1. Introduction

[1.1] It is a precondition for every study of fandom that fans are somehow different from other, usual media users and audience members. Otherwise the entire concept of fandom would become obsolete. Drawing on his research on 19th-century music lovers, Daniel Cavicchi (2007) writes about fans as those who refuse to accept anonymity and limited involvement of audiences and who want to extend their roles as members of audience toward more active participation and engagement. Generally, theories about fandom recognize and underline the impact fans make on their preferred medium: fans are, as has been extensively explored in the work of fandom researchers, active as users and members of audiences. Very often this activity is presented as a contribution of textual productivity.

[1.2] Emphasis on resistance and textual productivity among a group of audience members or users is, indeed, what is unique to fan studies in comparison to audience research in general. The tendency to concentrate on fan productivity is familiar, especially from first- and second-wave fan studies, where fan texts offered a tangible and perhaps easy basis for explorations into resistance and power relations in general (see Sandvoss 2005). These days, fandom is often discussed based on texts that are considered as an outcome of fannish activities (Hellekson and Busse 2006).

[1.3] Fans rework, cocreate, and recirculate texts that are possibly derivative and appropriative, or as Abigail Derecho (2006) suggests, archontic, in regard to the original content, as the texts seem to be ever expanding and never completely closed (for example, when fan fiction is written based on existing characters from a television series). For fan studies, Matt Hills argues, it is fans' creativity as producers that "has formed the basis for theorisations of fandom which celebrate this 'activity', whether it be video editing, costuming/impersonation…, folk songwriting and performing or fanzine production" (2002:39). While the mental production of meanings, interpretations, and identities has long been one of the interests of fan studies, the new and altered material forms of culture created by fans are arguably one of the biggest themes on which scholarly work, both on fandom in general and on games fandom in particular, has concentrated.

[1.4] Such critics find fan texts to be important markers of the creativity, rather than passivity, of fans. John Fiske (1992), for example, argues that all audiences produce their own meanings and pleasures around the products of the culture industries, but fans divert this semiotic productivity into some form of textual productivity. In the same spirit, Henry Jenkins (1992) has suggested five further levels of fan activity, one of which is the particular forms of cultural production and artwork (for example, fan writing).

[1.5] Also, in her brief history of media fandom, Francesca Coppa describes the development of "bigger, louder, less defined, and more exciting" fandom in the early years of the 21st century and states that "media fans are making more kinds of art than ever before" (2006:57). However, and this is what I will look at in this essay, the emergence of participatory cultures makes complex fans' active engagement where it takes a form of textual productivity. When participatory cultures are understood as cultures that have "relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one's creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices" (Jenkins et al. 2006:7), their characteristics seemingly overlap with the productive qualities of typical fan participation.

[1.6] Therefore, it becomes interesting to discuss if and how fan productivity is distinct from everyday media use that is inherently productive in current participatory cultures. For in computer games, "the authorial shift that occurs between gamers and designers differentiates it from other traditional media" (Jones 2006:266). Thus, games can be used as excellent examples of participatory cultures. In his recent study on game fandom, Robert Jones goes on to say that this shift "thus positions the video game as an important site of investigation into fan cultures" (2006:266), implying that looking at games could help us to deepen our notions of the relationship between fandom and productivity in general. Games, both as a medium and as a technology, engage their users in unique ways that result in multiple forms of coproductivity.

[1.7] Consequently, a crucial question for this essay is: when player productivity such as new graphical textures for game characters (known as skins) or other game modifications, which could be considered typical manifestations of participatory cultures, are understood as fan engagement, is that misreading them or charging them with importance and affect greater than what actually exists? Drawing a clear line between fandom and the productivity that is part of all game play is difficult and unnecessary. Instead, looking at different forms of productivity in games, which ultimately is the aim of this essay, helps identify the possible motivations for this productivity and can be used to categorize or examine the different groups of user-producers and their specific affiliations with specific games or characteristics of the same game. Until this work has been done, we can't concentrate on the personal affective relationships and identity construction of players and fans and recognize different modes of participation in game cultures.

[1.8] The "conventional logic [which has occurred in many theories of fandom], seeking to construct a sustainable opposition between the 'fan' and the 'consumer,' falsifies the fan's experience by positioning fan and consumer as separable cultural identities," states Matt Hills (2002:29). For him, fans are "always already" consumers. What I would like to add to this discussion with my essay, is the proposition that computer game players are, in addition to being consumers, always already producers. For this reason, computer games offer a good starting point for explorations on fandom and productivity.

[1.9] However, strikingly in game studies, games and play have broadly been conceptualized as non- or unproductive as opposed to everyday lives. Celia Pearce argues that unproductivity is a quality of games inherited from early play studies such as Huizinga's (1998) and Caillois's (2001) work that continues to inform some areas of game studies. Furthermore, such waste-of-time understanding of the use of media products is often characteristic of research on mass media as well (Pearce 2006). Pearce herself suggests that "in fact neither play nor games is inherently unproductive and furthermore, that the boundaries between play and production, between work and leisure, and between media consumption and media production are increasingly blurring" (2006:18). Works by Kücklich (2005), Sotamaa (2007), and Yee (2006) all discuss the intermingling of (productive) work and (unproductive) play qualities in game play engagement. In the same breath, Thomas Malaby proposes that three characteristics often associated with games, separable from everyday life, pleasurable, and finally safe—what he defines as nonproductivity—are not inherent features of games but "always cultural accomplishments specific to a given context" (2007:96). Without attaching the notion of unproductivity or, alternatively, productivity onto either play or games exclusively, this essay concentrates on the ways in which games do facilitate productive activities and discusses what forms of productivity already exist among players.

[1.10] This essay proposes a study of video game players that reveals the nuances of productivity within a specific culture, thus broadening our notions of player engagement and the ways it may overlap with fan engagement. Simultaneously, the essay aims to demonstrate that considering all game-related productive practices as fan practices is generally oversimplifying. Whereas current game studies seem to consider fandom predominantly linked to player-generated content—in other words, user coproductivity—my aim is to suggest that such accounts do not fully consider the motivations behind player engagement.

[1.11] I then want to propose that there are at least five kinds of productivity related to games, and that every one of them, in a particular way, stretches the dichotomy between fans and nonfans. The five dimensions I am going to introduce are: (1) game play as productivity; (2) productivity for play: instrumental productivity; (3) productivity beyond play: expressive productivity; (4) games as tools; and (5) productivity as a part of game play. These dimensions are not inseparable from each other but are used here in discrete ways to help unpack the complexity of the practices involved. When a game is played, these different forms and orientations behind productivity usually overlap and meet. Rather than offering a set of rigid categories, the dimensions suggested can be used as analytical tools.

[1.12] In regard to the format of this essay, I will start section 2 by proposing that all game play is a form of player productivity. The second dimension of productivity relates directly to playing and succeeding in a game (section 3), while the third grows from the expressive and artistic intentions of the player (section 4). In addition to these three I will discuss cases in which games serve as technical tools for forms of self-expression or other media fandoms that have very little to do with the game being played (section 5). Productivity as a part of play is introduced in section 6. It covers recent, so-called Game 3.0 games, which integrate the creation of new game content as a consumer product. Through suggesting these dimensions of game productivity, I intend to show that productivity in games serves different coproductive purposes than in other media fandoms and that these different productive practices all need to be discussed separately with regard to how they could be studied in terms of game play engagement as fandom.

2. Play as productivity

[2.1] It seems that the connection between media fans and original media producers is something that encapsulates computer game play already as a nonfan activity. Thus, it is important for the forthcoming discussion to understand the shared authority between designers and players of games as cultural products. Cocreativity, a term introduced to game studies by John Banks (2002) and further elaborated by Sue Morris (2003) and Jon Dovey and Helen Kennedy (2006), is a way to understand the ways in which authorship of a game is shared between paid game developers and the players of a game. In her study, Morris (2003) suggests first-person shooter games as products of collaborative creative processes between game developers used by game companies and individual players, because game modifications—player-made alterations to game content and mechanics—feed new ideas and content into professional game production. This results in a particular cocreative relationship between player and developers.

[2.2] Dovey and Kennedy (2006) broaden the concept of cocreativity to gather various forms of player productivity, such as fan art, mod arts, and tactical arts, and show its usability regarding explorations of games as cocreative media. Building on this work, I would like to suggest further categorization of such practices. First is to consider game play itself as player productivity.

[2.3] So I will start from the beginning—from the activity of playing a game—and I will follow other game scholars in proposing game play as productivity. Espen Aarseth's Cybertext (1997) paved the way to one of the foundational principles of game studies: games are texts with unique characteristics, cybertexts. Compared to linear and thus many older and earlier forms of media, such as television or film, computer games allow users not only to interpret, but also to explore, configure, and add content to them (Aarseth 1997). Games cannot be approached like linear media because they do not come into being until a player puts life into them, plays them, creates particular stories out of multiple possibilities, remixes her own set of actions and outcomes, and thus creates the media text while playing. This configurative practice means that games may develop in emergent ways and have unpredictable outcomes (for example, Aarseth 1997; Eskelinen 2001; Dovey and Kennedy 2006). Sal Humphreys has articulated this particularity of the medium, proposing that the game play "is an engagement which serves to create the text each time it is engaged" (2005:38). This feature has also had an impact on the study of games: "the computer game only exists as an 'object for contemplation' and analysis as and when it is played" (Dovey and Kennedy 2006:104). Productivity can, therefore, be understood as a precondition for the game as a cultural text.

[2.4] From this perspective, then, when playing computer games all players are producers of the original media text, meaning, again, that every gamer is a coauthor of the game, not only a producer of meanings of the game. And this idea seems to be agreed upon in game studies. Simply put, a user's involvement in the game text is significantly different from the contexts of earlier media. Aarseth's (1997) distinction between interpretative user function, where the user is only able to make decisions regarding the meaning of the text, and configurative user function, where the user can choose and create new strings of signs that exist in the text (note 1), sheds light on this change. The game player (co)produces the game throughout the play process itself, unlike the reader of a book or viewer of a film, for whom the material object already exists in the world as a product open for various interpretations by different users. The configurative user function required from the player can be illustrated with a simple but fundamental example. If a player does not make the effort of moving a character in a game—in The Sims 2 (2005), for example—no progress takes place and the game, depending on its dynamics, either stays static or faces its end quickly. Actions taken by the player have impact upon the functions available later in the game world and how game play can proceed. While Jones points out that "as an interactive medium, the video game requires the participation of the gamer," he reminds us that this interactivity should not be conflated with fan participation, such as the writing of slash fiction, and thus attempts to establish borders between fan and nonfan activities (2006:643). I agree with Jones that game play as productivity differs in degree from writing of fan fiction as productivity and try to go further in understanding where these differences originate.

[2.5] The partial authority every game offers to its player means not only that games are better understood as platforms for experiences than as products, but also that games as cybertexts are only partly predetermined or precoded before the activity of play takes place. In games, it is not only at the level of interpretation that the meaning of a game can be determined, but also as the material game artifact itself. However, each game as played can also be interpreted in various different ways once it has been created via game play, whereas in a narrative film the development of events and the order of them are prewritten in the text. The same boxed game may lead to many entirely different played games as developed by different players and when replayed by a player. Furthermore, every player can create a new and substantially different material game text every time she decides to play it.

[2.6] In multiplayer games, this means that the player also affects other players' experiences of the game. T. L. Taylor's (2006) and Humphrey's (2005) studies of MMORPGs (massive multiplayer online role-playing games) extensively describe the players' ongoing impact on each other's actions in such games. Their studies have opened up the social dynamics of multiplayer game play as well as the combination of unpaid and paid labor that produces such play. In World of Warcraft (WoW, 2004), which is one of the most popular contemporary games and an online multiplayer game with a player base of more than 11.5 million, players must at the very least create characters with specific qualities, wander around the game world with these characters, and then participate in temporarily creating a game environment for other players. They may kill opponents, pick up or buy items, and go into various locations and thus transform the game environment. Additionally, most players will take part in social or collective play, such as forming and attending parties (a group of players gathered together in order to accomplish a certain quest or other challenge in the game) and guilds, in order to participate in the social and in-game cultural system of WoW. All these activities change and create the game world for other players. As Humphreys writes, "the trajectory of game play is thus contingent upon the particular dynamics and action generated by shifting combinations of players" (2005:40).

[2.7] Therefore, configuration, the first step of player productivity, seems to be for a game what interpretation is for a film or a television series. To be explicit, a casual player is always productive, whereas a casual viewer is not. In games, interpretation is another level of user participation that comes after or parallel to configuration.

[2.8] Furthermore, in some games, configuration may encompass the systemic structures of a game. A player may, for example, be required to create her own goals for the game play, rather than simply responding to goals coded into the game system by its manufacturer. Especially in the case of so-called sandbox games—simulation games such as The Sims 2 that offer a form of free play without preferred goals or a winning state—the player must invent the aims of the game play. Configuration of the structure of the game is almost a precondition for this form of game. In The Sims 2, the player can decide to aim for a big house and large family, or to be a single person with a good career, or even aim to create a family with a graveyard for a backyard and ghosts coming in every night. These goals vary from player to player, though the game supports some goals better than others.

[2.9] The situation gets complicated, given that some games facilitate and afford more alternative playing styles. This means that players of such games can, through their game play and specific choices, create several different material versions of the game that have little to do with each other. For example, in WoW there are separate game servers for those players interested in role-play and for those concentrating on strategic skills and goals. The playing styles, ways of communicating with other players, and emphasis on different graphical, narrative, and mechanical features of the game are different depending on whether the player is interested in role-play or in strategy. Players who prefer role-play are likely to produce games with strong narratives and deep characters, whereas strategy-oriented players will focus on the structure and mechanics of the game as a rule system.

[2.10] Consequently, players with such differing orientations may also produce off-game texts that have different foci. The two orientations to be discussed in the next two sections seem to differ from each other drastically. One group of productivity (for example, machinima videos made of WoW game play) has stronger connections to earlier media fandom, while another, because of its instrumentality, is more strongly linked to game play and offers insights into entirely new forms of user productivity, and perhaps fandom. While this section described all game play as player productivity, the next two sections will look at these two forms of off-game productive activities.

3. Productivity for play: Instrumental productivity

[3.1] Another way productive participation in game cultures surpasses already well-studied forms of fandom is that some player-produced texts are simultaneously clearly part of the game play and materially separate; they are mainly written and organized outside the playing moment. Because computer game play often requires a lot of knowledge of the game, including techniques, strategies, and item locations, online sources offering this information may be used during the game play to assist the play, overcome difficult game situations, and generally play more effectively. As game play is temporally flexible and depends on the player, games enable the simultaneous consultation of this kind of instrumental information while playing—information on characters, objects, quests, and monsters in the game, for example. By instrumentality, I refer to tool-like use of information and means-to-ends rationality in order to gain efficiency in a game and especially with regard to the structures of the game and game mechanics. Such information is provided on Web sites designed for this purpose. Seth Giddings's characterization of walkthroughs describes both their value for players and their instrumentality:

[3.2] It is in part an instruction manual, assisting a stuck video game player through a particular puzzle, tortuous labyrinth or fiendish demand on hand-eye co-ordination, but it is also a verbal map of the peculiar space–time of the video game's virtual world. It is a document of the writer/player's skill and effort in exploring and solving every last aspect of the game world. It is knowledge shared via the Web to both assist other players and to display the writer's expertise in, and devotion to, the game in question. A walkthrough is a determinedly non-literary work, dispassionate, stripped of non-instrumental description and of most subjective reflection on its writer's part. (Giddings 2006:31)

[3.3] Sources such as walkthroughs and databases are often continuously updated or rewritten by people while they play the games. This characteristic of computer game-related productivity derives from the combination of the technology used for getting involved with the original text, a game, and the transition of fandoms to the Internet. Consequently, often involvement with both the original source text and the productive practices related to it take place on a personal computer and often also online. This has noteworthy implications for game play, as the player is able to participate in fan productivity and community interaction in parallel with the play itself (note 2). Information on the game is easily available online and moving between the game and sources available online is smooth. Players who would rather find optimal solutions and models of acting for game-specific challenges than learn them slowly by trial and error can easily consult online sources during the game play.

[3.4] The terms power gamer and hard-core gamer are usually used when there is an emphasis on a player's efficiency, clear personal goals, and desire to win. Such players invest plenty of time and money in play and often have a playing style that does not meet the usual expectations of fun or leisure, even though they themselves may "consider their own play style quite reasonable, rational, and pleasurable" (Taylor 2006:72). In connection with these player types, Taylor (2006) discusses instrumental play, in which such power gamers are situated more closely to work than play in their approach. "The simple idea of 'fun' is turned on its head by examples of engagement that rest on efficiency, (often painful) learning, rote and boring tasks, heavy doses of responsibility, and intensity of focus" (Taylor 2006:88). This contrasts with the average person's idea of game play as something purely enjoyable. Correspondingly, with instrumental productivity I refer to the way introduced player productivity yields new and altered game texts that offer tools for more effective play. Because of their functional status, these texts do not usually serve any other purposes outside game play, meaning that they are not interesting for nonplayers as independent texts. (But some can be. For example, there are walkthroughs that are closer to interesting stories than to instructions on how to proceed in a game.)

[3.5] According to Andrew Burn (2006), authors of walkthroughs know the procedural demands of the game system and are not interested in a holistic view of the game, which includes the narrative, for example. The aim of a player is to proceed through the game as efficiently as possible. The texts that I group under this notion of instrumental productivity are based on the player's interest in games as systems and structures. Use of such sources does not necessarily lead to certain interpretations of the game but will impact upon players' choices and actions. These choices and actions, once made, form a game open to interpretation. As an example, a WoW player may search an online database for the average selling price for an herb she has picked up from a distant land. She may sell it at a small discount in the in-game auction house because she needs the money urgently. When another player buys the herb in order to create a potion needed in fighting, the seller gets her money via the in-game mail system. When these transactions and events have taken place, interpretations about the economic ideologies, workings of the auction house, and fairness of players in setting up prices can be made.

[3.6] Another example of instrumental productivity is online databases such as Thottbot. Thottbot is an unofficial WoW database that features tools for players to use to obtain game-related information about game items, locations, quests, and monsters. The database is equipped with a search function, which makes it very convenient to use alongside the actual WoW game. Figure 1 shows some of the information available for a player interested in the statistics, looks, sources, and uses for a specific item. Using Thottbot to find locations for quests or certain monsters frees the player from spending time on what, from some perspectives, may seem unimportant or routine tasks. For many players, databases such as Thottbot, as well as add-ons providing the same information, are extremely important for game play. The game is played with one or more different databases open in the browser windows, and a play session involves continuous switching between the game and these databases. Players who use such databases increase their chances of success in the game as they have more information about the system and simulation available. Such functional practices are used by players because they make playing easier, efficient, and, in the end, more fun.

Figure 1. Information on WoW character's equipment, magister's robes, on Thottbot. [View larger image.]

[3.7] Interface modifications and add-ons could also be understood in terms of instrumental productivity. While it is the players' responsibility to search, transfer, and transform the information from walkthroughs and databases into the game and finally toward actions and decisions in the game, interface modifications and add-ons are player-made pieces of software that change the looks and functions of the game interface and are thus materially parts of the game. They are available online for other players to use and serve the same function of facilitating more effective game play (note 3). These modifications, which are popular among hard-core players, offer information and tools, new buttons and other interface elements, for executing certain actions that would normally involve performing additional crucial clicks that take seconds to carry out or for browsing sources outside the game. For example, the QuestHelper add-on for WoW tells the player how to finish a quest in the easiest and fastest manner. Meanwhile, the Auctioneer Suite offers statistical information on sellable game items so that selling and buying them via in-game auction house in WoW is faster and more profitable.

[3.8] Moving to the economical and political aspects of such additions to games, the making of player-originated elements of games is often supported by game companies, as they offer tools and distribution platforms for making and sharing them. The communities that are formed through these practices are then enlisted into commercially successful networks and companies such as Maxis, the development company behind The Sims, which take full advantage of this free content made by players (Banks 2002). Instrumental productivity does indeed sometimes take the shape of commercially profitable engagement. The economic point of view with regard to player-produced texts is nowadays made even more complex by third-party companies that make a profit based on player productivity but are not directly associated with game publishers. Mia Consalvo (2007) describes how one of the databases, Allakhazam.com, originally "a one-page guide for EverQuest" and now an information source for all major MMORPG games, is offering content that has been added and updated by player communities. This is provided for its premium users for a yearly fee of $29.99. Another form of such paratextual industry is, Consalvo suggests, game-guide publishing. Strategy guides such as World of Warcraft Strategy Collection 2008 (BradyGames 2007) and game-world map books such as World of Warcraft Atlas, Second Edition (BradyGames 2008) are available in mainstream book stores and offer firsthand information and glossy pictures on WoW. Unexplored areas of the game can be studied in advance from the atlas books, for example.

4. Productivity beyond play: Expressive productivity

[4.1] We can distinguish game modifications from play as productivity because the way a game is altered through modification results in changes to games that are visible to other players and affect their game play. Borrowing Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman's term, Jones (2006) calls this kind of play transformative play. To illustrate the same difference between play as productivity and interface modifications, for example, we can look at Aarseth's (1997) useful distinction between scriptonic and textonic changes to a cybertext, although we risk stretching the concepts to excess. Scriptonic change refers to modification in the information as it appears to players, while textonic means changes in the cybertext itself. Joost Raessens (2005) talks about the same phenomenon, but uses the word construction in referring to additions to a game as software. It is a more extreme form of productive participation and is characteristic only of a minority of players because it requires advanced technical tools and skills from the player. Interface modifications are examples of instrumental productivity that produces textonic changes.

[4.2] But there exists another group of game modifications, also resulting in such changes, that does not indicate instrumentality by definition. These game modifications are probably more widely known and add new content into the game worlds in terms of game levels or objects or changing the looks of the characters—their skins. Skinning is the practice in which players use graphics editors or special software designed for this purpose to alter the looks of game characters. This can vary from changing the color of a character's skirt to creating an entirely new character with a new skin color and clothes. Accordingly, a skin is a player-made outlook for a computer game character or avatar. Making a skin involves using a graphics editor to create a new picture and saving the image file in a specific place in the folder where the actual game has been installed.

[4.3] Making such alterations to the game serves no purpose in more effective game play but is rather a practice of self-expression and creative exploration. Players of The Sims 2 are well known for their active skin production. Players have created skins that, for example, bring cultural symbols into the game (figures 2 and 3). These examples further demonstrate that self-expression can also make a game to better suit local values and tastes. Helen Kennedy (2005) has studied women players who use skinning in order to enrich the range of female characters in games that contain only limited representations of females, such as the Quake games (1996–2007). Her examples show that there sometimes seems to be a political importance to skinning, even if the agenda behind it is not explicitly political.

Figure 2. Burqa skin by bettye from ModTheSims2. [View larger image.]

Figure 3. Bindi skins by TwoHorses from ModTheSims2. [View larger image.]

[4.4] While there seems to be no instrumental aspect to the modifications that affect the visual characteristics of the game world, such as skins (note 4), such modifications are often understood as a form of hacking and are thus seen as resistant toward the original game. But, just as Jenkins (2006) observes that it is overreaching to label all DIY media as a form of destructive cultural jamming, it is not sufficient to understand game modifying as simply countercultural. Makers of game modifications do indeed rework and partly destroy the games they modify but often do it in order to lengthen their engagement with the game and to offer their insights of the game to other gamers. This said, however, projects such as Velvet Strike, an antiwar game modification inserting politically charged graffiti into the game world for Counter Strike (1999) can be seen as a kind of tactical art, because, as Dovey and Kennedy (2006) argue, there is an intended political or activist impulse behind such modifying. Game-world modifications are, of course, generally regarded as copyright infringements. They are also made with player-created tools or even with no tools at all and therefore require good technical skills and more effort than that for production integrated into the game itself.

[4.5] Because game modifications can appear both to embrace the original text and to be seemingly countercultural, I wish to discuss them generally as an expressive form of game productivity together with machinima videos (videos created from 3D game play footage recorded during the game), stories about games, drawings, screen captures, and poems based on games. These practices do not support play or exist as essential parts of a game, but some of them, such as machinimas, are created during play. They can also exist as independent texts with no need for the user/viewer/reader to understand the original game. For example, several humorous machinima videos are equally understandable and thus entertaining for both players and nonplayers. At first sight, it also seems that this model of player productivity covers what is traditionally considered fan production: that is, fan fiction and drawings, as well as movies and videos based on the original text. Machinimas, for example, are often pure game play movies or involve inventing stories about the lives of game characters.

[4.6] But creating fiction with game characters is somewhat distinct from making fan fiction representing existing movie or TV characters, which is a practice widely maintained by TV fans. The difference emerges because game characters' life histories and characteristics are only partly encoded in the game and, depending on the game in question, can be defined to some extent by player actions. The same character can thus represent entirely opposite roles, values, and identities in different players' games as well as in the fan fiction based on these games. Such a character is not as fixed by its qualities as a character attached to linear media. For example, The Sims 2 does not suggest personal histories or specific characteristics for game characters outside a player's choice. A The Sims-based machinima video titled "Leet Str33t" makes fun of geeky language and topical Internet phenomena, presenting characters that live their ordinary lives on Leet Str33t communicating in leet (or, correctly,1337) speak (note 5). Meanwhile, many other games offer characters with detailed characteristics and colorful backgrounds with which to create further stories and machinima. For example, the players of Super Mario games have created tens of machinima videos representing the love lives, dinner plans, and other everyday occasions of the game characters Mario, Luigi, and Princess Peach. Finally, in MMORPGs such as WoW, it is the player who creates the character and its life history little by little during the play by choosing how to proceed in the game, how to communicate with other characters, what to wear, and what kind of tasks to fulfill. Similarly to The Sims games, the characters are thus freely adjustable to narratives of any kind.

[4.7] While I am defining instrumental productivity as the contribution of players who have a strong interest in game mechanics and structures, it is visual representations, characters, and narrative that seem to be the starting points for what I call expressive productivity. These texts are created to serve the artistic self-expression of a player (or a nonplayer, as I will later suggest), and the motivation behind creating them may well be anything from fondness for a particular game lore or character to distributing political statements. The distinction leads toward separating productivity that concentrates on form/structure from productivity around content in games.

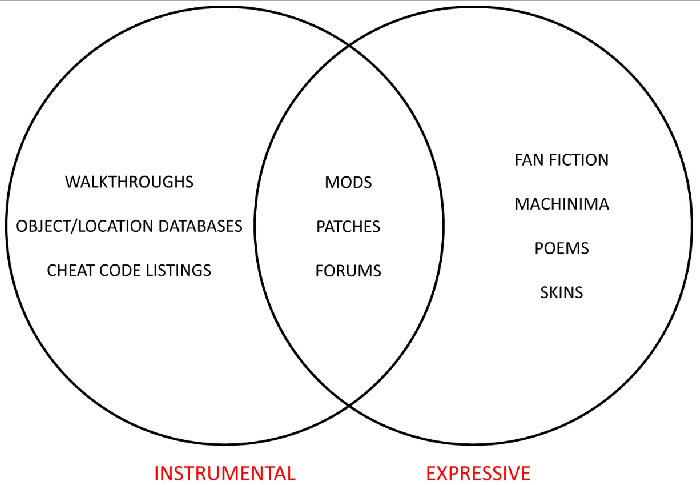

[4.8] If we then compare players who create poems or stories based on games to the players writing walkthroughs and strategy guides, one helpful point of comparative duality could be to look at MMORPGs. In these, role-players are often distinguished from power gamers, and this position is supported by Taylor's (2006) research on EverQuest (1999), which shows that role-players, players who play the game in-character and attempt to identify with it, are normally seen as interested in the backstory and narrative, while power gamers, players who aim to play as effectively as possible, concentrate on goals, such as completing game quests. In other words, role-players seem expressively productive and power gamers instrumentally productive. Figure 4 classifies different game-related texts according to their origins in either expressive or instrumental productivity.

Figure 4. Different orientations of game-related productivity. [View larger image.]

[4.9] Finally, while game modifications and other player productivity that encompasses reworking of game content cannot be understood as purely countercultural or resistant, the motivation for making game modifications may derive from a wish to continue one's experiences with a particular game even longer and in new ways. Such productivity actually extends the life cycle of a product and creates deeper engagement with the game. Jenkins (2006) and Julian Kücklich (2005), among others, have suggested that such participation creates passionate affiliation and brand loyalty. Player production results in what Charles Leadbeater (2008) has noted about participatory cultures in general: players can get products that are exactly as they wish them to be and customized for their very own purposes. While some game scholars (for example, Kücklich) wish to suggest that game developers gain a one-sided advantage at the expense of players, Humphreys reminds us that industry and players are not mutually exclusive spheres: "The interests of commerce and the interests of culture are not necessarily opposed" (2005:47). However, when concentrating on active player-engagement, there is often a risk of idealizing and imposing too much empowerment onto these actions.

5. Games as tools

[5.1] My presumption of dividing productivity that is not part of game play into the suggested two categories is not without problems. Quite often machinima videos, game-fact forums, and walkthroughs all present an expressive account of the narrative, simultaneously suggesting more effective ways to play the game or presenting important details of the game. The duality could also be contested by the fact that games are also used as tools for other purposes than playing or even for purposes related to other fandoms. Henry Lowood suggests that "when a computer game is released today, it is as much a set of design tools as a finished product" (2006:29). Machinima videos are an excellent example here. Lowood offers an introduction to games' tool use in machinima making: "Machinima makers have learned how to re-deploy this sophisticated software for making movies, relying on their mastery of the games and game software. Beginning as players, they found that they could transform themselves into actors, directors and even 'cameras' to make these animated movies inexpensively on the same personal computers used to frag monsters and friends in DOOM or Quake" (2006:26).

[5.2] Player-made music videos form one of the genres of machinima. Often, as soon as a new music video for a pop song, for example, is released, a machinima version of it can be found on the Web. This means that a player has used a game in order to reconstruct the video with the video game technology. The player has chosen characters and character outfits that correspond to those in the original video. Then, like a puppet master, she has organized the characters' movements so that they resemble what happens in the original video. Finally, the player has used software in order to record what happens in the game.

Video 1. A machinima imitation of Lily Allen's music video for "Alfie" by Badboy2008.

Video 2. Original Lily Allen music video for "Alfie."

[5.3] Louisa Ellen Stein's study (2006) of players of The Sims games serves as another kind of example of games' tool use. The players she has studied created Sims characters from the Harry Potter books and then devised new fannish stories within the game with these Sims characters. Stein suggests that the unpredictability of The Sims games creates a feeling of the characters' full existence in the game. Fans feel able to act outside the limitations offered by the canon of Harry Potter because the characters seem to exist "beyond the original source text, and beyond even the specific captured narrative being told through Sims images" (Stein 2006:257). Character qualities introduced in the books do not apply to the game, and Sims Harry Potter characters act independently of them.

[5.4] Several questions arise from such hybrid productivity and games' tool use. Do these examples suggest that a music video made with The Sims 2 playing "Alfie" by Lily Allen that loosely copies the original music video is a Lily Allen fan text? Or is it a The Sims 2 fan text? Or is it both? How to approach an episode of Lost made with The Sims 2? Or an episode of Friends made with the same game, or a Brad Pitt skin for a Sims character? Are the Harry Potter fans discussed in Stein's study also fans of The Sims? Whatever the answer is, it is clear that games can be mobilized to express fondness for a song or particular star, to create new stories, express opinions, or even advertise a product, as the Coca-Cola machinima advertisement made with Grand Theft Auto and CBS's Second Life machinima advertisement for Two and a Half Men demonstrate. Furthermore, hundreds of autonomous machinima series and short movies exist, such as the five seasons of a well-known machinima series, Red vs. Blue (2003–2009) by Rooster Teeth Productions. Red vs. Blue is a parody of first-person shooter games, a comic science fiction machinima made using visuals from the Halo games (2001–2009), and it features two opposing teams in futuristic desert settings.

6. Productivity as a part of play

[6.1] James Newman ends his book Playing with Videogames (2008) with a short discussion of the third generation of video games, generally described by the umbrella term Game 3.0 (note 6). These integrate player cocreativity into the game play itself (finessed by the industry as "putting the spotlight back onto the consumer") and are clearly connected to the social software made available by Web 2.0, such as YouTube and Flickr. Newman uses Little Big Planet (LBP, 2008) as an example of Game 3.0, but Spore (2008) and Hello Kitty Online (HKO, forthcoming) fall into this category as well (note 7). The first two games were published in the UK in late 2008, Spore (PC and Mac) on September 5 and LBP (PS3) on November 5. While introducing these games, I will show how productivity is increasingly being integrated into game play as one of the central mechanics of the game, although it is still not always necessary for game play. Such productivity also seems important for the continued success of games to a changing industry. In the marketing of the games discussed hereafter, the making of players' own content has been forcefully introduced and such content has been then used in order to attract greater numbers of players.

[6.2] Spore is characterized as a multigenre massive single-player online metaverse video game. Whereas the notion of massive(ly) multiplayer game refers to games with a large number of simultaneous players, it is not clear what is meant by massive single-player games. I suggest it is precisely this that is interesting and novel about this particular game: a new way of mobilizing a large number of players and generating collaboration without actually bringing them into the same game play situation to play with and against each other. In Spore, this is implemented by the technically nondemanding production and sharing of player-generated content, such as Spore creatures. A number of editors are made available for the players to create their own content for the game, the most significant of which, Spore Creature Creator, had already been published by Electronic Arts before the actual Spore game appeared. Several features are included to facilitate including other players' creations into one's own game, such as an RSS feed for favorite creator content. Significantly, the favorite creator is "just" another player of the game. Furthermore, Web sites such as The Best Spore Creature (http://www.bestsporecreature.com) already include millions of creatures created by players (note 8).

[6.3] While the marketing material for Spore utilizes the catch phrase "Create, Play and Share," another game, the action platform game LBP, proposes three surprisingly similar themes and modes for the game: play, create, and share. Similarly to Spore, the LBP player is able to add material made by her or other players into the game and editors for such work are integrated in the game product. These include characters and levels, for example. In numbers, players had shared 84,000 levels for the game by November 13 (Three Speech 2008). The HKO game, which will be a franchise-led MMORPG for the PC, differs very little from many other popular MMORPGs but presumably has a very different target audience. Unlike earlier games in the genre, HKO offers an in-game blogging tool as well as a tool for taking real-time footage from the game play, a new form for player productivity. The game's Web site also includes a number of ways for players to produce videos, and even the beta testers for the game were initially selected by videos created by potential players. Productivity in HKO does not cover the making of new parts for the game and for other players to play, as do Spore and LBP, but it still brings traditional play more toward player productivity.

[6.4] As these three examples show, out-game player productivity is an inseparable part of such games, not an add-on or extra. But this is a new level of player productivity, one that works in addition to play itself as a form of textual productivity. In Game 3.0 games such as Spore, LBP, and maybe also HKO, the production and dissemination of the player-made game texts is anticipated by the producers and developers and is an important aspect of marketing the games in a way that leads to the creation of a community within which distribution and share of new game content takes place. Productivity in these games serves as a strong starting point for creating player communities, since player creations are not limited within one's own game. A special relationship with the game is not a requirement of player productivity in these cases; instead, player productivity is built into the game itself.

7. Conclusions and future reflections

[7.1] Alongside game play, the WoW player may chat online to her friends, endlessly develop character(s), and play the game, thus making the game look and feel different to other players. She may contribute to Thottbot by describing where to look for a specific rare mob, take part in raids in order to kill new bosses, express her opinions regarding the price of items in the Allakhazam.com database, or write a game ticket to a game master in order to report a bug in the game. If scholars define fandom on the grounds of the degree of contribution to the knowledge about a game, then most of the MMORPG players would be categorized as fans. This would unnecessarily stretch the concept of fandom. Instead, it seems that what has earlier been considered as fan productivity is increasingly being structured into the media text itself in games.

[7.2] In this essay I have suggested that productivity in games is manifold and encompasses all players. Although fan communities and community interaction have not been the primary foci of this essay, the importance of other players and online communities for player productivity is probably clear from the dimensions of player productivity I have suggested. Places for sharing and distributing player-produced content facilitate player communities, and player-produced texts such as character skins or walkthroughs become evaluated and discussed within these communities. Peer recognition is an evident motivation for players to produce new content. Thus, not only does cocreativity encompass a player and an official producer, but players are also coproducers in regard to each other. This coproductivity is collaboratively orchestrated mainly on online forums. Furthermore, it is a unique aspect of multiplayer games that communities among the users/audiences are already created during game play. These communities form strong bases for fan communities. A player of a multiplayer game such as WoW may be involved in community interaction both in-game and outside of it on an online forum, yet parallel to game play. Player communities are acting simultaneously in multiple places, and they are interconnected and overlapping. As competition between game publishers is hard, these communities also form and maintain strong opinions on competing products and therefore have impact upon the sales of the games.

[7.3] As player productivity or cocreativity grows from a group of varying motivations and is tightly linked to the production of games as media texts, I therefore suggest that we need better definitions for game fandom as well as for its different forms (note 9). Not all the productivity related to games can easily be understood as fandom. In game cultures in particular, as suggested in this essay, there are forms of productive activity—such as the creation of walkthroughs, game modifications, and add-ons, as well as the possibility to easily share content created in-game among the player community—that do not have counterparts in the fan activities of traditional media. However, it is already easy to recognize that various forms of recent media use, including what has been called Web 2.0, require more specific and elaborate accounts in media fandom. Understanding the underlying motivations and connections to original media in such productivity can be entered through the levels of productivity presented in this paper.

[7.4] This essay may seem to suggest, too, that computer game players' productive practices are especially emancipatory. However, even the games I have used as examples show that instead of independent DIY culture, game cultures remain very dependent on a mass market, and the most visible fan texts are altered from or based on those popular games. It is also worth noting that in the end, only a small percentage of all the players contribute to the production of new texts. While the highly productive power gamers may appear to occupy the most extreme position of a cocreator, even they work within the varying economic and legal boundaries and regulations set by global corporations.

[7.5] Examples used in this essay are all from PC games and primarily from the games WoW and The Sims 2. Therefore, in addition to exploring more closely the social, political, and economic aspects of the different dimensions of player productivity, applications of the proposed model to different forms of games, game genres, and playing styles are what I would suggest as starting points for future research. Such work would result in enriching and broadening the proposed categorization and in multifaceted comprehension of player productivity.

8. Acknowledgments

[8.1] An earlier version of this paper was presented at the DiGRA 2007 (Digital Games Research Association): Situated Play conference in Tokyo. Thanks go to Olli Leino for reading and commenting on drafts of this essay. I would like to give a special thanks to my supervisors, Estella Tincknell and Seth Giddings, and advisor, Helen Kennedy, for their valuable help with the composition and arguments of this essay.