1. Introduction

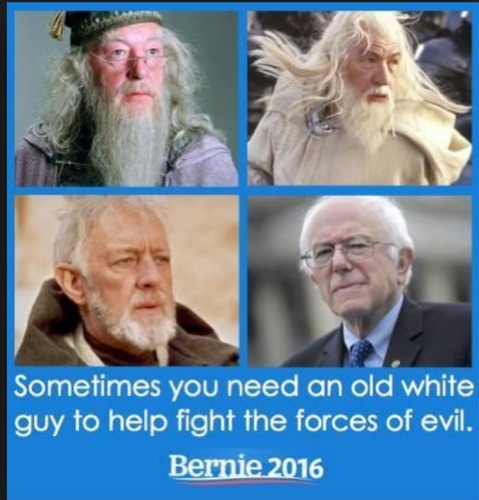

[1.1] Against a bright blue background, a meme proudly declares, "Sometimes you just need an old white guy to help fight the force of evil" above the words "Bernie 2016." In the image, Bernie looks out seriously alongside Obi-Wan Kenobi, Dumbledore, and Gandalf (figure 1). These choices were particularly salient; Bernie Sanders frequently appears as each of these characters in other memes, but the meme maker undoubtedly had other options. They could have gone to the pages of Marvel for Professor X, into the Disney vault for Merlin, or to the Back to the Future franchise for Doc Brown. The well available for heroic older white men is deep. For older white women, there are far fewer heroines to choose from. Indeed, the most frequently deployed older woman in political memes and discourse around the 2016 US presidential election, General Leia from the Star Wars franchise, is depicted as her younger self. Images of older white women in media are certainly available, and Clinton is frequently depicted through these unflattering lenses of Disney witches and dour scolds. This shouldn't surprise any film fan. Studies have demonstrated that not only are older women underrepresented in popular film but they also are depicted as less good (Bazzini et al. 1997). Heroic older women may be plentiful in life, but they are few and far between on screen.

Figure 1. Bernie Sanders associated with heroes Dumbledore, Gandalf, and Obi-Wan Kenobi.

[1.2] The availability of such images has become a matter of US national importance as fan-created memes and popular culture references have become an increasingly important part of political discourse. Indeed, candidates themselves use these touchstones. Hillary Clinton compares the vitriol directed at her by supporters of Donald Trump to the taunting of Cersei Lannister from Game of Thrones in her 2017 book What Happened (McCluskey 2017), while Trump tells a young boy at the Iowa state fair that he is Batman (Cavna 2015). Traditional media has also been quick to draw comparisons between politicians and popular culture figures. In a February 2019 episode of his TV show, Seth Meyers jokes that Donald Trump learned he could go back to the future by watching a documentary with Bernie Sanders (the 1985 film Back to the Future), playing on memes comparing Sanders to Doc Brown. Jimmy Kimmel draws on Captain America: Civil War (2016) in a fake trailer depicting Sanders as Captain America, Trump as Iron Man (described as a "diabolical Billionaire"), and Clinton as a (cackling) Scarlett Witch.

[1.3] Although popular culture references are woven into traditional media and the discourses of candidates, they are nowhere more prevalent than in internet memes. Because memes are often single images, they frequently rely on the shorthand of existing popular culture texts, such as films or television series. Chmielewski (2016) refers to memes as "the lingua franca of the modern campaign," while Ryan Milner describes memetic media as "a lingua franca…for mass participation" (2018, 5). However, if memes function as a language, then it is important to consider the available building blocks of their vocabulary.

[1.4] Despite ample consideration of the role of social media, memes, and even fandom in recent elections, we have yet to consider the way that these discourses are limited by the available language of popular culture and the problems of gender representation in popular media that are replicated in its use in political discourse. Popular-culture-centered memes about the 2016 US presidential candidates were shaped by the ample availability of highly salient popular culture references for depictions of men and by the limited referents, particularly positive referents, available for women. Here I trace the types of memes depicting Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton in order to better understand how the limited depictions of women in legacy popular culture have affected fan-made and viral memetic texts. Details of these texts, like the existing dynamic between iconic characters in these popular culture texts and the disciplining of ambitious women through the tropes of the villainous woman or the masculinized woman, place female candidates at a disadvantage in the meme wars. Although memes are understood along linguistic lines by discussing their vernacular (Milner 2018) and genre (Wiggins and Bowers 2014), this is not sufficient to elucidate how memes function as a single articulation. Memes draw on fan cultures and popular film and television, so it is vital to understand the limitations of this lexicon—that is, the components that comprise the language used to form the articulation we see when we look at a meme.

2. Literature review

[2.1] The literature shows that pop culture memes play a crucial role in political discourse, but what is rarely considered, in part because these studies focus primarily on memes made by fans of male politicians, is the extent to which pop culture is skewed to favor male heroes. Given the significance of popular culture to political memes, greater attention must be paid to the specific popular culture subject used and its limitations. Limor Shifman emphasizes the importance of media culture, noting that there is a "heavy reliance on pop culture images in political memes" (2014, 138) that adds layers of meaning associated with the text to comment on politicians like Barack Obama and events like Occupy Wall Street. Shifman argues that the use of popular culture in these instances is largely open to viewer interpretation; in Star Wars-based memes depicting Obama as Luke Skywalker, for example, "the Force is with Internet users" may be either "glorifying Obama" or criticizing Obama's "construction as a superhero" (150). Following Shifman (2014), I argue that that the "keying" of a meme's tone and style (Shifman 2014, 39) as well as its political valance powerfully delimits the preferred reading of many memes and the references used within them.

[2.2] The selection of memes in political discourse is not just a function of the available memes but also the work of fan culture in relation to those memes. Milner argues that "pop media is essential to memetic participation" (2018, 67), explaining that memetic grammar depends on reappropriation and is in part about "borrowing from the contributions of others and transforming those contributions into something unique" (61). In this way, we can see memes, especially but not exclusively memes based on popular culture, as related to other forms of transformative works that have long been part of fan cultures. Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green (2013) critique the model of the meme as frequently distorting the role of human agency in spreading media content, flagging fandom instead as a reference point that has innovated in participatory media. Milner's (2018) and Shifman's (2014) focused studies of memes demonstrate the existence of a specific and complex relationship between memes and the communities that spread and frame them, pushing beyond the previous models of memes as self-replicating that Jenkins, Ford, and Green rightly critiqued. Further, although neither text talks much about fans, these scholars' interest in affinity groups, the use of popular culture, and reappropriation call for a consideration of the role of fan logic in meme culture. The labor performed by political fans, including the circulation and production of memes, can be an important component of the creation and maintenance of a citizen's political identity, as well as a way to attempt to persuade others, celebrate victory, and even antagonize others (Penney 2017). While making these appeals, political fans frequently draw on other cultural touchstones, including popular media (Kohlemainen 2017; Penney 2017), thereby performing multifaceted labor to engage with the meanings and iconography of both the political figures and the popular media texts they put into conversation. Pekka Kohlemainen (2017) compares this reframing of politicians through new narrative conventions and character types to crossover fan fiction. While limited, the social media capital that is essential to campaigns can be supported by political fan behavior (Kohlemainen 2017; Penney 2017) and can involve the creation of both transformative and affirmational narratives around candidates. Transformational memes or narratives may substantively reimagine or reframe the political candidate, the media text supporting them, or both. Affirmational memes or narratives may support the candidate's campaign message, or more frequently simply an impression of them as a good or bad person, while simultaneously either affirming or transforming the source media text that the candidate is crossed over with. This is crucial because it requires an assessment of how the meme engages the canon of both the political and media texts.

[2.3] The memes created for the 2016 presidential election demonstrate how two different forms of fandoms, political fandoms and media fandoms, are active in political memes. Although we cannot assume that every one of the numerous political memes based on Star Wars was created by fans of either the franchise or the candidates, we can see how they can be understood as contiguous with fan practices, and they may be unpacked using strategies from fan studies. Furthermore, the extent to which it is being either created or perceived through the lens of a primarily political fandom (Penney 2017) or a primarily media fandom will affect the way we can understand a meme's operation from a fan studies perspective. For example, a meme made famous after Jessica Chastain shared it on Instagram of Hillary Clinton as Danaerys Targaryen from the Game of Thrones TV show (2011–19) standing proudly with a dragon on her shoulder can be understood as functioning differently from two fan perspectives (figure 2). From the perspective of Game of Thrones, this is unquestionably an example of transformational fandom, but for Clinton fans, this could be considered an example of affirmational fandom, which borrows the positive valance of the character from this popular series to emphasize attributes that they wish to celebrate about their candidate—in this case, strength and nobility.

Figure 2. Meme of Hillary Clinton as Danaerys Targaryen, dragon on her shoulder, from Game of Thrones (2011–19).

[2.4] Crucially, which fandoms and media circulate online with enough salience to make memes effective is essential to what kind of appeals can be made. Milner notes that "memetic reappropriation is constrained by the cultural systems that simultaneously facilitate it" (2018, 85). While this crucial relationship between popular culture and memes has been acknowledged in research on memes (Shifman 2014; Wiggins 2017), the extent to which this necessitates a consideration of the representations and structures of traditional media as a constituent element of new media discourses has not been considered. Film and television culture may be understood as a central resource for memes, but new media scholars analyzing memes rarely consider this culture itself, its features, and its limitations.

[2.5] Understanding political memes from the 2016 US presidential election can benefit from an understanding of gender representation and tropes in traditional media and gender representation and stereotypes in political media, as well as an understanding of the relationship between memes and politics themselves. Ample research has established that women are underrepresented both as speaking and lead characters in traditional media, particularly in the action and adventure films often referenced in memes (Smith et al. 2018). Further, depictions of female characters frequently fall into traditional gendered tropes (England, Descartes, and Collier Meek 2011). Smith et al. found that only 23.2 percent of characters in action-adventure films from 2007 to 2017 are female (2018, 6). Older women, like those who typically run for political office, are particularly rare. Of the one hundred top films in 2017, only five have a lead or colead aged forty-five or older (Smith et al. 2018, 6). Further, older women and those who do not conform to a feminine ideal are often framed in negative, even villainous, ways in film and television (Bazzini et al. 1997; Li-Vollmer and LaPointe 2009; Robinson et al. 2007).

[2.6] This can be further complicated by a kind of representational double bind, where feminist imperatives of being seen and heard can involve the transgression of feminine norms (Rowe 1995)—a transgressive script that comes with its own limitations that can pen women into masculinist norms of strength and violence (Brown 2004; Coulthard 2007) or can frame them as abject (Rowe 1995). These images of strong women often need to be paired with clear markers of traditional femininity in order to make them palatable for audiences (Baker and Raney 2007). This also echoes the double bind that many women in politics find themselves in. Shawn Parry-Giles (2014) notes that news frames are used to discipline Clinton for her entry into male-dominated social and political spaces. Such spaces often frame her as insufficiently feminine and insufficiently authentic, thereby setting up political ambition and femininity as antithetical. Yet these negative surveillance and frames repeatedly recede when Clinton steps away from pursuing leadership roles. Popular entertainment frames more frequently associate men with leadership roles (Smith et al. 2012) and align empowered women in leadership roles with youthfulness, attractiveness, and physical prowess, sometimes associated with the trope of girl power (Gonick et al. 2009). Similarly, news frames have been found to discipline women in the public sphere for failing to conform to feminine ideals (Parry-Giles 2014). Taken together, these news frames leave little space for positive models of women, particularly older women, to be seen as competent, active, trustworthy leaders. Conversely, not only are male leads and heroes much more plentiful, there is much more flexibility in what is allowable for male heroes. This is exemplified in images of postfeminist masculinity (Gwynne and Muller 2013) and in the rise of the antihero in popular media (Lotz 2014).

[2.7] This inequity in media representation parallels gender inequities in politics. Scholars have suggested that women are not disadvantaged at the ballot box, but women remain underrepresented in both state- and federal-level politics (Hayes and Lawless 2016). Kathleen Dolan (2010) finds that stereotypes about what male and female candidates are good at affects voting patterns. Ana Stevenson (2018) traces many stereotypes found in memes that address women's political participation back to women's suffrage postcards, which she argues function similarly to memes. Michelle Smirnova observes that in memes featuring Clinton and Trump, "discourses often draw on gender scripts and tropes in political critique, thereby supporting a patriarchal system that privileges men over women" (2018, 4). Smirnova argues that these memes reflect a "double bind" (13) for women, noting that many of the memes directed at attacking Donald Trump worked by feminizing him, further reinforcing hegemonic masculinity's connection to images of presidential fitness. The masculinization of Clinton is particularly relevant given that her failure to perform appropriate femininity was identified as a long-standing objection to her by evangelicals (Ward 2018) and Republican women (Aronson 2018). This framing can be tied to a long history of discourses disciplining Clinton's gender performance (Campbell 1998; Parry-Giles 2014) that extends beyond Republican communities. Bradley Wiggins (2017) observes that there is significant vitriol toward Hillary Clinton and less aggression toward Trump on the Bernie Sanders' Dank Meme Stash (https://www.facebook.com/groups/berniesandersmemes/), which Wiggins argues might have helped elucidate the dynamic of the election. He also observes, "Popular culture intertextuality functions as the dominant source material for memes" (200). This centrality of popular culture images in memes, which Shifman argues "play a key role in contemporary formulations of political participation" (2014, 171), means that we must not only look at meme culture or a meme's use of popular culture but also at the limitations of existing traditional media culture. Further, the relatively limited positive pop culture memes depicting Clinton and the ways in which she is disciplined in negative ones reflect existing prejudices in the ways female characters are depicted in popular media.

3. Methods

[3.1] Scholars have approached the identification of their meme sample in numerous ways, including immersing themselves in a single location (Wiggins 2017), using specific search terms on social media sites to identify frequently shared memes (Smirnova 2018), and analyzing dozens of meme pages using quantitative content analysis (Moody-Ramirez and Church 2019). Each of these methods allows researchers to find a relatively heterogeneous set of memes for analysis. However, because my project does not seek to generalize about 2016 presidential election memes or their effects on the election but rather to provide a close analysis of a specific type of meme, I elected to conduct a virtual ethnography (Hine 2011), culling relevant memes as they appeared on my social media news feed during the 2016 election and following them to related digital spaces (such as a Reddit page conducting a photo contest).

[3.2] I collected these memes primarily via both my personal Facebook page and politically themed Facebook groups, like the well-known Pantsuit Nation, which I belonged to during the 2016 election period. Because memes are often posted out of context, I followed them, whenever possible, to their original source (like Bernie Sanders's Dank Meme Stash or a Reddit thread) to collect related memes and get a better sense of the original context for the memes as well as the context in which I encountered them. All the memes I collected were widely distributed; to my knowledge, none was made by or unique to the sharers or the places where I encountered them. To diversify and complicate my sample, when a frequently repeated theme appeared (like the appearance of candidates as Jabba the Hutt), I conducted Google searches to identify riffs on the meme and conversations that might not have been captured by my initial sampling. Although I did not track Twitter or Instagram, if I found links to memes on these platforms during my sampling, these links were followed and relevant content collected. This multipart approach helped provide heterogeneity to my sample, permitting me to avoid the bias inherent in social media bubbles. I ultimately compiled a sample of 197 meme images relevant to my study. Primary data collection took place between March 2016 and December 2016. Additional memes were collected in the analysis and writing process in January and February 2019; these memes were located through Google searches conducted to look for additional variants of key memes and to ensure the heterogeneity of the sample. These memes were checked to ensure that they were circulating during the initial collection period.

[3.3] For this analysis, I focus specifically on a subgenre of memes that are a variant on face-swap memes—that is, memes that superimpose the face of one person in a photo onto the face of another person in the same photo. However, because the presidential candidate and characters like Darth Vader or Captain America don't appear in the same image, instead of swapping both faces, these memes instead simply superimpose a candidate's face onto the media character, relying on their recognizability. This need for recognizability made characters with iconic features or costumes particularly prevalent in my sample. In these cases, characters become a shorthand for commentary on a candidate or an electoral dynamic. For example, in figure 3, a meme that circulated shortly after the election, Obama is depicted as Jon Snow from Game of Thrones, declaring "My watch has ended," above an image of Donald Trump as the Night King, declaring "Winter is coming." Here, the idea that Donald Trump is not only villainous but an active threat to society—and indeed human life—is conveyed by the choice of adding Trump's head to the Night King's body. Those who create or share this meme are able to convey a complex set of feelings about both their perception of the morality of the new president and the threat he poses by relying on others' existing knowledge of the Night King and the role he plays in Game of Thrones.

Figure 3. Game of Thrones meme with Barack Obama as Jon Snow and Donald Trump as the Night King, summarizing the meme maker's desire for viewers to understand Trump as an active threat to society and human life.

[3.4] For my analysis, I focus primarily on groupings of memes that reference a limited number of media texts or fandoms in order to gain a better understanding of how the language of popular media is deployed in gendered ways. Bakhtin describes language as potentially "socio-ideological" ([1975] 1981, 272), with different languages belonging to different groups. Memes drawing on popular culture belong to a larger social media language and a kind of memetic discourse with its own linguistic norms; they simultaneously rely on specific lexicons of media texts and fandoms. Bakhtin argues that "language has been completely taken over, shot through with intentions and accents" (293). In the cases I address here, I consider how certain political memes function as a discourse through the appropriation of a lexicon drawn from popular media. Their meaning is structured in part by the limitations of the lexicon and in part by the accent with which its language is spoken. As a result, because these memes depend on shared understandings of both political and popular culture languages, they can be read in potentially deeply conflicted and contradictory ways, depending on the reader's understanding of the way they are accented. For example, one face-swap meme depicts Clinton and Sanders sitting at a table at CNN, where Clinton appears as Leia holding a blaster and Sanders as Gandalf smoking a pipe. A Sanders supporter may read the equation of Sanders and Gandalf as a reflection of Sanders's wisdom and heroism, while a detractor might focus on Gandalf's tendency to mislead and withhold information. Similarly, a Clinton supporter may perceive Clinton as a symbol of revolutionary female strength, while a detractor might read the blaster as a symbol of problematic militarism. Most memes have a clear negative or positive valance in their intent, however, that can be discerned by either the words accompanying an image or the context in which they circulate. As a result, memes may be interpreted through a triangulation of the political meanings evoked by any words included in the meme and the contexts in which it was circulated, the cultural meanings of the media texts involved, and visual communication cues like the facial expressions chosen.

[3.5] Additional complications emerge as a result of strands of an internet subculture that make memes for the lulz (that is, humorous effect), to top others, or as part of a challenge. Indeed, several images I encountered emerged from a single photo challenge on Reddit in which an unflattering photo was presented in order to be adapted into as many memes as possible. This challenge led to images as ideologically diverse as Roadhog from the video game Overwatch (Blizzard Entertainment, 2016), Corpus Colossus from Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), and Edna Turnblad from the film Hairspray (1988). As a result, the intention and even the original use of memes are not always discernible; instead, it is sometimes necessary to follow patterns across memes. The inconsistencies that their use and motivation reveal, exemplified by the Reddit photo challenge, frequently make it impossible to clearly connect a meme and a news event or candidate's immediate branding. Rather, more general news frames, like the understanding of Clinton as inauthentic (Parry-Giles 2014) or affective commitments to a candidate linked more to team allegiance than political philosophy (Penney 2017), seem to be activated.

[3.6] It is therefore important to understand each meme as open to multiple readings, sometimes obscured in terms of its original intent, and as fundamentally dialogic (Bakhtin [1975] 1981). It is therefore crucial that memes be considered in relationship to the "social life of discourse" (269)—that is, how they are circulated, and for whom. Divorced from this context, as well as the context of other memes, readings of memes can be misleading, as can be seen in the differing readings of the meme series "Texts from Hillary." Moody-Ramirez and Church (2019) use a coding process that leads them to identify an image of Hillary Clinton looking at her phone while wearing sunglasses as a negative meme drawing attention to her emails, whereas Stevenson (2018) recognizes this image as part of a Tumblr titled "Texts from Hillary," whose play on this image generally depicts Clinton as powerful and even cool.

[3.7] Further, because memes only become memes through circulation, modification, and imitation, it is essential that we look at how memes work in conversation with one another. The pro-Sanders "Sometimes you just need an old white guy to help fight the force of evil" meme I began with has been adapted into multiple variants. In some versions, Ron Paul or Donald Trump take Sanders's place; other versions play on its premise to critique it. One version copies the meme exactly but adds a smiling Senator Palpatine, one of Star Wars' chief villains, beneath it with the words, "Yes, exactly." Another meme, which features Senator Palpatine, Saruman (a wizard complicit with the villain in the Lord of the Rings franchise), and Sanders, changes the text to read, "Sometimes you need an old white guy, pretending to be a good guy, to make things worse." This same basic memetic form is therefore used to elevate Sanders as a hero, to elevate his competitors, to question the centrality of old white men and our trust in them, and to depict Sanders as a wolf in sheep's clothing. Following this trope across multiple memes and considering the characters who are added or subtracted to influence their meaning can help us understand the conversation that is taking place through these memes. Crucially, this exercise also shows how the available lexicon of well-known media characters shapes the way this conversation can occur.

4. An uneven media lexicon

[4.1] The flexibility of the "old white guy" meme only reinforces the plenitude of white men to choose from on screen and in politics. Yet it is not enough to simply look at what popular culture signifiers are used in political memes. We must also learn to recognize and address the uneven distribution of available referents in popular culture that would have salience for a wide audience. Popular culture-based memes may be flexible in their interpretations and uses, but they are constrained by the cultural resources available. In the 2016 election, this affected the kinds of memes that came to represent the three major candidates, Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and Bernie Sanders. The uneven distribution of male and female speaking characters and lead characters that Smith et al. (2018) observe is replicated in the uneven diversity of positive popular culture referents in the three candidates' memes.

[4.2] Positive Hillary Clinton memes most frequently depict her using the same few media figures. Princess or General Leia, Rosie the Riveter, Wonder Woman, and (occasionally) Supergirl appear in memes, where Clinton is shown wearing the characters' most iconic costumes and in the most iconic poses. This small constellation of Clinton/character crossovers had wide enough circulation and acceptance that a variant of each appeared outside of memes in merchandise and cartoons. Interestingly, two popular characters that Hillary Clinton was frequently compared to in the press (Leslie Knope from Parks and Recreation [2009–15] and Hermione from the Harry Potter franchise) did not appear to be used for face-swap memes with Clinton. This key absence points to the significance of what texts may be popular with meme makers and how factors like age may preclude some cultural connections from being considered suitable material. While Wonder Woman and Leia are depicted as young women, they originated during the youth and early adulthood of baby boomers, so they belong to an older generation than Hermione. Further, the Wonder Woman film was released in 2017, so most memes in my sample depicted her in illustrated form, perhaps avoiding friction between her youthful, sexualized embodiment by Gal Gadot and perceptions of Clinton.

[4.3] My sample ultimately did not include a large number of pro-Trump media-based memes, because as someone who is already a popular culture figure, Trump often features as himself. However, those that I did encounter draw from a wider variety of referents and tend to share some key attributes: hegemonic masculinity, independence, and physical strength. Trump appears most predominantly as superheroes: Captain America on the battlefield holding a shield with "Make America Great Again" beneath it, a pumped-up Superman (an image repeated on an inauguration button), Spider-Man wearing headphones while swinging above a city, Batman running through the streets alongside Ted Cruz as Robin. These characters are all symbols of righteousness and heroism—notably heroism that works outside the law. Like Trump, they alone can fix it. Notably, although Jimmy Kimmel's short video casts Trump as Iron Man, he appears most frequently as Captain America, a character intimately tied to patriotic Americana (figure 4). Significant here is the sheer number of superheroes pro-Trump meme makers have to select from. These choices can be understood as having particular significance in light of the way that Trump is constructed through a lens of hypermasculinity—an alpha male and a cowboy (Penney 2017).

Figure 4. Composite image of four separate superhero memes: Wonder Woman, Captain America, and Superman.

[4.4] However, despite Bernie Sanders's very different public persona, he too frequently appears as this same set of superheroes, indicating that although a candidate's specific attributes may affect the kinds of crossovers used in memes, demographics alone are sufficient for this large library of superheroes to be applied to both Trump and Sanders. The fans of both candidates can choose among many examples of male heroes to select those most visually suited to memes or those that carry appealing connotations, such as Superman's association with heroism behind a facade. Hillary Clinton fans have far fewer cinematic superheroes to choose from that the average American would be familiar with. As a result, there are fewer connotative associations to be activated or to avoid; further, few images exist that do not include stereotypically sexualized bodies for her face to be added on to.

[4.5] Within a single media text, the plurality of heroic male models allows meme makers to construct male political candidates through several alternative frames while limiting images of female characters. Across the abundant Star Wars-themed memes, Clinton, with a single exception, appeared only as Leia when positively framed, whereas Trump appeared as Han Solo, Sanders as Luke Skywalker, and both appeared as Yoda and Obi-Wan Kenobi. This allowed meme makers using Star Wars images to tell many more stories about the male candidates, depicting them as youthful warriors in battle, cowboys, wise advisors, and moral guides. The "Bernie Wan Kenobi" meme grew to encompass multiple functions and subgenres, the core of which was an emphasis on Bernie's quiet heroism, his unique knowledge of evil, and, most frequently, the fact that he is "our only hope." Bernie Sanders is cast in the widest variety of roles of any candidate in my sample. He appears as all the major superheroes that Trump features as, emphasizing heroic masculinity, but he also appears, among others, as the wise wizards Gandalf and Dumbledore, the mad genius Doc Brown, and the roguish Robin Hood. Sanders could be imagined in the highly physical alpha male characters central to Trump memes as well as in characters whose roles were the knowledgeable guide or the orchestrater behind the scene. Some character face swaps, like Doc Brown, focus on his physical appearance; however, most focused on his presumed ability to create a better world, either directly or in the role of mentor or guide (Penney 2017). Sanders is even able to cross into a celebratory cross-gendered appearance through a variant of the "Birdie Sanders" meme, which riffs on a campaign event during which a bird landed on Sanders's podium. This moment was taken up by Sanders's campaign as an iconic moment that implied the extent of his appeal and created a halo effect around the candidate. In popular culture-based memes, this translates into a comparison between Bernie Sanders and Snow White, whose goodness is represented by how she is beloved by woodland animals. Face-swap memes substitute Snow White's face for Sanders's, who is shown sitting among a group of adoring animals; a variant adds Sanders's signature hair and glasses to the animated character. Clinton, by contrast, does not appear as a Disney princess in these memes, perhaps because the problematic politics of these characters would be more clearly activated with a female candidate, or because the soft, youthful femininity inherent in a Disney princess would be a problematic match for Clinton's existing image (Campbell 1998; Parry-Giles 2014) and for the expectation that a female candidate would prove to have a strength and competency not associated with these princesses.

[4.6] Sanders has proven to be particularly flexible in the eyes of meme creators; he appears as traditionally or hegemonically masculine superheroes, as older leaders, and even as a Disney princess. The mutability and variety of depictions of Sanders are consistent with Penney's (2017) observation that Sanders is a blank slate for his fans because he does not talk about himself and is considered by some to be a "known unknown." His political message is relatively clear and forceful, but the image of the man himself proves to have a good deal of space for fans to write on. This is not simply a matter of fan enthusiasm or creativity. Rather, it points to the greater diversity of heroic masculinities available in the pop culture lexicon that may be seen as compatible with political leadership and with male candidates, who may culturally come with some presumed leadership attributes and who may be able to more readily subvert expectations. This pattern parallels what Moody-Ramirez and Church (2019) find more broadly in Facebook presidential candidates' meme groups. Images of Hillary Clinton appear to be more univocal, presenting her in a narrower number of ways than the images of Donald Trump presented him. The smaller number of positive archetypes for women in media may synergize with and enhance narrower images of women and women candidates more broadly.

[4.7] How a single media text's vocabulary is deployed to frame multiple candidates at once can demonstrate not only the ways in which the memetic discourse draws on a text's lexicon but also the ways in which they are limited; characters in the text can become problematically fixed in ways that characterize candidates in relation to one another. For example, while all three candidates sometimes appeared as the Joker from the Batman franchise, when one or more Batman character was in the meme, Donald Trump was almost always depicted as the Joker. Indeed, Trump became connected enough to the Joker that Mark Hamill began reading Donald Trump tweets as the Joker, a role he previously played on Batman the Animated Series (1992–94). So although Hillary Clinton appears multiple times as the Joker in my sample (and Bernie does so at least once), when paired with Trump, these candidates are recast. Because the Joker's nemesis is the hypermasculine Batman, this role invariably went to Sanders when he appeared with either Trump, or Trump and Clinton. Although meme creators were able to imagine Clinton as a male character in the world of Batman, when she appeared in a Batman-themed meme with Trump, she appeared as the villain Two-Face, not Batman himself. This fits into a pattern in which Clinton cannot be imagined as a male hero but rather must be depicted as a male villain, suggesting that the masculinization of a female candidate is in itself suspect. Wiggins (2017) features two variants of these memes, which he collected from Bernie Sanders's Dank Meme Stash. Notably, only one features Sanders. The other focuses on the often repeated model of Clinton as Two-Face and Trump as the Joker, with "Choose" typed beneath them. Memes and popular culture archetypes both rely on shorthand to communicate their messages. In this case, Trump is associated with instability and a desire for destruction, while Clinton is associated with duplicitousness. When present, Sanders becomes the hero. Arguably, this negative meme of Clinton is more powerful when applied to Clinton than Trump because it echoes cultural discourses surrounding her emails and historical news frames, thereby treating her as inauthentic and duplicitous (Parry-Giles 2014). Like Palpatine, whom Clinton also appears as, Two-Face is a man who appears righteous, but he is twisted by fate and desire for power until he becomes an untrustworthy villain. Popular characters are here used as shorthand for a set of negative traits that critics seek to attribute to a character. They do so not only directly but also relationally. We are asked to either side with Sanders (the only hero), or to evaluate whether the Joker or Two-Face is the bigger threat.

[4.8] A similar dynamic is at play in Star Wars memes. Here Sanders's strong association with Obi-Wan Kenobi affects the roles the other characters appear to play. Bernie Wan Kenobi is shown fighting Donald/Jabba the Hutt, Donald/Darth Vader, and even Kylo Ren. The last is notable because Kylo Ren and Obi-Wan Kenobi do not fight on screen—and cannot in the canon's timeline. Bernie as Obi-Wan Kenobi is therefore implicitly brought back from the dead to fight Trump, and to sideline or replace a female character, Rey, who could have filled this role. In the only image or video in my sample in which Clinton appears with Trump or Sanders in the context of Star Wars (a parody image called Shit Wars) in which she is not the villain, she appears as Leia in her slave costume, sexualizing her and choosing the moment in the series where Leia has the least power, while Trump appears as Jabba the Hutt and Sanders appears as Yoda wielding a light saber (figure 5). Despite the availability of Rey in the franchise's timeline, I was only able to locate one meme in which Clinton appears as Rey; in this case, she is seen running away alongside Obama and BB-8; she is not presented in the context of her leadership potential. Both Rey's age and the relative newness of the character contribute to the dearth of her use in Clinton memes, as does Rey's existence in a different era from Kenobi, Vader, and Jabba the Hutt (key figures for her competitors). The Star Wars lexicon has a limited but increasing number of female figures for identification, while its classic vocabulary provides ample opportunities to place men into the roles of hero or villain. The appearance of Sanders as several potential heroes battling Trump in multiple villainous guises contrasts with the appearance of Clinton, who, when placed alongside them as a passive Leia, brings us back to the limits that the available media text's lexicon places on memetic discourse.

Figure 5. Composite image of two Star Wars-themed memes.

5. #Bernthewitch

[5.1] If we think of the available language of a media text (or media ecosystem) as having a vocabulary made up of characters, places, and objects with particular valences or accents (such as villain, hero, desired, and disgusting), we have to consider the gendered imbalances that exist not only in terms of quantity but also in terms of trends within the available lexicon. The dearth of salient pop culture images to draw on in memes supporting Clinton contrasts vividly with the negative images of older women available for anti–Hillary Clinton memes to draw on, particularly images of the woman as abject—that is, women as witches and as grotesque. This ample vocabulary of "evil women" is supplemented by the willingness to depict Clinton as male characters when conveying a negative message, thereby reinforcing the association with villains as improperly performing gender (Griffin 2000; Li-Vollmer and LaPointe 2009). A wide variety of characters from both classic and contemporary films, both male and female, are deployed in critiques of Clinton and frequently frame her as threateningly abject.

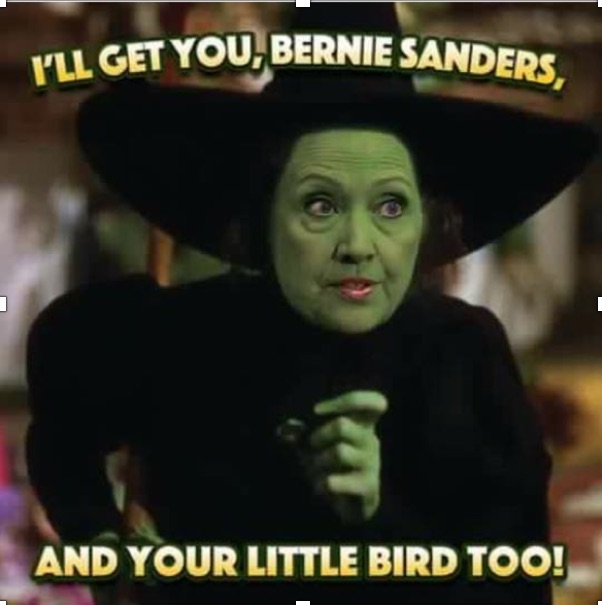

[5.2] In many cases, these character choices specifically activated existing tropes used to discipline women. A Bernie Sanders supporter posted a debate watch party on Sanders's website and titled it "Bern the Witch," and although the phrase received critique, it was widely taken up and used on merchandise like pins or shirts (sometimes completed with an image like Clinton riding a broom). This tag line makes explicit the animus behind the numerous images of Clinton as a pop culture witch. In my sample, Hillary Clinton frequently appears as The Wizard of Oz's (1939) Wicked Witch of the West. One variant synergizes Clinton with Birdie Sanders, depicting her as the classic witch with the caption, "I'll get you, Bernie Sanders, and your little bird too!" (figure 6). This meme, which appeared on a "Vote for Bernie in New York" page, casts Clinton not as a competitor (as the Captain America versus Iron Man memes did) but rather as the villain. Sanders in this formulation becomes the young innocent. Clinton also appears as several Disney witches, with her face swapped with that of the Evil Queen from Snow White (1938; both by meme makers and artists and illustrators), Maleficent (from the 1959 Sleeping Beauty) (figure 7), and Ursula from The Little Mermaid (1989). All three reinforce the association of Clinton with witches—a longtime trope used to discredit women and express fears of assertive or ambitious women (Miller 2018). However, they each activate a slightly different set of connotations and gender stereotypes. The Evil Queen is used to suggest vanity, and in some cases jealousy, toward Sanders, as in a case where she looks in the mirror and says, "What do you mean Bernie is the fairest?!," thereby activating the association of Sanders with the "pure" Snow White. In contrast, an Animorphs (1998–2000) meme shows Clinton transforming into Ursula, playing on associations of female witches with the grotesque and activating tropes that shame women for appearing less than thin and traditionally beautiful.

Figure 6. Hillary Clinton in greenface as The Wizard of Oz's (1939) Wicked Witch of the West: "I'll get you, Bernie Sanders—and your little bird too!"

Figure 7. Hillary Clinton in greenface as Maleficent.

[5.3] A wide variety of memes depict Clinton as abject by exaggerating her slightly overweight body into an impossible grotesque. Ursula is one manifestation of this, but there is a veritable smorgasbord of memes in this theme resulting from a Photoshop challenge using a single unflattering photo of Clinton. This image was used to make memes featuring everyone from Mama June to Tommy Boy, as well as characters more common to political memes such as Emperor Palpatine, Jabba the Hutt (figure 8), and Doctor Evil. Each of these memetic connections associates Clinton with villainy or with the physically grotesque. Many of these images treat her failure to conform to the thin ideal of hegemonic femininity as an expression of greater transgressions. These images associate Clinton's lack of sexual appeal for some onlookers, or sexual threat as expressed in merchandise like the Hillary Nutcracker, with both evil and abjectness creating images designed to elicit disgust. These images police Clinton as an "unruly woman" (Rowe 1995)—a woman who refuses to make herself small or quiet, and who is in these images depicted as a grotesque excess as punishment. Indeed, after Clinton was perceived as comparing herself to Wonder Woman after election, memes appeared in response depicting her as a morbidly obese and scantily clad Wonder Woman, disciplining her in a way Trump never was for his comparisons to Batman. The extent to which these memes are about shaming women for their appearance and connecting appearance to trustworthiness is laid bare in a variant of the plentiful Clinton-as-Palpatine memes. Such images depict Emperor Palpatine (this time without the traditional face swap) and the text, "A rare photo of Hillary Clinton without makeup." The use of Palpatine—a character who has become increasingly ugly through his interaction with the dark side of the force in the Star Wars universe—to undermine female politicians is seen throughout the 2016 campaign (figure 8), and it persists today, with Nancy Pelosi and Dianne Feinstein undergoing the comparison on Reddit. Similarly, female politicians Pelosi, Maxine Waters, and Kamala Harris all appear in memes as the Wicked Witch of the West.

Figure 8. Composite image of two memes illustrating the grotesque body via Star Wars memes: Hillary Clinton as Jabba the Hutt (top) and Palpatine (bottom).

[5.4] It is notable that many of these images depict Clinton as a male film character—something rarely seen in the positive memes featuring her. This is consistent with Smirnova's claims that "women seeking positions of authority in a patriarchy are often silenced or discounted by being deemed too masculine" (2018, 7). To some extent, Clinton's portrayal as these characters emphasizes an untrustworthy ambition in a way that defines her as both masculine and untrustworthy, even gluttonous, while also defining her as failing to perform a sufficiently appealing mode of femininity. Yet transformation of Clinton into the grotesque is as much a comment on her unruliness as a public figure who is perceived as aggressive and insufficiently feminine in her affect than it is her physical appearance. As Campbell (1998) demonstrates, Clinton's inability to sufficiently perform the rhetoric of soft femininity has engendered hate during her whole career. Many, like the images of Palpatine and witches, also activate existing frames of Clinton as inauthentic or conniving when she enters the public sphere (Parry-Giles 2014).

[5.5] The elements of disgust—both moral disgust and in some cases physical disgust—presented by these unappealing villains are also prevalently used in negative memes featuring Donald Trump. Trump, like Clinton, appears as Palpatine and additionally as Darth Vader, Doctor Evil, Gollum, and, particularly frequently, Jabba the Hutt. Election memes more broadly frequently draw on Trump's physical appearance (Moody-Ramirez and Church 2019), and indeed some variants of "Darth Vader as Trump" memes use Trump's signature hair, a gesture that serves to emasculate Trump by emphasizing his flabbiness or his age in ways that undermine his virility. This can vary by meme. Some memes featuring Trump as Jabba simply focus on him as disgusting in appearance, while others launch an explicit critique of his treatment of women. Smirnova (2018) observes how many of the memes that purportedly critique Trump focus on him as insufficiently masculine (emphasizing his vanity or implied subservience to Putin), noting that although these memes may attempt to undermine Trump, they do so by suggesting that he fails the standard of hegemonic masculinity associated with the presidency, thereby simultaneously reinforcing this patriarchal norm. Whether it is female politicians depicted as the Wicked Witch of the West, disciplining ambitious women as unappealingly aggressive and insufficiently feminine, or Trump appearing as the flabby and weak Jabba the Hutt, the characters used (and arguably the characters available) to represent villainy discipline both women and men through the idealization of hegemonic masculinity.

6. Heading to Hogwarts

[6.1] Within a single case study, such as the use of Harry Potter in political memes, several of the issues discussed above come into play: the available lexicon of the media texts, the impact that the other candidates' connections to specific characteristics have in fixing meanings related to a single text, and the ample tradition of memorable and threatening female villains. All three attributes may be seen in one of the most enduring images of the campaign: Hillary Clinton as the Harry Potter villain Dolores Umbridge, a McCarthyesque bureaucrat who works to undermine the great Dumbledore (typically cast as Bernie Sanders in memes) and who seeks to strip away the rights and pleasures of the youth of Hogwarts. Few media texts have the widespread salience and diverse fandom, particularly among millennials, that Harry Potter has achieved, so it is unsurprising that some of the most persistent media-centered memes of the 2016 election derive from this media text. In contrast to the fluidity that male characters from the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars enjoy, face-swap memes in the Harry Potter universe are generally relatively fixed.

[6.2] This fixity is particularly problematic in the equation of Clinton and Umbridge. Unlike Clinton's appearances as the Wicked Witch of the West, which involves significant distortion, there is little alteration of Clinton's appearance when she appears as Umbridge. Similarities in age, size, hair length, and use of pink in their wardrobe are apparently sufficient to fix the association of Clinton with Umbridge in memes (figure 9). This representation is particularly powerful because it activates both existing negative images of women as scolds, who stand in the way of both fun and heroics, and more insidious negative images of Clinton herself as a protofascist in disguise. The frequency with which this meme is used while eschewing other Harry Potter characters like Hermione, who appear to be too youthful, is telling. The size of a media text's lexicon of female characters is insufficient to allow for positive memetic use; the ages and appearances of female characters also become key in determining both the availability of positive and negative images for use in memes and the ways they may be fixed.

Figure 9. Harry Potter meme showing Bernie Sanders as Dumbledore, Hillary Clinton as Umbridge, Donald Trump as Voldemort, and Ted Cruz as Snape.

[6.3] This depiction is particularly sticky because two of Clinton's fellow presidential candidates are also firmly cast as Harry Potter characters in a large number of memes: Donald Trump as Voldemort and Bernie Sanders as Dumbledore (Wilson 2016). As noted in the case of Star Wars, representations of these candidates as each of these characters refer to one another both explicitly and implicitly, thereby reinforcing the entire constellation of references. In the Harry Potter universe, Donald Trump represents the unbridled racist evil of Voldemort, Bernie Sanders the wise and steadfast heroism of Albus Dumbledore (the more complex reading of Dumbledore as secretive and exploiting his young charges is often elided here), and Hillary Clinton the bureaucratic evil that for many may hit closer to home. Here again Clinton is cast as a witch and as untrustworthy; further, she is used in relation to two other popular culture characters in a way that supports two well-worn premises. First, which of these evils do you prefer, Voldemort or Umbridge, Two-Face or Joker? And second, once again, only Bernie Sanders (that old white guy) can save the day.

7. Conclusion

[7.1] Jeffrey Jones observes that in political discourse, "people talk with television, using its narratives as part of how the world is to be understood" (2010, 30). Political memes help make this dynamic of "talking with" media visible for analysis. However, they also demand that we consider the limitations of the language that media makes available for us to talk with and the way in which the inequities and injustices of old media are then replicated in new media. In a reflection on the digital dimension of the 2016 election of Donald Trump, Ben Schreckinger (2017) observes, "Veterans of the Great Meme War brag that they won the election for Trump." Although Schreckinger casts doubt on these claims, scholars have suggested that memes are significant. Wiggins argues that the memes on Bernie Sanders's Dank Meme Stash provide a clearer image of "the peculiarity of vitriol directed at Hillary Clinton and largely its absence about Trump" (2017, 203). Moody-Ramirez and Church (2019) trace scholarship demonstrating that memes can "change public opinion and promote social movements."

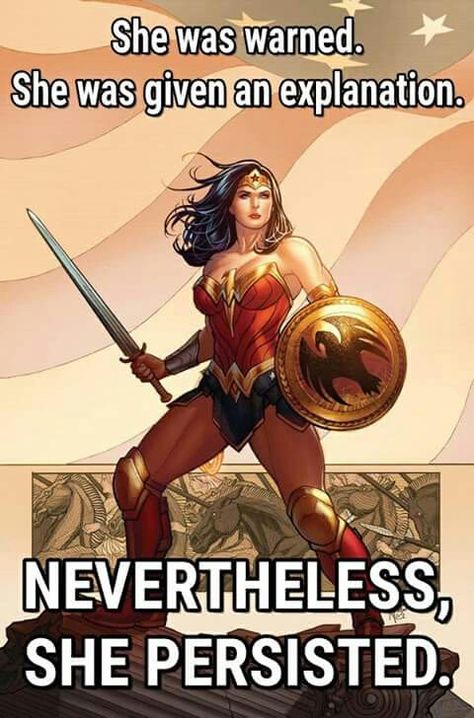

[7.2] Memes are a lingua franca used to discuss politics online, and popular culture is one of the chief lexicons used in their creation. Although the framing of candidates by political fans and antifans is important to shaping social media discourses like memes (Kohlemainen 2017), we must not underestimate the impact the contours of the popular media landscape have on these discourses. The history of popular entertainment media, particularly in regard to the genres most associated with fandom, is one that has long perpetuated inequities between the depictions of men and women as leaders—or indeed has depicted them at all. When women are shown as heroes, they are frequently the exception, not the rule. While in the last decade Sanders and Trump fans have been able to choose from over ten male superheroes who had led their own films, Clinton fans had only the promise that Wonder Woman was coming out soon. Not only are the available images of men and women that memes may draw from imbalanced but they also provide historical stereotypes of women, like the threatening witch. The relationships between characters within a text, which often include many heroic and villainous male characters and scant female characters (particularly older female characters), function to further delimit the ways in which women can be depicted, particularly given the cultural baggage these characters hold. The equation of women in power with villainy, and how this compromises the popular culture lexicon, is particularly influential. The power of this cultural trope is evident in the evolution of one of the few figures used in positive memes about Hillary Clinton: Danaerys Targaryen. While depicted positively in Game of Thrones at the time of the 2016 election, this icon of female leadership is transformed by the end of the series into a brutal, unstable tyrant.

[7.3] The 2016 election is now a memory, but as of this writing, the 2020 election is heating up, and already two of the initial slate of female candidates, Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris (who withdrew on December 3, 2019), have been depicted as witches at least once. As for their supporters? Well, we'll always have Wonder Woman (figure 10).

Figure 10. Wonder Woman meme.