1. Introduction

[1.1] By some measures, Undertale (Toby Fox, 2015) could be called one of the most beloved video games of all time. In the months following its release, the game proved immensely popular with players, reviewers, and games industry professionals alike. It was voted "Best Game Ever" on the popular website GameFAQs (Frank 2015), beating out classics from canonical game series like Zelda and Mario. It was, for a period, the highest rated PC game of all time on the review aggregate site Metacritic.com (Dale 2015), and it was nominated for Best Debut, Best Narrative, and the Innovation Award at the 2016 Game Developers Choice Awards. As of December 2017, Undertale had sold more than two and a half million copies on the online distribution platform Steam. In response to the game's popularity, Kotaku reporter Patricia Hernandez (2015) wrote, "I've never seen a game this young command so many dedicated fans."

[1.2] Among the factors that make this success story so unexpected is the wide range of players from across varied sectors of games culture who have expressed their adoration of the game. As Adrienne Shaw has written, the term games culture, which describes the network of players, practices, communities, and discourses that surround video games, is often used in an overly simplistic sense, replicating the misconception that games culture can be understood as synonymous with prototypical and often stereotypical gamer identity (Shaw 2010). In fact, contemporary video game cultures contain numerous subcultural sectors and divergent perspectives, making it rare for a game to achieve the quality that has been attributed to Undertale: its seemingly universal appeal (Smith 2015). Indeed, Undertale has been embraced by a wide array of players who represent a spectrum of positions within games cultures and the broader sociopolitical landscape of video games—though admittedly, even in the face of its widespread popularity, some naysayers have decried Undertale as a game for "social justice warriors" (Hernandez 2015). At a time when friction between progressive and reactionary corners of gaming have reached new heights, in large part because of the harassment campaign #GamerGate (Wingfield 2014), Undertale seems to have taken on the role of the great equalizer, the game that almost everyone can agree on enjoying. However, there is another key feature of Undertale that makes its so-called universal appeal more surprising still: its notable inclusion of LGBTQ content and queer themes.

[1.3] As many have observed, homophobia has long been a problem within video games as a medium, the games industry, and many areas of games culture (see Gaming in Color 2015). Even in more recent years, as large, influential AAA game studios have begun to acknowledge the importance of increasing LGBTQ representation in games (Makuch 2015), and as queer gaming communities have flourished around events like GaymerX (Hosea-Small 2016), it is common to witness considerable resistance to the inclusion of queer content in games, especially from those sectors of games culture dominated by white, straight, cisgender men and boys, still commonly presumed by many content producers to be the core audience for video games (Fron et al. 2007). While games culture itself has often been defined against a notion of the more general, societal mainstream (Shaw 2010), there also exists within games culture a set of hegemonic ideologies and a perceived gamer default. This is related to what Mia Consalvo has described as "toxic gamer culture," in which "misogynistic…patriarchal privilege attempt[s] to (re)assert its position" over women and others considered outsiders (Consalvo 2012). In much the same way that toxic gamer culture has lashed out against women, it has also aimed its attacks at queer people. For instance, homophobic backlash can be observed in heated player responses to recent announcements from Blizzard and Riot Games that their titles Overwatch (2016) and League of Legends (2009), respectively, include gay characters (Frank 2016; Crecente 2017). Indeed, the gamer identity itself is fundamentally tied to straightness. As Megan Condis has argued in her work on fan responses to LGBTQ content in BioWare games: "True gamers and fans are assumed to be straight…or, if they are queer, it is assumed that they will remain in the closet" while participating in gamer community spaces (2015, 199).

[1.4] How, then, has Undertale, with its LGBTQ characters and queer themes as described below, achieved its widespread success, which extends into corners of gaming that have otherwise proven themselves actively hostile toward diversity? Here, I seek to answer this question by turning a critical eye toward Undertale's reception in these spaces. To understand the ways in which the game has been received, and how these players have responded to the game's LGBTQ content, I look at the rhetoric that both reflects and perpetuates the terms of the game's reception. I take as my illustrative examples of this discourse a representative selection of game reviews from websites that cater to an imagined gamer readership, as well as forum threads from the Undertale subreddit, since Reddit itself is notorious as a breeding ground for toxicity in games culture (Quinn 2017). Together, these examples gesture toward a larger set of rhetorics and logics through which Undertale has been understood and indeed rendered acceptable to segments of games culture that are often unwelcoming toward queerness. This analysis also opens the door to a broader critique of LGBTQ representation in video games. Increasing LGBTQ representation is commonly presented as the ready-made answer to problems of homophobia and queer marginalization in games. As the case of Undertale suggests, however, the cultural impact of queer video game content has its own potential limitations. Even a game with queer characters, queer plotlines, and queer approaches to game design can be recast by players resistant to diversity.

[1.5] It is perhaps tempting to view the phenomenon of Undertale's universal appeal with optimism, as some have done (Speight 2015), by interpreting it as evidence of a promising shift away from discriminatory attitudes in games culture. However, as I demonstrate here, a closer look at the rhetoric that characterizes the game's reception within primarily straight, cisgender male player communities tells a very different story. Far from embracing or even addressing the game's LGBTQ content, this rhetoric seems to almost entirely ignore Undertale's queer elements, while turning an insistent focus on the elements of the game that jibe with dominant straight gamer culture. Given this, I argue, Undertale's popularity does not speak to an increasingly tolerant attitude toward LGBTQ representation but rather an active straightwashing, characterized in large part by queer erasure and a reframing of the game's key aspects. The rhetoric of this reception attempts to overwrite Undertale's existence as a queer game, disavowing its LGBTQ elements and remaking it as a game that conforms to the values of gamer masculinity. Such rhetoric accomplishes this shift by foregrounding elements of the game that are culturally coded as straight and male: namely, its challenging gameplay, innovative design, and nostalgic appeal for real gamers. This straight reimagining of Undertale stands in stark contrast to the game's queer interpretations, suggesting that it has earned its universal appeal not because of but rather in spite of its LGBTQ content.

[1.6] At this crucial moment in the history of video games, when the medium seems truly poised to move beyond its long-established status as the territory of straight men and boys (Cross 2016), and when the call for increased LGBTQ inclusivity in games is becomingly increasingly audible across the games industry, games academia, and games culture (Ruberg and Shaw 2017), Undertale stands as a cautionary tale that speaks to the potential limitations of LGBTQ representation in video games. The push for a greater presence of LGBTQ characters and romances in games is important work that can be highly meaningful for queer players; it also represents a key element of the fight for social justice in the medium. However, as many queer game studies scholars have argued, LGBTQ representation is not the only form that queerness can take in video games, and LGBTQ representation itself often merits critique. The straightwashing of Undertale suggests that queer progress in games culture—which is often characterized as the increased presence and improved quality of LGBTQ characters in games with widespread receptions (Karmali 2014; Parlock 2016)—is in fact complicated and precarious. Indeed, the straightwashing of Undertale raises many questions that extend beyond this individual game. What is the value of diverse representation in a video game if that representation can be ignored and overwritten by its players? Even as it represents LGBTQ identities and queer desires, is there something lacking in the type of queer representation that a game like Undertale offers, which allows it to be straightwashed? Having confronted the potential limitations of LGBTQ representation, what alternative ways can we find for moving forward in the work of promoting greater queer inclusion and social justice in video games?

2. Undertale as queer video game

[2.1] While much of the rhetoric around Undertale's popular reception has ignored and overwritten its queer elements, as will be demonstrated below, LGBTQ content and queerness more broadly are in fact prominent in the game. These queer elements take many forms, ranging from the representational (e.g., the inclusion of nonheteronormative characters and romance storylines) to the interactive (e.g., the design of ludic systems that resonate with LGBTQ experiences and queer theory). As Spencer Ruelos has argued, Undertale "communicates queer values through its diverse narrative representations and game mechanics… In Undertale, the representation of queer genders and sexualities at many times is inseparable from the player choices and mechanics of the game" (Ruelos 2017). In this way, Undertale can be said to embody many of the tenets of a queer video game as described by scholars and designers contributing to the burgeoning critical paradigm of queer game studies (Ruberg and Shaw 2017). As Colleen Macklin writes in "Finding the Queerness in Games," a game's queer aspects may be found in its characters or storyworlds, but also in what a queer game does and "lets us do," such as by "subverting our expectations of control and agency as players" (Macklin 2017, 250–52). By including queer mechanics as well as queer representational elements, Undertale also embodies what Edmond Chang has called "queergaming," presenting players with a world in which queer identities and desires are common, yet which goes beyond the "superficial [queer] content" included in many AAA games that include LGBTQ representation (Chang 2017, 17). The queerness of Undertale also extends out from the game into its fan communities. On websites like Tumblr, queer game fandoms work to highlight the queer aspects of the game through the creation of fan lore, fan fiction, and fan art. Together, these factors make Undertale a notably queer game.

[2.2] The first and perhaps most direct way in which queerness manifests in Undertale is through the game's representational elements. An important example of this LGBTQ representation, the game features a protagonist of nonbinary gender who is referred to using they/them pronouns. Undertale begins when this protagonist, a human child, falls into an underground realm of monsters (figure 1). Over the course of the game, the child progresses through many fights and plot twists to find their way back to the surface. Though the inhabitants of this realm are called monsters, they are rarely monstrous. Instead, they form a charming, motley cast of characters that come in all shapes, species, and quirky personalities. As a society, the monsters are struggling with their own historic conflicts, but individually they are also equally concerned with the everyday trials and tribulations of making friends, wooing love interests, seeming cool, and doing right by others. Along with talking with characters and exploring, the player's primary interactions consist of attack encounters with enemies: standard fare for role-playing games, but with some important changes. In addition to a traditional fighting system, in which players select from a series of actions, Undertale incorporates a "bullet hell" minigame feature; players must navigate a small heart around incoming obstacles in the midst of the turn-based fight. Also notable is the list of possible attacks and other options that a player can choose from during battles, which include distinctly nontraditional options like flirt, compliment, and (in the case of certain canine enemies) pet. The game's tone is humorous but also sincere, and its style is simultaneously nostalgic, exuberant, and absurdist.

Figure 1. The player-character, a child of nonbinary gender, begins a journey in the underground world.

[2.3] Undertale's gender nonbinary protagonist is far from the only queer figure in the game. Many other characters also hold LGBTQ and otherwise nonheteronormative identities. Indeed, the large number of such characters is one of Undertale's most unique representational elements, especially given that most video games—with the exception of those emerging out of what has been called the "queer games movement" (Keogh 2013)—still rarely include multiple LGBTQ characters, contributing to what Todd Harper has described as the treatment of diverse characters in games as "unicorns" (Harper 2015). By contrast, Undertale takes place in a world where queerness is common. In an email exchange, the game's creator, Toby Fox, had this to say about the game's queer elements: "I'm really glad the game has…given kids exposure to a story where queerness is normal" (personal communication, April 2017). As an example of this normalizing of queerness, one of Undertale's most prominent narrative subthreads focuses on the budding romance between Undyne, a fierce lady fish creature, and Dr. Alphys, a female scientist dinosaur. By making the right choices in combat and conversation, the player can earn the "best ending," in which Undyne and Dr. Alphys officially become a couple. The character Mettaton is another important queer figure in Undertale. Mettaton begins the game as a boxy, rolling robot gameshow host—but later trades his mechanical form for a human-esque body with feminine curves and a swooping hair style. In both of his forms, Mettaton is presented as not conforming with dominant binary norms of gender identity and presentation. In the case of Mettaton, Undertale's queer fan communities have been instrumental in surfacing this character's queerness and establishing it as canon—or at least as fanon. Many queer fans have argued for Mettaton as a transgender character (https://lgbtqgamearchive.com/2017/02/12/mettaton-in-undertale), and fan art that highlights Mettaton's non-gender-normative appearance is a prominent staple of the Tumblr fandom that surrounds the game.

[2.4] LGBTQ representation in Undertale also extends to its minor characters. The game-world is populated by a large array of briefly encountered nonplayer characters whose gender identities are indeterminate or who express queer romantic interests. In addition, many characters manifest queerness through their nonnormative bodies and alternative modes of desire, both of which are recurring themes in the game. Some of these character designs are playfully bizarre, such as a monster who looks like a wobbly Jell-O creation. Oftentimes, the bodies of these monsters both reflect and disrupt expectations around gender and sexuality—suggesting an implicit link between monstrousness and queerness. One example is Aaron, an enemy who is ostensibly part horse and part buff merman (figure 2) and who attacks by flexing his muscles. Such elements are part of the game's humor, but they also represent a genuine fascination with questioning and indeed queering bodies. To the extent that these characters speak to diverse representation, they also push against established categories of diversity, exploring difference through iterations of the body that resist accepted social categories of identity. Similarly, attraction and interpersonal connection take on notably varied forms in Undertale. Flirting, for instance, is often used to complicate standard models of intimate relationality. At one particular moment, the player can choose to telephone Toriel, a parental figure who guides the player through the game's opening sequence, and either flirt, call her "mom," or both. At such times, the game playfully blurs clear-cut distinctions between normative standards of intimacy, such as parent-child relationality versus relationality between lovers.

Figure 2. Aaron is part horse and part merman, and fights by flexing, a sign of Undertale's interest in nonnormative bodies.

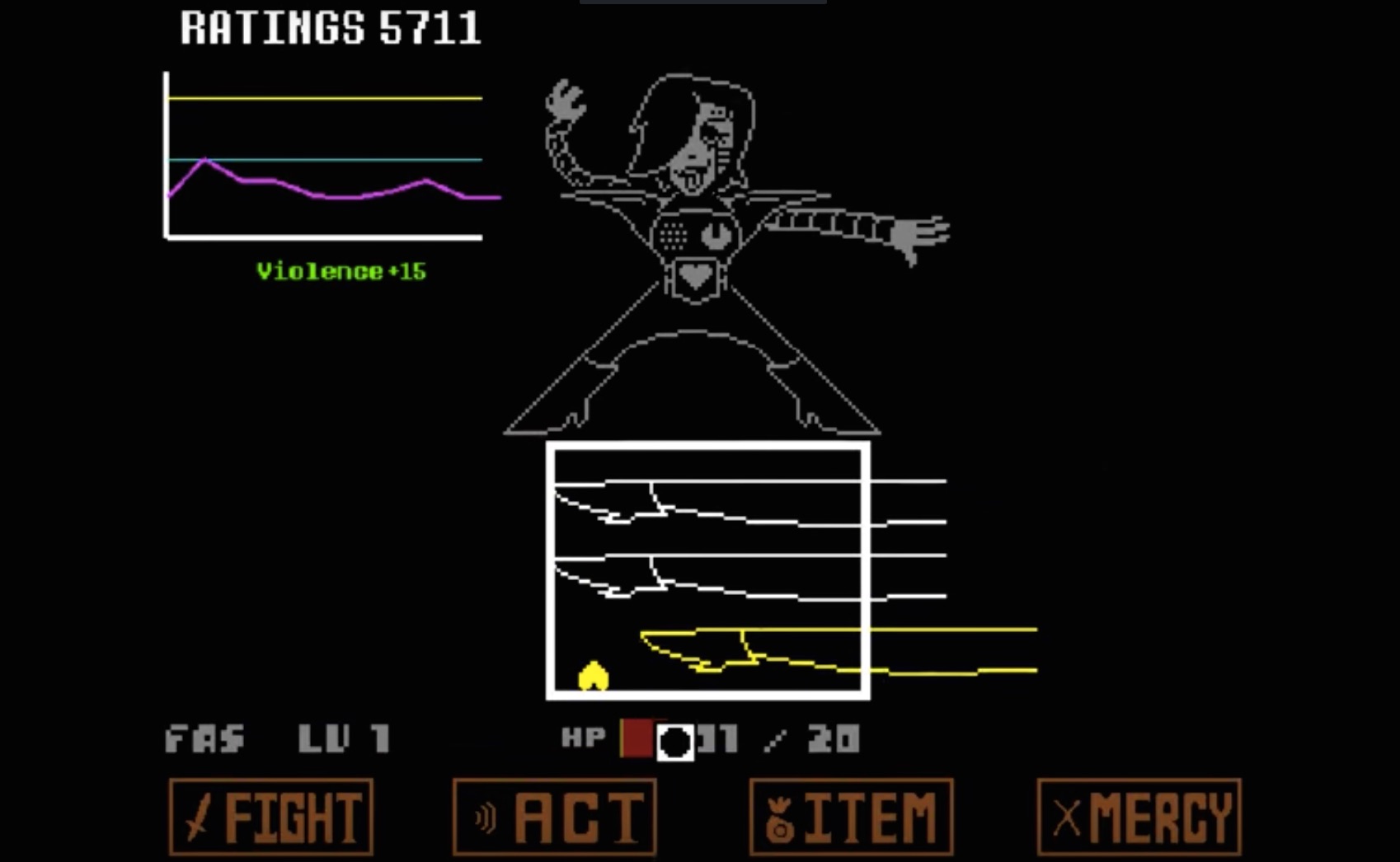

[2.5] In addition to its inclusion of explicitly LGBTQ characters and themes, Undertale presents subtler queer representational elements. As Adrienne Shaw has noted, in-game representations of queerness can take many forms, such as a poster for a gay bar hung in the background of an otherwise seemingly straight area. "These things aren't necessarily part of the main text," Shaw points out, "but they're part of the universe that the text creates" (Ruberg 2017, 168). Undertale partially performs the creation of its own universe by integrating coded references that signal the game's engagement with queerness. For example, when the player faces off with Mettaton in his nonrobot form, the battle is dotted with queer-coded markers. Some of the obstacles that the player dodges in the "bullet hell" minigame are high-heeled boots (figure 3) and a spinning disco ball, calling to mind a nightclub scene or a drag performance. Mettaton himself can clearly be seen vogueing—moving his arms and legs into quick, dramatic poses that reference drag balls like those depicted in the documentary Paris Is Burning (1990). Through these touches, the game places itself in dialogue with traditions of camp, drag, and other performances tied to LGBTQ identities.

Figure 3. The player's battle with Mettaton is marked with queer-coded imagery such as high-heeled shoes.

[2.6] At other times, the links between Undertale and queer culture relate to a shared ethos rather than visual references. Even as the game foregrounds fighting, it draws heavily from the language of contemporary consent culture, which has a strong presence in online queer communities (Femifesto 2016). If the player follows the skeleton guard Papyrus home for a date, Papyrus confesses, "I'm sorry. I don't like you the way you like me." This moment stands out because, while it is not uncommon to see romance between players and characters in video games, it is far more standard for games to treat these relationships as rewards (a canonical example is Mario's ongoing quest to win his beloved Princess Peach)—or, as Jetta Rae (2015) has noted, as "conquests." Undertale resists this model, giving its nonplayer characters the right to say "no" and challenging the presumption that a player should have agency over the desires of others. In this way, the game not only includes nonheteronormative characters and stories, but also itself resists the problematic cultural expectations around sexuality and gender that video games often replicate.

[2.7] Lastly, Undertale can be understood as a queer game through its many resonances with queer theory, which are often embodied in the game's interactive and systemic elements. These resonances are multiple and nuanced, and merit more scholarly exploration than space affords here; the following examples represent some potential pathways for future work. One is the way the game enacts queer world-building and suggests a "utopia organized around principles of nonviolence, intimacy, and communication" that echoes the notion of queer utopia expressed by José Esteban Muñoz (Ruelos 2017). Another example can be found in the game's engagement with the imagery of glitches. During a boss battle, Flowey, a menacing character and a force of chaos, simulates shattering the screen and claims to have corrupted the player's save file. In these moments, Undertale plays with the queer glitch as that which, as Jack Halberstam has written, "tears down" expectations and creates space for alternative ways of being in games (Halberstam 2017, 197). At times, the interactive elements of Undertale also resist the neoliberal narratives of queer progress that have been critiqued by theorists like Heather Love and Elizabeth Freeman (Love 2007; Freeman 2010). Among the game's unique features is the fact that it allows players to proceed past enemies without killing them. Yet sparing one's enemies also comes with a price: pacifist players earn no currency or experience points in their fights, making them increasingly vulnerable as battles get harder. In this way, the game offers a vision of antiaccumulation that challenges the expectations of the heteronormative, capitalistic society from which the game emerges.

[2.8] As this overview of Undertale's queer representational, thematic, and conceptual elements suggests, the presence of queerness in the game is both notable and pervasive. My goal in offering this overview, which is far from exhaustive, has been to demonstrate the importance of LGBTQ perspectives and queer thinking to Undertale. This articulation of Undertale as a queer game stands in striking contrast to the writing on the game that has circulated in mainstream gamer spaces, as represented by the examples below. The contrast between these two rhetorics highlights the notable absence of discussions of LGBTQ representation in this discourse, underscoring how this discourse has enacted an erasure of queerness and a subsequent straightwashing of the game. While it is possible and even likely that the game's subtler queer elements, such as its references to queer cultures and its resonances with queer theory, may go unnoticed by nonqueer gamers, it is hard to imagine that the game's explicit representations of LGBTQ subjects and desires could be easily overlooked. Leaving these elements out of the discussions that have taken place around Undertale in predominantly straight, male sectors of games culture represents more than an oversight, a blind spot, or even a simple (if worrisome) attempt to pretend the game's queer elements are not there. Rather, it entails an active attempt to reimagine the game itself as straight.

3. The straightwashing of Undertale

[3.1] Given Undertale's many queer elements, it is notable that the discourse that has surrounded the game in otherwise reactionary sectors of games culture, where it has been the subject of numerous game reviews and online community discussions in the three years since its release, seems to show almost no engagement with—or even acknowledgement of—the game's LGBTQ representation. Of the 43 reviews of Undertale listed on Metacritic, the majority of which have been published by websites like IGN, The Escapist, Game Informer, and PC Gamer that cater to an assumed gamer readership, a mere three mention topics of gender or sexuality, and then only in passing, most often to note that the game's protagonist is "gender ambiguous" (Plagge 2017; McDonald 2015; Forman 2015). Yet, as a closer look at the rhetoric of these reviews and community discussions reveals, this discourse has not simply overlooked Undertale's queer elements. To the contrary, through queer erasure and a subsequent reframing of the game, this rhetoric has actively worked to draw attention away from the game's queerness and rewrite Undertale as heteronormative—effectively straightwashing the game.

[3.2] Like whitewashing, the process through which social phenomena or works are stripped of their connection to people of color, straightwashing entails a symbolic wiping away and subsequent painting over of a work's LGBTQ aspects. A straightwashed work becomes an object of appropriation and colonization by representatives of the gender and sexual status quo. Edmond Chang has approached the issue of straightwashing video games from the perspective of game development, by looking at how the designers of games like FrontierVille (Zynga, 2010) and World of Warcraft (Blizzard, 2004), which also have large gamer followings, have "fail[ed] to expand or include queer content," replacing moments of queer possibility with "ostensibly stable stereotypes and milquetoast representations of normative love, desire, and heteronormative relationships" (Chang 2015). The case of Undertale demonstrates a second way in which a video game can be straightwashed: through its critical and player reception. For examples of the rhetoric that enacts this straightwashing, I analyze the discourse found in a representative sample of game reviews, as well as forum threads in "true gamer" (to echo Condis's term) spaces. Game reviews are an important site of critique and a valuable window onto games culture more broadly because, as Clara Fernández-Vara has argued, many gamers rely on game reviews as their primary sources for understanding video games (2015); from these reviews, they draw much of their thinking about the medium and its meaning.

[3.3] If the vast majority of reviews of Undertale do not talk about queerness, what do they talk about? A survey of these materials reveals a key set of recurring themes that, though they may not appear at first to relate to gender or sexuality, in fact work to establish Undertale as a heteronormative game. The first example of these themes is a focus on the choices between violence and mercy that Undertale offers. Whereas most video games require players to kill their opponents in order to proceed, Undertale gives players the option to spare their enemies. Indeed, in interviews, game designer Toby Fox has pointed to the idea of creating a RPG in which players can choose not to kill as one of his primary goals in developing the game (Isaac 2015). In Undertale, players' decisions to kill or spare opponents has real repercussions. Many of the so-called enemies that the protagonist faces are also friends, and their presence or absence can seriously change the game's narrative. Unlike in most video games, where players can wipe their past play-throughs and restart the game, in Undertale, a player's history is never entirely erased from the game's memory. From this basic decision, to kill or to spare, two opposite approaches to playing Undertale have emerged. In the first, which fans call the "pacifist run," players attempt to complete the game without killing any opponents. By contrast, in the "genocide run," players kill all enemies. This is the core of what is referred to as Undertale's morality system.

[3.4] Undertale's morality system does indeed meaningfully question accepted norms of aggression and success in video games. However, the rhetoric that reviewers have used to describe the ethical choices with which the game presents the player demonstrates how discussions of Undertale's morality system have also been used to recast the game in ways that align it with heteronormative gamer masculinities. This can be seen, for example, in a review from The Escapist, in which Angelo M. D'Argenio writes about the player's choice to kill or spare their opponents:

[3.5] Why not just hurt people? This is where the morality system comes in. You see, the game characterizes random enemy encounters not as mindless beasts, but as people who have hopes, dreams, and families, just like you…Yes, it is easier to simply kill your opponents than to reason with them, but that's because the game is making a statement. Violence IS easy! Hurting people is easy. Caring about people…is what's difficult. (D'Argenio 2015)

[3.6] While this quote seems to emphasize the social "statement" that Undertale makes through its morality system—that violence has consequences, even in video games—it simultaneously underscores the rhetoric of what is easy (violence) versus what is difficult (caring). Playing as a pacifist is harder than playing as a murderer. As Betsy DiSalvo has observed in her research on constructions of gamer masculinities, performing one's "mastery over the machine," as when playing a video game at the highest difficulty setting, is an important part of presenting oneself as masculine in gamer spaces (DiSalvo 2016). In addition, how difficult a game is to play and how skilled a player must be to progress have long been markers in the division between so-called hardcore and casual games, in which some players (typically cisgender men) are seen as real gamers because they supposedly take games more seriously than casual players (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_v4CIhGcxiY). By emphasizing the technical challenge of being good in Undertale—that is, simultaneously ethically good and good at the game—reviews such as this one sidestep the progressive and arguably even queer potential of the game's morality system and instead recast it as an opportunity to perform oneself as a particularly masterful and by extension masculine gamer.

[3.7] This emphasis on Undertale's morality system also contributes to the straightwashing of the game by reframing its ethical choices through a fantasy of control that replicates existing gendered hierarchies. A review from the website PC Gamer exemplifies this mode of rhetoric, which promises players the opportunity to profoundly alter the game through their choices. Reviewer Richard Cobbett writes, "Going for a genocide run, where you murder literally everybody, essentially turns the whole thing into a pitch-black horror game. A peaceful run meanwhile leads to one of the most charming and heartfelt RPGs ever made" (Cobbett 2015). Rhetoric like this presents Undertale as an opportunity for players, under the guise of questioning morality, to enact new levels of agency over a game world. This imagined agency stands in direct contrast to other, queerer elements of the game, such as the emphasis on consent discussed above, which is founded on the notion that the player cannot and should not in fact have total control over the game world. Ironically, this element of Undertale's mainstream popularity—that it supposedly offers the player considerable control over the game—is actually less accurate than the presence of this repeated theme suggests. The choices that Undertale offers are largely prestructured and preprescribed (Wisp 2015). By incentivizing pacifism, the game steers players toward a specific set of ethics, while allowing them to feel like they are making these difficult but valiant decisions on their own. In such instances, these reviews seem to be overemphasizing the agency that the game affords players, as if preemptively responding to an unspoken anxiety about the fragile artifice of heteronormative masculine power that the game itself inspires.

[3.8] Another prominent theme in these reviews that both sidesteps Undertale's queerness and attempts to establish the game's heteronormativity is praise for its innovative design. For example, in a review for GameSpot, Tyler Hicks writes that Undertale is "one of the most…innovative RPGs to come in a long time, breaking down tradition for the sake of invention" (Hicks 2015). Though much of the LGBTQ and queer content discussed above could itself be considered innovative, the writers of these reviewers choose to focus their discussions of Undertale's innovativeness on its formalism and gameplay mechanics. Along with the game's morality system, its fighting system is commonly lauded for its original combination of turn-based RPG combat and bullet hell games. This emphasis on formalist innovation suggests a straight interpretation of Undertale in two ways. Firstly, by characterizing the game through the rhetoric of innovation, this discourse positions Undertale and its creator Toby Fox among an imagined pantheon of singular great white men and their innovative game creations. As Zoya Street has written, understanding video games through narratives of great men often sidelines marginalized voices and strips games of the complexities of their production (Street 2017). Focusing on Undertale's innovative formalist elements also allows reviews to divert attention away from discussions of the game's representational aspects. In game studies, argue Jennifer Malkowski and TreaAndrea Russworm, "the trend toward code analysis and platform studies [has] inadvertently worked to silence, marginalize, [and] dismiss representational analysis…Representational analysis becomes the less rigorous, less medium-specific way to approach video games, compared to a focus on 'hard-core' elements" (Malkowski and Russworm 2017, 1–2). A parallel type of work can be seen operating in these reviews, which highlight the game's hard-core elements—typically coded as masculine and supposedly unrelated to issues of identity—as a way to "silence, marginalize, and dismiss" discussions of its diverse representational elements.

[3.9] Similar to these reviews' focus on innovation is their recurring discussion of Undertale's nostalgic appeal. Innovation and nostalgia may seem opposed; one looks forward to notions of a changing future, while the other reflects backward to the past. Yet this body of writing on Undertale often directly ties the game's innovative aspects to the fact that it draws from earlier titles, such as Earthbound (Nintendo, 1994). "The same strengths that made Earthbound a timeless classic are the strengths that make Undertale a joy to play in 2015," writes D'Argenio. When it comes to video games, however, nostalgia is inextricable from gender and sexuality. In her work on video game arcades, Carly A. Kocurek has written about gamer nostalgia as gendered, and specifically about how a nostalgic attitude toward arcades reflects a "longing for an adolescent homosocial space…a particularly male place…tied to notions of socializing boys and 'making men'" (Kocurek 2015). One could extend Kocurek's observations about the ties between arcade nostalgia and imagined boyhoods by addressing the fact that nostalgia itself is a matter of cultural and socioeconomic privilege that cannot be separated from identity. Despite talk of the game's universal appeal, Undertale's nostalgic appeal is in fact far from universal. Queer players, female players, and players of color frequently have less access to games during their childhoods, meaning that nostalgia itself is unequally distributed and more likely to be experienced by straight, cisgender, male players. The presumption that all players share the same nostalgic affect when they encounter Undertale overlooks and indeed further marginalizes those whose personal histories do not fit the image of the traditional gamer. Through this emphasis on gamer nostalgia, along with related emphases on challenge and innovation, Undertale is reframed as a gamer's game. In this way, this discourse straight-washes not just the game's content but its intended audience as well.

[3.10] Humor is another tool that is used in these reviews—as well as in other forms of discourse production taking place in gamer spaces—to straight-wash Undertale. Often, a focus on humor in this discourse actively works to undermine the game's queer elements. Tyler Hicks, a reviewer for GameSpot.com, writes, "Even within combat, Undertale layers on the humor. Sometimes you're dodging bullets, but you also need to watch out for frogs…and even the tears of a depressed opponent" (Hicks 2015). Here, the game's humor is described as all-encompassing, a fundamental trait that pervades all elements of the game. Undertale is indeed funny; the game's writing, for example, is full of puns. However, presenting Undertale as fundamentally comic has a particular use in reimagining the game as straight. In reviews like Hicks's, the game's comedic elements are often used to explain its universal appeal. Much of the game's comedy is made up of in-jokes related to video games, which long-time gamers are most likely to understand and find funny. Claiming that these jokes have universal appeal promotes a misguided assumption that all of Undertale's players share this same knowledge. Additionally, in reactionary sectors of games culture, humor is often used as justification for ignoring or outright deriding socially engaged interpretations of video games. To say that Undertale "layers on the humor" without considering the meaning of that humor is to take part in (or at least to provide fodder for) the troubling practice of insisting that games should not be interpreted through cultural lenses because they are "just for fun" (Ruberg 2015). Evan Cooper, writing about the mass audience reception of the television sitcom Will & Grace (1998–2005, 2017–), observed a similar phenomenon. Straight viewers interpreted the show's gay humor, which Cooper describes as "an essential weapon for outsider groups in dealing with discrimination and oppression," as mere "silliness" and "foolishness"—played for straight laughs at the expense of gay characters (Cooper 2003). As in the case of Will & Grace, Undertale's humor is detached from its queer meaning and transgressive potential by its reception and appropriated as a tool for making the game acceptable to straight players.

[3.11] How this emphasis on Undertale as comic marginalizes LGBTQ perspectives is exemplified in a November 2015 forum thread on the Undertale subreddit. The Undertale subreddit is a forum-based community that has remained active even three years after the game's initial release. There, fans of the game share tips, fan art, and other Undertale-related materials. Unlike more queer and queer-friendly Undertale fan communities, such as on Tumblr, conversations that take place on the Undertale subreddit tend to steer clear of social issues in relation to the game. This is in keeping with the tenor of Reddit more generally, many corners of which are home to subcultures that are openly hostile to diversity, and which has been a key site of organizing for game-related harassment campaigns. The thread in question, titled "Undertale's crazy success proves gamers are ready for feminism, queer romance, and progressive values," begins with a link to an opinion piece by the same name published on a website called Game Skinny. Focusing on the relationship between Undyne and Dr. Alphys, the article states that Undertale "has something for pretty much everybody to identify with—all couched in a narrative with feminist elements, strong LGBT representation, and other progressive values" (Speight 2015). Of the 125 comments left in response to this link, most focus on dismissing the claim that the game's popularity is due in part to its "progressive" elements. For example, one commentator insists that, while Undyne and Dr. Alphys may be gay, this is not a "main character trait" and therefore LGBTQ sexuality does not "define them." Another commenter responds with defensive indignation through the performance of incredulity: "How does this game have anything to do with Feminism?"

[3.12] Across the many Reddit comments that attempt to rebuke and disavow Undertale's connection to queerness, along with feminism and "other progressive values," humor emerges as a key theme. Writes one early commenter, "People may be looking [too] deep into this… [It's just] funny if a fish and a dinosaur are girlfriends." Another person follows by insisting, "Can't we just accept that Undertale is just…a good video game?…I can see that certain traits of certain characters inside Undertale could be used as an example for parody of feminism or other 'progressive values.'" This rhetoric demonstrates how an emphasis on Undertale's comedic quality operates as a tool for straightwashing the game. Humor is used to justify a refusal to look beneath the most surface-level interpretation of a video game ("Undertale is just…a good game"). Looking "too deep into this" is presented as the opposite of accepting that it is (supposedly) "funny" for the characters of Undyne and Dr. Alphys to date—thereby placing sexual identity and humor in opposition. A similar logic structures the second comment. This poster attempts to undermine the basic validity of discussing gender and sexuality in relation to Undertale by first rejecting the premise of the discussion and then asserting that, if the game does address feminism, it must only be on the level of parody. By framing the game's engagement with queer identities as parody, this poster repositions Undertale not as a game that embodies "progressive values," as the author of the article with which this thread begins posits, but rather as a game that shares the values of toxic masculine gamer culture, which mocks queerness and feminism (Cross 2016). Together, these comments illustrate how an emphasis on humor becomes a tool for rejecting the game's queer elements and remaking Undertale as heteronormative—or even misogynistic and homophobic.

4. The limits of LGBTQ representation?

[4.1] The straightwashing of Undertale, as seen through the rhetoric of its reception in reviews and in online gamer spaces, suggests that—despite the game's powerful and pervasive queer elements—there may be significant limitations to the cultural impact of increasing LGBTQ representation in video games. Far from reflecting the discriminatory perspectives of a small, niche group, the voices that have enacted the straightwashing of Undertale come from those players who are still considered the default, and who are widely represented in games culture. This means that, despite Undertale's many queer elements, the straight interpretation of the game is arguably dominant in the cultural field that surrounds this immensely popular game. As a cautionary tale, Undertale demonstrates how a game's reception by straight and/or anti-LGBTQ players can problematically resist and obscure its queer representational elements, as well as its values of inclusivity and tolerance. This suggests that increasing LGBTQ representation is not sufficient to shift cultural attitudes toward queerness and video games, and that larger systematic solutions are necessary to bring change to the medium in truly meaningful and lasting ways.

[4.2] Many efforts toward improving the place of queer subjects in video games and games culture have focused on increasing LGBTQ representation in games with wide-reaching appeal. Such tactics are predicated on the logic that, if gamers see more queer characters in the games they play, they will become more accepting of LGBTQ people. Undertale is just such a game—immensely popular across broad audiences—yet arguably the very players who most need to hear its message of queer positivity are those who have ignored it and often actively worked, through their discourse production, to erase it. Unfortunately, the universal appeal of Undertale should not be understood as a sign that reactionary sectors of games culture are becoming more accepting of those traditionally seen as different, but rather that those sectors are capable of retelling the story of a game and its meaning in order to render it acceptable to a gamer mentality that rejects diversity. In this way, the straightwashing of Undertale points to the precariousness of LGBTQ representation in video games. Even a game as queer as Undertale can be and indeed has been appropriated in the service of the heteronormative gamer status quo.

[4.3] At the same time, the straightwashing of Undertale raises a number of questions that merit ongoing consideration in academic, popular, and industry discussions of diversity and video games. How do we decide by what measure a game's LGBTQ representation, or its representation of other marginalized identities, has been effective? While Undertale's queer representational aspects have been straightwashed by significant sectors of the game's reception, its LGBTQ characters and storylines have proven immensely meaningful for many of the game's queer players. It would be a mistake to perpetuate the neoliberal assumption that the representation of diversity in games only matters to the extent that it makes dominant (i.e., straight) culture better. As Naomi Clark has written about the place of queerness in video games, "Games can be legitimized by yoking them to support the institutions of education, propaganda, nonprofit organizations, and behavioral psychology—but should they be yoked?…The queer question must remain: What will we lose in the process as we make additional bids for legitimacy?" (Clark 2017, 12–13). Perhaps the importance of Undertale's queer elements lies not in how the game is received by straight players, but rather in what possible worlds and modes of desire it presents to those who are open to its queerness. And can it truly be said that Undertale's queerness is precarious if the discourse described here has to work so hard to overwrite that queerness? If the importance of the game's LGBTQ representation and queer themes could be so easily dismissed, would these reviews and forum posts need to actively and repeatedly perform Undertale's remaking as a straight game?

[4.4] I conclude here with a final question: even despite its pervasive LGBTQ representations and queer elements, are there inherent limitations to the way that Undertale itself represents queerness that make it susceptible to this type of straightwashing? In Undertale, as Fox himself reports, LGBTQ characters and romances are portrayed as normal. Though these characters do face challenges, they are never discriminated against on the basis of their genders or sexual orientations. On the one hand, the normalization of queerness in Undertale contributes to what Ruelos, as quoted above, describes as the game's vision of a queer utopia. On the other hand, this normalization may be precisely what has allowed nonqueer players to straight-wash the game. Since the game does not address anti-LGBTQ discrimination, or present LGBTQ characters as disruptive to the game-world's status quo, it risks making queerness benign, harmless, and therefore easier to overlook—or laugh off—for players who would prefer to see Undertale as a straight game. I mention this final point not to condemn Undertale for its particular approach to representing queerness, but to suggest that, in order to challenge heteronormative ways of thinking about video games, in-game LGBTQ representation may need to do more than simply show players that queer people exist. This representation may also need to push players to confront difference, power, and oppression as they intersect with LGBTQ lives in ways that cannot be straightwashed out of the game.