[1] Chris Riotta (2016) touches the surface of the years-long rivalry between fans of pop artists Beyoncé and Rihanna, known as the BeyHive and the Rihanna Navy (note 1). As Riotta points out, Beyoncé and Rihanna are two of the most commercially successful black female artists of all time, and the media-constructed competition between them produces the problematic narrative in popular culture of pitting black women against each other. However, Riotta seems to make fans responsible for the construction of this narrative, concluding, "Fandoms, put it to rest. Go spread the good word of your queen in peace." As a black female Rihanna "stan" (note 2), I argue that there is a much larger picture to this narrative—one that was constructed not by fans but by the imperatives of the multiracial white supremacist patriarchy (MRWaSP) (James 2015; hooks [1994] 2006).

[2] Building on what Booth (2014, ¶1.3) describes as "a neoliberal turn in fandom," I first focus on the basic economic principle of competition. According to Foucault (2008, 120), competition is a "formal game between inequalities" that can only be actively produced. This production of competition is significant in Beyoncé and Rihanna fandom, for it produces "their separation, their alignment, their serialization, and their surveillance" (Foucault 2004, 242) as black women in popular culture. Beyoncé and Rihanna are aligned this way in order to categorize black femininities into racialized archetypes that are then put to work by being juxtaposed. As Robin James, using the example of media-generated juxtaposed images of Barack Obama and Osama Bin Laden after the latter's execution, notes, "Some styles of blackness are conditionally incorporated within MRWaSP's privileged mainstream, they don't generate 'otherness' as efficiently as do newer, more exotic and unruly racial identities do" (2015, 154).

[3] The juxtaposition of Beyoncé and Rihanna within media discourses serves a similar purpose, but it also affects the ways their fans practice advocacy in defense of their favorite artist. Fans will defend their favorite entertainers adamantly, as well as "against other readings," as a way to authenticate their status within the fan base and to mutually recognize each other's shared passion (Sandvoss 2005, 105). This sociality—which, "at a collective level, display[s] constants that are easy, or at least possible, to establish" (Foucault 2004, 246), such as the constants that collectives are centered around a specific person and members of the collective will defend that person as a display of their dedication—makes sense in the practice of being a fan. Media discourses make competition the norm in fandom. An example of this norming is music award shows like those of iHeartRadio, MTV EMA, and BET, which introduce award categories such as "Best Fan Army," "Biggest Fans," and "FANdemonium," where fans must compete with each other and vote in order to be deemed the biggest fans (MTV 2017). Consequently, fans and stans perform the labor of placing black femininities in competition with one another by performing particular practices of advocacy—practices that may indeed constitute their fandom.

[4] The media-constructed Beyoncé-versus-Rihanna narrative is not the first time that competition between black women in popular culture has been actively produced and perpetuated—or even fabricated, in Rihanna and Beyoncé's case—by media discourses. For example, "Catwalk Catfight: Tyra Rips 'Hateful' Naomi" (Hutchinson 2004) documents the feud between supermodels Tyra Banks and Naomi Campbell, which dates to the 1990s. This very type of discourse has been used by the news media, celebrity gossip columns, and music sites, as screaming headlines like "Rihanna: Move Over, Beyoncé" and "Beyoncé Furious with Rihanna: New Song a Diss Track?" attest (Taylor 2005; Cox 2015). Words with strongly negative, even violent connotations ("catfight," "rips," "move over," "furious," "diss") sell the idea that these women are angry at each other, illustrating Patricia Hill Collins's (2000) concept of controlling images. Here the angry black woman trope takes center stage, forcing their relationships with one another to be read as a hierarchical struggle.

[5] These controlling images of Beyoncé and Rihanna must be taken into account because they indicate to us how they come to be competitively aligned and how these manufactured fandom fights occur. Beyoncé is an African American woman who hails from Houston, Texas; in contrast, Rihanna is an Afro-Caribbean woman from Barbados who moved to America as a teenager to pursue her music career. Each woman's story plays along a trajectory of race, gender, class, and nationality; the tropes that come with these trajectories have been racialized and positioned within this narrative.

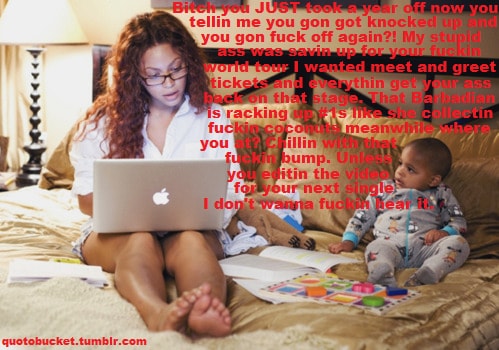

[6] On August 29, 2011, the night that Beyoncé revealed she was pregnant with her daughter, Blue Ivy, at the MTV Video Music Awards, the Tumblr meme shown in figure 1 circulated widely on Twitter.

Figure 1. A Tumblr meme released on August 29, 2011 (https://78.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_lqpnktx53O1qicqv6o1_500.png), after Beyoncé announced at the MTV Video Music Awards that she was expecting her first child. Beyoncé is pictured sitting with a child on a bed with a laptop. Typed in red is a displeased message to Beyoncé.

[7] This message to Beyoncé evokes the archetype of the strong black woman, in which she has "too many obligations but she is expected to handle her business" and must continue "to be everything for everyone else" (Springer 2007, 252). The strong black woman trope goes hand in hand with older controlling images of African American women, such as the black woman who "works twice as hard as everyone else" (Collins 2000, 89). In this meme, Beyoncé is expected to get "back on that stage," as she is a hardworking, high-achieving woman with an all-consuming career; she does not have time to start a family because she "JUST took a year off."

[8] Such messaging falls in line with the meritocratic ideal of neoliberalism: if you work hard enough, you will reap the benefits (Littler 2017). However, black women have to work, and they are expected to work twice as hard. Furthermore, to get back to the trajectories that dictate Beyoncé and Rihanna's competitive alignment, Beyoncé must get back to business because "that Barbadian is racking up #1's like she collectin fuckin coconuts." By acquiring Number 1 songs on the US Billboard Hot 100, Rihanna is here othered as an unworthy Caribbean migrant whose success threatens the progression of African American, middle-class, strong black women. To emphasize Rihanna's migrant status in this context, we are invited to imagine Rihanna "collecting coconuts" as a primitive exoticization of Caribbean life. This example of Rihanna dangerously "racking up #1's" also corroborates Alisa Bierra's point that "though the material circumstances of Rihanna's life are radically different from those of most Afro-Caribbean immigrant women in the United States, her resources did not prevent her public persona from being haunted by these archetypal stereotypes of 'island women.'" These stereotypes mark her as already being "dangerous" and "out of control" (2011–12, 105), as opposed to being respectable and humble like the archetypal strong black woman (Rodier and Meagher 2014).

[9] Figure 1 also exemplifies a deregulated controlling by MRWaSP imperatives, which creates distance between the background conditions of its agenda (an inclusive approach to racist and sexist oppression that has its origins in exclusionary slavery and colonialism) and the activities of fans and their favorite artist. This distance undermines the constructedness of the background conditions of MRWaSP at play. Thus, fans in the BeyHive and the Rihanna Navy who "appear to operate 'free'' of direction" are susceptible to the danger of reproducing archetypal stereotypes of the women of color we stan for by practicing competitive advocacy against another black female entertainer's fan base. This renders unintelligible the background conditions that posit black women as adversaries in popular culture (James 2015, 97).

[10] What the dynamic between Beyoncé and Rihanna fandoms brings into question, as Rebecca Wanzo (2015, ¶2.1) highlights, is the notion that "fan culture stands as an open challenge to the 'naturalness' and desirability of dominant cultural hierarchies" (Jenkins 1992, 18). If fans of black female entertainers, who are competitively juxtaposed by media discourses, are increasingly at the "center of media convergence" (Busse 2009, 356), then we become amplifiers of the consumption, competition, and conditions that naturalize such controlling images. These fandom fights between the BeyHive and the Navy are further complicated by the defense of Rihanna or Beyoncé (when they are juxtaposed) because it is also a defense of their own investment in the fannish consumption of these singers.

[11] During an interview on Larry King Live (2009), Beyoncé said of Rihanna, "I'm here to support her, as well as all of my family. She's like family to me […] Jay and all of my family." Similarly, in the April 2016 issue of American Vogue, Rihanna noted that the rivalry is fabricated by the media: "They just get so excited to feast on something that's negative. Something that's competitive. Something that's, you know, a rivalry. And that's just not what I wake up to" (Aguirre 2016). Beyoncé and Rihanna's solidarity is a form of resistance to the processes that competitively pit their black femininities against each other, as Collins argues: "Self-defined and publicly expressed Black Women's love relationships, whether such relationships find sexual expression or not, constitute resistance. If members of the group on the bottom love one another and affirm one another's worth, then the entire system that assigns that group to the bottom becomes suspect" (2000, 170). Simply put, if fans engage in their juxtaposition, it counteracts this resistance.

[12] This is not to say that there are not instances of resistance by Beyoncé and Rihanna fans, which indeed need perusal. Still, this is an underdiscussed aspect of popular culture that needs further critical exploration, as it brings the whole MRWaSP societal agenda into question. Analyses of these constructed fandom fights, which pit black woman against each other and seek to reinforce stereotypes, illuminate wider societal complexities that greatly affect the practices of fandoms centered on women of color. Such cultural analysis raises further questions about the processes that actively work against black female solidarity and "harnesses the pleasures" and practices of their fandoms for the continuation of the dominant MRWaSP (Booth 2014, ¶2.11).