitally networked into fan and audience communities that originally served as a resource for Gaga's celebrity presence online.

[2.3] Monickers like the "Little Monsters," however, were not just an expression of celebrity-fan intimacy. During this same period, ancillary celebrity journalism and marketing content producers like PopCrush began to engage these groups through their use of reader polls, specifically in the development of the "Best Fan Base—Readers Poll," which sought to generate traffic from these networks of celebrity fans (https://popcrush.com/best-fan-base-readers-poll). Within these fan communities, users were compelled to recruit their fellow fans to go vote in earning the crown of best fan base—a media strategy that indicates how entertainment marketing borrows its metaphors from the political process. These fan bases were part of a discourse that reflected the economic and marketing value of these networked platforms, as algorithms and hashtags worked arduously to extend and manage the visibility of entertainment brands and personalities online. The success of pop stars on social media reflected their attempts to streamline and augment their audience reach by increasing the feeling of intimacy with their fans through their social media presences. These calculations have succeeded in creating the necessary forms of affective investment for users to produce marketing content, and therefore value, for these entertainment brands and personalities (Andrejevic 2008). Moreover, this social media sharing and producing of content also helps fans receive attention for their own digital presence while promoting the visibility of their favorite stars to other interested users.

[2.4] While the circumstances of bots on platforms are contemporaneous with concerns about political legitimacy, there are reasons to be suspicious of their influence on social media fandoms. The latent democratic impulses that marked the initial rise of internet technologies have started to crater. The growth of fake followers and inflated metrics on social media now work as drivers of celebrity marketing, reflecting how legacy media industries have been shaped by the emerging logic of social media networks in both their casting and marketing decisions. In 2015, Music Business Worldwide reported its audit of follower counts of popular music stars. Katy Perry, Justin Bieber, Taylor Swift, Lady Gaga, and Rihanna were found to be the biggest offenders; their fake followers comprised between 55 percent and 65 percent of their total follower count (Music Business Worldwide 2015). After 2016's election-year controversies on its platform, Twitter has started to take the issue of fake followers more seriously. In 2018, the New York Times reported the company's efforts to delete millions of suspected bot accounts (Confessore and Dance 2018). These numbers reflect the ongoing tensions in the democratic and authoritarian underpinnings of contemporary social media culture that extends beyond the field of politics into entertainment.

3. Automating fan marketing

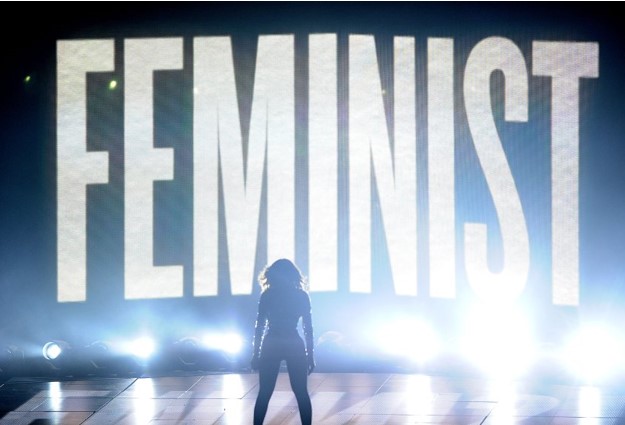

[3.1] Identity sometimes functions as a narrative we tell ourselves about our bodies and others as part of a shared community based on the intimate truths of social life. To this point, a certain logic in contemporary celebrity and entertainment culture works in dialogue with the celebration of various social identities. Over the past decade, issues of identity and its politics have taken a renewed place in the marketing of key music personalities. In 2011, Lady Gaga released her album Born This Way (2011), which underscored the performer's relationship to LGBT acceptance through her foundation's focus on antibullying efforts (Ferraro 2012). When Beyoncé accepted MTV's music video vanguard award in 2014, it featured the singer standing in front of the tall letters spelling "FEMINIST" (Bennett 2014) (figure 1). As Taylor Swift moved into her promotional campaign for 1989 (2014), her evolution on the politics of feminism was made a centerpiece of her cultural appeal (Swift 2014). The construction of politicized social identities poses many upsides for entertainment brands beyond just the display of socially conscientious art. Fan investments in these stars are intensified by the centering of aspects of identity in their works. In keeping with traditional analyses of music celebrity (Marshall 1997), these cultural efforts foster a more authentic connection between celebrity and fan. That these artistic expressions appeal to various meanings of cultural identity is of interest here precisely because it underscores how aspects of identity politics, critiqued by some as a form of tribalism, appeal to the networking processes of social media. In centering cultural identities in their work, these celebrity artists have been able to speak more intimately to the ways that identity connects to the heart of how we imagine ourselves. As entertainment branding has shifted to a focus on social media networking, it has recentered how female pop stars in particular function as avatars for various cultural groups, which in turn has fostered greater forms of intimacy with their fans.

Figure 1. Beyoncé standing in front of letters spelling out FEMINIST, MTV music video vanguard award, 2014.

[3.2] In her commentary on gift culture, Abigail De Kosnik (2009) takes up this specific component of fandom in her analysis of Janice Radway's Reading the Romance (1982) to argue that romance novel culture represents a space in which fans receive the gift of intimacy with themselves through the private practice of reading. Relatedly, fans seek the production and consumption of fan content online as one way they can articulate their identity through their imaginative engagements with their idols. Yet it is necessary here to interrogate the ways that entertainment branding now standardizes and automates this fan cultural activity. With these bot-led amplification processes, fan labor is stimulated and spread across more users through social media engagement. In this regime, fans work in tandem with social bots as unpaid or low-cost marketers who secure the visibility of these stars and brands online.

[3.3] Social bots help explain the arms race of the early 2010s, in which Lady Gaga and Justin Bieber vied for social media dominance on Twitter (Snead 2012). The use of social bots to increase follower counts has yet to justify legal or political concern because these bots can be perceived as less threatening as they affect primarily already interested users. This perception minimizes the ways that such commercial speech represents distinct threats to the health of public discourse online. In fall 2013, pop stars and their fan communities were publicly feuding across social media thanks to multiple high-profile album releases. Gaga's Little Monsters, threatened at the idea that their star might not achieve the same commercial success as previous albums, grew ugly in fan forums and on social media as they bullied competitors like Katy Perry and her fans. Emmanuel Hapsis (2013) positioned this bullying within traditions of misogyny in popular culture. The behavior of fans warring with others on social media grew to the point where Lady Gaga herself issued a tweet stating: "Don't fight with Katy's fans, or anyone. STOP THE DRAMA. START THE MUSIC. Pop music is fun, and these 'wars' are not what I'm about" (Robinson 2013).

[3.4] This intensity of investment was not an aberrant quality in Gaga's fandom, particularly as her work highlights issues of LGBT identity and politics with previous albums like Born This Way (2011). That her fandom has had a legacy of problematic activity online points to what might be described as a conservative impulse—conservative precisely as these fans attempt to work their bodies in ways that conserve their belief in her stardom. This textual and toxic labor, while not universal among fans, reflects the ways that Gaga's social media branding worked to mobilize real bodies in the world. It reflected fans' needs to preserve the status quo of her celebrity at a time when her career had taken on resonances for their own personal identity in the public sphere. This perception of her celebrity was inflated, built partially out of the mobilization of these bots to provide a digital infrastructure for her stardom. These bots likely amplified, and thus helped control, the specific types of meanings that circulated around her entertainment brand and stardom. If fans felt deeply invested in the range of meanings coalescing around her celebrity, it is attached, at least in some part, to this automation of user attention and its relationship to producing fan activity. This bot amplification of a celebrity presence online illustrates the antidemocratic undertones of an industry that uses the language of politics to market its appeal through social media networks.

[3.5] Fan scholars must reckon with digital social bots not just through metaphors like advertising but also through their ability to organize the affective bonds between celebrity and fan. Take the case of the "Beyhive," who were once known for their hostile approach to fandom through the spray of Bee emojis on critical commentators of Beyoncé. That routine behavior of the fan group appears to have arisen after the artist's recent political turn in her work. Beyoncé (2013) and Lemonade (2016), in particular, have centered her celebrity as a type of avatar for Black feminism following critiques from prominent Black musicians (Belafonte 2012) and intellectuals (hooks 2014). Beyoncé's status as a political avatar is not incidental to these fan attacks. The Beyhive targeted musician Kid Rock's Instagram account with nearly 40,000 comments following his racist remark that he preferred slender white women compared to Beyoncé (Lindner 2015). Jezebel's Clover Hope (2016) discovered in her querying of these social media posters from other Beyhive incidents that while many of these comments may appear to be genuine, the bee or lemon emojis represent a mix of fan and bot posts. Such intermixing of fan and bot media posts suggests the ways bots may reinforce the crowd and mob psychology of fandom. Clearly there is a need to further distinguish the extent of this automated activity, but this circumstance raises clear questions about the design and function of robotic actors in shaping the affective processes of digital fandom today.

[3.6] While social bots may pose less risk for entertainment marketing than political attacks on the United States, the automation of Twitter discourse and the attempted automation of fans should be viewed as antidemocratic developments on these platforms. The presence of toxic behaviors by fan communities online can be linked partially to these conditions. As scholars, we must question the ways these social bots help corrode public discourse online and the extent of their influence on digital fandoms today.