1. Private eyes

[1.1] Let me introduce you to Olivia Benson, a dedicated yet personally tormented detective who investigates sex crimes in New York City and sports a deadly weapon, a leather jacket, and a short haircut. She's hopelessly in love with assistant district attorney Alexandra Cabot, who prosecutes her cases—they're each other's domestic partners, occasional lovers, or secret crushes, depending on who is telling the story. That is, these individuals are fictional characters on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (SVU; 1990–present), and the question of whether Olivia could be Alex's (or anyone's) girlfriend is a particularly contested one across online SVU fandom: some fans are determined to claim her as gay, while others insist that she's straight. Although there is clearly intense investment on both sides in definitively verifying the answer, there is at the same time much confusion about the proper source of the necessary evidence: text, subtext, or metatext. In this essay, I chronicle the inquests of three detectives with parallel mandates to uncover the truths of desire: the TV character, who is hot on the trail of New York City's sex offenders; the SVU fan, who watches the show vigilantly for clues to who is in Olivia's heart and in her bed; and the television scholar, who is fascinated by these epistemological conundrums, driven to investigate how we might know things about television, about audiences, and about sexuality. I maintain that the projects of these three detectives are intertwined in multivalent networks that link knowledge, desire, and spectatorship across diverse registers. Within this intertextual architecture, the question of whether Olivia is "really" a lesbian is inextricable from broader ambiguities that infuse the conflicted relations between texts and audiences, academics and fans, gender and consumption, hermeneutics and erotics.

[1.2] My own romance with Olivia Benson (figure 1), played by Mariska Hargitay, began with a chance conversation at my local coffee shop that catalyzed an addiction to USA Network's nightly SVU reruns (the show's first run appears on NBC). Because of my preexisting fluency in subtextual viewing protocols, the availability of the Olivia/Alex dyad transformed SVU, for me, into a compelling nexus of speculation, imagination, and desire. Olivia and Alex are indeed a power couple of female slash fandom, one among a scattered pantheon of classic one true pairings—OTPs that certain media seem to invite us to recognize by portraying a profound, if not explicitly romantic, relationship between two characters (an archetype that, in the world of femslash, does not much predate Xena: Warrior Princess, 1995–2001). My personal engagement with their saga depends on the contingencies that shape television viewership—daily routines, a fortuitous meeting, and the topographies of social networks and lesbian subcultures (both online and off)—demonstrating how interpretations of, and libidinal encounters with, SVU the program are entangled with Internet fandom and with everyday life. Television criticism often leans toward one or the other side of the border separating diegetic content from audience reception, examining one territory in relative isolation. Here, I attempt to plot the intersections between screen text and fan text, taking them as mutually constitutive. This process incorporates the disintegration of a number of linked binaries because the indeterminacy of inside/outside or gay/straight impinges on the stability of private/public, fiction/reality, fan/critic, leisure/work, and other oppositions. Crucial among them is the rapidly dissolving frontier between television and the Internet, which brings the interdependence of TV producers and consumers ever more out into the open.

Figure 1. Olivia Benson (NBC promotional image).

[1.3] The subtext of my argument is the notion that television is itself in the closet about its digital tendencies, largely as a defense mechanism for preserving broadcast's profit models and margins. Like the question so often posed about Olivia—"is she or isn't she?"—the question "is it or isn't it TV?" has high stakes in hierarchical economies of power, and is addressed with a parallel coyness. Moreover, these taxonomic teases are interlaced and analogous: as slash fandom becomes increasingly visible and pervasive under conditions of increasingly competitive and diffuse distribution and attention, its cultivation (or at least negotiation) takes on increasing importance. Convergence, in other words, is queer, in both content and form. In this milieu, my analysis consists not of cracking the case of Olivia Benson where the aforementioned detectives remain stymied, but rather of mapping the specifically televisual limits that circumscribe their inquiries, especially at the hazardous junctions of epistemological endeavors, erotic investments, and capitalist economics. I can offer no incontrovertible proof that Olivia is a lesbian, no stable hierarchy of meaning among text, subtext, and metatext. Any evidence that might be offered is always already ensnared in the vortex of the closet, wherein the secret truths of (homo)sexuality are simultaneously exposed and effaced in relentless fluctuations between binary poles.

[1.4] What I present here is the more nuanced claim that Olivia is the fulcrum of an apparatus of lesbian desire that operates at the volatile interchanges permeating these geographies, including those that constitute television as a mass medium. Given television's interpenetration with its social context, with online paratexts, with the competencies and orientations of its viewers, the desires and procedures of my three detectives (the character, the fan, and the critic) mirror and structure each other in their pursuit of a verdict. My intervention here, while not minimizing the value of these stabilizing projects, is to delve into the unstable circuits of mutual interdependence between the strata of this textual network. I take seriously the question of how what appears on television can channel fans' deductive and creative activities, as well as the question of how fans' meaning-making can influence the import of television programs. I maintain that it is ultimately in such complex relations that the most fruitful prospects for knowledge, passion, and profit lie.

2. Closet case

[2.1] If Olivia is gay, then she's a closet case.

—Sally Forth, "An Olivia Benson Rave" (2006)

[2.2] Fans' inquests into Olivia's sexuality are animated by a politics of representation that calls for "gay characters" to come out of the closet. While I wouldn't want to belittle calls for increased visibility, it's important to remember that lesbians never transparently and unambiguously appear, and this is even more true of their portrayal on television. This rich indeterminacy is at the heart of Eve Sedgwick's intervention in Epistemology of the Closet, which investigates how, around the turn of the 20th century, the homosexual/heterosexual binary was transformed into the privileged, obligatory taxonomy for classifying all persons and all permutations of sexuality. The closet is Sedgwick's figure for this profoundly contradictory organizing principle, not only of sexual identity but also of all oscillations of secrecy and disclosure that are primordially filtered through the "one particular sexuality that was distinctively constituted as secrecy" (1990:73). This aporetic logic is all the more insistent when operating within the already highly compromised and overdetermined domain of TV representation. Epistemology and consumption are fundamentally intertwined with sexuality in the televisual economy, as Lynne Joyrich argues: "U.S. television both impedes and constructs, exposes and buries, a particular knowledge of sexuality" (2001:440) to the point that "the closet becomes an implicit TV form" (450). Joyrich observes that the media have managed homosexual desire through deliberate ambiguity, with contradictory consequences. This subtextual strategy, wherein coded desire is readable only to viewers properly qualified to decrypt it, is typically condemned (by all but slash fans) as coy, mercenary, and apolitical at best. The appearance of explicit gay characters on TV programs can serve to localize and thus contain what are otherwise more pervasive and destabilizing homoerotic undercurrents, implying that, enmeshed as we are in the inexorable seesaw of binaries, subtext or connotation is in some ways the more progressive mode.

[2.3] According to Joyrich, this strategy is a key permutation of "the [TV] industry's attempts to define sexuality as product while retaining its simultaneous anxiety around sexuality as practice" (2001:451), an economic bargain often facilitated by "encourag[ing] an epistemology (and erotics) of 'knowing viewers'" (453) (or, in my terms, trained detectives). She links "the logic of the commodity" to "the logic of the closet" (462), just as Amelie Hastie similarly calls attention to the "inherent overlap between consumerist and epistemological economies present both in television itself and in television criticism" (2007:91). One form these hybrid economies take is show tie-ins, be they commercial merchandise or fan productions. They capitalize on the viewership's coupling of desire and pleasure with the project of investigation to promote a realm of supplementary texts that drive and are driven by TV as a consumerist medium. The practices of screen, fan, and academic detectives are congruent and interdependent, shaped by interlocking modes of engagement: epistemology and consumption. Each is enabled and constrained by closet formations wherein binary terms continually reassert their authority in spite of their manifest instability and contradictions. Both academics and fans have sought out the "queer character" as an object of knowledge through the same self-perpetuating ciphers that seem to propel her ever further from reach.

[2.4] My study is necessarily engaged with a broader ongoing debate in the discipline of television studies about how to theorize the interfaces between text, audience, and sociopolitical context. These have lately been transformed from more or less stable and opposable categories to a more postmodern assemblage. We must grapple with the precarious question of whether meaning is located inside or outside the text, in representation or interpretation. Even as the programmatic binary is extensively rejected in favor of more complex, interactive models, as I show here, it seems impossible to dispense with these terms completely (note 1). We can take from this assemblage an appreciation of the interdependence of queer interpretive work and specific codes and conventions of screen representation. The quandaries of textuality and sexuality continue to merge in the present-day turn to media convergence, wherein subtext and slash as a platform for fan engagement become increasingly foregrounded in overlapping academic and industrial discussions (Jenkins 2006). By all accounts, then, we arrive at an epistemological diagram of sexuality where inside and outside interpenetrate, the television text compromised by intertextual relations and infiltrated by audience readings. This is not to suggest that no distinctions or hierarchies can be recognized across these registers. Episodes of SVU are obviously distinguishable from fan fiction stories, for example, as SVU's producers are from fans as producers, and each is differently interfaced with apparatuses of power. The point is that discourses of sexual knowledge—on the part of fans, who refer alternately to episodes, fan works, actors, and industry in attempts to find evidentiary purchase, as much as on the part of academics—make it apparent that crucial televisual boundaries stubbornly elude efforts to render them fixed and impermeable.

3. Special victims

[3.1] After the first time [Alex] wondered whether people could tell. She had gay friends who would play "lesbian/straight?" over coffee as if there were secret signs, visible only to women in the know. And maybe there was something in that. She wondered if she exhibited such signs…

[3.2] When Olivia is near she feels the whole world watching…"We should be more careful," she says, watching the squad room for signs of interest. "We shouldn't…not where everyone can see us"…sometimes she wonders if they know already. There's not much that escapes a detective in sex crimes.

—CGB, "Objects in the Mirror" (fanfic, 2004)

[3.3] Just as closet formations often intersect with work via the economic underpinnings of public and private spheres, gendered ideologies of work often collide with our perception of sexuality. Working women on screen have been an object of interest for queer and female fans, perhaps since the early days of Mary Tyler Moore's workplace family and Cagney and Lacey's police partnership. In her analysis of feminist sitcoms across several decades (here, Murphy Brown in the 1990s), Lauren Rabinovitz includes a discussion of how Murphy Brown's "assertiveness, independence, brassiness, and 'smart mouth,' as well as her tailored and even sometimes androgynous wardrobe, may suggest her capacity as a lesbian or figure for lesbian identification while references to her active, ongoing heterosexual life and desire undercut such signifiers" (1999:160). The ambivalence of connotation is in full force here, and I'd like to point out that 10 years later, lesbian-oriented fans describe Olivia, and the oscillation between the eruption and erasure of queer desire surrounding her on SVU, in strikingly similar terms. As Angie B (2004) observes, Olivia has had brushes with past or potential boyfriends on screen, but these fleeting references to heterosexuality seem far outweighed by the pervasive fact that she is

[3.4] one of the few characters on TV to exhibit what are often considered to be dyke characteristics—with short hair, a leather jacket, and a gun at her hip, Olivia sits with legs apart, commanding the space around her. She is the protector of the victims who come through her department, a strong woman in a profession filled with men, and often physically or verbally dominates "perps." Her uniform includes t-shirts, sweaters, slacks and sensible shoes—no heels, no frills, and little jewelry except for what appears to be a man's watch.

[3.5] Notably, these qualities, like Murphy Brown's, have, in and of themselves, nothing to do with sex between women. What they do imply is these characters' contravention of the bounds of properly feminine aesthetics and activities, the challenge to stable taxonomies of gender that inheres in their role as successful professionals. Though they may appear superficial and stereotypical, such historically contoured markers for encoding transgression in style and accessories are a crucial dimension of lesbian viewing strategies.

[3.6] Alongside Olivia's place in a genealogy of television's working women, it is significant that her character is located within a distinct textual milieu: the crime procedural—a form that John Fiske describes as "the primary masculine television genre," and one of TV's favored workplaces. Because, as Fiske puts it, "'most masculine texts' eliminate 'the most significant cultural producers of the masculine identity—women, work, and marriage'" (Fiske in Cuklanz 1999:18–19), it follows that the portrayal of women and private, "feminine" concerns like romance is especially conflicted here. Lisa M. Cuklanz identifies an economically motivated shift in the textual orientation of detective shows: "In the 1980s the genre became more and more similar to the soap opera, with the aim of attracting a broad-based, mixed-gender audience…the form and content of crime dramas became increasingly feminized" (24)—but such hybridization may exacerbate rather than alleviate the tensions plaguing this televisual version of separate spheres. As Louisa Stein (2008) theorizes, genre mixing is a ubiquitous media strategy, and it offers frustrations as well as opportunities to both producers and fans. In the case of SVU, the uneasy amalgamation of Olivia as police heroine and Olivia as romantic heroine, of public justice and intimate sex crimes, invites deviant desire to erupt in the interstices of deviant genre. In its orthodox capacity as a procedural, SVU trains viewers in detective work, provoking them to turn these hermeneutic pleasures back against the clues the show itself generates to its own perverse secrets. SVU's closet logics stimulate interpretive modalities that structure the interface between text and audience as a site of perpetual outing, thwarting easy distinctions between visible and hidden, true and fictional, outside and inside sexual knowledges.

[3.7] With the procedural as the milieu, the epistemological and sexual violence of such gendered, genre-d interchanges comes to the fore. Cuklanz (1999:23) provides the interesting statistic that, several high-profile sitcom episodes aside, crime shows accounted for approximately 87% of rape-themed narratives on prime time TV between 1976 and 1990 (about 87 of 100 total—that's if you include L.A. Law's 9). Joyrich also suggests (less empirically) that there may be a privileged affinity between detective programs and deviant erotics. She argues that a common mode of representing homosexuality on television is by "a logic of detection and discovery—in which hints of sexuality are offered as clues to be traced," which is particularly evident in "the hermeneutic of suspicion found in several cop/detective shows that…incites a desire to solve its enigmas, be these criminal or sexual—or frequently…a conflation of both" (2001:452–53). These unavoidable homoerotic reverberations of the sex detective's epistemological project and television's commercial project, across the various levels of an intertextual orbit, illuminate the persistent equivalence of queer and criminal sexuality in mass media representations. With its defining focus on sexually based offenses, SVU is an exemplar of these foundational incitements linking genre, knowledge, desire, and violence.

[3.8] Moreover, by relentlessly thematizing the investigation of desire through watching for signs, searching for clues, interrogating recalcitrant suspects, and fabricating plausible stories to fit the evidence, SVU is training its viewers to do the same. SVU symptomatically interweaves the quest for truth and justice with the search for the elusive frontier where normal sexuality and relationships cross into deviance, perversion, and violence, where private acts and desires cross into the public discourse of crime and the televisual spectacularization and commodification of sex. Additionally, SVU actively invites its viewers to scrutinize these contradictory fields of overlap for the illicit specters that haunt them—its marketability depends, after all, on the pleasure of learning the ways of sex detectives. Given a series whose premise is discovering clandestine sexual transgressions, how can we not be ever vigilant, as an audience, for even the subtlest signs and clues? This exercise expands as fans convene their own detective squads, collectively reviewing the facts and producing explanatory narratives in their own gratifying inquests.

Video 1. Alex, who is going into the witness protection program, says an emotional good-bye to Olivia (5.04 "Loss").

[3.9] The interpretive networks of fans who see Olivia in an erotic relationship with Alex (or other female characters) synthesize and rework SVU's on-screen languages to articulate the results of their libidinal investigations. Shaping this process is a critical awareness, first of all, of the televisual constraints circumscribing the portrayal of sexuality. Angie B (2004) reiterates the widespread recognition that the generic conditions of this detective series dictate that "the show deliberately does not focus on the personal lives of its characters." This attribute incites and justifies disproportionately intensive deductive formulas: in the rubric of one group (Baby Lurches, now off-line), for example, one drink between characters in the diegetic realm equates to a sexual liaison, once you control for the program's acute representational restraint. Moreover, I'd contend that many fans are also consciously engaged with the ways the more enfolding contortions of the closet manipulate the visibility of lesbian eroticism, both on screen and off.

[3.10] As I (along with commentators like Sally Forth and Angie B) have theorized SVU, the elements that conspire to render Olivia unrepresentable as a lesbian on screen are ultimately extratextual: our culture's pervasive homophobia; the economic imperative to appeal to a mass audience; the gendered hazards bequeathed to television by historical hierarchies and transformations; the insidious ubiquity of the closet. Fan fiction stories, however, often transpose the impediments to Olivia and Alex's romance from outside the text to inside the characters' psyches, reconstituting these oppressions as their individual fears and inhibitions. Even when fics thematize, as they often do, Olivia's or Alex's struggle with prejudice or internalized homophobia, these conditions are still located as hang-ups that, although perhaps seething with acknowledged violence, can be processed and (usually) overcome privately. Simultaneously, stories may transpose the fans' procedures of watching (obsessive scrutiny of the characters' attire, vigilance for suspect looks and touches), as well as their tendency to fantasize about what they see, into the heads of the characters, converting the viewers' competencies as sex detectives into Olivia and Alex's erotic waltz. What appears is a kind of machine for collapsing TV's divergent registers into each other, a libidinous interface with the perpetual flows of meaning wherein SVU episodes, industry gossip, and fan production penetrate and transform each other. It is in this interactive destabilization of the ostensibly obvious perimeters distinguishing text, audience, and metatext that lesbian desire in the televisual sense operates.

4. Is she or isn't she?

[4.1] Mariska: A week ago, I'm walking down Seventh Ave. […] and all of a sudden this guy yells, […] "Damn! I thought you were a lesbian!"

[4.2] Conan: Really? Because of your character [Olivia Benson] on the show?

[4.3] Mariska: Yes, everyone thinks that, and I don't know why.

—Mariska Hargitay on Late Night with Conan O'Brien (April 2003)

[4.4] All SVU slash to some degree engages the circulation of sexuality across variable strata. Crucial to such circulation is plausibility: how much responsibility do fan writers have to textual fidelity? How much leeway do they have to transform the primary text from without? This dispute is rendered in fan jargon as canon versus fanon. Henry Jenkins notes that rejection of slash fan fiction has "less to do with the stated reason that it violates established characterization than with unstated beliefs about the nature of human sexuality that determine what types of character conduct can be viewed as plausible" (1994:468), although Sara Gwenllian Jones critiques this tendency, pointing out that "in such formulations, slash is interpreted as 'resistant' or 'subversive' because it seems deliberately to ignore or overrule clear textual messages indicating characters' heterosexuality" (2002:81). A verdict in Olivia's case could only be provisionally negotiated among three epistemologically incommensurate but inseparable layers: screen texts, fan texts, and the social context that mediates among them. These layers are negotiated differently by different viewers: "heteroglossic cultural references which are easily read one way by queer viewers" are read "quite differently by heterosexuals unfamiliar with the queer lexicon" (Jones 2000:19), yet the "deficit between what is presented on screen and what is implied or omitted that cult television formats exploit in order to enthrall viewers" (13). In other words, the diverse pleasures fans glean from imaginatively filling in what their favorite shows formally and strategically leave out is a crucial element of marketability. In this sense, Olivia's chronically boyfriend- and girlfriend-less condition is an impetus of SVU's popularity because it stimulates much of the speculation and argument that swirl around her.

[4.5] Discourses arguing the case of Olivia Benson promiscuously intersect the structuring oppositions of sexuality and television alike. At issue is what register of evidence for Olivia and her ilk's orientation is ultimately definitive: the television text, or the extratextual milieu. The former offers proof in the form of mysteriously cathected scenes with Alexandra Cabot, short hair, and butch accessories; the legitimacy of audience interpretations, viewing practices, and communities that resoundingly proclaim Olivia's lesbian desirability. The latter assesses the conscious intentions of the show's producers for the character and the economic necessity of keeping her palatable to a broad audience, the (perhaps excessively) open heterosexuality of Mariska Hargitay, homophobia, and the dearth of "real" lesbians in the mass media. Such boundary confusions are figured in fiction, but they are more than just a metaphor. The unreliability of its own perimeter was a founding condition of television: because "experts of the period [the 1950s] agreed that the modern home should blur distinctions between inside and outside spaces," as Lynne Spigel notes, "television was the ideal companion for these suburban homes" (1997:212–13). At the same time, this ambiguity was the source of acute "anxieties" as "popular media expressed uncertainty about the distinction between real and electrical space" (219). Television's tendency to perforate and compromise the frontiers between discrete spaces, generating contradictory overlaps and simultaneities, only intensifies with media convergence. Resolution to the enigma of where diegetic authority stops and audience interpretation begins is frustrated by design as paratexts—including online promotions, interactive network Web sites, and fan sites—further erode the circumference of the medium. Such transmedia branding leads to what Sharon Marie Ross calls teleparticipation, or "invitations to interact with TV shows beyond the moment of viewing and 'outside' of the TV show itself" (2008:4).

[4.6] Thus, the mystery, "is she or isn't she?", is inextricable from the mystery of what television itself is: if we can't determine the boundaries of television, then evidence for our mystery will never be stable, rendering convergence a closet brimming with speculation and creativity. Just as television technology—the signal's perpetual transmission through the walls of the home, the scanning beam or pixels that only simulate a fixed image—is central to the difficulty of confirming its limits, the Internet platforms of television fandom are integral its border wars. In her "Brief History of Media Fandom," Francesca Coppa observes that from the 1990s, "the movement of fandom online, as well as an increasingly customizable experience, moved slash fandom out into the mainstream" (2006:54), making it more influential in both the production and consumption of mass media. In an initial shift from fan activity on Usenet, "mailing lists customized fandom by allowing fans to select from among their fannish interests, [then] blogs such as LiveJournal.com…began to be widely adopted across fandom around 2003, where it caused a wide-scale reorganization of fandom infrastructure" (57). SVU spanned this transition, which is a factor in the varied geography of its slash following: a compendium of links to author pages, Yahoo! mailing lists, LiveJournal communities (figures 2 and 3), multimedia archives, and official Web sites (http://xenawp.org/svu) offers some sense of the broad scope of slash activity around Olivia, who is paired with Alex as well as other female SVU characters.

Figure 2. Community header image by p_inkjeans for the LiveJournal community ob_fangrrl. [View larger image.]

Figure 3. Community header image by aleatory_6 for the LiveJournal community alex_liv_lovers. [View larger image.]

[4.7] Online fandom's technological substrate makes particular registers possible in the open case file on Olivia Benson's sexuality. Although SVU fans of various orientations display an intense investment in definitively determining the truth, there is significant confusion about where to locate legitimate evidence. The hermeneutic uncertainties of fan discourse parallel those that vex scholarly discourse (to the extent that these domains are distinct), revolving around the axes of television's inside and outside, knowledges private and public, and media producers and consumers. Given the indeterminacy of the borders of both heterosexuality and textuality, there is little hope of closing the case once and for all, but the inquests and debates can illuminate the prolific operations of the closet. While social networking interfaces tend to gather like-minded fans to discuss a loose cloud of topics, more linear message boards may invite fans from diverse subcommunities to discuss a clearly defined topic, and as such, they are a platform where such debates almost inevitably erupt.

[4.8] One notable thread, on the officially sponsored yet largely unmoderated SVU board at USA Network's Web site (the program airs on the USA Network in syndication), can serve as an example of the vehemence and complexity of the testimonies mobilized in attempts to prove that Olivia is gay or straight (note 2). It begins with a cautious, open-ended query by mariskafans: "So, would anyone be too terribly offended if Olivia started dating a girl?" Tellingly, the question is immediately transmuted into a dispute over Olivia's probable sexual orientation. Some fans consider only the most explicit textual citations admissible as evidence, and say so quite emphatically:

[4.9] dtobe2008: She is DEFINITELY straight. There have been many episodes where she's had a date with a man and you've seen a few.

[4.10] teresa985: The fact that she's dated men before on the show, and no women, leads me to believe that she's straight. Unless she flat out says: "I'm dating a woman" or something of that nature, I'm not going to believe she's a lesbian.

[4.11] Others respond to this literalism by pointing out the inherently partial picture of Olivia's desires that the screen text offers, alongside the possibility of a less rigidly binary sexuality:

[4.12] Bekster: We don't know that she's straight—she's mentioned a significant other, what, once? She could definitely be bisexual, which would be great, she's gorgeous!

[4.13] Kloie: And…just because a girl's slept with men doesn't necessarily mean she's straight. lol

[4.14] This tactic is then countered with references to extratextual gossip (the avowed heterosexuality of Hargitay) and TV industry logics (the imperative to appeal to a mass audience and remain within the program's formal constraints):

[4.15] svu junkie: They will never make Olivia gay 'cause her heterosexuality has already been established. If she decided to "jump the fence" then they would have to focus on her personal life and we all know they would NEVER do this!! Heck…the show's been on 5 years and we've seen the interior of Olivia's apt…what…maybe once??

[4.16] SVUFreak107: OMG YOU GUYS ARE CRAZY!!! Mariska/Olivia is not gay no matter what it will just screw up her image in real life and no one will like her. It will take people away from teh show not to it!!!

[4.17] A later poster objects on political grounds, lamenting the casualties of the closet's gendered double binds:

[4.18] SVUAddict: I find it very frustrating when females who are strong and assertive immediately get labeled lesbians. Yes, Olivia is tough and independent, but she's also straight and I've grown tired—in my own life and in Hollywood—of seeing powerful women labeled as gay. To me, at least, it undermines the potential of straight women to possess these characteristics.

[4.19] Meanwhile, what is perhaps the most fascinating response overtly describes the influence of fan production on Olivia's hypothesized sexual orientation:

[4.20] Munchz Hunch: as far as olivia and being gay goes, the only reason i ever thought she WAS gay was because of all the fan fics about her BEING gay! that was what made me question her sexuality…people write fan fics from what they got off the show, and i havent seen every episode, not even CLOSE, so i was wondering after reading those fics if they [Olivia and Alex, etc.] truly WERE gay couples on the show. but that was put to rest after seeing her with cassidy [1.10 "Closure"] and with that reporter dude [1.16 "The Third Guy"]…so i have had my suspicions, but they were all eventually cleared up.

[4.21] In this viewer's hierarchy, fan fiction has substantial authority in the investigation of Olivia's sexuality because it is written by those with particular expertise in reading television's signals. However, diegetic verification trumps these fan interpretations, providing a stable resolution to the mystery (at least if one conveniently overlooks the option of bisexuality, as noted above). When priority is given to clues located inside the television text, the implication is that if some are arriving at the wrong verdict, their viewing strategies must be perverse or deluded. Spank puts this dismissal most succinctly: "This is ridiculous…You lot look for things that aren't there." I would argue, however, that the significance of these processes of looking should not be underestimated: what popular debates such as this one illustrate is that commercial authority over textual conclusions is dynamically negotiated and always provisional.

[4.22] Far from the message board debate in both degree and kind, one fan under the pseudonym Sally Forth composed an elaborate riposte to these sorts of scornful reactions to the proposition that Olivia isn't quite straight. Her exhaustive, expansive, and often excessive "rave," rendered as a static Web page dated 2006 (http://web.archive.org/web/20060423012451/http://www.sallyforth.info/), is an idiosyncratic and remarkable document of vernacular theory, detailing her observations and arguments concerning Olivia's intimacies with lesbian desire through both textual analysis and broader political critique. Covering everything from obscure inside jokes to the moral, legal, and conceptual battles over social issues such as gay visibility and same-sex marriage, Sally's content and links manifest her engagement with fan and media networks even in the absence of technical interactivity. Confirming that "on every SVU-related message board I've seen, the issue of Olivia's sexual preference comes up at some point," she gripes, "Any time I posted that Olivia might be gay or bi, well, let me say, I got my ass kicked. 'You're crazy. That scene/look/action/appearance could mean anything. Olivia Benson is not gay. Get over it!'" Sally, like some of the posters quoted above, is not optimistic about the prospect of Olivia coming out within the constraints of commercial television, writing, "IMHO, TPTB [The Powers That Be] will keep Olivia as she is. No boyfriend. No girlfriend. That is the only way to avoid alienating any fans." But she nonetheless champions the integrity of spectatorial practices, asserting, "The whole point behind subtext is that people can enjoy the show however they wish, without having someone tell them that they're wrong or reading things into the show that aren't there." Her claims are not based solely on a revaluation of fan readings, however: she supports this call for interpretive pluralism with a humorous but meticulously impartial account of the textual evidence on both sides of the question "is she or isn't she?", making the case that those who consider the inquest over at the first glimpse of an on-screen boyfriend just aren't looking hard enough. That is, although she self-identifies as a lesbian fan, for Sally too, the figure of Olivia's lesbianism is a shifting jumble of diegetic references and absences, audience competencies and investments, industrial conditions, and political context that is not easily stabilized, and at the same time not easily dismissed. Both ephemeral online discussions and Sally's more concerted manifesto are artifacts of fans' struggles with the complexity and contradictions of the project of representing or locating lesbian desire in the televisual landscape—its frustrations and its inexhaustibly generative potential.

5. Textual orientation

[5.1] The fluctuating topology of television's text and metatext, denotation and connotation, canon and fanon is a conceptual challenge to sexuality as an epistemological project, but it also concretely intrudes at the points of contact between the territories of production and consumption on either side of the screen. I have already noted television's formal and historical inclination as a medium that endeavors to be coextensive with everyday life, to unfocus comfortable demarcations of all sorts. Jane Feuer notes, "Television as an ideological apparatus strives to break down any barriers between the fictional diegesis, the advertising diegesis, and the diegesis of the viewing family, finding it advantageous to assume all three are one and the same" (1986:105). The commercial advantage of this blurring of fiction and reality, always manifested in the flow between programs and commercials and between programs and behind-the-scenes gossip and personalities, becomes increasingly conspicuous as the Internet renders the perspectives of fans and media professionals increasingly accessible to each other. The San Francisco Chronicle infamously reported that SVU executive producer Neal Baer "admits tweaking fans with veiled references to Sapphic love. 'We read the fan sites. We know that people are into the Alex-Olivia thing. All the codes are in there'" (Chonin 2005)—a confession that is less interesting as an outright legitimization of subtext than as a junction in the ongoing course of Olivia-centric negotiations across shifting valences of textual meaning and power. The fourth wall was even more dramatically breached when, after her tremendous investment in analyzing Olivia, Sally Forth contacted Hargitay to share her commentary. Hargitay responded directly and allowed Sally to post a synopsis of their phone interview on her Web page. Such close encounters between the organs of fan production and the organs of media production are a corollary of the industry's intensifying attention to modes and sites of fannish engagement.

[5.2] Among Hargitay's "candid and sincere" answers: "She greatly appreciates all the mail she receives, including the letters from gay viewers who relate to Olivia Benson…It saddens her to think she has hurt anyone's feelings…The fact that Olivia is seen as ambiguous is interesting because her character clearly engages the viewers' imagination." Her apologia alludes to a comment Hargitay made on Late Night with Conan O'Brien in April 2003 that turned out to be a PR blunder—one that addressing the fandom via Sally Forth might rectify. During her interview with O'Brien, Hargitay expressed what some took to be homophobic discomfort with aspersions cast on her own heterosexuality by lesbian readings of Olivia. The phenomenon she reacted to—a certain slippage between Olivia's character persona and Hargitay's star persona—relies on a multifaceted intersection of real and fictional worlds: the parallels between Olivia and Hargitay as professional women; as antirape advocates (http://mariska.com/resources); as alleged lesbians. If we accept the procedural's premise that the truth must be precisely what is not visible at first glance, following Olivia's (and Hargitay's) trail routinely leads to probing for the real person behind her.

Video 2. Mariska Hargitay on Late Night with Conan O'Brien (April 2003).

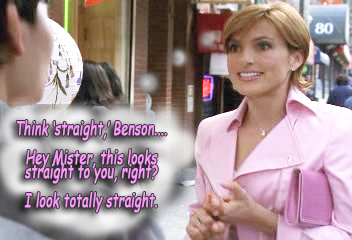

[5.3] The Conan incident, in this broader context of actor/character intermixture, catalyzed a conspiracy theory that a fan community collectively elaborated on over SVU's ensuing seasons. They hypothesized that the explanation for a pronounced transformation in Olivia's gender presentation was a systematic "de-dykefication" orchestrated by Hargitay. Among the clues cataloged: the lengthening of Olivia's near–crew cut through awkward stages of dyed and hair-sprayed shags, mullets, and bobs; fake tanning and other unfortunate skin treatments; an overall shift to a more feminine wardrobe; even a noticeable change in the way Olivia walks. Although we cannot solve the mystery of the motives behind what amounted to an assault on the character beloved by lesbian fandom, fans' arguments for a guilty verdict (figures 4 and 5) are themselves evidence of a volatile collision of instabilities and inequalities around television's deployment of the subtextual closet, exacerbated in an era when television's own identity is increasingly suspect.

Figure 4. Graphic by aqua_blurr, posted on October 18, 2004, to the LiveJournal community ob_fangrrl. This image adds a humorous internal monologue to a screencap by aleatory_6 in which Olivia is dressed up in high-femme "drag" for an undercover sting (6.02 "Debt"). [View larger image.]

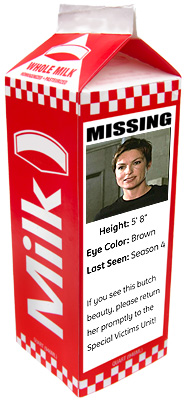

Figure 5. Graphic by newbie_2u, posted on November 2, 2005, to the LiveJournal community ob_fangrrl. Fans saw the changes in Olivia as so dramatic that they declared the original character a "missing person." [View larger image.]

[5.4] If, in its early days, slash was sometimes condemned as character rape, for fans of "butch" Olivia, her feminization was the true violence, and their vehement expressions of rage and betrayal were commensurate with such an atrocity. In an impassioned post on the subject dated September 22, 2005, LiveJournal blogger trancer21 captures the intractable, intolerable position that results:

[5.5] I really feel that the consumption of fandom has changed my opinions. Because, while reading these MH [Mariska Hargitay] articles, seeing the pictures, I get the picture of a woman who's trying to reclaim ownership of her character from the fans who see the character as gay. There is no separation between actor and character…And it pisses me off because Olivia Benson is NOT the property of Mariska Hargitay. Once those little images leave the cathode ray clutter, it becomes the property of the audience.

[5.6] In other words, the entanglement of actor and character is itself inextricable from the entanglement of the cathode ray and the audience that generates interpretive concords about Olivia and Hargitay's text and paratext, and these epistemological snarls are in turn ensnared in the economics of the industry. For Olivia is certainly not "the property of the audience" proportionally to her status as property within the apparatus of corporate ownership, buttressed by the legal mechanism of copyright and the system of mass distribution and financing. However, the devices of ownership are still unable to contain her in these bounds, and in keeping with the futility of binary enclosure, the siege of Olivia on screen stimulated an efflorescence of snark (that is, sarcastic criticism) online. Following the conjecture that elements of Mariska Hargitay's persona were forcibly grafted onto Olivia Benson, much of it lampooned the resulting monstrous mutant: Oliska Hargenson. As far as I can tell, this portmanteau was coined as the punch line of the parodic fanfic "It Ain't Her" by newbie_2u, posted on October 4, 2005, to the LiveJournal community ob_fangrrl, which features Detectives Munch and Tutuola investigating Olivia's apparent disappearance. It is an example of a smattering of meta stories treating this theme, and others often refigure the extratextual battle fans framed in terms of Olivia versus Mariska as an angst-ridden erotic drama of Olivia/Mariska. One rendition by giantessmess posted on September 10, 2005, to ob_fangirl reverses the familiar hierarchy, portraying Olivia as the stronger and more real double, and Mariska as the television viewer who falls prey to her charms:

[5.7] She grew Olivia out, strand by re-touched strand. She tried to stop herself from disappearing, as she felt the camera draw her inside it…But she still felt herself fading. Watching Olivia, failing to see herself, falling helplessly in love with her possessor…Mariska was afraid to sleep. She was afraid that she wanted Olivia to find her. Afraid of her dreams that bled into reality.

[5.8] Here, it is Olivia who possesses Mariska, in both spectral and propertied senses, infiltrating "reality" with uncanny spectacle. It is not incidental that the memetic conspiracy in which these artifacts participate was largely located in a LiveJournal community: this and comparable distributed, interactive Web networks haunt television like fanon Olivia haunts Mariska, perturbing the economies of corporate possession. In this context, paranoia on both sides about Mariska and Olivia commingling seems well founded. Today, TV's existence depends on its interpenetration with fan fictions.

6. My girlfriend Olivia

[6.1] After previewing selections from the original version of this essay while it was a work in progress, Sally Forth jokingly told me that she "can't wait to get to the 'Olivia is really gay' part" (personal correspondence, June 26, 2004). Needless to say, there is no such part. My analysis has not solved any of the enigmas of the closet, whether on the axes of straight/gay or TV/Internet, or any of its other intertwined polarities. The price to be paid for such complexity is a refusal of the sort of politics of representation that Sally Forth rousingly renders in her 2006 rave:

[6.2] In order to be free, we must be seen…For this reason, the struggle to become visible has been part of every civil rights movement in this country. Conservatives are constantly fighting against the realistic portrayal of gays and lesbians in the media. By making us invisible, they can define us, control us, and stop us from fully participating in this culture…It is why the closet is so destructive.

[6.3] While this call can be deployed strategically, the threshold of the hidden/visible is itself caught up in the closet's structural logic. As the case of Olivia Benson demonstrates, seeing a lesbian on television is far from a simple procedure, and what looks like a realistic portrayal is contingent on localized viewing strategies. The closet is their terrain, and despite its oppressive fickleness, I'd venture that it generates as well as conceals truths, opens as well as closes doors.

[6.4] This returns me to the provisional distinction between what I would qualify as lesbian versus queer readings. As a TV fan, I occupy both positions, and I can appreciate the desire for a sexuality—lesbian—that appears conclusive and legible as a political identity. Given that a queer perspective thwarts closure and boundaries, it is understandable that it might be considered pessimistically as its own sort of "closet of connotation" (Doty 1993:xii), refusing any authoritative findings and relegating all meanings to perpetual subtext. Arguably, however, fandom's drive is itself a queer one because it is openness that inspires the creative engagements and interventions that aim to but never fully succeed at filling in a program's gaps. This tension between lesbian and queer modes, without any final resolution, defines SVU femslash fandom during its most dynamic era. In the context of media studies, I am committed to a queer methodology at the cost of any decisive outcome because I believe that it accentuates the dimensions of fan production that resist, even if they do not topple, the epistemological regime that is most convenient for capitalism. This is perhaps little consolation, though, to the bitter fans who called for Olivia to come out, struggling with TPTB over ownership of her image.

[6.5] As my own rejoinder to those who insist on enforcing Olivia's heterosexuality, my work here is conceived as engaging with rather than merely commenting on this expansive and interactive battleground. This essay, which has been posted online in various earlier versions since mid-2004 and which itself may be recognized as a node in the diffuse matrix of Olivia fandom, also has permeable boundaries and is open to wanton intersections and continual reconfiguration. If in one sense I've created a colossal tease for those who may wish to prove conclusively that Olivia is a lesbian, in another, this ardent critique has been the supreme erotic encounter between Olivia (my fellow detective) and me, in defiance of the frontier dividing the real world from the one on the TV or computer screen—and what could be more substantial evidence that Olivia swings my way than that? Nonetheless, it remains unclear how Olivia can be my girlfriend within an academic project, or how such a project can satisfy fandom's desires.

[6.6] Part of the puzzle is differentiating serious work from salacious leisure, a margin that late capitalism renders ever more coy. The explicit incorporation of fan labor into the media industry undermines the distinction between professional and amateur production, which debunks the fantasy that consumers inhabit an entirely separate sphere from producers. And on the flip side of this blurred boundary, it can be in the promotional interest of creators to present themselves as familiar with (and to) fandom. Meanwhile, as consumer engagement is increasingly valued, the importance of desire as an interface between media commodities and their reception, as a form of productivity in itself, comes to the fore. The industrial escalation of television's identity crisis makes it imperative to consider the confluences between outside and inside, public and private, reality and fiction that lend the libidinal economies of slash and closets their powerful vitality. What I offer here is my own fannish reworking of some of the scholarly traditions of television studies that intensifies their linkages with these emerging systems.