1. Introduction

[1.1] Sherlock Holmes has long inspired queer (note 1) readings and speculation as to the true nature of the friendship between Holmes and Dr. John Watson (Jarvis 2010; Mueller 2015; Redmond 2014; Redmond 1984; Robb 2004). The BBC's Sherlock (2010–) is no exception, and it especially lends itself to—arguably even encourages—such a reading, with its purposefully polysemous dialogue, normalization of gayness, lead actors' intense chemistry, and clever intertextuality, cinematography, and scoring. As prolific as the academic interest has been in the queerness of Sherlock, more so has been the fannish interest. Where academics are happy exploring the ambiguity of sexuality and relationships in Sherlock (Agane 2015; Botts 2016; Coppa 2012; Fathallah 2015; Graham and Garlen 2012; Greer 2014; Jencson 2016; Lavigne 2012; Mueller 2015; Valentine 2016; Waltonen 2015), fans are motivated to define them more explicitly; for example, the most popular interpretations see Sherlock as gay and John as bisexual, although readings explore a range of possibilities, from asexual and transgender identities for Sherlock to a heterosexual but homoromantic identity for John (note 2). Fans have shipped Sherlock and John—that is, made them an explicit romantic couple—since the first episode aired in 2010, mining the source text (what fans call canon) and creating vast outputs of fan fiction, fan art, fan vids, plot theories, and textual analysis in favor of the pairing known as Johnlock (note 3).

[1.2] The latter two, with the inclusion of fan vids that explore characterization, are generally called "meta." While the term meta has different concurrent meanings in fandom (https://fanlore.org/wiki/Meta), the usage here is a synonym for fan analysis, specifically analysis involving close readings of texts and the speculation and theories stemming from these interpretations (Newitz 2014). Academic studies of fans critically reading media, are, of course, nothing new. Interpretation is so fundamental as to be inseparable from other fan practices. Henry Jenkins defines fandom as "perhaps first and foremost, an institution of theory and criticism" whose attentive close readings put "academics to shame" (1992, 86). What fans now call "meta," scholars have previously called "talk," "discussion," "interpretation," "readings," and "analysis." For example, in her analysis of soap opera "talk" on the message board rec.arts.tv.soaps, Nancy Baym (2000) presumes all untagged posts to be interpretative by default, because users otherwise tagged their posts by function, which Baym groups, by contrast, as either social (tagged as "delurkings" or "tangents") or informative (tagged as "updates," "spoilers," "sightings," or "trivia") (note 4). Yet textual analysis as a transformative work often seems overshadowed by the creative work of fandom. While Louisa Stein and Kristina Busse list textual analysis among the fan texts that are the building blocks of interpretive communities, "theory and criticism" are signaled to be an unexpected genre: "fan texts, including fiction, art, music video, and even theory and criticism, create and contribute to the formation of interpretive communities" (2009, 197, emphasis added). Indeed, while their article summary mentions "analyses" as one of the fan texts created as a consequence of restrictions imposed by the interplay of source text, community culture, and technology, only creative fan texts (fan fic, fan art, and fan vids) are explored (192).

[1.3] What I would argue is new—or at least more prominent—is fans' awareness of meta as a distinct, named genre, with conventions both similar to academic textual analysis (the need to provide evidence and sources, in-group language, and stylistic rhetoric and norms) and different (informal language, heavily multimedia-based posts, high interactivity and communality, and postpublication peer review). Authors on Tumblr consciously tag their posts as "meta" (as opposed to the untagged interpretative posts on rec.art.tv.soaps), differentiating these posts from others tagged as "headcanon," "speculation," or "crack"; and fans submit their analyses to blogs devoted to meta, such as The Fan Meta Reader (https://thefanmetareader.org/). Meta's self-conscious visibility and fans' deliberate participation in critical dialogues with not only other fans but also with industry professionals warrants a closer look at the meta practices of specific fandoms. Further, I believe meta merits more attention for its creative and imaginative aspects, and deserves to be examined along with its fan fic and fan art kin for its subversive and transformative potential. BBC Sherlock meta is fruitful ground for exploration of this kind because the seeming disconnect between textual evidence for a Sherlock and John romance and stated authorial intent has produced a large body of analyses that both employ and reject authorial intent in the attempt to make meaning. What happens when the insight and creativity of the narratives generated by fans' meta outshines the actual canon in fans' eyes, and how is this engagement different than with fan fiction? When does meta go from being primarily analytic to creative, and how much is this influenced by professed showrunner (non)intent? The fact that fans want Johnlock meta to be seen as analytic, not creative, work—while either dismissing authorial intent in favor of the text itself or upholding it as harmonious with the text—is another example of Judith May Fathallah's "legitimization paradox," by which "legitimization and reevaluation of the Other—be it racial, sexual, or gendered—is enabled and enacted through the cultural capital of the White male" and "fan's writing is legitimated by the TV-auteur…Derivative writing that changes popular culture is legitimated and empowered—because and so far as the author says so" (2017, 9–10). While Fathallah applies this concept to fan fiction, she asks what other fan texts might "negotiate their reference to an authorized predecessor, and the points where, through deconstruction of that concept, they might compromise the paradox" (14). Johnlock meta, with its queer readings in spite of and/or because of the white male showrunners, exemplifies the tensions in this paradox and may challenge it to the degree to which meta is viewed as either challenging or affirming the author and source text.

[1.4] This paper theorizes the function of Johnlock meta in the Sherlock fandom, primarily written and distributed on the multimedia social blogging site Tumblr and secondarily used as evidence on Twitter for fans demanding both respect from media producers and positive LGBTQ+ representation in the media. As a disputed queer reading (note 5) of an open serial text, Johnlock meta's educational and legitimizing functions have provided new, enriched, and repeated textual evidence for the interpretation, reinforcing it in the face of doubt caused by others' denials of Sherlock's queer subtext and text. In advocating for a romantic reading of Sherlock and John's relationship, meta has served as a form of social activism, by both attempting to establish the queer reading as the preferred—but secret—reading (known as The Johnlock Conspiracy, or TJLC) intended by the creators and showrunners Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss and by resisting their extratextual heteronormative platonic stance on Sherlock and John's relationship. This contradiction of authorial intent/nonintent highlights the enduring tension in the Johnlock—and, indeed, in many other—interpretative communities, including academic disciplines, of where meaning lies between the author, the text, and the reader. This question is particularly pertinent to the production and reception of queerness, which Alexander Doty argues spans all three categories: He positions "queerness inside texts and production" and considers "queer reading practices as existing alongside straight ones," not as "alternative" (1993; 2000, 8). Michaela D. E. Meyer (2012) advocates that media scholars should "embrace nuances between text, audience, and production [author]…if we are to truly understand television's place as a communicative discourse in our increasingly globalized society" (265). This case study hopes to contribute to this endeavor in exploring the interplay and complexity of the entities of author/production, text, and reader in the Sherlock Johnlock fandom and beyond, especially given the international popularity of the show, the vocality of its most loyal fans, and the increasing demand for diverse representation in all media.

[1.5] Fans' appeals to the evidence of the text and its paratexts in favor of Johnlock, in contrast to the writer-producers' denials, has led them to create copious amounts of multimedia textual analysis and for some to use these analyses to support their claim that the show has queerbaited its audience; that is, teased its viewers with a same-sex relationship it never intended to actualize (Anselmo 2018, Brennan 2016; Collier 2015; Fathallah 2015; Mueller 2015; Ng 2017; Nordin 2015). Charges of queerbaiting serve both to grant interpretive authority to fans and to hold the authors accountable for an explanation of intent. Not all Johnlockers agree with the accusation of queerbaiting, however. Some appreciate the continued ambiguity and queerness of the show, which may or may not have ended with series 4, which aired in January 2017, but whose final montage effectively functions as a narrative coda for the series. These fans believe such accusations are premature, since there is talk of a fifth series, and/or believe that the show is queer in that it challenges traditional expectations of romance, relationships, identity politics—and even narrative—serving as a metacommentary on Sherlock Holmes adaptations. A subset of fans continue to believe that the creators still intend for canon Johnlock to occur, that series 4 is fake or deliberately bad and thus should not be read on a surface level, and that new content is forthcoming. Others disagree with the direct "fan-tagonistic" approach (Johnson 2007), accusing any of the show's vocal critics of "fan entitlement," "hate," or harassment of the creators whose creative autonomy should be respected, and of sowing discord within the fandom itself (Romano 2016). So, depending on the fan and the meta, the author is either dead, vilified, or deified—or sometimes, paradoxically, a combination of these.

[1.6] While many Johnlock fans would love to be declared the winners in this perceived interpretive game with—or war against—Moffat and Gatiss (and other fans), there is more at stake here than merely being right or wrong. Beyond the coveted prize of explicit and positive LGBTQ+ representation and the desire for a satisfying narrative are the spoils of legitimacy, of the acknowledgment—both by the showrunners and the general audience—of the possibility of being right, of presenting a valid reading. Armed with meta, Johnlock fans dispute caricatures of themselves as delusional fetishists co-opting gay relationships for their own desires or as ideologically driven social justice warriors demanding media representation, oppose extratextual authorial erasure of what is queer in the text, and contest the relegation of queer readings to fan fiction and fan spaces, vying for a share of authority in the arena of participatory interpretation.

2. The seductive appeal of analyzing Sherlock

[2.1] To begin, it is worth a look at why Sherlock invites such detailed and passionate analysis. First, Sherlock's long hiatuses between series (two to three years) and its short seasons (three episodes of ninety minutes each and one special episode) inspire deep and repeated analysis of a small amount of content. Repeated viewings release viewers from the grip of the plot and allow them to focus on the metatext of backstory and characterization (Jones 2002). With blank spaces within and between episodes, cliffhangers between seasons, and transtexts such as Sherlock's website and John's blog, the show exhibits a prominent feature of cult texts that Matt Hills terms hyperdiegesis: "the creation of a vast and detailed narrative space, only a fraction of which is ever directly seen or encountered within the text, but which nevertheless appears to operate according to the principles of internal logic and extension" (2002, 137). The desire to explore this narrative space and to preserve narrative continuity not only fuels the writing of fan fiction but meta as well. With its unanswered questions, offscreen happenings, seeming plot holes and time line inconsistencies, and deliberate ambiguity of character motivation, Sherlock is a prime example of a "drillable text" that "encourages a mode of forensic fandom that invites the viewer to dig deeper, probing beneath the surface to understand the complexity of a story and its telling" (Mittel 2013, ¶ 3; Mittel 2009).

[2.2] Second, the perception of quality from the show's BBC provenance (Evans 2012) and knowledge of the creators' other projects, such as Doctor Who (1963–89, 1996, 2005–) (Collier 2015), have helped to elevate the showrunners Moffat and Gatiss (whom fans dub "Mofftiss") to auteurs, which reinforces the notion that the show is worthy of analysis. While this conferring of auteurism is slippery for meaning making in television, given the variety of creative and production personnel involved with a show, it serves the purpose of giving fans a cohesive entity to either rally for or against when they argue for what is present in the text (Steiner 2015; Gray 2013). Lesley Goodman (2015) argues that "being a fan often means attributing disappointments to the failure of the creator, rather than accepting an incoherent or unsatisfying fictional universe" (671); similarly, R. M. Milner asserts that the fan's primary loyalty is to the text itself, not the organization that creates it (2009). In the case of Sherlock, this auteurism is especially fraught when the work of the creative team, whether it is the actors Benedict Cumberbatch (Sherlock) and Martin Freeman (John) (acting choices), the set designer Arwel Wyn Jones (suggestive or coded props), the composers Michael Price and David Arnold (musical themes), costume designer Sarah Arthur, or the various directors and directors of photography being brought to bear through meta against the stated intent of Moffat and Gatiss (note 6). For example, when in September 2017 supposed drafts of episodes were leaked online, fans pored over the draft of "The Sign of Three," written by Stephen Thompson, in an attempt to discern the extent, intent, and evolution of the gay jokes and subtext in the episode as compared to the final version, credited to Thompson, Moffat, and Gatiss. In Johnlock meta, all of the creative team fulfilling Foucault's "author-function" are opposed to "the organizing figure of an authorial personality," that of the "white male showrunner as the sole creative genius" promoted by the industry (Fathallah 2016, 461), at the same time that Moffat and Gatiss are lionized.

[2.3] This status of auteur is further complicated by fans' perception of the BBC's progressive agenda toward LGBTQ+ representation, fueled by fan discovery and analysis in 2014 of the 2010 BBC report, "Portrayal of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual People on the BBC" and its 2012 update (note 7). Sherlock was subsequently interpreted in light of this report, with some Johnlock fans believing that Moffat and Gatiss are beacons of change for queer representation to be lauded and supported, even if their actions of denial and fan ridicule are problematic. As Judith Fathallah notes, "Fans ascribe authority to figures whom they perceive as sharing their cultural politics" (2016, 476), while Stephen Donovan, Danuta Fjellestad, and Rolf Lundén raise the question of whether "in the era of identity politics…who the author is matters as much as (or perhaps more than) what the author writes" (2008, 14), with the author here being the showrunners and the BBC. The appeal of fan analysis in this context has been to uphold this hopeful vision of LGBTQ+ representation seemingly portended by various extratextual elements, such as Moffat's writing for Doctor Who (which is also simultaneously criticized for its portrayal of gender and sexuality), Gatiss's status as an openly gay man and advocate for LGBTQ+ rights, and BBC Worldwide's LinkedIn slogan of "Be part of making history: an unmissable experience" that featured an image of Sherlock. This notion of revolutionary media is a sentiment later echoed by actress Amanda Abbington's comments from San Diego Comic Con 2016 about series 4: "If we pull this off, it will make television history…It's kind of groundbreaking. They've done something again, these guys [Moffat and Gatiss], that's never been done before" (Tygiel 2016). Thus, in addition to the show itself, "the real world production of Sherlock [has been turned] into a text to be analyzed" (Collier 2015).

[2.4] Third, as a modern setting of Sherlock Holmes with creators who acknowledge referencing both Arthur Conan Doyle (ACD) canon and a variety of Holmes adaptations, the show is rife with intertextuality to be scrutinized in a way that escapes the staid Sherlockian tradition of privileging ACD canon, and allows younger fans to imagine Sherlock Holmes more freely (Polasek 2017; Polasek 2012). Moffat and Gatiss delight in their fanboy knowledge and transform their source texts in ways to showcase their creativity and originality while still claiming fidelity to ACD canon (Hills 2012b). Their claim of updating Holmes because "everybody's been getting [it] wrong, and we think we can get it right" prompts fans to ponder what exactly they are "correcting" in others' adaptations (Harris 2010): could it be the nature of the Holmes/Watson relationship? Fourth, and related to the last point, even though the showrunners characterize Sherlock as a "show about a detective" and not necessarily a "detective show" (Mellor 2014; King 2015), its content (such as the mystery of how Sherlock survived the fall from the roof of Bart's, which so preoccupied the fandom for two years that the writers parodied its theories in 3.01 "The Empty Hearse") and its transtexts (such as the Sherlock: The Network app game, which allows the player to solve a case with Sherlock), posit the viewer as a decoder of clues just like Sherlock, in a further example of Mittel's (2009, 2013) concept of "forensic fandom." As Matt Hills (2012b) astutely points out, Sherlock 1.3 "The Great Game" reinforces, via its plot, that there is indeed meaning to be found in media texts. The information needed to help solve the mystery is unconsciously gleaned from a variety of media sources, so that "every bit of apparent mediated background is actually the plot's foreground…The impression that's fostered is one of a media culture permeated with clues and vital knowledge" (31–32). Further, the "obsessed" fans in "The Empty Hearse" (TEH) are ultimately correct (Sherlock is alive) or provide a vital clue in the case (the train enthusiast who rewatches the footage on a loop realizes the train carriage is missing), again positioning the dedicated fan as a detective.

[2.5] Thus, Sherlock, by its content, format, and structure encourages close reading; and fan interpretation, "like academic criticism…involves the presumption of significance for any detail that can be perceived" (Allington 2007, 55). These details range from props seen on screen for a split second to wardrobe discontinuities to changes to the set. Are these in-jokes, continuity mistakes, clues, or red herrings? It is impossible to tell, and thus nothing is discounted (note 8). Possible clues even extend beyond the vast Sherlock Holmes universe itself to related media franchises, such as Doctor Who. CB Harvey (2012) illustrates how Sherlock and Doctor Who have long referenced each other not only through cultural allusions but also by shared production facilities and personnel: Moffat as showrunner and writer, Gatiss as writer and actor, and Joseph Lidster as author of transmedia tie-ins. Fans have noticed shared dialog between Sherlock and the Doctor, similar scenes, and mirrored characters—such as Vastra and Jenny, the married lesbian alien/human version of Holmes and Watson—reading one show onto the other in support for authorial intent for Johnlock.

[2.6] Fifth, and for many the most intriguing, is the show's focus on the relationship between Sherlock and John. Besides a tradition of queer readings of ACD canon and other Holmes adaptations, Sherlock possesses a "semiotic excess" that exemplifies, if not exceeds, the polysemy inherent in the televisual medium and necessary for television's wide appeal, employing all the main textual devices of polysemy in relation to Sherlock and John: irony, metaphor, jokes, contradiction, and excess (Fiske 1987; Fiske 1989). This excess, seen in the sustained deliberate ambiguity of Sherlock's sexuality, the assumption of gayness in the show's universe, the chemistry between the lead actors Cumberbatch and Freeman, and the sheer amount of queer subtext embodied in the dialogue, cinematography, scoring, and mise-en-scène, seems to tip the scale for many toward a queer dominant reading and away from the polyvalent (Condit 1989) platonic reading that comes from the commonly shared denotation that Sherlock and John love each other. The connotation of homosexuality "recruits[s] every signifier in the text…and excites the desire for proof" that will never be given textually (Miller 1991, 129): thus, the drive to analyze. The appeal of the show is indeed, as Moffat and Gatiss repeatedly state, not in the mystery of the episode (detective show) but in the interaction of the characters and the relationship between Sherlock and John (show about a detective), a distinction in genre that shapes the interpretation of the show by "influencing which meanings of a program are preferred by, or proffered to, which audiences" (Fiske 1987, 114). For example, after Mary Morstan/Watson was introduced in Series 3 and fans worried about the dynamic of their favorite dyad changing, Johnlock fans were both comforted and emboldened by Moffat's response to a question about minor characters' roles that assured them that "It's not a 'gang' show, it's the 'Sherlock and John' show. It's about developing their characters and their relationship, and the characters drawn into their orbit" (note 9).

[2.7] Thus, Sherlock possesses many of the characteristics of a cult television show that Sara Gwenllian Jones (2002) identifies: its "serial and segmented forms, its familiar formulae,…its metatextuality, its ubiquitous intertextuality and intratextuality, its extension across a variety of other media; its modes of self-reflexivity and constant play of interruption and excess" (84). Jones characterizes cult television as inherently queer in that the fantastic adventure of it must necessarily distance itself from mundane, normalizing heterosexuality. In this view, the practice of slash, the romantic pairing of same-sex characters, is not a resistant interpretive process but an interactive, immersive one that "renders explicit" cult TVs nonheterosexuality (90). Therefore, it is not surprising that Johnlock meta, in communally articulating evidence for the interpretation from the text, argues for the authors' intentionality of the reading, even if it requires decoding and explicating. The concept of meta in the Johnlock community has even taken on the connotation of revealing what is queer, as opposed to providing evidence for more obvious heteronormative interpretations, as seen in this Twitter exchange referencing meta written to support a romantic relationship between Sherlock and Molly Hooper (a pairing known as Sherlolly):

[2.8] @lidd_rose: When hetshippers try to write meta. Oh honey.

@BugCatcherinVF: heta

@MantleSkull: But…everything is already assumed straight. Whyfor this.

@BugCatcherinVF: So that you can assume straight even explicitly gay stuff. (November 16, 2017)

[2.9] Here, meta that posits a heterosexual relationship for Sherlock is seen to be not only redundant and unnecessary—given that heterosexuality is mainstream Western culture's default reading and hence needs no revelation—but also, paradoxically, to be a deliberate misreading of the queer text. The patronizing tone ("Oh honey") implies that the "hetshipper" is lacking in the "discursive or 'decoding' strategies available" to the queer decoders of Sherlock (Morley 1980, 173). Thus, these fans are aware that the dominant discourse of heteronormativity privileges certain readings of the text and recognize that different readers bring different knowledge and experience to the text, but they also claim that the text itself contains "explicitly gay stuff" that, contradictorily, needs to made explicit by meta. There is a tension here between the subtextual and subcultural properties of queerness "not obvious to heterocentrist straights" and what Doty argues is media texts' inherent queerness, part and parcel of "mainstream" culture that is accessible to everyone (1993, xiii; 2000). To these fans, Sherlolly meta seems, in Doty's words, "like desperate attempts to deny the queerness that is so clearly a part of mass culture," or in this particular case, Sherlock (1993, xii).

[2.10] This interaction of socially situated reader and text becomes even more complicated when we add in the question of authorial intent and certain Johnlockers' assertions that the queer reading is the preferred, but secret, reading of the text meant to be brought to light by analysis. Part of the appeal of analyzing Sherlock is belonging to the special group willing and able to tease out and articulate the nondominant meanings, whether or not one believes oneself the intended audience sanctioned by showrunners Moffat and Gatiss. John Fiske asserts that there is pleasure in the process of meaning making that surpasses that of the meaning made, a pleasure that results from "the production of meanings of the world and of self that are felt to serve the interests of the reader rather than those of the dominant" (1987, 19) and that only exists "in recognition that opposing semiotic forces are at work in the text" (1989, 71). In resisting heteronormative narratives for Sherlock and John and illuminating the same-sex romance suggested by the text, the largely young, female, queer, and neurodivergent composition of the Johnlock community (Anselmo 2018) is simultaneously asserting its power of (sub)cultural creation and semiotic decoding and declaring the legitimacy of its subordinate identities and interpretive strategies. For those Johnlock fans who believe their interpretation aligns with that of Moffat and Gatiss despite the creators' public repudiation of a romantic reading, the pleasure comes from claiming producerly authority, as many posts on TJLCer's blogs can attest to, with their exclamations of delight in authoring meta that solves the mystery of the show's intent and reveals the writers' consummate cleverness. As Diana W. Anselmo notes, these "girl fans" (note 10)

[2.11] muscle their way into a male-dominated canonical narrative, concurrently acting as unofficial decoders of the show's subtext and as official coauthors of dominant fan theories[,]…shifting their typical positioning as clueless mass consumers to knowing co-conspirators[,]…insert[ing] themselves into the inner sanctum of media production, a guarded elite traditionally inhabited by male executives, creative directors, actors, and screenwriters, the institutional structure largely behind Sherlock. (101, 105)

[2.12] The show itself even acknowledges the existence of these fans both explicitly, with the representation of fan theories and fan behaviors in "The Empty Hearse," and implicitly, with the secret cabal of wronged women in "The Abominable Bride" (2016), which some fans interpret as a nod to TJLC. ("We don't defeat them. We must certainly lose to them," Mycroft Holmes says; Mary Watson refers to "the heart of the conspiracy.") Whether the writers meant these examples lovingly or mockingly, fans see themselves as not just written into the text but an active part of it: an author, not as in creating original content or influencing the narrative, but as in illuminating the text for those who, in ACD Holmes's oft-quoted words, "see but…do not observe."

[2.13] This producerly authority and pleasure—held in tension with meta's dual goals of revealing showrunner intent and creative fan (co)authoring to save the integrity of the text from the showrunners, is collectively generated and amplified in significant ways through the writing and distribution of meta on the microblogging site Tumblr, whose structure enables easy reblogging of others' multimedia content and the ability to view the likes, comments, and reblogs of everyone who has nonlinearly interacted with the post. Johnlock meta is also the mechanism by which fans deal with their consternation with Sherlock canon and rage at the showrunners' dismissal of their queer readings. Before proceeding with a model of Johnlock meta that illustrates the tensions between author, text, and reader, followed by a deconstruction of a particular fan tweet accusing the showrunners of queerbaiting that perfectly illustrates the complex and contradictory relationship between Mofftiss, Johnlock fans, and the show, I will set the context more fully with a brief history of Johnlock meta.

3. A model of Johnlock meta

[3.1] After series 3 aired in January 2014, meta took on a new prominence in the Sherlock fandom, when many fans, citing copious textual and extratextual evidence, became convinced that Johnlock would become a canonical pairing—that is, explicit and official in the source text. Thus TJLC was born (see also Anselmo 2018; Christensen and Jensen 2018; Collier 2015; Paskin 2018). This was in contrast to the long-standing view, held by many since the show's inception, that the show was queerbaiting to attract and keep viewers. For example, the following mocking exchange between Ian Hallard, the actor-husband of Sherlock writer-actor Mark Gatiss, and actress Amanda Abbington, who plays John's wife Mary, was tweeted during the filming of 3.2 "The Sign of Three":

[3.2] Ian Hallard: OK, I get that some people like to fantasize about Sherlock & John as a couple but no one seriously thinks it will happen do they!?

Amanda Abbington: I do think it's funny how worked up people get about it…Why can't it just be friendship then? Isn't that more interesting to watch? (@IanHallard, @chimpsinsocks April 22, 2013)

[3.3] This conversation caused many (but not all) Johnlockers distress (note 11), especially since they knew that the episode would feature John and Mary's wedding and because the incredulity came from a gay person himself, married to one of the showrunners. However, once this episode aired, fans saw just how heavily laden with homoerotic and romantic subtext between Sherlock and John it—and the entirety of series 3—was, subsequently writing hundreds of metas about it, which makes Hallard and Abbington's words sound, to Johnlockers, not only cruel but disingenuous. The discrepancy between creator commentary such as this—repeated in paratexts such as interviews, Q&A panels, and DVD commentary tracks—and the show's actual content, has led some fans to conclude that the creators are lying to protect the plot of their slow-burn romance and to get heteronormative buy-in from a resisting audience. Hence the conspiracy component of TJLC, a term coined by Tumblr users graceebooks and joolabee in early January 2014 that quickly gained widespread currency.

[3.4] Backlash to the idea of canon Johnlock, not just from the creators but from other fans, spurred meticulous and lengthy close readings of the show and its paratexts, while also providing historical and intertextual context. Besides trying to convince others, Johnlock fans write for each other, reveling in what David Allington calls an "erotics of the barely perceptible" (2007, 58), uncovering and sharing layers of meaning and new details found through rewatching or making screencaps, animated gifs, or fan vids, reinforcing community through shared knowledge. Johnlock meta-ists' social activism of normalizing a gay interpretation even recruited new converts to queer readings of Sherlock and positively changed some fans' negative worldviews toward LGBTQ+ people and relationships. While Johnlock fans have varied in their degree of (non)identification with TJLC—either because of the divisive and reductive essentialist discourse and evangelistic speculation practiced by several of its vocal proponents that worked to suppress dissent over the diversity of queerness, and/or because of a lack of faith in Mofftiss and knowledge of industry conventions and restraints that might limit an explicit gay relationship—the belief in, or at least the desire for, Johnlock as narrative endgame has driven the majority of meta written by the fandom (note 12). TJLC meta has been advocating for and reaffirming the endgame point of view, which argues that the show's culmination in Johnlock is the only way in which the plot and character arcs make any narrative sense. Thus, close reading turned into a vocal predictive stance of where the show was going and, for some, where it needed to go, with such fans claiming not only authorial insight but prerogative: the text demands Johnlock. In the wake of Series 4, which aired in January 2017 and in which Sherlock and John are not shown to be in an explicit romantic relationship, Johnlockers of all persuasions—even those who have resisted a homonormative reading—have been trying to reconcile through meta their previous readings of the text with new canon. For those less invested in the endgame arguments, meta serves to illuminate all the queer parts of the text that lead to a romantic or gay reading, or as meta-ist tendergingergirl explains, her motivation has been "what else did they put in there?" (April 25, 2018).

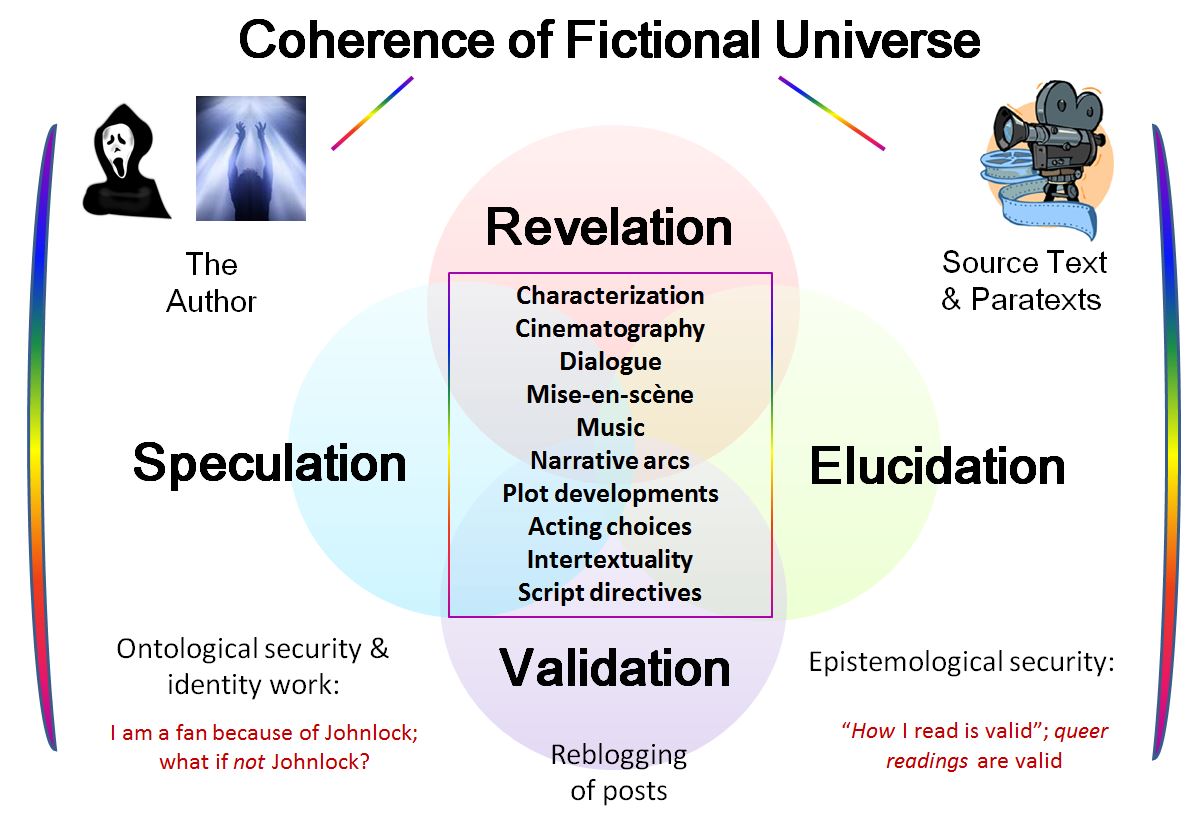

[3.5]. I propose that Johnlock meta functions in four non–mutually exclusive ways: revelation, elucidation, validation, and speculation. Revelatory meta exposes some hidden meaning or theme; elucidative meta clarifies or expands upon an already existing interpretation; validating meta reinforces another's reading with additional evidence or legitimizes the lens; and speculative meta makes narrative predictions. Meta takes as evidence various textual elements, such as characterization, cinematography, dialogue, mise-en-scène, music, narrative arcs, plot developments, acting choices, intertextuality, and script directives. As I will discuss further below, Johnlock meta also attempts to preserve the coherence of the fictional universe by attempting to reconcile the source text and its paratexts by either killing off or deifying the author, thereby providing fans with ontological and epistemological security in their reading of the show (figure 1). I consider meta broadly, including under the definition not only more traditional long-form text and/or multimedia analyses (text plus images/video/audio) but also shorter meme-like posts, from witty paraphrased snippets of dialogue that translate the connotations of the scene into denotation to photo sets and GIF sets (grouped still or animated screenshots, often with brief captions, with quotes from the text and its intertexts or paratexts). While these latter types of posts are usually not tagged as "meta" by their creators, they function as such, providing revelation, elucidation, and validation, even when fully multimediated with no explanatory text. Photo and GIF sets are visual shorthand, conveying richly layered meaning at a glance, immediately revealing dominant themes and parallel scenes, at least for those familiar enough with the canon and its referents to recognize and place them. For the initiated, a picture is indeed worth a thousand words. (While fan videos can be similar to photo and GIF sets in this respect, the added level of creativity of many fan vids makes a discussion of them outside the scope of this current essay, as do certain photo and GIF sets) (note 13).

Figure 1. A model of Johnlock meta, showing its functions of revelation, elucidation, validation, and speculation, while maintaining the coherence of the show's fictional universe by either killing off or deifying the author and appealing to the source text and paratexts to provide ontological and epistemological security. The overlapping circles of the Venn diagram illustrate the nonexclusivity and multiple functions a particular meta may serve, where the center components of characterization, cinematography, dialogue, mise-en-scène, music, narrative arcs, plot developments, acting choices, intertextuality, and script directives are variable. The placement of ontological security in the lower left quadrant suggests a stronger affinity with speculative and validating meta, while epistemological security in the lower right quadrant shows how it is especially influenced by elucidating and validating meta.

[3.6] For example, a popular photo set that circulated after the broadcast of 4.1 "The Six Thatchers" argues for its gay subtext by comparing certain scenes to those in Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), Moffat and Gatiss's favorite movie and an inspiration for their adaptation (figure 2). Gatiss describes Holmes in the film as being in "desperately unspoken" love with Watson (Morgan 2010), a statement Johnlock fans have long latched on to in support of their reading of Sherlock as gay—if not in the hope that Gatiss might make that love "desperately spoken" in the BBC version. The scene from The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, where Holmes pretends that Watson and he are a couple when being propositioned by Rogozhin to father Madame Petrova's baby and where "glass of tea" is being used as a euphemism for being gay, is compared to two separate scenes in "The Six Thatchers" (TST). The photo set comprising figure 2 clearly shows the parallel.

![Five color images, screenshots from The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, annotated with words. Top to bottom: image 1: [John Watson flirting with a woman via text]: This isn't a good idea. I'm not free. Image 2: [Holmes to Rogozhin]: You see, I'm not a free man. Image 3 (from Sherlock 4.1 'The Six Thatchers'): [Wiggins to Sherlock]: Is 'cup of tea'…code?. Image 4: [Rogozhin to Holmes]: You mean, you and Dr. Watson… Image 5: [continued] He…is your glass of tea? Bottom panel reads, 'FUCKING END ME WHAT IS THIS SHIT' with the following hashtags: #bbc sherlock #sherlock holmes #john watson #ftp #tst #tld #tplosh #tjlc #johnlock.](https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/download/1465/version/1557/1881/23063/figure-2.jpg)

Figure 2. Screenshot of photo set meta comparing scenes from The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes to Sherlock 4.1 "The Six Thatchers."

[3.7] This post by 7437locked, uploaded on January 20, 2017, almost three weeks after TST aired on January 1, was most certainly not the first to pick up on the connection between the two texts, but for fans who had not come across any previous meta linking these scenes, this would be a revelatory post. For those who had either made the connection themselves or previously read about it in another fan's meta, this post would serve as reinforcement of that reading. The creator's exclamatory comment "FUCKING END ME WHAT IS THIS SHIT" speaks to both the delight and exasperation of the Johnlock fan in encountering the blatant subtext on display here juxtaposed with Moffat and Gatiss's repeated denials of gayness, claims of their taking gay jokes too far, and fans reading into what is not there. This fan-made photo set, with its consciously chosen images for comparison, relevant quoted captions, and performative author commentary, is a valuable form of meta-ing, one that distills the essence of more traditionally text-based meta posts and complements them. Quickly comprehensible with key evidence and visually appealing to reblog, photo and GIF sets particularly serve to reveal and pique interest in new interpretations that can be explored in more detail in written meta and to validate (and delight in) an already existing and communally shared reading (note 14).

[3.8] Another important function of Johnlock meta is to sustain the integrity of the fictional universe—the logic of the storyworld that exists beyond a single episode. Cornel Sandvoss (2007) notes that fans have rigid expectations and wish to normalize the text and fix its meanings. Thus, the preponderance of meta takes a formalist and structuralist approach to the text, analyzing and theorizing character growth, plot consistency, and a satisfying, progressive narrative arc. For example, meta writer wellthengameover, going off of the fact that Moffat and Gatiss stated they had planned for five series of Sherlock, has written meta that fits the Johnlock and other character arcs and plot theories into a five-act structure. Fic author and meta writer marsdaydream posits that Johnlock-as-endgame theories exploded after series 3 aired in an attempt to reconcile Sherlock's childish, immature behavior with good storytelling: the interpretation that Sherlock is in love with John reads much better than him being an undeveloped manchild (Morimoto 2018). Meta writers have also reconciled the shift in episode structure and tone between series 2 (more case-based) and series 3 (primarily focused on relationships)—a change that put many fans off—as necessary for the relationship arc between Sherlock and John, with Mary being the romantic obstacle to be overcome. This argument has been extratextually augmented with creator statements that the relationship between Sherlock and John is indeed a "love story" (note 15).

[3.9] Leslie Goodman argues that fan desire for narrative coherence privileges the fictional universe "at the expense of the integrity of the creator(s) and the text itself": fans "chastise" the disappointing failure of an author by fixing the text through fan fiction (2015, 669). In contrast to fan fiction, however, Johnlock meta works to preserve the text by explaining how all the episodes' events relate, what they mean, and how they signify and, in the case of TJLC, redeem the authors, who are elevated to author-god status and are believed to have a progressive, divine intent: eventual explicit Johnlock. As Henry Jenkins explains, even resistant readers are reading inside the ideological framework of the show, and as "consummate negotiating readers, fan critics work to repair gaps or contradictions in the program ideology, to make it cohere into a whole that satisfies their needs for continuity and emotional realism" (2006, 111). An example of this kind of reconciliation would be meta that attempts to reconcile John's initial "it's all fine" attitude toward whatever Sherlock's sexuality is with his repeated and agitated "I'm not gay" assertions in later episodes, despite his earlier laissez-faire attitude and his intense dynamic with Sherlock.

[3.10] Like some fans' need for the assurance spoilers give, meta also provides ontological security, "the psychical attainment of basic trust in self-continuity and environmental continuity" that reduces anxiety (Hills 2012a, 113). Hence one of the appeals of speculative meta: for example, the plot developments and scenarios by which canon Johnlock could occur. While narrative consistency and coherence are necessary for ontological security, so are the ways fans identify with and relate to the text (Hills 2012a; Williams 2016) and to the producers (Morimoto 2018). For Johnlock fans, who are highly emotionally invested in the coupledom of Sherlock and John and who have incorporated their interpretation into their self-narrative and relationship to the show, denials by other fans and the creators threaten their sense of self. This might be expressed in the thought, "I am a fan of Sherlock because of Johnlock. What if there is no Johnlock?" Meta helps assuage this existential angst by providing evidence from the text against these denials and for when the text itself is perceived as failing to deliver, as in the case with the ending of series 4, where many Johnlockers experienced emotions ranging from mild disappointment to "'loveshock'…"the emotional trauma of falling out of love" (Williams 2016, 27). Morimoto notes that in the case of Sherlock "what may be at stake…is not (only) a desire for a canonical same-sex relationship, but confirmation that what fans see on screen, is, in fact, there" (2018, 267). David Allington further proffers that "what slash fans seek in their discussions…might be a grounding for slash consumption practices in the objective attributes of what is consumed" (2007, 49).

[3.11] Meta, rife with examples from the text, is the vehicle toward this objectivity, but fans' ontological security requires validation beyond the level of the text to that of the producers, who have consistently withheld such validation. While Moffat and Gatiss encourage fans to "have a great time extrapolating" Johnlock in fan fiction and on websites—that is, separate from the canon of the show—they deny it in their narrative: "There's nothing there" (Parker 2016). What fans object to, and what meta refutes, is the idea that Johnlock is a "meta-text"—"a tertiary, fan-made construction—a projection of the text's potential future, based on specific fan desires and interests" instead of being actual text or subtext (Johnson 2007, 286; Jenkins 1992). In other words, meta asserts that fans are not imagining a romantic relationship between Sherlock and John because they merely want to see it; they see it because it exists in the text. Or to put in another way, fans want to be seen as affirmational fans, bounded by and exploring the text as given by the author, instead of transformational, seen as manipulating the text to their own ends (Polasek 2012; obsession_inc 2009). In this way, meta wants to be seen ultimately as analytic, not creative, work, divining and championing textual, if not authorial, meaning. While meta writers' explanations and speculation for Johnlock might creatively differ, they are all anchored in the text, which they offer as ultimate evidence. Thus, the rhetorical move of TJLCers to make Johnlock an officially endorsed conspiracy is another method to control fan's ontological insecurity, as it gives the authors refuting their own text a logic and a purpose. Showrunner statements hold a hypnotic power and are of great interest to the meta community in the interpretation of Sherlock, even if the text is the primary vehicle of analysis—so much so that skulls-and-tea has for years curated and maintained on their Tumblr the Sherlock Creator Quotes Collection, which has archived pertinent intent- and characterization-related Sherlock cast and crew extratextual commentary on the show, gleaned from interviews, DVD commentaries, and panels. This has been an indispensable source to meta-ists for both discovering and fact-checking the provenance and context of attributed quotes as fans read the text with or against the creators.

[3.12] Relatedly, I further offer that meta also provides epistemological security by clearly outlining how it is queer readers know what they know and reassuring that how they interpret is valid, that queer readings are valid. The act of continually justifying an interpretation to a community that already shares the interpretation, what Allington calls "justificatory discourse," such as what happens on Tumblr when users reblog the same content over and over, performs group identity and promotes solidarity, as fans "periodically argu[e] away one another's doubts" (2007, 49–50). By both providing evidence for a Johnlock reading and modeling the process of interpretation—as revelatory, elucidating, and validating meta especially do—meta helps lessen the feeling that the writers are gaslighting viewers with their statements of "what you are seeing is not there" and provides Johnlockers with resources to counter resistance to the concept of Johnlock outside of the Tumblr community, such as on official and unofficial Sherlock forums and groups on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Reddit.

[3.13] I argue after Jonathan Gray (2010) that TJLC/Johnlock meta is a prominent paratext that has become an intrinsic part of the text itself. Acting much as spoilers do (Gray 2010), meta's function as unofficial paratext has kept the show alive for its most dedicated fans when it is off-air, which for Sherlock has been all but three weeks per two- or three-year period. Johnlock fans' meta is "queer cryptography," a form of unpaid and denigrated labor that is essential not only to their enjoyment, empowerment, and ontological security, but also to the show's profitability in a competitive market (Anselmo 2018). Further, it is almost impossible for newer fans to not come across a queer or TJLC reading of the show, whether they choose to ignore, deny, or agree with the interpretation. One fan, Rebekah, even started a YouTube video series called TJLC Explained, which over the course of the eleven months preceding series 4 compiled a variety of the previous two years' worth of TJLC meta into forty-eight easily accessible and digestible topical videos. As of January 31, 2018, over a year since series 4 aired, this channel still had 17,233 subscribers, with some of the videos having around 50,000 views each. Fan disappointment with no Johnlock was even parodied on the Hulu series Difficult People (2015–17) (note 16). Gray argues that with the "considerable power to amplify, reduce, erase, or add meaning, much of the textuality that exists in the world is paratext-driven" (2010, 46). Fan texts as such "open…up new paths of understanding" and "challenge the primacy of the show" itself as the locus of meaning because they "invite increased attention to a given plot, character, or mode of viewing" that might differ from industry-created paratexts (Gray 2010, 146–47). In the case of Sherlock, whose official paratexts send contradictory messages—for example, promo images and BBC social media accounts that are suggestive of Johnlock (figures 3 and 4) versus showrunner statements of denial—TJLC meta, as a unifying theory, seeks to reconcile them with the show itself (note 17).

Figure 3. Tumblr photo set meta featuring series 2 and 3 promo pics by abitnotgood. (January 20, 2017).

Figure 4. Tweet from @BBC3 during a rebroadcast of Sherlock 3.3 "His Last Vow" that comments on the opening scene. (December 18, 2015).

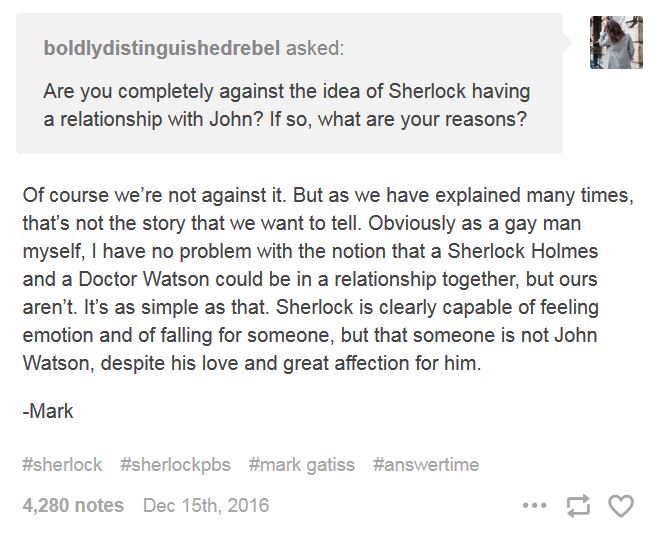

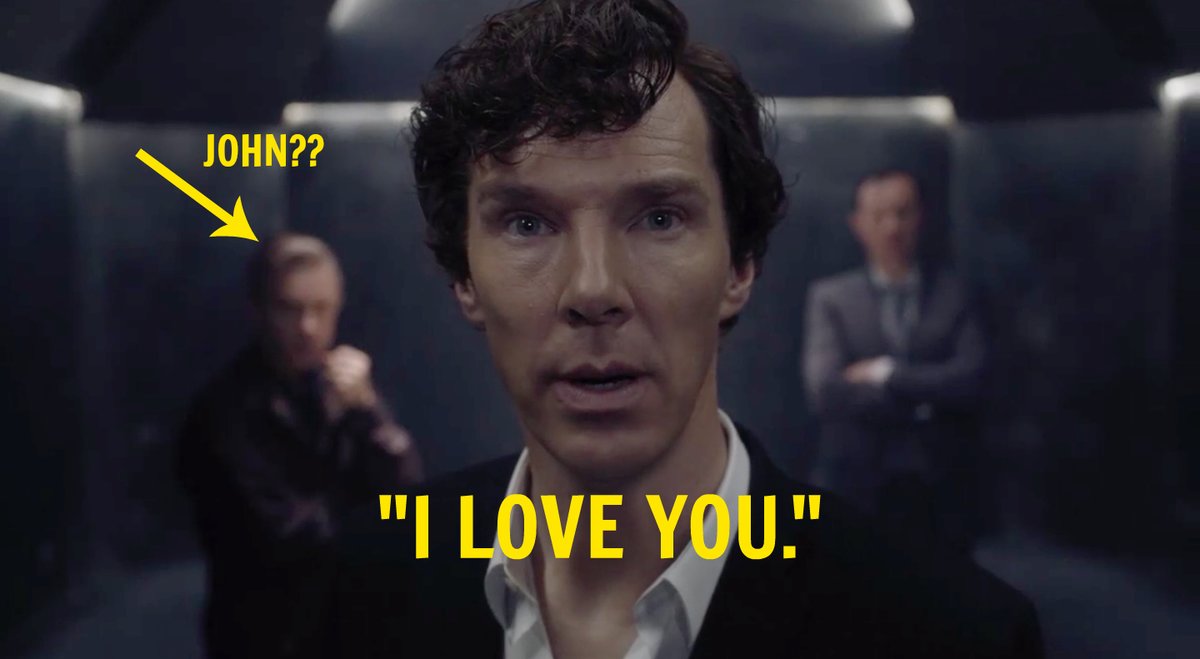

[3.14] The influence of TJLC/Johnlock meta has led fans to more directly interface with or influence the official paratexts that surround the show. For example, the showrunners and actors have had to repeatedly field questions about Sherlock and John's relationship by journalists in live and print interviews and by fans at panels and screenings. Despite showrunner denials of Johnlock—or any kind of love story—as late as summer and winter of 2016 (figure 5), promotion of Sherlock series 4 was highly self-conscious of it—with a BBC iPlayer tweet and trailer playing on the idea of Sherlock confessing his love (figures 6 and 7)—fueling disgruntled fans' vocal accusations on social media of queerbaiting, or worse, mocking fans, regardless of the actual input or influence either Moffat or Gatiss had with these publicity materials. An official video from January 11, 2017, on the Sherlock YouTube channel, where the host shares fan reactions to 4.2 "The Lying Detective" from social media (#SherlockReacts), even has the host pronouncing that the episode "really was dedicated to the greatest love story never told," a statement that both emboldened and then disheartened fans (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TLNT04MN1Ok). Assuredly the creators' awareness of Johnlock predictions and certain fan disappointment informed Gatiss's joking in the press that they had originally called one of the series 4 episodes "Backlash" (Fleming 2017). The creative team's continual engagement with Johnlock, whether by design or out of necessity, demonstrates the power of an interpretation fully rooted in the text; one, I argue, that is stronger than a similar argument explored through fan fiction, which creators can more easily sequester as mere fiction not worthy of serious discussion. Depending on one's point of view as to authorial intent, Moffat and Gatiss's refusal to discuss fan meta is either part of the conspiracy to protect plot points for series 5 or is an attempt to hold on to their exclusive rights as author. Either way, by dismissing evidence as jokes and insights as imaginings, the showrunners' denials have the effect of limiting or negatively shaping Johnlock meta's paratextual power.

Figure 5. Mark Gatiss's denial of Johnlock intent from the PBS-sponsored Q&A on Tumblr, December 15, 2016.

Figure 6. BBCiPlayer tweet, January 2, 2017, promoting series 4 and featuring the series 4 trailer.

Figure 7. Screenshot from the series 4 trailer, annotated with Sherlock's dialogue of "I love you" and tagging John with question marks, created for a preview article by Rachel Paige (https://hellogiggles.com/reviews-coverage/tv-shows/sherlock-love-trailer/).

[3.15] Even over a year after series 4 aired, the Johnlock paratext continues to exert its pull. Johnlock theories and the post–series 4 fan outcry of queerbaiting have captured the entertainment media's attention, but only to the continued detriment of fans, as articles and interviews appearing in March and April 2018 seem designed to stir up controversy by pitting creators against fans as an effective strategy for hits in the clickbait wars. This provocative but shallow coverage that never engages in questions of the text serves to further delegitimize a Johnlock reading and blame Johnlock shippers for the poor reception of series 4 and the uncertainty of a series 5. When asked about fan backlash to series 4 and fans expectations of a Sherlock and John romance, Freeman responded that Cumberbatch and himself have "literally never, never played a moment like lovers" (McLean 2018) and "never played anything as a couple, and that's just true…We play two friends who love each other. That's pretty different" (Horowitz 2018, 45:51). He states that fan pressures for the story to go a certain way are not fun, with "the…absolute insistence that Sherlock and John are a couple, should be a couple, have always been a couple" being the problem (Horowitz 2018, 45:35). While Johnlock fans might quibble with the semantics—Johnlock-as-endgame theories do not claim that Sherlock and John are currently a couple—the wording is less important than the strong message that these fans are wrong, and the pronouncement shuts down any exploration of why certain fans receive the show as they do, although Freeman gestures toward the obsessive close reader by contrasting fans to casual viewers who do not similarly engage. Moreover, a hard line is drawn between fan interpretations and the stated will of the creator. One interviewer, Josh Horowitz, comments that fans "almost create their own narratives," an idea which is fine with Freeman as long as the division is clear between fans "running with their own ball" in fan fiction and the authors writing their own show. A coupled Sherlock and John as found in fan fiction "doesn't happen to be the show we're making," Freeman pronounces (Horowitz 2018), even if in previous interviews he has been politely receptive to fan shipping—at least in fan art—claiming to participate in the activity himself, as he does during an interview on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert (December 10, 2016): "I've done some of them [explicit fan art]…I painted some of them." No mention is ever made of meta as a counterargument. Freeman not only clearly asserts authorial intent in his denials of canon Johnlock but also authorial control of the meaning, as he never once engages with the reasons that fans ship Sherlock and John, reasons that exist for the viewers in the text of the show itself.

[3.16] The problem with these interviews with creators is that questions of fan analysis, why fans believe as they do, are never broached, even though these interpretations are the basis for the compelling interview question. The intent of the author is assumed to be the last word on meaning and is never considered in relation to the text existing in its own right, open to reception. In addressing Johnlock, the discussion of interpretation is centered on fan fiction and creating one's own universe, not on analytic meta that would provide evidence for—and thus the legitimacy of—a romantic interpretation. Fans are automatically the lesser party—and the problem—in this scenario. In contrast, when asked his opinion on the matter of fan disappointment, Cumberbatch was more judicial in his response, stating that it is the storytellers' responsibility to manage fan disappointment and that "there are more people responsible [the creative team] than the people receiving what you're working on [the fans]," an answer that at least gives fans a bit of respect and discernment (Fullerton 2018).

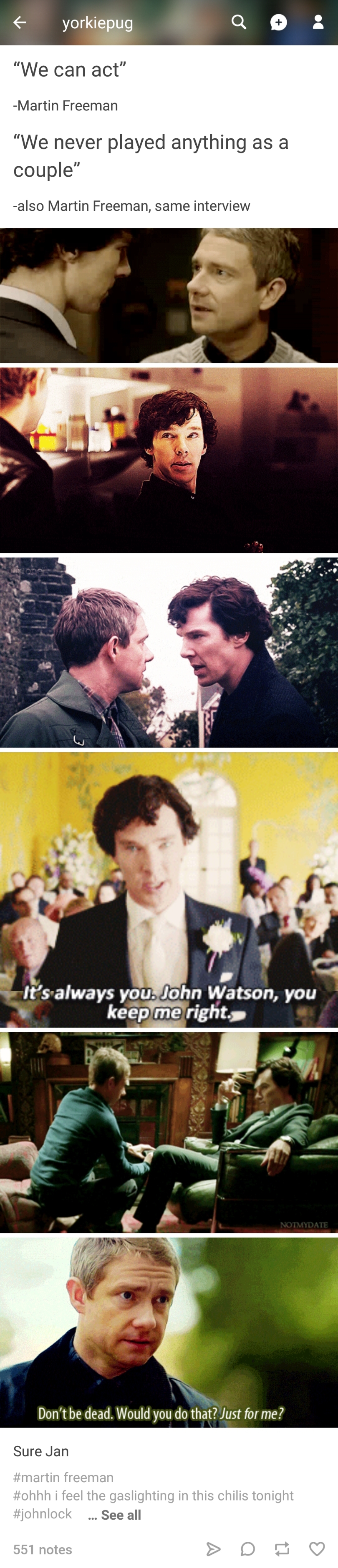

[3.17] The foregrounding of fan fiction and the lack of engagement with meta champions the authorial monopoly on interpretation, disempowers fans by relegating their labor to a separate creative sphere, and pits fans against each other—many fellow Sherlock fans follow the lead of the creators and unilaterally lambast TJLCers for their "cult-like" groupthink and "crazy demands," without seriously considering how the text may support their claims or acknowledging the range of fan beliefs. The media's implicit mocking of (predominantly female and queer) fans by never taking up their analytic cause reinforces not only the ways women are treated in media culture but also "the power relationships between the mass media and consumers" (Bennet, Chin, and Jones 2016, 115), which are then mirrored in factions of fandom. In the wake of Freeman's comments, Johnlock fans have reasserted the primacy of the text to refute his claims, as they do after every such pronouncement by The Powers That Be: "the show's the thing!" garkgatiss wrote in an antipress post (March 16, 2018), with the phrase again echoed by watsonshoneybee on a new post after Horowitz's podcast interview of Freeman (April 23, 2018). Validating meta abounded in the form of photo and GIF sets either preexisting or created for the purpose (figure 8), and even memes, such as this one by 221b-carefulwhatyouwishfor: "We never played a moment like lovers. / Yet our gazes were filled with longing. / Two 7-word stories" (March 16, 2018), a post that not only highlights Cumberbatch and Freeman's acting choices but evokes the fundamental decoding of "looks" as representing homoerotic desire (Woledge 2005). Yet even with such textual assertions—and the validating function of meta fully deployed—reassurance was fleeting, with a creator's words wielding the power to undermine one's interpretive confidence. Mrskolesouniverse acknowledged this feeling by tagging a post linking to the Freeman interview with "#I know that the only thing you should believe is the show itself #but I can't stop feeling [like a] stupid and delusional idiot after such interviews #why the fuck does it hurt so much" (April 24, 2018). The tension between the author, the text, and the viewer remains taut, especially with the Johnlock fan's assumption that if something is in the text, the creator intentionally put it there; or, conversely, with the creator's assertion that if something was not their intent, that element therefore is not in the text.

Figure 8. Screenshot of GIF set of six GIFs of Sherlock and/or John looking at or referencing the other, created by yorkiepug (May 1, 2018). The post is prefaced with "'We can act'/—Martin Freeman/'We never played anything as a couple'/—also Martin Freeman, same interview" and ends with a quip of incredulity in meme form, "Sure Jan." In her tags, yorkiepug mentions feeling gaslit.

4. Meta and the debate over queerbaiting

[4.1] In the wake of series 4, meta continues to assert the queer content of Sherlock, but to opposite ends, depending on how fans view the reliability and finality of the narrative and the intent of Moffat and Gatiss. Meta either provides support for fan accusations of queerbaiting, refuting Johnlock denials by extratextual authorial statements and new canon with evidence from new and old text, or it offers a strong rebuttal to those accusations by outlining how the text—and thus the showrunners—set up a Johnlock resolution for a possible series 5. Meta both aggravates and assuages the uncertain limbo with Sherlock. For the queerbaiting contingency, the amount of queer text and subtext in support of their claim both angers and legitimizes them; for the enduring TJLCers, the evidence in favor of their reading underscores not only their confidence in themselves but in the authors.

[4.2] The accusations of queerbaiting that had largely died (or been tamped) down with the advent of TJLC ignited again immediately after the airing of 4.3 "The Final Problem" (TFP), the last episode of series 4. Fans who were hoping for explicit canon Johnlock, such as a love declaration or a kiss, were frustrated by the continued use of ambiguity and subtext, as well as the foregrounding of heterosexuality, such as dead Mary Watson triangulating and then narrating Sherlock and John's relationship, while pronouncing "if I'm gone, I know what you could become"; Sherlock's pronouncing "I love you" not to John but to Molly, who has been in unrequited love with him; and callbacks to the lesbian Irene Adler, with whom John thinks Sherlock should pursue a relationship. While technically the ending is left open to interpretation and thus does not foreclose Johnlock, especially as there is the possibility of a fifth series, viewers perceive a shift in tone and a sense of finality of character arcs that suggest the evolution of Sherlock and John's relationship is done. These fans have cried queerbaiting for reasons of narrative disappointment as well as for lack of positive and explicit LGBTQ+ representation, complaining also about the queer-coded villains.

[4.3] Yet for many it is less the content of the show itself that has angered fans and more the official rhetoric of the showrunners denying the potential gayness or queerness of their own content, coupled with their adversarial and reductive view of Johnlock fans, that has certain Johnlockers crying queerbaiting. While some TJLCers may still discount Mofftiss's fan dismissals as part of a long con, others cannot accept their rude treatment of fans; even if canon Johnlock is in the future, the ends would never justify the means. For example, when fans took a quote about representation and gay characters that Moffat made regarding Doctor Who out of context and excitedly pronounced this as evidence for Johnlock, Moffat impatiently responded that fans were "taking a serious subject and trivializing it beyond endurance" (Parker 2016), basically equating fan desire for an explicitly gay Sherlock with slash fetishization, or the accusation that all Johnlockers want is to see two attractive men kissing. In this statement, Moffat not only dismisses the importance of LGBTQ+ representation for these fans, but also effectively ignores the difference between fans creatively shipping any characters in a text for fun and fans analytically shipping what the text suggests. When a young fan asked about the future for Sherlock and John after the BFI preairdate screening of TFP on January 12, 2017, attendees reported that Moffat dismissively told the fan to "go read the books," even though their adaptation itself departs from ACD canon. At the same event, Gatiss's curious phrasing of how he envisions a new series starting with "a knock at the door and Sherlock saying to John, 'Do you want to come out and play?'" (Tartaglione 2017; Dowell 2017) seemed to some fans to imply that at the end of TFP John is not living with Sherlock in 221B, a point that the show itself is open about, thus dashing Johnlockers' joy in the text's suggestion of cohabitation and its implications.

[4.4] In writing about the culture clash between "female, slash-centered interpretive culture and masculinist production culture" that characterizes the relationship between Johnlock fans and Moffat and Gatiss, Lori Morimoto states that "invalidation and even rejection by the official legitimate creators…can be intensely destabilizing, leaving fans with little recourse but to re-establish ontological equilibrium through the means at their disposal" (2018, 266–67). The recourse of choice for some Johnlockers/TJLCers has been to call out Mofftiss on their denials of same-sex love by tweeting rebuttals of evidence from the show, culled from meta, and by sending formal complaints of queerbaiting to the BBC. Fans organized under the name "Operation Norbury" (#Norbury), a clever Sherlock Holmes reference that tells the creators that they have become too arrogant (note 18). The BBC's heavy-handed response to these complaints, which Operation Norbury's recipients circulated through Tumblr and Twitter, incensed fans further: "Through four series and thirteen episodes, Sherlock and John have never shown any romantic or sexual interest in each other. Furthermore, whenever the creators of 'Sherlock' have been asked by fans if the relationship might develop in that direction, they have always made it clear that it would not." While fans do not dispute the latter statement of creator denials, they were outraged by the utter interpretative hubris of the former and rejected it, responding with counterevidence from the show with renewed fervor. Many fans felt as did @cupidford, who tweeted "You can't say you expect more from your viewers, and then disrespect and toss aside deep analysis from a majority queer audience #Norbury" (February 26, 2017). Many tweets that were part of the Twitter #BBCQueerbait campaign, such as those tweeted by Operation Norbury (@OpNorbury), posed presumably rhetorical questions such as, "Why did Irene (who is very good at reading people/knowing what they like) insist that John & Sherlock are a couple?" (June 16, 2017) and "Why didn't John respond after Irene states 'Well, I am [gay]. Look at us both'" (June 17, 2017), questions extensively elaborated on in fan meta. As meta writer mild-lunacy points out, as suggestive as such queer moments individually are, it is the cumulative effect of these moments in the text, either as funny or serious moments, that makes Mofftiss's joke explanations specious and where one feels the weight of authorial or narrative intent.

[4.5] These tweets and the evidence collected in meta pit the text against the showrunners' stated nonintent. Since the notion of queerbaiting hinges on authorial intent, what fans presume the producers' meanings and intentions to be (Nordin 2015) and what their actual intent is lies at the heart of the Sherlock queerbaiting debate. Those who take Moffat and Gatiss at their word that their show is not gay conclude that the showrunners have exploited queer coding and reception for their gain (queerbaiting), or the fans uphold the text as being implicitly queer (not queerbaiting); those that think they are lying advocate that the text is forthcomingly gay (not queerbaiting). There are heated opinions on both sides, both backed by textual analysis but differing about the legitimacy of author statements. Responding to fans who have asked TJLCers to be sensitive to those who feel hurt by Moffat and Gatiss, TJLC meta writer Amy (garkgatiss) responds, "Your feeling queerbaited is absolutely not ever going to ethically or morally compel me to stop telling you that you aren't being queerbaited" (April 27, 2018). Her certainty comes from her interpretation of the text.

[4.6] Either canon Johnlock will happen or it will not—what some TJLCers have binarized as the show being "gay or trash"—an essentializing reduction that privileges an explicit same-sex romance, one seemingly promised by the narrative, over the problematizing of binaries such as gay/straight, friendship/romance, and sex/love in which the show could also arguably be engaging. That is, fans accusing Sherlock of queerbaiting prefer explicit queer representation—Sherlock and John in an acknowledged gay relationship—over academic notions of queering (Sherlock and John in a romantic platonic, nonhomonormative, or undefined relationship) because in a heteronormative context everyone is assumed straight until proven otherwise and queer readings are seen as alternative (Nordin 2015; Doty 2000). If a same-sex relationship is not explicit, it effectively does not exist. Yet not all Johnlock meta argues for this explicitness, even if it presents evidence for a Sherlock and John romance. Those who use meta to oppose the queerbaiting charge point to nonessentializing queer moments of the text; for example, using the portrayal of Sherlock's positive relationship with Mary as suggestive of polyamory. However, what disgruntles fans in this case is not only the absence of a stated authorial agenda of binary-breaking, inclusive queerness but a reinforcement of and retrenchment in heteronormativity, in apparent conflict with the text.

[4.7] Further, queerbaiting also hinges on context—what Eve Ng (2017) calls "queer contextuality"—what fans can expect textually, intertextually, politically, and economically in matters of feasible canonical same-sex relationships. Many fans insist that in the 2010s, a gay romance need not be restricted to the subtext, rejecting the notion of play, creativity, and binary disruption—including that of producer/fan—that actualizing subtext in fan works (as opposed to in canon) allows in favor of much-needed and much-desired LGBTQ+ representation in the media (Brennan 2016). While subtext spawns engagement with the text in fan spaces or with the franchise, it cannot provide mainstream media visibility; hence, certain Johnlock fans' anger at the BBC in light of its commissioned LGB report and their need to speak back. Fans are not looking for creativity; they are looking for the validity and visibility that they feel the narrative has promised and for which they have evidence. For analytically inclined fans, the suggestion that fans go off into their separate fan spaces and create for themselves what the story fails to provide is infuriating and insulting. Johnlock meta writers view themselves as knowledge workers in service of the text (Milner 2009), not fantasizing fangirls.

[4.8] Emma Nordin (2015) offers producerly acknowledgement of fans' queer readings as an alternative, but not ideal, solution to queerbaiting, one that cannot ultimately represent LGBTQ+ identities but that can at least give viewers more interpretive legitimacy and social power. However, as of series 4, Sherlock fans do not even have this compromise available to them. While Gatiss has admitted to flirting with homoeroticism in Sherlock (Rouse 2010), both Moffat and Gatiss repudiate evidence of a Sherlock and John romance as jokes taken too far (but which they still continue to make through the series) and as fans reading into what is not there, claiming that in-text denials, such as Sherlock and John "needing two bedrooms" or John's declarations of "I'm not gay" settle the issue and outweigh any of the other myriad of textual instances and/or a greater whole. While critics might levy the fetishization charge at Johnlockers, Johnlockers fire back that queerbaiting exploits queer coding and receptivity at the expense of queer viewers, who remain hidden at worst or liminal at best in the shadow of the subtext. Further, Johnlockers reject Mofftiss's characterization of fan demands for queer representation as being issue-driven box ticking and thus necessarily artificial to the narrative. Instead, fans underscore that Gatiss's oft-repeated desire for characters' "incidental" gayness (Rouse 2010) is not only not antithetical to the developing relationship of Sherlock and John but also in support of the unlabeled slow-burn romance. In other words, fans' meta argues that actualization of Sherlock and John's romance is in line with the narrative that Moffat and Gatiss have constructed. It is good storytelling, not derailing identity politics.

[4.9] I would now like to deconstruct a rather rhetorically sophisticated tweet in the #Norbury campaign by @paddington2020 (February 5, 2017) that highlights the complex relationship between author, reader, and text in the encoding and decoding of Sherlock and the argument for Johnlock (figure 9). It constructs a hypothetical conversation between the complaining fans and Mofftiss, where in the still frame from the episode "The Abominable Bride" (TAB) used, Mofftiss are figured as the scolding John Watson and the viewers as the perceptive maid questioning his authority.

Figure 9. Tweet by @paddington2020 (February 5, 2017) referencing "The Abominable Bride" and encapsulating Johnlock fans' complicated relationship with showrunners Moffat and Gatiss and their text.

[4.10] This tweet not only uses the showrunners' words against them (the first line is a mashup of their responses to people who complain the show is too complicated to follow), but also the scene from the "The Abominable Bride" that is quoted as Mofftiss's dismissal of the very critical thinking they demand of their viewers is a scene steeped in subtext and intertextuality that suggests Johnlock romance. Most fans would have discovered the suggestive reference to and twist on the original ACD Holmes story through a Tumblr post, such as the following, which consists of an anonymous observation posted to Mazarin221b's blog and serves as revelatory meta:

[4.11] In The Problem of Thor Bridge (which I was re-reading for its canon train carriage knee-grope and gun-handling scene), the cook couldn't boil an egg properly because she was reading a "love romance." In TAB the maid couldn't boil an egg properly because she was reading a story about Holmes and Watson. I don't think I have to connect the dots for anyone, do I? (Tumblr, January 6, 2016)

[4.12] This scene is rife with other subtext as well—the maid who is effectively deducing the sorry state of the Watson marriage physically resembles Sherlock, for example—subtext explained in detail in various metas such as that by deducingbbcsherlock (Tumblr deactivated). The metas outlining the romantic tropes in the series are numerous, such as the one referenced here by ifyouhaveenoughnerve, which indeed lists 157 romantic tropes applied to Sherlock and John. But Mofftiss have shown that they do not want to seriously engage with fan interpretations—"Nobody asked you to be observant"—dismissing fans' Johnlock interpretations while simultaneously seeding their content with innuendo, hints, and references for those who can read them. Sharon Marie Ross (2008) prompts, "We should be exploring the ways in which online discussions of television shows may be prompting viewers—and writers and executives—to see the value of offering and attending to competing perspectives on issues ranging from identity and experience, to politics, to authenticity, to power, to how best to develop a character or plot." Johnlock fans have been vigorously, often contentiously, debating these issues among themselves through meta, taking the stand against charges that their claims are only ideologically driven (Romano 2016). But it appears that the showrunners see little to no value in "attending to competing perspectives" delineated in Johnlock meta, instead making blanket statements about fans "trivializing" issues and quarantining fans to fantasize in their own space. Some fans feel that Moffat and Gatiss purposefully wrote series 4 to stymie or defy the trajectory of the narrative—and thus analysis—as a power move for discursive dominance over fans in the cultural field (Johnson 2007; Williams 2010).

5. (Non)sense? Meta in a post-series 4 world

[5.1] Laurie Cubbinson writes this about fan fiction: "When the canon narrative heads in a direction that fans resist, fanfiction can be a method whereby fans come to accept that direction, or conversely, continue to resist it" (2012, 147). This characterization applies to meta as well, and it is particularly apt for describing post-series 4 Johnlock meta. Series 4 defied many fans' plot predictions and character readings, and the narrative structure and cinematographic choices have led fans to question the reliability of the narrative. With the series' concluding episode TFP, which challenged the suspension of disbelief for casual viewers and fans alike, many meta writers have been at a loss with how to proceed. While some Johnlock fans have been busy writing meta that struggles to make coherent sense of the totality of the Sherlock narrative, others despair over the futility of textual analysis in the first place, feeling that the showrunners have disregarded narrative expectations and "good writing" in favor of their own acknowledged "insane wish fulfillment" (Schnelbach and Lough 2016). Also, Mofftiss have admitted that what fans think of as clues are actually mistakes due to time and budget constraints, although these statements appear to be contradicted—or at least obfuscated—by Sherlock's creative team on Twitter and are cast in doubt by Mofftiss's reputation for lying (note 19). As marsdaydream laments in a Tumblr post called "Defying analysis: Sherlock S3–4":

[5.2] One of the things I'm struggling with, after S4, is whether or not it's actually worthwhile to approach the show analytically anymore…The problem lies in creating a show that deceptively behaves as if viewers should take it very seriously, when really the show doesn't seem to want that at all…Just because a character shows deep emotion on screen, doesn't mean that emotion always makes sense in a greater context. In S3 and S4…viewers picked up on plenty of these character-based inconsistencies and questions, and now we're all struggling to explain them. When really, the answer might be one big Occam's Razor: These things don't make sense, because they weren't written to make sense. Clear the screen, wipe the page, it was all a bit of fun. Deep analysis need not apply. (February 22, 2017)