1. Introduction

[1.1] On August 6, 2016, a group of twelve individuals was banned from Governador Magalhães Pinto Stadium, popularly known as Mineirão, during a women's soccer match between the United States and France. Nine of these individuals were wearing T-shirts with a single letter stamped on each shirt. Together, the shirts composed the phrase "Fora Temer" (or "Out Temer"). Some carried posters with messages such as "Come Back Democracy" (Betim 2016) (figures 1 and 2). Political pamphlets or mosaics of this nature and with similar content were displayed in various competition venues throughout the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. On the same day, during the archery finals in the Sambodrome of Rio de Janeiro, where carnival samba schools usually parade, a sports fan was removed from the bleachers by National Security Forces agents, after supposedly yelling the very same "Fora Temer" expression during a moment of required silence (Romero 2016). Similar cases were reported on social media and by alternative media. In all these episodes, the issue of freedom of expression was put into focus, although it was generally minimized by mainstream media with a reference to an International Olympic Committee (IOC) directive prohibiting political and religious demonstrations at the Games, the so-called "Rule No. 50." The protests, of course, relied on the visibility of media broadcasts to audiences around the world.

Figure 1. Group of sports fans protesting against the then-acting president Michel Temer during a women’s soccer match in Rio 2016. The individual letters on each shirt combine to create the phrase "Out Temer." Source: Congresso em foco. Photograph taken by Mãdia Ninja, 2016.

Figure 2. The same group of sports fans raising another protest phrase, this time in English: "Come Back Democracy," in reference to what has been claimed by some sectors to be a parliamentary coup that took place in Brazil against president Dilma Rousseff. Source: El País Brasil. Photograph taken by Mãdia Ninja, 2016.

[1.2] In the field of Social and Human Sciences, research that emphasizes the relationship between sports and politics, in its most varied aspects, has been growing significantly in the last fifteen years. The relationship between sports and politics, especially the uses of sports by authoritarian regimes and also the role of sports in the fabrication of a national or collective identity (Melo et al., 2013), has gained prominence. Similarly, literature on feminist sports activism and gender inequalities (Cooky 2017), black athletes' participation in politics (Marston 2017; Edwards 2017), and other topics have grown in importance. Despite that fact, little or nothing is being produced on the relation of sports fans and politics, especially in respect to the Olympic Games. The analyses remain focused either on national and collective identities or on athletes' activism. Organized sports fandoms is also a topic of discussion (see Hollanda 2017), but it is usually restricted to media or violence studies. Although it is possible to map a few studies on political activism covering organized soccer fans in stadiums (Hollanda and Florenzano 2019), when it comes to unorganized or casual fans, it is hard to find other works.

[1.3] The main concern of this essay is to address this literature gap, presenting a theoretical approach to sports fandoms' politicization in the context of mega events such as the Olympic Games. Mega events are events of huge dimensions, like sports events (World Cup, Olympic Games, Pan American Games), music festivals (Woodstock, Lollapalooza, Coachella), or religious events (World Youth Journey), which generally imply logistical expectations, economic and social changes, infrastructural legacies for the hosts, and media attention (Müller 2015). Having recently experienced hosting sports mega events, emerging countries (like Brazil, Russia, China, and South Africa) have been the stage for several protests and demonstrations against corruption, social inequalities, and gentrification of urban spaces. Therefore, these countries may be seen as the natural empirical laboratory for the debate on sports and fan activism.

[1.4] The remarkable process of commodification of the Olympics began more than four decades ago during the management of Juan Antonio Samaranch, then head of the IOC (Boykoff 2011), in response to 1968 black athletes' protests and 1972 terrorist attacks. The organization not only worked to increase the value of the Olympic brand, which had the effect of raising the costs of organizing the games, but also favored nondiscretionary acts by local authorities in the expectation of containing the combination considered to be pernicious between politics and sports. In this way, as a major stage for visibility and political activism, the Olympic Games are the concern of a significant number of recent studies on the theme (Boykoff 2017; Hong and Zhouxiang 2012; Cha 2010; Lenskyj 2017; Henderson 2009; O'Bonsawin 2015). But, once again, the majority of these studies emphasize athletes' activism. At best, some of them, especially the ones that examine the 2008 Beijing and 2012 London Olympic Games, center their attention on isolated protests lead by activists representing social movements during the games, but none of them consider protests performed by ordinary citizens inside sports venues.

[1.5] Here, facing a scenario of politicizing sports events (Vimieiro and Maia 2017), we intend to discuss cases of protests against then-acting president Michel Temer during the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, as well as to understand how the IOC and other entities evaluate political manifestations that occur during the Games. Our main hypothesis is that the protests in Brazil in 2016 were characterized mostly as mediatized demonstrations, performed by individuals or small groups, always embodying a political performative play.

[1.6] Before these considerations, the present paper aims to (1) understand how sports fans use resources from sports fandoms to perform political claims, (2) infer how political activists have been attentive to how they can strategically appropriate the logic of media in sports mega events to capture the awareness of civil society and political authorities, and (3) analyze how these claims have been treated, confronted, or silenced by the mainstream media, sports authorities, and government agents. We are particularly interested in observing how it is possible to understand the scenario of political protests during the 2016 Rio Olympic Games from the perspective of mediatization of politics; how the media ecosystem treats these episodes; in what sense the protests during the 2016 Rio Olympic Games are similar to or different from other political demonstrations; and, last but not least, what are the internal contradictions present in the speech of Olympic committees and public authorities regarding the relationship between sports and politics according to the ideals of Olympism.

[1.7] To pursue these objectives, we have undertaken an exploratory research strategy that combines a historical mapping of protests at stadiums and venues of sports competition, as well as news coverage and social media about the 2016 episodes. Though one cannot speak on political fandoms in a strict sense, the casual sports fans we analyze here are undeniably using their condition as fans to politicize some issues and arenas. We are aware that Olympics spectators do not necessarily fit an understanding of fan behavior, as they generally do not belong to a particular sports fandom. Despite that fact, protests like the ones presented above clearly appropriate a sports fandom repertoire for rooting together, using uniforms, bringing banners, and shouting chants and command words. Furthermore, when it comes to events such as the Olympics or World Cup, we need to reconceptualize the usual understanding of fandoms, in order to include national fandoms joined by casual fans in special circumstances. In Brazil, for instance, it is very common that even people who do not like soccer become fans only during the World Cup. Additionally, these fans do not fit adequately under a traditional political protestor label, for they are not militant nor do they perform their demonstrations in more than a casual behavior while watching the games—which is a distinct change from protestors raiding the field during soccer matches as did Pussy Riot members in the 2018 Russia World Cup finals. This paper focuses its discussion on this casual sports fan activism, without forgetting that there may be plenty of other sports fan activism resources and repertoires.

[1.8] The article is divided into five topics from this introduction. In the first one, we begin with a review on the literature that deals with the relations between sports and politics, from the treatment of sport as a component of national identities (Hobsbawm 1984; Sigoli and De Rose Jr. 2004) to its instrumentalization through public policies or even as a form of political propaganda (Drumond 2013). Next, we discuss political activism during the Olympic Games. Then, we focus on our theoretical framework, presenting three distinct vectors of this debate: the fandom, the political play, and the spectacle. Finally, we bring some contextualization to the 2016 Rio Olympic Games and to Brazilian demonstrations during the Games.

2. Sports and politics

[2.1] History, social sciences and communication have become invested with greater importance recently in the transdisciplinary interface of sports studies. This development is analyzed by Melo and Fortes (2010), who point out that despite the significant increase in investigations, sport still suffers from a lack of academic prestige.

[2.2] It is important to emphasize that in contrast to what different sports entities convey (and also with the understanding of common sense), sports and politics are broadly associated categories, from the construction of sports public policies to the political use of sports by governments and social movements. In this regard, Drumond (2013) reminds us that there are many political regimes that have used sports as propaganda for their governments, the most commonly known being the Nazi German spectacle during the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games and the Soviet Union's intense investment in sports. Magalhães and Cordeiro (2016) analyze the Brazilian Military Dictatorship (1964–1985) and the uses that the regime made of sport, with one of the most famous episodes being the exploitation of the 1970 national soccer team as ad-boys of the dictatorship and the firing of coach João Saldanha, a communist party militant, on the eve of the World Cup, after he had reported torture and repression in the country.

[2.3] When it comes to sports studies, scholarly literature in Brazil is mainly concerned with soccer, generally understood as a tool of national identity and cohesion, and as an arena of social mobilization and political struggle. In this regard, there are various investigations concerning the importance of clubs, local and national teams, and events such as the World Cup as a kind of social party in Brazilian culture. Lately, a particular theme has grown in terms of research interest: organized fans and their relationships with the stigma of violent behavior, as well as spaces of sociability and for political action. Hollanda's work (2017; and Melo 2012), for instance, has been dedicated to reflecting sports fandoms from an oral history perspective. He interviewed not only leaders of the fandoms but also state authorities that have been trying to control and monitor organized fans' activities, in order to reduce violent episodes. His study discusses the growth of these fandoms, their criminalization and stigmatization as violent groups, and state actions to prevent fights (Hollanda and Reis 2014).

[2.4] Organized sports fandoms are an expensive subject for this paper. However, we do not want to deal with the subject of the stigma of violent behavior in this paper. As we will discuss later, Brazilian sports fandoms, especially within the context of soccer, have a specific meaning for organized fandoms. They are formal associations, sometimes even professional associations, that support their teams going to the stadiums, singing chants, using uniforms, and posing with large banners. Soccer clubs usually reserve some of the tickets for these fandoms. And some fandoms develop an intense rivalry with others. That's why most of the discussion on this subject by scholars and the media focus on violence (Hollanda and Melo 2012). The mega event fan is distinct from the common organized sports fans—although members of organized fandoms can be present as part of the audience at the World Cup or Olympic Games as well, most of them are casual fans.

[2.5] Richard Giuilianotti proposes to analyze four ideal types of sports fans: fanatics, followers, fans, and flâneurs. Analyzing the process of hypermarketing experienced in soccer in recent years, he argues that this dimension, associated with spectacularization, impacts the ways in which fans cheer and also the identity formation of new types of sports fans. These categories do not account for precisely what we understand as the fan-activist or more specifically the fan-protester, the one who goes to the stadium not only to root for a team from a sporting point of view but also for a political cause. How is this fan different from the others? Our premise is that we can find expressions of sports fan-activism in each point on Giulianotti's typology, for we must analyze this matter using a double axis perspective, taking into consideration the fan engagement both in sports and in politics. Thus, the casual sports fan-activist is the one whose behavior is driven by a citizen-marketer permanent practice (Penney 2017) without losing contact with a casual and episodic interest in sports entertainment. But are sports fans allowed to politically demonstrate? Doesn't politics defile sports somehow?

3. Sports and activism

[3.1] The 2016 Rio Olympic Games were not the first and will not be the last to become a showcase for articulated protest groups. In the 2012 London Olympic Games, for example, demonstrators played badminton in front of the main Adidas store in the city, a criticism of labor exploitation by the multinational, one of the sponsors of the mega event (Almeida 2012). In 2008, Tibet intensified its protests against annexation to China on the eve of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games (Melo 2008; Cha 2010). The 2016 Rio Olympic Games, however, brought an unusual component to these demonstrations: the fans themselves. The protests mobilized the public present at the bleachers and were performed by fans against the government.

[3.2] If we think on the history of political activism in the Olympics, athletes have long played an important role as individual or group demonstrators. Since its early decades, competitors have used the opportunity provided by the presence of spectators to express themselves politically about specific causes. One of the first protests conducted by athletes dates from the 1906 Intercalary Olympics in Athens, an official competition that took place between the 1904 Sant Louis Olympics and the 1908 London Olympics. Irish long jumper Peter O'Connor gave the Olympic lap at the stadium carrying a green flag, referring to the colors of the republican movement that would proclaim Ireland's independence only ten years later. He had his record invalidated by the English judges (Phelan 2014).

[3.3] O'Bonsawin (2015) argues that as far as demands from interest groups and political minorities are concerned, the Olympic movement reacts slowly: "The actions of marginalized athletes who contest ongoing state violence and oppression are denounced and rejected as political and racial propaganda" (215). Analyzing the episode involving American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, famous for the symbolic gesture on the podium with closed gloved fists at the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games, and putting it side by side with the case of Australian boxer Damien Hooper, who in 2012 was prevented by the Australian Olympic Committee from fighting with a uniform bearing the aboriginal flag, the author notes that little or nothing advanced with respect to subsequent denials the expression of pride by indigenous identities and ethnic minorities in Olympic sports. The conclusion is precisely the same reached by Simon Henderson (2009), after analyzing the banning of South Africa under the Apartheid regime of the Olympics until 1992 in Barcelona.

[3.4] One can also easily discover similar responses to nation-states conflicts in previous editions of the Olympics, which makes it evident that the IOC does not work to prevent these political actions with the same rules applied to athletes or the public. Over the last five decades, the Olympic Games have experienced different boycotts and staged numerous demonstrations. From the most known cases of political retaliation during the Cold War—the refusal of 60 countries to participate in the 1980 Moscow Games and the reprisal of the Soviet bloc at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, the Black September in Munich in 1972— international conflicts have always been an intrinsic part of the Olympic sports dynamics, in fact, since their origin, tied to national identities in competition.

[3.5] As Boykoff (2011) recalls, the adoption of the term "human dignity" rather than "human rights" as the ultimate goal of a campaign to promote sports is revealing of a marked conservatism in IOC positions. Cha (2010, 2373) classifies this kind of measure a "de-politicizing effort" in the Olympic Games, recalling Beijing's efforts to "quiet" all domestic political protests by imprisoning various activists. After a torch tour disturbed by the international community, with protests led by actress and UNICEF ambassador Mia Farrow, with the participation of Steven Spielberg, Brad Pitt, and Angelina Jolie, the pressure for a boycott of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games was only reduced when the Olympic torch came to China that year. The response came in the form of generalized buycotts and a wave of nationalism among the Chinese (Hong and Zhouxiang 2012).

[3.6] In London in 2012, protests remained centered around demands for environmental and economic sustainability of Olympic equipment and the so-called Olympic legacy (Boykoff, 2017, 10–11). Something similar happened in the 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games, which also saw demands for sustainability, when "safe spaces for dissent" were set up in armed tents in the Olympic Village and an alternative media coverage with independent social media distribution emerged (Boykoff 2011, 53).

[3.7] In Brazil, there were several reports of solo demonstrators or small groups, friends and family, who appeared in stadiums as fan-activists. The actions were punctual and discreet, performed nonviolently and generally assuming a quasiludic character, involving the bearing of posters, T-shirts, and flags that denounced Dilma Rousseff's impeachment as a coup to Brazilian democracy. The performances were filmed and photographed not only by the participants themselves but also by the media, especially those belonging to an alternative media ecosystem, such as the collective Mídia Ninja. Mainstream media carefully managed to avoid the scenes. The demonstrators, on the other hand, wanted to cause discomfort to editors of live images, and consequently to reach greater public visibility. It's very common, for instance, that soccer broadcasts focus on fans partying in the bleachers, and it became a mediatized strategy for some groups to carry posters with compliments and greetings to sports speakers in order to catch their attention. These posters turned in a kind of memetic behavior of Brazilian sports fans, broadly recognized by funny expressions like "filma nóis galvão" (film us galvão)—a reference to nationwide play-by-play Globo Network announcer Galvão Bueno.

[3.8] Even before the Olympics, very similar tactics were being used by sports fans at the stadiums, especially in soccer matches. Using the typical features of organized fandoms, such as posters and flags, fan-activists demarcated the political territory of the bleachers and sought media attention through connective actions (Bennett and Segerberg 2012; Highfield 2016).

4. Sports (fans) activism

[4.1] At least one different element distinguishes the 2016 Rio Olympic Games from the previous experiences with protests in mega events, as in these Games the actor of the protest was the fan. Two other factors combined with this one were fundamental to the social mobilization atmosphere during the games: the political playing and the spectacle of mediatization, evoking fan culture.

[4.2] Protesters were ordinary spectators of the event, there to watch the games while protesting, and they protested using the usual resources and repertoires of sports fandom, like carrying flags and posters or combining uniforms, booing, and singing together cheerleading songs. Sports fans in Brazil are used to evoking these repertoires in order to support their teams and to call attention not only from the rivals but also from the media. So, they shout and sing louder, they bring giant flags to stadiums, they provoke players and also speakers themselves. In 2010, for instance, speaker Galvão Bueno was in the center of one of these jokes. During the opening ceremony of the South Africa World Cup, Bueno, who was commenting the ceremony for Globo Network, was accused of too much chattering. On Twitter, Brazilian fans started to post messages with the hashtag #calabocagalvão, which means #shutupgalvão, a Portuguese expression. Many foreigners started to ask themselves what the phrase stands for. One humorous blogger then created a prank explaining that #calabocagalvão was supposed to be a campaign for saving "Galvão birds" of extinction, and every tweet with that hashtag would donate one dollar for nongovernmental organizations concerned with the campaign. Described by Heather Horst (2011) as the world's biggest in-joke, the cyberprank was reported by the New York Times (Dwyer 2010) and is well-documented even in the Wikipedia entry for Galvão Bueno in English.

[4.3] This mode of rooting dates back to the 1940s, when informal groups of fans started to use fireworks and large flags for celebrations at the bleachers. Around the 1960s, most of these groups had already became formal organizations, known as torcidas organizadas (organized rooters). So, Fluminense Football Club has the Young Flu, Flamengo is represented with Raça Rubro-Negra ("Red and Black Race," in allusion to the club colors) and Torcida Jovem Fla ("Young Rooters Fla," in a free translation). Corinthians has the Gaviões da Fiel ("Faithful Hawks"), Palmeiras has the Mancha Verde ("Green Spot"), Cruzeiro has the Máfia Azul ("Blue Mafia"), Atlético Mineiro has the Galoucura ("Mad Roosters," which refers to the team mascot), and many others. Some of them are so much consolidated that they conduct social campaigns, get benefits from the clubs like free tickets, and had reserved places in the bleachers. A small portion even evolved to bigger and independent initiatives like samba schools, such as Gaviões da Fiel and Mancha Verde in São Paulo Carnival.

[4.4] Other organized sports fandoms like the barras bravas in Argentina, the porras in Mexico, and the ultras in Europe and Africa are also well known for similar behaviors, although the torcidas organizadas in Brazil not only use giant flags and sing all the time using musical instruments but also have humorous playing as an element of distinction. Before FIFA imposed a set of guidelines for the equipment (like security and comfort norms for the arenas), Brazilian stadiums had a popular space known as the Geral (General), where popular tickets would allow poor people to watch the matches with a direct (not superior) field view, and lots of sports fans were costumed like Superman, Bin Laden, Lula, and so on.

[4.5] All these elements were somehow appropriated in political protests performed at the bleachers by sports fans during the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. To better understand what sports fan activism means in Brazil, it's absolutely necessary to recover three distinct aspects of its ritualized practice: the self-recognition of the subjects as rooters instead of fans, their role as casual and humorous protesters, and their desire for media promotion. Below, we discuss each of these elements in detail, calling attention to how these three vectors can constitute a framework for analyzing this practice.

[4.6] Fans or rooters? The term "fan" is rarely employed in Brazil to designate the sports fan. Although the term was originally coined to refer to sports fans in the late nineteenth century (Curi 2010), the word deriving from a contraction of the Latin fanaticus—that or the one who is possessed or has been abducted by a deity or a demon; who had divine inspiration; or that belongs to a temple or a sect—there's no such use in Brazil. Instead, when it comes to sports, we usually refer to torcedores (rooters). This difference may help us realize that what we generally call political fandoms is a theoretical abstraction and does not find parallel in self-recognized discourses of sports fan-activism. Native categories like rooters thus can better express the political behavior of some social groups.

[4.7] Cultural studies (Freire Filho 2007; Jenson 1992) helped to end the pejorative connotation, interpreted as a social pathology or deviant behavior. This new understanding allows the category to draw on other fields of knowledge. Media and democracy studies, for instance, have expressed greater interest in the last years in the identification of political fandoms (Parikh 2012; Sandvoss 2013; Brough and Shrestova 2012).

[4.8] Sandvoss (2013, 264) argues that the enthusiasm about politics is similar to the way sports fans cheer for their teams. In both cases, there is an identity affiliation and a discursive competition between rival groups. One could say that rather than the identification with the party (or the team), there is a sense of belonging and an identification with the fandom itself, even ideologically (266), following the conception of homophilic audiences of Dvir-Gvirsman (2017). In addition, Sandvoss also draws attention to discourse anchored in sports metaphors in the political universe, especially the framing of electoral running, to which some authors refer as "horse-racing" or "game-frame" (264). The celebration of victory or disappointment over the failure of a candidate mirrors, to a large extent, the behavior of other fans, given the deep affective investment (265; see also Papacharissi 2014). It is the moment when the virtues or merits of candidates are exalted.

[4.9] Political fandoms articulate, therefore, performances of taste and elements of distinction in the same manner as do other fandoms. The similarities between political fans and sports fans are so remarkable that activists (or enthusiasts) should recognize themselves as fans, suggests Sandvoss (2013, 258). But this would be, somehow, another artificial theoretical construction, for the fan presupposes an idol.

[4.10] Commenting on the rapprochement between popular culture and politics, Van Zoonen (2005, 56) states that the exercise of our preferences is increasingly a fundamental component of entertainment, especially in reality shows that invite viewers to elect participants to follow in the game. It is, at the same time, a practice that mixes the elective character, the competition, and the fandoms. Political fans suffer from the common perception that politics should form citizens, whereas entertainment would only form fans. On the one hand, we would have a cognitive critique, and, on the other hand, only an affective appreciation (56).

[4.11] But the organization of cultural fandoms is, in many ways, similar to how party politics itself is organized. Recovering the typology developed by Abercrombie and Longhurst in 1998, Van Zoonen (2005, 60) argues that one can capture the mass-mediated politics in a scale of involvement degrees, in which there are: (1) the voters as fans, who are particularly attracted to a party or a candidate and have relatively casual involvement with politics; (2) campaign volunteers as "cultists," who constitute more organized networks and often meet at conventions; and (3) partisan representatives as "enthusiasts," who are guided by activities and processes, not by individuals or institutions. Similarly, we could establish comparisons with casual sports fans, organized rooters, and associate members of sport clubs.

[4.12] According to Van Zoonen (2005, 64), the fandom "is built on psychological mechanisms that are relevant to political involvement: they relate to the realm of fantasy and imagination on the one hand, and to emotional processes on the other," as mediators in the conformation of what Papacharissi (2014) describes as "affective publics." These two components are consistent with Street's (1997) perspective that politics operates through the constitution of groups and communities "around which people establish their similarities and differences (their identities), communities that exist in the memory and in the passage of time" (39).

[4.13] The metaphor of the rooter, however, makes explicit the expectation developed, imagined, or inculcated around the success of its object of admiration. While the fan is characterized as someone who follows or venerates an idol, the rooter expects to celebrate the victory over his equals; he mobilizes himself for competition, and this is why he must wield the biggest flag, he must shout louder, he must call more attention than others and support his team better.

[4.14] The game-frame is inherently connected to the sports fan-activism. Differently from other fandom practices, the element of agon, conflict (as well as the ludus, i.e., play, as we will see below), is remarkably present in sports fandoms. Though we are here concerned with casual fans, these actions performed in the stadiums are clearly driven by a clear purpose and a competitive attitude, ready to rhetorically declare victory over the target in a media battle.

[4.15] For calling attention to these distinctions, we want to highlight how political activists must be understood in a pragmatic sense not a normative one, that is, in light of ritualistic practices performed and self-recognized by their own. Sports fan activism may be better analyzed from this perspective, if we cautiously observe its particularities in relation to other fan-activist dynamics.

[4.16] If agon is one recurring element of sports fandom, ludus, play, is another intrinsic element in this universe. Sports fan-activism cannot be fully understood if we do not call attention to its ludic behavior. Even in more radical actions, like field invasions, play is evident.

[4.17] The conception of political play was introduced in literature by W. L. Bennett in 1979 in his seminal essay, which argues that "it is tempting to relegate play to the realm of games, sports and children's activities" (331), but play may occur in the context of other social and age groups and in other interaction practices such as sex play or intellectual play. The political play, he says, is one that questions the basis of authority or the use of force, which redefines or problematizes issues, which guides the public agenda or creates new rules to guide it (336). It is, in short, a device most often used as a form of political action by repressed or alienated groups, which normally lack consistent organizational structures to sustain an engaged persistent action.

[4.18] According to Bennett (1979), political play may present itself as a strike, a series of protests or actions undertaken by solidarity networks. It usually consists of a dynamic that takes shape in a playful transformation of politics. Chagas (2017) sought to establish some principles for a differentiation between the readings of politics as game and politics as play. The fundamental point of this distinction lies in the strategic approach of politics in the former, as opposed to an understanding of the political scene from drama and the performance of its actors in the latter. The constant alternation between these two perspectives, once again, can be found in the world of politics as much as in sports.

[4.1] However, in order to understand the meaning of political play, we must focus our discussion on four of its fundamental components: (1) the political aspect of the play, (2) its influence on reality, (3) its public character, and (4) the desired results. These four elements make up the framework by which play is established.

[4.20] As to the political aspect of play, we may borrow Jasper's expression on the "surreptitious resistance" of social movements to call attention to play as the "weapon of the weak" that is "used with the public in mind" (2014, 37). Read as staged performance, play does not necessarily constitute a social movement, especially if we take into account the casual involvement of its actors. Even so, the play uses typical routines of protests undertaken by social movements when searching for windows of opportunity. As Bennett recalls, however, both sides need to agree on performance, since the play involves risks, including the integrity of the actors (1979, 336).

[4.21] As to its influence on reality, Bennett (1979, 335) asserts that political play, like other forms of play, can be seen as fantasy (performed by a single actor) or behavior (inscribed in a social form). It may also emerge from a recreational context of leisure or as an eminently serious activity. It is very common to attribute to play a marginal character in relation to the political protest in its strict sense. This is due in large extent to a mechanism of co-optation introduced by the institutionalization of politics in relation to conflict, as described by Miguel (2015, 39–40). In this sense, political play is more often than not a threshold experience of provocation, which is intended to test the frontiers of obedience, and is the last and most ingenious step before violent action. This brings us to the question posed by Street (1997, 27) about the conversion of popular culture into a political subject. As he argues, in a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, it is precisely when one urges the control of political expression that it is itself politicized.

[4.22] As to its public character, political play requires socially planned efforts, even when it encompasses the merely casual involvement of its actors. It also operates in situational contexts, not sustaining for long if not as repeated tactical intervention. In political play, the actors' involvement is unstable, uncertain, discrepant, and casual. In addition, this involvement may fluctuate on a scale from mere association to a collective agenda (like in click-activism) to a private manifestation of nonconformity and grievance, as in the case of buycotts in fan-activism (Brough and Shresthova 2012). The actors' involvement ultimately ends in resuming the effects of the action, since, as Bennett (1979) warned, to be read as a political behavior resulting in direct action on reality, play needs to garner players.

[4.23] And, finally, as to the desired results, play is tactical, directed to politicize an issue. Thus, in politics, as in sports, play is performed for an audience, one that gives it meaning. This implies that in most cases—such as booing politicians at stadiums or wearing costumes and carrying posters with funny messages expecting to be filmed—actions are not only socially mediated but also mediatized.

[4.24] The final vertex of this framework relates to media participation. The political actions of sports fans generally aim to attract media attention and foster visibility for their claims. The concept of mediatization was introduced as a theoretical hypothesis in the 1980s by Kent Asp and was subsequently developed by the Nordic school which incorporated this research agenda (Hjarvard 2013; Strömbäck 2008; Strömbäck and Esser 2014; Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999). It proposes a conciliatory approach between theories of media effects and reception studies (Hjarvard 2013, 16–20).

[4.25] According to Strömbäck (2008, 229), politics has become mediated and mediatized. But the processes of mediation and mediatization are not equivalent. With strong inspiration from the perspective of framing effects, mediation theory presents media as the most important source of information and the main channel between representatives and represented (231; Bennett and Entman 2001). In this way, both public and elites create a dependence relationship with media, either to keep informed or to reach people.

[4.26] Unlike mediation, mediatization presupposes the incorporation of media logic into performed social activities (Strömbäck 2008; Hjarvard 2013). The logic of the media operates as "a frame of reference from which the media constructs the meaning of the events and personalities it reports" (Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999, 247; see also Blumler 2015). Thus, the spectacularization of politics is one of its main effects, since the internalization of this logic contributes to broadening the power of the media to shape society, exerting control over both public opinion and political behavior (Hjavard 2008; Strömbäck 2011).

[4.27] In short, mediation is a first stage of mediatization, according to Strömbäck and Esser (2014). Mediatization can also serve to stimulate political action since internalization of media logic also generates social expectations before political demonstrations. Donges and Jarren (2014) show how nonformal political actors have been appropriating these routines, staging for cameras in mediatized political plays, such as the ones performed in sports venues. That's what Strömback (2011) defines as a "spiral of mediatization," an action that seeks an opportunity window to spawn similar ones.

[4.28] In the next section, we try to evidence all of these three aspects discussed above, using brief case studies that took place in the 2016 Rio Olympic Games.

5. Rio 2016 protests: Serious matters cannot taint the show

[5.1] In February 2018, Brazilian sports journalist Thiago Leifert—who happens to be also the current host of the reality show Big Brother Brasil—wrote a piece where he asks if "a soccer match [is] the right place for political demonstrations" and he himself answers "I don't think so." Concerned with the electoral year in Brazil, he said that the mixture of sports and politics is not a good one, and recalls the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Rio Olympic Games demonstrations. Saying that he doesn't appreciate that players "hack" an event such as a soccer match, he says "There's a lot of contaminated stuff out there. We need to immunize the little space we still have for fun" (2018). Leifert is by no means alone in his crusade.

[5.2] In June 2013, Brazil watched mass street demonstrations. Protests coincided with the FIFA Confederations Cup, considered a dress rehearsal for the World Cup, and were marked by severe police clashes outside the stadiums even during the final match. Then-FIFA president Joseph Blatter even called on protesters "to stop linking demonstrations to football" (Watts 2013; Withnall 2013). Despite Leifert's aspiration, the 2018 World Cup in Russia also saw political demonstrations when Pussy Riot punk members broke onto the field during the final match between France and Croatia in a much more radical protest against Putin's government. Broadcast television also emphasized Iranian women rooting for their team, remembering that in Iran they are not allowed to go to the stadiums. Some of them would also reprise Brazilian fans with posters with sayings like "Support Iranian Women to attend stadiums" (Villar 2018).

[5.3] Turning to the relationship between Olympism and politics, the IOC representatives, in their speeches and official documents, point out that these are isolated incidents and that the Olympic Games, understood as a moment of celebration between peoples, cannot be profaned by political disputes. This perspective is reinforced in the Olympic Charter (IOC 2016), a document that proposes to establish the general guidelines of the Games. In its second paragraph of Rule 50, the IOC states that no political manifestations or propaganda can be carried out in the equipment and spaces designated for competitions.

[5.4] But some contradictions are noted in a recent study by Drumond (2017), which calls attention to the incoherence present in the IOC's position in asserting itself as an apolitical entity. The researcher points out that the Olympic Games (and also the process of choosing host cities) dialogue directly with national representatives. In addition, we understand that, during the competitions, countries affirm their symbolic (or soft) power in the world.

[5.5] Beyond that, we must bear in mind that the IOC has more affiliated countries than the UN itself. Citing the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, Drumond (2017, 6) states that at the opening ceremony, 207 national delegations marveled at Maracanã and, "Among these delegations, in addition to the new Olympic Refugee Team, 13 National Committees represented countries or territories with limited or dependent recognition, without international recognition." These data highlight the IOC's position in global geopolitics. The treatise, provided to the athletes and fans, however, moves in the opposite direction, with their individual manifestations restricted by the aseptic discourse in relation to politics, assumed in this case as the very origin of the contamination of the Olympic ideal.

[5.6] In the Olympic Charter (IOC 2016), the International Olympic Committee textually affirms that "No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic venues or other areas." On the other hand, the fundamental principles of Olympism contained in the same document make explicit reference to respect and nondiscrimination of any kind, such as race, color, sex, sexual orientation, language, religion, political opinion, or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, or any other status."

[5.7] The contradiction is also present in Brazilian Federal Law No. 13.284, promulgated on May 10, 2016, as one of the last acts of President Dilma Rousseff when she was still in office (she was removed from office on May 12, after the Senate voted to open the impeachment process against her). Article 28 of the above mentioned law establishes as a condition for the permanence in the official venues of the Games "not to bear or display signs, banners, symbols or other signs with offensive messages, of a racist or xenophobic nature or that encourage other forms of discrimination" (item IV) "not to use discriminatory, racist or xenophobic slogans" (V), and "not to use flags for purposes other than festive and friendly manifestations" (X), but at the same time states that it ensures "the constitutional right to freedom of expression and full freedom of opinion in defense of the dignity of the human person" (X).

[5.8] Both documents, the Olympic Charter and Brazilian Federal Law, were subject to intense discussion, especially during the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro in August 2016, when demonstrators were banned from stadiums. Beyond that, the Federal Constitution of 1988 was also the subject of intense disputes over the limits of its actions regarding the defense of the rights of expression and political manifestation in the country.

[5.9] Between May 2016 and August 2016, Brazil faced its second impeachment process in less than 30 years. This time, an action fostered by an opposition party unsatisfied with the electoral result in 2014 together with other parties started a process with controversial accusations against president Dilma Rousseff. Ending with her definitive removal from office on August 31, the whole judgement was described by many as a parliamentary coup. Michel Temer, Rousseff's vice-president, inherited the presidency up to December 31, 2018. At the time of the 2016 Rio Games, Temer was the acting president of Brazil, with an approval rate of only 1 to 3 percent. He was then the main target of political protests at the stadiums, bringing together the ones opposed to impeachment and the ones simply opposed to all politicians.

[5.10] On August 3, one Olympic torch runner was arrested by police after lowering his pants and shouting "Fora Temer." During the opening ceremony, Temer was massively booed, but broadcast television managed to hide the public demonstration in an attempt to remedy (or remediate) the circumstances. Many internet memes emerged with humorous footage showing fictional protests. In several live transmissions, people interrupted the journalists or simply raised posters with protest messages. On the first three days of competitions (August 6 to 8), lots of other creative demonstrations took place (figures 3 to 6), invariably ending with National Security Forces agents approaching and banning the individuals. On August 8, federal judge João Augusto Carneiro Araújo, in response to a Public Prosecutor demand, granted an injunction allowing this kind of demonstration. A huge debate on Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter was held before the Brazilian Constitutional rights of expression.

Figure 3. Another sports fan protesting during the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. One can read on her arms the phrase "Out Temer." Source: PT Minas Gerais. Photograph taken by PT-MG, 2016.

Figure 4. One more sports fan holding a poster with the phrase "#OutTemer." She is wearing a Vasco da Gama team uniform. Source: O Globo. Photograph taken by Leo Correa / AP, 2016.

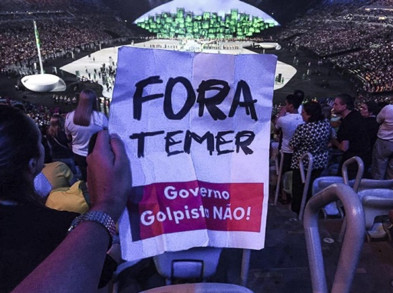

Figure 5. One sports fan taking a picture of himself at the stadium with a poster on which one can read "Out Temer / Coup Government: NO!" Source: Mãdia Ninja. Photograph reproduced from Facebook, 2016.

Figure 6. A large banner at the stadium on which one can read "Stop the coup in Brazil / Out Temer / Roses for Democracy." The last expression is the name of a women’s left-wing collective linked to the Worker’s Party. Source: Independente—Jornalismo Alternativo. Photograph reproduced from Facebook, 2016.

[5.11] In a sample of this debate, a BBC story interviewed jurists Oscar Vilhena and Ronaldo Porto Macedo, each one assuming a distinct position (Fagundez 2016). The former argued that exaggerated precaution could lead to disproportionate restriction, while the latter stated that some civil rights such as going to the venues with rainbow clothes must be preserved, but everything strange to the spectacle should be restrained. Araújo's decision was confirmed the next day, when the government appeal was dismissed, and the Union and IOC had to deal with the demonstrations without banning the sports fans from the competition venues. Until the end of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, Brazilian fans could go to the venues wearing T-shirts and holding posters against Temer and the impeachment. Though broadcast television managed to avoid most of these images, alternative media captured the playing atmosphere in photographs and videos, showing that sports fans do root for their teams as much as for democracy.

[5.12] The mediatized and opportunistic intention that drives activists transpires when sports fans go to the arena looking to perform to the cameras, wearing protest T-shirts or holding banners with political messages but still behaving as ordinary rooters. This cynical and at the same time antagonistic conduct reinforces the humorous nature of the performance. There is no idol for this fandom but a cause to inspire. If put together, these three components (the activist-rooter, the political play, and the mediatization of the action) can help us understand how the demonstrations created and occupied gaps in the law, fostering a serious discussion on freedom of expression. Contrary to Leifert's opinion, these fans were having fun politicizing a sports event.

Figure 7. At a competition venue, a sports fan, wearing a Flamengo team shirt, is banned from the bleachers by National Security Guards, after shouting "Out Temer." Source: Estãdo. Photograph taken by Diego Azubel/EFE, 2016.

Figure 8. Two sports fans are interviewed live by a reporter from Globo Network while another one in the background holds a poster where one can read "Fooooora Temer" ("Out Temer"). The Olympic Rings are placed instead of the "o." Source: Mídia Livre. Image captured from YouTube video, 2016.

Figure 9. An Argentinean athlete parades live during the closing ceremony and shows her hand palm facing out where one can read "Fuera Temer" ("Out Temer," in Spanish). Source: UOL. Photomontage produced by an unknown author, 2016.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] While cultural studies scholars have been attentive to fan activism, and most recently political theory scholars have considered political fandoms an important field, there is still little debate on sports fans' political demonstrations. This paper calls attention to this phenomenon from an approach based on three vectors: sports fan activism, political playing, and incorporated media logic. Episodes such as the "Fora Temer" mosaic on T-shirts prove that some repertoires of fan cultures common to sports fans are also used by fan-activists to make political claims. We suggest that the category of fan must also be further discussed when applied to sports and political fandoms, considering the disputes and competition background for which they are not only fans but also rooters.

[6.2] This same case allows one to question the neutral policy of IOC and other sports entities, which persist in claiming that sports and politics are separate from each other. While there's nothing new to this specific debate, we consider that the staged protests at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games present an important contribution to it.

[6.3] This paper also proposes a first approach in order to understand political play as a form of disruptive and mediatized action. We expect to further develop other theoretical questions that surround this debate.

7. Acknowledgments

[7.1] The authors would like to thank Kelly Prudencio and Fernando Lattman-Weltman for the attentive reading and commenting on early versions of this paper. We also thank the editors of this special issue and the anonymous reviewers for the insightful remarks from which this article has benefited.