1. Introduction

[1.1] In early 2009, science fiction fandom's online landscape erupted with discussions of race. A post regarding cultural appropriation on author Elizabeth Bear's blog sparked a wide-ranging conversation that soon became acrimonious, with professional science fiction and fantasy writers and fans of science fiction literature and media weighing in; discussions which had taken place within fannish subcommunities for many years gained a much broader reach (note 1). More recently, criticisms of Patricia C. Wrede's decision to set her young adult novel, The Thirteenth Child (2009), in an America empty of indigenous people have spearheaded new waves of discussion (http://linkspam.dreamwidth.org/tag/mammothfail) (note 2). Often the more widely read summaries of these debates have focused on what they mean for writers and aspiring writers who plan to represent minority cultures in their works. But what has their significance been for members of fan communities?

[1.2] Debates about racism and other forms of global structural inequality—seen as unproductive Internet drama to some and as a form of social justice activism by others—have increasingly shaped the public online landscapes of some sectors of science fiction and media fandom in recent years. This is a discussion among participants in these debates, primarily fans of color, about how discussions about race and fandom have shaped their experiences and politics, and of what the emerging movements mean for fandom and antiracism. The conversations took place informally at WisCon (http://www.wiscon.info) and have been transcribed, edited, and supplemented by e-mail discussion afterward.

[1.3] The participants in this conversation are as follows (some are contributing under their fan names, other under their legal names): Coffeeandink, Deepa D., Jackie Gross, Liz Henry, Oyceter, Sparkymonster, and Naamen Tilahun.

[1.4] Coffeeandink is a white feminist who sometimes blogs about science fiction, fandom, and race at http://coffeeandink.dreamwidth.org/. Deepa D. is a South Asian Indian woman whose public blog is http://deepad.dreamwidth.org/. Jackie Gross (ladyjax) is a black lesbian feminist fan living in Oakland, California (http://ladyjax.dreamwidth.org/). She's still bitter about Space: Above and Beyond being canceled by Fox. Liz Henry is a feminist SF/F fan and netizen from the San Francisco Bay Area, and is white, queer, and disabled, a Web developer, blogger, and translator. She blogs at http://badgerbag.dreamwidth.org/ and http://blogs.feministsf.net/. Oyceter is a Chinese American woman who grew up partially in Taiwan. She blogs about books at http://oyceter.dreamwidth.org/. Sparkymonster is a 34-year-old geeky, mixed-race (black and white), fat, queer, femme, feminist woman of color who brings her love of intersectionality everywhere she goes. She blogs at http://sparkymonster.livejournal.com/ and sporadically at http://www.fatshionista.com/. Naamen Tilahun is a 26-year-old geeky black writer and fan living in the Bay Area. He blogs in various places online, but his main home is http://naamenblog.wordpress.com/.

[1.5] The discussion was moderated and transcribed by TWC symposium editor Alexis Lothian, a white fan and academic who has written about fannish antiracist activism in both scholarly and fannish contexts. Her academic blog is at http://queergeektheory.wordpress.com/.

2. Changing the terms: Bingo?

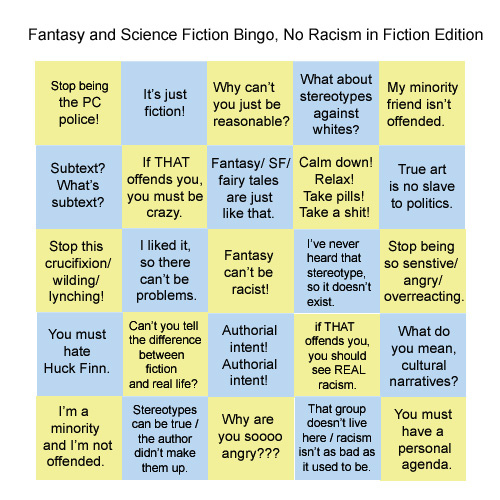

[2.1] Alexis Lothian: Online political discussions have produced their own kinds of transformative works. A genre that has become especially important in fan discussions of race has been the bingo card, where common arguments are debunked by a visual demonstration of how clichéd they are.

[2.2] Liz Henry: I've seen bingo cards in online activist discussions for many years. I have a collection in a Flickr set (http://www.flickr.com/photos/lizhenry/sets/72157612897466679/) that includes several race bingo cards as well as cards for anti-breast-feeding arguments, fat hate, and more.

Figure 1. Example of a bingo card: Fantasy and Science Fiction Bingo, No Racism in Fiction edition. Courtesy of Liz Henry. [View larger image.]

[2.3] Sparkymonster: I first encountered bingo cards in the feminist blogosphere, where they were explained on an amazing feminism 101 blog (http://finallyfeminism101.wordpress.com/).

[2.4] Deepa D.: Bingo cards have evolved as a shorthand for something that people have personally experienced. Without that personal experience, the bingo cards can seem unnecessarily simplistic and generic—almost cruel. A problem occurs when people are exposed to bingo cards without the experience of being socialized in the way fandom has talked about things. For example, I've had the meat-space experience of showing antiracist bingo cards to people who are not in fandom. People of color who weren't part of these discussions online had a sense of wonder and awe that people have come up with simple, clear language to explain all the diffuse experiences that have hurt them in various ways. They haven't had someone to do that for them—to say, "You're not alone. This happens so often that we can give it a name and a three-word term to put on a square." On the other hand, for white people who haven't seen those arguments happening, it's the reduction of something that's a personal experience to a pattern that they feel puts them into a mold. So I think that the value of bingo cards is layered according to who is experiencing them.

[2.5] Coffeeandink: It's interesting that the people of color in this discussion find value in the fact that the bingo cards don't explain, that they say, "You are too ignorant for me to talk to, your argument is not worth my energy and time." Because that's what's always made me feel ambivalent about them. What I really want is for each square to be linked to a wiki explanation of the argument and counterargument, so that if the person making the racist argument takes the initiative to click, there's an explanation available. But that again puts the burden on the person linking to bingo, the person of color, to be the educator, whereas it seems like people prefer to use the bingo cards as a protest against that expectation.

[2.6] Sparkymonster: I don't use bingo cards as a tool of discussion. But when I get so frustrated, angry, and hurt and someone says, "Ooh, bingo!" it breaks the toxic buildup for me. Humor, especially bitter humor, is really critical for helping me make it through these kinds of discussions. Laughing at the stupidity is one form of release.

[2.7] Deepa D.: What we're really talking about here is what people of color experience, and I want to bring it back to that. Bingo cards might be useful for white people, but they are important for people of color because they say, "What you are experiencing is not personal; you're not alone; this is part of a structure." It's important to recognize the parts of the pattern because then it ceases to be about one person; it ceases to be about one incident that can be forgiven and becomes part of an institution that cannot be forgiven.

[2.8] Oyceter: It's naming something. It's like L. Timmel Duchamp's 2008 WisCon guest of honor speech (http://ltimmel.home.mindspring.com/Duchamp-WisCon32-GoH-speech.pdf) about sexual harassment—being able to have the term, to say, "This is racism." To name some of the arguments we might find on a bingo card: this is white women's tears, this is the tone argument.

[2.9] Deepa D.: All this was revelatory for me because I realized I found strength through having pattern recognition. I was able to parse instantly what someone was saying, to not take it personally or focus exclusively on the details, but to see it as part of a pattern and classify it accordingly. So I don't have to waste time having a personal reaction. I can go straightaway into strategies to deal with a pattern of oppression. And a lot of people don't have that, because depending on where you are in a white-majority country, lot of people of color lack a supportive, educational network, especially if you are young and not in an activist community.

[2.10] Oyceter: Or if your family doesn't teach you to recognize those patterns.

[2.11] Deepa D.: In education, teaching people to recognize patterns is a basic pedagogical tool; it's how we learn to understand math, to recognize cause and effect. Unless you can recognize patterns in racism, you won't recognize institutional racism for what it is and how it manifests in individual people.

3. Manifestations: The tone argument

[3.1] Alexis Lothian: A bingo card definition of the tone argument goes something like, "You are alienating people with your anger. If you would only explain your criticism politely, everyone would understand your point."

[3.2] Oyceter: When I started to get involved in discussions of race in fandom, I thought that the people of color calling people out for their racism were too mean and snarky. Then, as I got more involved, I realized that the snark is self-protection against the ignorance and abuse that comes up when white people are asked to confront their racism. Sometimes all I can do is use cat macros because I am wordless.

[3.3] Coffeeandink: I noticed the phrase "a civil conversation" in the most recent rounds, coming from men in particular, from white people who hadn't previously engaged in discussions about race with people of color or in an antiracist space. It's another version of the tone argument, the vocabulary argument. It ignores the subjectivity of reading tone and the unequal standards applied to people perceived to be white versus those who are perceived to be of color. There's just no way to politely challenge privilege, because the privileged party defines politeness. The "civility" of the conversation is defined by the vocabulary used or the amount of ritual deference offered, not by whether or not someone just claimed that by virtue of your race, you were incapable of reasoned argument.

[3.4] The thing that blew up the tone argument for me was the treatment of Zvi when she criticized a Harry Potter fan community for using the term miscegenation without understanding its history (note 3). She was patient and civil, yet people were saying she was uncivil—even insisting that her icon was inappropriately violent because it said, "If you can't be educated, you will be killfiled" (that is, summarily discarded, without reading).

[3.5] Deepa D.: The tone argument is important because almost all of us have made it—at least in our heads and sometimes, unfortunately, online—about another person of color. Because we have hope! We have hope that being polite, being generous, being kind, or explaining something in the right way, works. We are used to treating individuals as individuals and persons, but talking about the tone argument again reinforces that it's a pattern: this is a systematic thing, not a one-person thing, and systems can't be dismantled by politeness. You can dialogue politely with an individual, but you don't dialogue politely with an institution of oppression. You act disruptively with an institution of oppression—even if it's nonviolent anarchism or nonviolent protest. You disrupt, you do not dialogue.

[3.6] Oyceter: And I think that's specifically why tone comes up: it's a form of systemic oppression. To make the tone argument is to say don't be violent; don't connect; talk on this individual level, and let me break alliances up into individual pieces.

[3.7] Sparkymonster: It's also a way for white people, or privileged people in general, to deny all responsibility by saying, "I will only educate myself if you will say it the perfect way." This is something I struggled with for a long time. I would say, "Have you heard of this thing called white privilege?" and people would respond, "You are so mean and racist." I would think, "What did I say?" But then I realized that it doesn't matter what I say—if someone is going to have that reaction, they will have that reaction whether I cover it with bunnies or tell them to die in a fire. I started to comment with lists of links because I realized I don't need to restate these articles, just get people to read them. I've had people say I'm being mean and dismissive, that I'm treating them like they're stupid. But if I'm giving you links, if I'm bothering to comment at you, I probably think you're someone who can have a discussion with me. If you flip out in response, you don't have the same respect for me.

[3.8] When people describe fans of color challenging racism as a mean, undifferentiated horde, they're not seeing how so many are being scrupulous and polite. My response is, "Who are you talking about? Stop smushing us!" There are people using many different kinds of strategic arguments, and they can include anger, which is a powerful and important tool.

4. Manifestations: Race and white femininity

[4.1] Alexis Lothian: The intersection of race and gender is crucial to a lot of the terminology that comes up in discussions of race in fandom, particularly because much of the discussion takes place in online spaces that are dominated by white women.

[4.2] Sparkymonster: The common experience that gets shorthanded in bingo card terms as "white women's tears" is when you're talking about race and a white woman's response is, "When I was in high school these black girls were so mean to me!" or, "When you talk about race it makes me cry!" And then suddenly everyone is comforting the white woman instead of continuing to discuss race.

[4.3] Oyceter: It becomes about the white woman's pain for being jumped on for saying something racist, or about her pain from looking at the pain of an oppressive situation.

[4.4] Deepa D.: One of the purest, most crystalline forms of white women's tears comes when white women are genuinely upset about racism.

[4.5] Oyceter: And they aren't strong enough to take it. They think women of color are strong enough to deal with racism, but white women aren't. I would like to link to Chrystos's poem "Those Tears" (http://resistracism.wordpress.com/2008/05/21/those-tears/), about the tears of a white woman who was challenged for trying to enter a "women of color only" space, which may be where the term comes from. Some women of color then created the specific term "white women's tears" as a reference not only to the poem, but also the term "white women's syndrome" (http://www.racialicious.com/2008/08/27/white-feminists-and-michelle-obama/#comment-917278) as a way to codify patterns of white women's behavior about racism and sexism in general. Terms are shorthand for this giant intersectional thing: how white men "chivalrously" spring to the defense of white women "under attack" from women of color, and the entire system in which white womanhood is set up as the example of womanhood and how that erases women of color as women. And it's all there in three words as "white women's syndrome."

[4.6] Liz Henry: It's also connected to missing white woman syndrome (http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p_mla_apa_research_citation/2/3/1/3/3/p231334_index.html) where a white woman goes missing and white men everywhere rush to the rescue—but black women go missing and aren't given any of the same attention (http://www.whataboutourdaughters.com/).

[4.7] Jackie Gross: Another pattern that all this connects to is the nice white lady—as demonstrated in the MADtv skit (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZVF-nirSq5s). It's the trope of the white woman who comes to the benighted inner city youth to save them from themselves, in movies like Dangerous Minds (1995) and Freedom Writers (2007).

[4.8] Sparkymonster: To bring us back to Wrede's The Thirteenth Child and its erasure of Native American people, in some ways, this reminds me of the reservation school system: "Kill the Indian and save the man" (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4929/).

[4.9] Deepa D.: There's an explicit link to missionary societies. It's easy to criticize missionaries who went out and tried to convert people to Christianity, but they were supported by women who stayed back and were nice and did social charity work, had sewing circles, raised money to send to the heathens. Nice is an important term because, much as Jane Austen deconstructs in Northanger Abbey (1817), nice is small. Nice says that what you are doing is not aspiring to greatness, just everyday goodness, and that provides an easy lens to say that expecting it is not demanding heroism, but demanding common decency.

[4.10] Without power differentials, the obvious answer to the question "shouldn't we all be nice?" is "yeah, sure." But when you bring race back in, it looks different. A white person being nice to a person of color is a privilege and a condescension that they can choose to bestow or withhold, while for a person of color, being nice to a white person is a chore and a duty and in many cases a safeguard that we have to undertake for our own protection. It's pretty telling that while the mistress can be very "nice" and "kind" and "patient" to and with her servants, the powerless perform the same behaviors and courtesies as a duty and job.

5. The landscapes of fan communities

[5.1] Deepa D.: The fannish demographic is implicated in the terms we use especially when we talk about gender. People who self-identify as female are the majority participants in the culture of transformative fan works based on media, so it's acceptable to carry an assumption that fannish space is a different space for using gendered words. It's good to deconstruct that, but the casual use has to be from a female-dominant space, as opposed to the larger context where the default is male. For example, I use the word pretty as a compliment for men online in a way that routinely raises eyebrows and disapproving reactions off-line from men. I'm also much less bothered by terms like bitchy and slutty and hysterical when I know they are being used among women, although they can still undeniably be weapons we use to hurt each other. Another telling example is that fandom, as comprising women, immediately understands the power of the phrase character rape, while it does not so swiftly regard the words colonial or Oriental with equal visceral horror, even though the effects of rape and colonialism have been equally scarring on women of color.

[5.2] Oyceter: That's very different from science fiction and fantasy (SFF) book fandom, which is mainly male. That was part of the miasma around the RaceFail (note 4) debate: the old boys' club of SFF book fandom that led to the dismissal not only of people of color but also of LiveJournal. They had the idea that LJ is full of hysteria and shrieking, and they asked, "Where are the rational people in this discussion?" That's very gendered.

[5.3] Coffeeandink: Another difference between the book and media fandoms is that book fandom is filled with aspiring writers who want to make a living from their work, while media fandom isn't about making a living at all. Status in media fandom isn't based on whether you make money from your work.

[5.4] Oyceter: I think there's a greater distance between creators of media in media fandom and the fans and that allows for a flatter fandom, whereas in SFF book fandom, I think that there's less of a distance between creators and fans because it is easier for SFF book fans to become SFF book creators than it is for media fans to become media producers—which in some ways is cool, because fans can influence professional production, but it also creates a more hierarchical structure.

[5.5] Deepa D.: In media fandom, social capital is policed quickly, because it's the only kind of status writers have. If your fic is called racist, you lose a lot of social capital, while Elizabeth Bear can lose that social capital and gain financially from the additional sales the discussion brings her.

[5.6] Sparkymonster: On the one hand, if everyone agrees your fic is racist, then media fandom can trash you in 4 seconds. But on the other hand, there is also a weird forgetting, where people change their user name or the memory of the trashing just fades with the passage of time. So I'll see someone who got trashed for sexism, transphobia, or racism pop up under another user name, which is very easy to do—and sometimes people remember, sometimes they don't. I think that's part of why people can get so defensive in media fandom—because they are so caught up in their social capital.

[5.7] Deepa D.: While fic is archived and vids are shown publicly, in fandom, there is also always the idea that it's possible to rewrite things. Fans who are involved with the production of transformative works are used to discussions where a community can constantly reinvent itself, where it can self-correct if things are going wrong. You can edit something that you've posted online.

[5.8] For SFF, it's a case of, "We published a book that was edited a year ago, written 2 years ago, and it's done. What do you want us to do about it now?" It's ironic and ridiculous in some ways, but the fact that we know we can change things makes us more responsible about changing things. We recognize that things are permanent when they're on the public record, that anyone can take a screencap and save it, but because things are constantly changing, it's our duty to document that change. We recognize that we self-correct, that sometimes that's for good and sometimes for bad, and we try to acknowledge that power and create a structure that takes account of it. However, in a lot of SFF, there's a sense that there are real words on dead trees that are set in stone and can't be changed, as opposed to empty words online that are a great publicity tool or ego massage, but that writers do not need to be held accountable for.

6. Racialized spaces and erased histories

[6.1] Coffeeandink: I'd like to talk about the gendering and racialization of space, both physical and virtual. Multiple white people posted about being frightened by RaceFail, that it made them afraid to write about people of color. My take is that this is a conversation that shouldn't be had in a public space. By having the conversation in a public space, he is marking this public space as a white space, where the white guy gets to announce that his racial anxiety is a concern everyone, especially people of color, should focus on. It's an assumption that all space belongs to me and my concerns: it's private if I want it to be, even if it's public and online, so it's outrageous if someone comes in and disagrees, yet this space is public and I can say what I want. People being checked on their privilege repeatedly have defensive reactions and have conversations about it in public—crying white women's tears. These reactions are natural—there's nothing wrong with the emotions, but in having them publicly, you're saying the entire world should be focused on you.

[6.2] Sparkymonster: It's a way for people to affirm their status as a nice white lady.

[6.3] Coffeeandink: It's a way of affirming the public space is white, as a space where white concerns are paramount.

[6.4] Naamen Tilahun: A lot of fans have a different idea of safe space than I and a lot of activists do, I think. Safe space for me has never included the idea that you won't be offended, won't be hurt, won't be angered, won't leave crying. From the activist spaces I was in, safe space was a way to air grievances, check in with each other, and discuss our differences. Fans, for some reason, seem to look at safe space as a place where they won't be challenged or asked to explain their actions and thoughts—just the opposite. A safe space is where you should be challenged, where you have to explain yourself. I remember the Queer Alliance at my undergrad school having a discussion on whether we were going to take a stance on marriage equality or not. I and one other member were against an in-favor stance for the organization, specifically because of our feminist issues with the institution of marriage. There was a knockdown, drag-out fight. We were challenged on some sides pretty harshly for our stance. It was uncomfortable. I had to explain myself, and eventually some of the other members and I simply had to agree to disagree. Safe space is where it's safe to call someone out for something they said or did. Safe space is not yet another place where your privilege is supposed to protect you.

[6.5] The comments David Levine and other people made about not wanting to write characters of color any more show me that if you can give it up that easily, you were never invested.

[6.6] Oyceter: It's those people who say, "You people of color are making me rethink antiracism!"

[6.7] Naamen Tilahun: If what I say makes you rethink equality, then you were never invested in that equality to begin with. Fighting for equality isn't easy—it has never been easy—and if you are trying to be an ally in any situation, you will inevitably get called out.

[6.8] Oyceter: A horde of people kept popping up to say that they marched in the 1960s and that they knew the civil rights movement. They refused to accept the terms being used in the contemporary antiracist movement.

[6.9] Jackie Gross: It's the same as when white feminists use Audre Lorde's "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House" essay (1981) to signify how down they are.

[6.10] Sparkymonster: Lorde's essay was written because she was invited to speak at the Second Sex conference in 1979 at New York University, where the speakers were almost entirely straight white women. Lorde spoke directly about straight white feminists who cling to racist and homophobic power structures because they don't want to give up their privilege. It depresses me that 30 years after she wrote this essay, feminists still put together conferences of white women talking to other white women. Our viewpoints are still being ignored. I don't think feminists have really dealt with Lorde's letter to Mary Daly (http://tinyurl.com/lorde-daly-letter), which is a critique of a white feminist co-opting bits of African culture for her own purposes, while ignoring the input and voices of actual African and African American women. Mary Daly never responded publicly to that letter. I'm still appalled that Daly dismissed Lorde, and that Daly's acts of cultural appropriation are not part of the dialogue around gyn/ecology.

[6.11] Naamen Tilahun: During RaceFail, people would often not link to posts critiquing racism. They would pick and choose what people of color had said and use it to prove their point, but they wouldn't include what came before or after. That's the same way Lorde gets used.

[6.12] Deepa D.: Everyone here has commented on RaceFail, and we're all familiar with this level of detail in the history of antiracism. And in online discussions we've all been accused of being nonexistent or ignorant or too academic or not academic enough. We participate in fandom as equals, which means we're no more but no less than any other fan. As fans, we accept that there are different viewpoints—we're all online talking about Spike and Buffy or whatever, and we do that as equals. We give that respect to other fans automatically even though, when it comes to racism, we are the experts.

[6.13] Jackie Gross: I'm 43, and part of me remembers this same conversation from 1986. Women of color walked out of the '86 or '87 National Women's Studies Association meeting because they were angry about being tokenized. This is not new. In feminist spaces, it stuck and was documented in books and articles. People remembered. There were articles in newspapers, and there were books like Barbara Smith's Homegirls (1983), publishing houses like Kitchen Table Press that documented all of this.

[6.14] Deepa D.: To bring this back to the Organization for Transformative Works and its focus, media fandom has done that archive work. There are entire communities dedicated to what can be talked about in which space, providing links to past debates that have shaped the conversation in fandom. International Blog Against Racism Week (http://community.livejournal.com/ibarw) is just one example. In RaceFail, Rydra Wong rose up to record what was taking place, linking to every part of the widespread conversation. Then Naraht rose up in her place for the next round. Because they're burning out, we now have a community called Linkspam (http://linkspam.dreamwidth.org/).

[6.15] But we have to talk about the fans of color who have been participating in fandom for the last 10 or 15 years—they're not activists.

[6.16] Sparkymonster: Yes, people like Te (http://teland.com/remember/) and Stormfreak, an early voice in comics fandom who was vilified by Fandom Wank (http://www.journalfen.net/community/fandom_wank/) but in retrospect spoke a lot of truth. Witchqueen, now known as Zvi, and Witchwillow, now known as Avalon's Willow, were powerful influences on me. One of Zvi's posts from 2002 (http://zvi-likes-tv.livejournal.com/2385.html) really struck a chord and got me thinking/speaking.

[6.17] Deepa D.: They haven't filed a grant, they haven't got support to do activism; they're just people who want to be fans and who've laid the groundwork by fighting again and again in spaces where they shouldn't have had to fight in the first place. They've made it safer for us to speak up and find each other. In the fandom versus professional SFF discussion, we can feel pride in the way fandom in general has policed itself. But that was at the cost of fans of color, who were burned out, hurt, not paid, and not rewarded. They paid the price by having to retreat from something they love.