1. Introduction

[1.1] Over the course of eighteen days in 2014, 55 million internet users visited popular video game streaming site Twitch.tv to view or participate in a gaming experiment called Twitch Plays Pokémon (TPP). The idea was simple: broadcast an emulated version of the popular game Pokémon Red Version (1998) played not by a single user but by anyone who logged in to watch. By entering commands into the game's chat feature, the viewers could control the onscreen character, but with hundreds of thousands of viewers entering commands at once, the experience quickly got out of hand. Though Pokémon Red is, by design, a straightforward story about a ten-year-old monster trainer who defeats eight gym leaders to win a regional competition, members of the TPP community invented interpretive fictions to mythologize their experience's twists and turns—attributing causality to the randomness of their collective actions and reimagining the game's goals—until the simple game became a cosmic tale of anarchy versus democracy featuring an impossible Christ figure, a false prophet, a computer that demands the blood of the innocent, and an inanimate object that turns out to be God incarnate.

[1.2] In this article, I analyze TPP as a unique but illustrative anecdote about participatory media fandom that demonstrates how rhetoric is connected to the constitution, adaptation, and continuation of fan discourses. While previous scholarship suggests that fans use rhetorical strategies to argue for and make sense of their experiences (note 1), I expand these claims by theorizing the structuring relationship between this rhetoric and fan discourse. According to Henry Jenkins, argumentation becomes officially engrained with community knowledge-production practices through a set of community-defined rhetorical procedures (Jenkins 2008, 33–39). The study of these rhetorical procedures provides helpful insight into how a community is thinking about its own development. As Virginia Kuhn argues, studying rhetoric is more than an avenue for determining what kind of speech is persuasive in a fan community. It also allows fan theorists to engage "the specificity of the discourse communities from which they arise" (2012). Taking Kuhn's claim as my point of departure, I argue that because rhetorical forms are dependent on certain styles of reasoning and speaking, they afford and constrain possibilities for the permutation of community-interpretive fictions. These rhetorical forms are not immutable, but their entrenchment in existing community practices and shared repertoires means they are inextricably interwoven with existing stylistic, affective, mediated, and playful elements of fan discourses. As such, studying rhetorical form can help fan studies understand the factors that lead fans to develop particular collective interpretations of their experiences.

[1.3] In this article, I perform a rhetorical analysis of TPP fan art and subreddit conversation. Choosing from popular examples shared on TPP's subreddit, I focus on a subset of fan art that appropriates the generic conventions of medieval Christian and ancient Egyptian artwork. I have chosen to do so because these two art styles appear frequently in TPP fan art and because they reflect the neoreligious speaking styles common in much of the fan discourse across this subreddit. In particular, I closely analyze three works that received significant attention on the subreddit: Frickerdoodle's Days 1–7 (2014), Aeuma's The Massacre of Bloody Sunday (2014), and Whoaconstrictor's The Origin of Ancient Helixism (2014). I argue that these styles, which arise after the traumatic loss of a game character, help narrativize the use of two oppositional sacrificial anecdotes—first of Christian martyrdom and later of sacrificial offering—to make sense of in-game loss and nonagential game mechanics. Overall, my goal is to follow the tropological development of sacrifice as a guiding term within the TPP mythology and to center the importance of rhetorical strategies in this development. This is particularly important for the study of networked game fandoms, such as TPP, because it helps us read across participation, production, and discussion to analyze the frameworks that fans use to explore their experiences.

[1.4] This article is divided into three major parts. I first develop my claim that rhetorical criticism can help us to better understand fan discourse. Second, I introduce the TPP fandom's relationship to its mythology by analyzing their use of the medieval Christian art style. Here, I argue that the community appropriates practices of moral-spatial arrangement popular to medieval Christian altarpieces to set the conditions of possibility for envisioning the story's struggle as a Christian corollary. My emphasis here is less on which characters are good or evil than on the structuring work of arrangement as a rhetorical form, its allowances and constraints. Third, to demonstrate the importance of rhetorical form, I follow a later transition in the community's perspective on sacrifice away from the Christian martyrdom narrative and toward a more brutal position on the necessity of sacrifice to hungry gods. Studying subreddit arguments about later work that uses mock ancient Egyptian art styles, I suggest that this transition is connected with this new style's common rhetorical forms, particularly anthropomorphic mysticism and sequential storytelling. Thereafter, I conclude by considering possibilities for rhetorical criticism in digital fandoms organized around intensely variable yet collectively experienced fannish objects, such as TPP and other networked games.

2. Rhetoric and fan discourse

[2.1] Aristotle famously defines rhetoric as "the available means of persuasion" (2007, 35). This definition has been both the bane and boon of rhetorical criticism. Oftentimes, scholarship operating under this definition focuses heavily on the word persuasion and simplifies the study of rhetoric to the study of persuasive effect. While I do view rhetorical speech as persuasive, symbolic action intended to affect the mindset of its audience, rhetoric has a crucial secondary element that is central to this study. Enacting constraints and constructing rhetorical appeals require that the speaker adapt her ways of speaking to fit the audience and occasion. As explained by Kenneth Burke, "you persuade a man only insofar as you can talk his language by speech, gesture…attitude, idea, identifying your ways with his" (1969, 55). It is Burke's conception of rhetoric that forms the framework for my analysis. When we reframe our speech to persuade, we accept things about what the audience believes and incorporate those beliefs into our speeches; doing so structures the ways in which speech happens. Thus, in the study of "the available means of persuasion," my emphasis is on availability. The study of rhetoric is not simply a study of the ways in which we change minds but also a means of understanding action grounded in existing community practices. When looking at the rhetorical practices of fan art and conversations, I am less interested in whether a speech act successfully persuades community members than I am in how the drive to be persuasive affects how the speech act was made. What does the acceptance of existing forms allow the fan to say? What types of speech does it delimit? How might styles of speaking affect the possibilities for later speech?

[2.2] As a method, rhetorical criticism focuses closely on speech acts. This refers not only to texts themselves but also to speakers, audiences, their surroundings, and their interrelationships. Similar to literary criticism, rhetorical criticism often centers texts and draws conclusions from the various strategies and devices used by those texts, but in doing so, the critic must always read these strategies through the lens of the speech act. The question is thus never simply "why does this appeal work?" It is instead "why does this appeal fit the purpose of this text?" Or "why does this appeal resonate with this audience?" Or "why did the speaker use this appeal rather than some other?" It is this last question that forms the foundation for my own analysis. I am chiefly interested in how fandoms develop a collective speaking style and how that style informs the permutation of fan fictions and discourse. To theorize this, I focus most closely on rhetorical forms, recognizable and recurring speech arrangements that structure what is said in particular ways. While I study two genres of TPP artwork, medieval Christian and ancient Egyptian, it is the rhetorical forms commonly invoked in these art styles—spatial-moral arrangement, sequential storytelling, and anthropomorphic mysticism—that inform my actual claims about the affordances and constraints of TPP discourse.

[2.3] The analysis of rhetorical form provides a helpful expansion to our understanding of fan discourse. As Stuart Hall describes them, discourses are "ways of referring to or constructing knowledge about a particular topic of practice: a cluster (or formation) of ideas, images, and practices, which provide ways of talking about forms of knowledge and conduct associated with a particular topic, social activity, or institutional site in society" (1997, 4). Discourse and rhetoric are inseparable; if discourse is the collection of ways of thinking and speaking about a topic, rhetoric here refers to attempts to participate in this discourse, to use these ways of speaking to get something done, whether that be persuading an audience to act or conveying an attachment to a fannish object. Thus, to analyze rhetorical form in fan discourses is to study how discursive tendencies and possibilities are mobilized for persuasive effect and how attempts to do so are grounded in existing preconceptions and material conditions. While this has many benefits for the study of fan discourse, it is particularly helpful for theorizing a determinate (but not causal) explanation for fan discourse development. New forms that resonate with the community's experience of an event allow new discursive possibilities to flourish, but they also afford and constrain the development of new relationships and fictions because they structure the ways in which fans think and talk about their experiences. Other methods, such as discourse analysis, are helpful for mapping out the multiplicity of fan ideas and can oftentimes help us to make similar statements about how fans respond to meaningful happenings around the fannish object. However, especially when fan discourse becomes multilayered because the community is attempting to establish a new narrative canon, operating with cultish or parodic reflexivity, or attempting to cope with the new mechanics of a networked game world (all of which apply to TPP), fan studies needs a strategy for reading these experiences into fan texts themselves. This is not to say that rhetorical criticism should replace discourse analysis in these environments, only that it helps us to account for varying degrees of fan situatedness.

[2.4] In this article, I analyze some of the rhetorical forms common to TPP artwork. I track these forms as commonly reproduced appropriations of the same artistic style, which, though not necessarily causally related to one another, are indicative of the permutation of rhetorical form in TPP's discursive space. As Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites suggest of image appropriation, "the study of image appropriations is one way to study what people do with images, and particularly as they use them to make a public statement. It gauges reception by observing how it is converted into production" (2017, 301). The same standard goes for the appropriation of rhetorical forms; we see that fans have inspired artistic and rhetorical styles that are repeated. The purposes of these appropriations need not be boiled down to pure persuasive purpose; they need not even be conscious, though I'd venture they usually are. Even when fans are using their artwork to express attachments without investigating them, the fact that such expressions are reflections on previous engagement with the fan community and fannish object means that their engagement is already discursively structured in some way. Again, the goal is not to express causality but to see rhetorical form as indicative of a style of thinking. The arrangement of these works is both a trace and an act.

[2.5] I envision this study as an addendum to scholarship on digital fan-sharing practices that has adopted Lewis Hyde's "gift economy," in which gift-giving is seen as a vital not-quite-marketplace kind of exchange that both literally establishes and symbolically represents community relationships. As Karen Hellekson describes this process, "writer and reader create a shared dialogue that results in a feedback loop of gift exchange, whereby the gift of artwork or text is repetitively exchanged for the gift of reaction, which is itself exchanged, with the goal of creating and maintaining social solidarity" (2009, 115–16). This active upkeep of community status is also the process by which a communal discourse develops. The gifts and responses "are incorporated into a multivocal dialogue that creates a metatext, the continual composition of which creates a community" (115). This community ethos is particularly important on digital message boards in which conversation is often structured around the event of gift exchange and subsequent discussion. Rhetorical criticism provides a means of connecting the knowledge-making and ethos-building practices of the gift economy with existing studies of fan literatures and fictions. If online fan artwork is a gift used to build artists' ethos and contribute to fan knowledge, then fans have an investment in producing work that both supports their interpretations of the fannish objects and adheres to existing community attachments. The attempt to do both at once is a fundamentally rhetorical practice. Turning toward rhetorical criticism of fan fictions thus offers new possibilities for understanding community construction and meaning making. As Jenkins, Ford, and Green have contended about modern participatory media, "if it doesn't spread, it's dead" (2013, 1); persuasion is yet another element of media spreadability.

3. TPP's neoreligious imaginary

[3.1] Developed by an anonymous Australian programmer and launched February 12, 2014, TPP was pitched as "crowdsourced gaming" (Souppouris 2014). By entering controller commands in the chat feature that runs along the right side of the game (A, B, Up, Down, Left, Start, etc.), viewers of the game's Twitch.tv stream could control an emulated Pokémon Red Version (1998 for Game Boy) being live-streamed. Rather than each viewer having his/her own game to play, every streamer simultaneously enters commands into one game. When thousands of people are logged in at once, the avatar moves erratically, and the game progresses monotonously slowly, but most of the active community agreed that this was part of TPP's charm (video 1). Some observers believed that the game could not be beaten, but the players finished in only eighteen days (note 2). While TPP is technically an ongoing event, it is broken up into generations. Each time one game is beaten, a new game is begun. For this project, I analyze work from the first generation, which took place from February 12 to March 1, 2014. This is because while the generations are connected to one another by their recurring fandom and similar mechanics, the storylines are distinct, and it is this first generation that drew attention from media outlets from Kotaku to Business Insider.

Video 1. Twitch Plays Pokémon game footage from day 3. Here the avatar moves erratically as hundreds of players enter commands together to try to get past a few small walls.

[3.2] What makes TPP particularly interesting as a case study is the evolution of players' experiences of the game. Because the chat feature moved too quickly for thorough discussion and because deliberate player actions were muddled down in a sea of input from other players, fans fundamentally remade the story of Pokémon Red based on their modded experiences. For example, in Pokémon Red Version, players receive a helix fossil which can later be revived to get a pokémon called Omanyte but that otherwise serves no future narrative purpose and cannot be used by the player. Because the object cannot be tossed or used before being revived, it is always in the player's inventory. During battle, TPP's gamers often accidentally opened the items menu and tried to use it, which prompts a text box: "Oak's voice echoed in your head: this isn't the time for that." After doing this past the early giggles, into tedium, and beyond, the TPP gamers began to refer to this as "consulting the Helix." A religious authority, the Helix became a spiritual guide for the imagined dazed and confused avatar.

[3.3] The practice of assigning significance to TPP's chaos makes TPP a particularly useful object of study because, without the developed narrative that would exist in television or in many other video games, fan community interpretation is absolutely central to the way the game's mythology is imagined and enacted. Similar studies of digital game communities have emphasized the importance of fan sense-making practices. Colin Milburn, for instance, notes that computer-savvy users of the player-constructable online virtual world Second Life construct a "nanovirtuality" in which they engineer and realize new world possibilities (2008). While these practices are playful, Milburn also notes that they are very seriously intended to construct viable virtual worlds that satisfy player desires to see their experiences and expectations reflected. While not a virtual world or MMO, TPP functions similarly; the chaos of TPP not only affords the possibility for expansive fan mythmaking, but it is also the starting point for the construction of game canon. Contrary to games such as Second Life, which emphasize player control, TPP's interface is defined by the fundamental lack of direct single-player agency. Further, while players were sometimes able to band together to accomplish collective goals, the chaos of such a practice is resistive to collaborative gameplay as well. The game does not behave. As illustrated by the anecdote about the helix fossil, most of the community-interpretive fictions attempt to cope with this lack of agency. They create meaningful explanations for perceptively mundane game events.

[3.4] To describe the emergence of TPP's interpretive fictions, I will focus on one event I consider the game's defining tale: the release of Abby, the players' first pokémon. Most Pokémon games have the same formula. The avatar is a child given a monster, called a pokémon, by a local professor. This first pokémon, called a starter, is particularly powerful. The gamer is sent out with this starter to capture and train new pokémon so that she can take down eight regional gym leaders and challenge the Elite Four, the strongest trainers in the region. TPP started largely that same way. The players chose Charmander (a fire type) as their starter and named it Abby (note 3). With Abby, they beat the earliest section of the game fairly easily. However, the gamers accidentally released Abby just three days into the game. At this defining moment, the gamers were tasked with moving forward without their most powerful pokémon. The solution came in the form of Pidgey, a small bird pokémon who until that point had done little for the party but who was now its strongest member. This Pidgey later became extremely powerful and single-handedly defeated most of the eight gym leaders. It would come to be known as Bird Jesus, the god-sent hero of the story and its representative figure.

[3.5] The religious symbology of characters such as Bird Jesus is not atypical of fan communities and is in fact frequent in cult fandoms. Combatting essentialist views that fans use religious symbolism as either pure parody or genuine devotion, Matt Hills describes these appropriations as the "neoreligiosity" (2000) of cult fandom. He sees neoreligious speech as a sense-making practice somewhere ambivalently between parody and genuine devotion, which "seeks to account for its attachments by drawing self-reflexively and intersubjectively on discourses of 'religiosity' and 'devotion'" (2002, 96). While J. Caroline Toy suggests, fairly, that Hills's term is simply another artificial distinction that ignores that religion has always been a hermeneutic category (2017), I find Hills's term serviceable not only for its political intervention against perceptions of cult fandom as detached or radical but also precisely for its abstract ambivalence about the nature of fannish attachment. Neoreligiosity can offer a kind of counter-hermeneutic for religiosity. Both emphasize ritual, community, and stable mythologies, but where study of fan (secular) religion centers devotion, the study of neoreligiosity centers discourse and play. Thus, while we should not take lightly Jennifer Otter Bickerdike's reminder that fan attachments make up much of our most meaningful spiritual experiences in the twenty-first century (2015), I take seriously Andrew Crome's suggestion that we should ask how religious symbology supports fan sense-making goals (2014). Thus, I classify TPP's use of medieval Christian and ancient Egyptian form as neoreligious because the term captures the parodic but involved stylistics of TPP's rhetorical forms. This is clear across the fannish discourse, perhaps illustrated most clearly by the humorous bowing emojis that usually bookend all instances of the fandom's favorite chant: "つ _༽つPRAISE HELIX ༼つ _༽つ."

[3.6] Of particular import to TPP's neoreligious interpretive fictions and to this article is the guiding trope of sacrifice. After the release of Abby, sacrifice becomes a major component of TPP's neoreligious eschatology, beginning as an analogue to Christian martyrdom. Looking at the parable above, Bird Jesus is only loosely analogous to Christ, as he has no death or resurrection within the story himself. Instead, the Christ story is bifurcated; Bird Jesus stands in as the savior, but it is Abby (and another pokémon nicknamed Jay Leno) who are the story's sacrificial lambs. Yet even in this playful demonstration, the corollary to Christ is significant. In fact, the not-quite-fit of the Christ narrative is a good indicator that some other sense-making need was involved in the decision.

[3.7] While Christian martyrdom is about making sense of sacrifice, it is also an attempt to elide sacrifice, accepting the necessity of the death but rendering it an exceptional outside event. As Georges Bataille argues, "in the idea of the sacrifice upon the Cross the very character of transgression has been altered. That sacrifice is a murder of course, and a blood one…but the sin of crucifixion is disallowed by the priest celebrating the sacrifice of mass" (1986, 89). While despair and mourning are driving experiences in the Christian metaphor, the Christ anecdote subsumes loss under a greater narrative of transcendence, emphasizing the particular and always-already-historical anecdote of Christ, crucifixion, and Judas. As my next section demonstrates, such work first emerges out of an attempt to anoint Bird Jesus as Abby's spiritual successor.

4. Medieval Christian artwork and rhetorics of visual arrangement

[4.1] Fan art is uniquely suited to illustrate TPP's neoreligious style because, as Rudolph Arnheim suggests, images "hover somewhere above the realm of 'practical' things and below the disembodied forces animating these things" (2004, 137). For neoreligious fandoms, fan art can be what brings the things worshipped and revered into being in the first place. Some of the most popular posts about TPP, particularly in the first week of the event, support the application of Christian eschatology by utilizing medieval Christian art styles. Medieval art styles in particular are often held as culturally emblematic of Christian art writ large, as much modern Christian artwork has maintained the centering of Christ, general proportions of the human body, and stylistic elements such as haloes and highly symbolic objects held by Christian figures popular to these styles (Nagel 2012, 41–45). Yet by using the medieval style in particular, TPP fans also assert an older temporality on TPP's mythology, giving it the performance of a religion that has the longevity of its Christian corollary. TPP fans adopt pre-existing conceptions that, in ancient Christian artwork, "religion overtopped the common affairs of life as the cathedral dominated the surrounding country" (Baugh 1948, 115), centering religious devotion as the guiding principle of any social engagement. The reality of medieval life is not so simple, but the rhetorical strands of such a belief are at work in medieval Christian art styles. As Jonathan J. G. Alexander asserts, medieval Christian art was both a form of religious literacy and "an ideological system that served to represent medieval society to itself" (1993, 1). Such artwork staged contemporary events as religious parables evoked during conversations of social concern (4–7). As with TPP's response to the chaotic loss of Abby, such turns were often an attempt to paint a broader context for current events by centering the workings of a higher power (30). As Alexander notes, such artwork looked to demonstrate that "the world represented in religious images is indeed the world of common sense" (36).

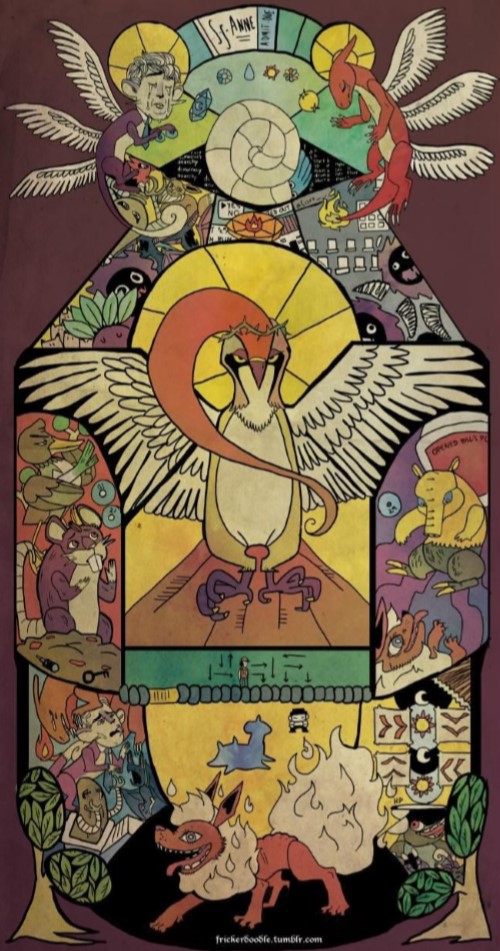

[4.2] Much of the current research on medieval Christian artwork emphasizes ornamental features and figural arrangement of these pieces to determine the relational lessons that artwork was meant to share (Mitchell 2015, 8–10). TPP artwork in this style similarly adopts a common rhetoric of arrangement that visually situates objects in relation to one another, often for the purpose of establishing contrasts and alignments. For example, Frickerdoodle's Days 1–7 (2014) (figure 1), shared on day nine, appropriates the design of late medieval altarpieces. Notable for the eye-catching abundance of gold in backgrounds and haloes as well as the positioning of various parables in different frames of the image, the altarpiece form allows Frickerdoodle to make specific suggestions about the overarching space of TPP's mythology by staging story parables in relation to major characters. In this case, the left and right sections of this piece are symmetrically divided into six parables from the TPP universe with Bird Jesus in the center. Another figure, called Flareon, is set below Bird Jesus. In the mythology of TPP, Flareon plays antagonist to Bird Jesus's rise. Somewhere between Judas and Anti-Christ, Flareon is imagined to have plotted to release Abby to take her place on the team, earning Flareon the name "the false prophet." False idols were often given prominent places in medieval Christian artwork to represent those outside the church (Camille 1989). At the lowest point on the work, Flareon represents hell while Bird Jesus, in the center of the work, stands in for divine purpose. Above Bird Jesus and in further contrast to Flareon, Abby and Jay Leno are portrayed at the top with the six wings of seraphs.

Figure 1. Frickerdoodle, Days 1–7. Posted February 21, 2014.

[4.3] In religious imagery, visual arrangement is often used to distinguish real and sacred space and time (Pollini 2012, 71–73). Frickerdoodle's Days 1–7 similarly separates realms of divine possibility. The four panels on either side are morally and relationally situated within this arrangement. For example, a sad and confused Rattata (called Dig-rat) on the left looks out of its parable toward the guiding image of Bird Jesus, aligning him with both lost player agency and positive moral practices of devotion. Meanwhile, on the opposite right side, Flareon's banishment is portrayed with another pokémon (called the keeper) looking downwards toward the False Prophet's cage. By allowing these figures to gaze out of their frames and toward the sacred and profane symbols in the work's center, Frickerdoodle blends literal and sacred time and space to present an imaginary in which scripture is in a current state of alignment, ascribing narratives of causality in retrospect of the traumatic loss of Abby. Days 1–7 essentially serves to commemorate the loss of Abby and to provide an origin story for Flareon. If Abby's release is the tragic mechanism that makes community mythmaking necessary, the emphasis on arrangement—and thus on the need for an opposite, balancing figure—shifts the rhetorical exigence onto the co-creation of the evil figure which is purportedly responsible. The arrangement of these figures is both a practiced performance of the community's shared experience and a rhetorical attempt to suggest new associations and valances. This artwork may be alien to an audience outside the TPP community, yet both its figures and stylings speak to a common experience for those in the know.

[4.4] I am not suggesting that medieval Christian style becomes a mandate on TPP art or that individual artists definitively persuade the community to think one way or another. In practice, fans still have a lot of space to try out new forms and play with new interpretive fictions; however, the frequency with which popular appropriations of this form are shared and become popular indicates the stickiness of visual arrangement as a form of reasoning. For instance, while some artwork proposed a counternarrative that claimed Flareon was misjudged (MangaFox156 2014) or was absolutely inconsequential (inferno988 2014), such work almost never utilizes the medieval Christian style. This style has been used to arrange moral binaries, and as such it does not fit their goals. Such artwork was not discussed, upvoted, or replicated nearly as frequently as works that used the medieval Christian style to contrast Bird Jesus and Flareon. Rather than calling either the rhetorical form or the attachment to Flareon as antagonist causal, it is useful here to recognize that the popularity of moral arrangement is imbricated with the trajectory of the fan mythology.

[4.5] The rhetorical nature of this work becomes particularly evident when, in the middle of the event, the fan grammar, popular styles, and rhetorical forms began to change, and with them fan relationship to sacrifice. To demonstrate this change, I take a closer look at fan argumentation taking place on TPP's subreddit and at the ancient Egyptian art style used frequently in the later days of the event.

5. The Egyptian turn

[5.1] Eleven days into the stream, TPP experienced another major catastrophe. Nearing the end of the game, the players would soon have to face the Elite Four, a series of difficult trainers and the final boss of Pokémon Red Version, but since Bird Jesus was the only party member strong enough to face the Elite Four (out of a team of six), they decided to catch an extremely powerful legendary pokémon called Zapdos. They managed to capture the creature without accidentally killing it, which is no small feat, but it was sent to the computer system that stores pokémon not currently in the party, the same system used to release Abby and Jay Leno. The players retrieved Zapdos from the computer system, but in doing so they accidentally released twelve other pokémon, an event which players began to refer to as Bloody Sunday in reference to the infamous 1972 Bogside Massacre.

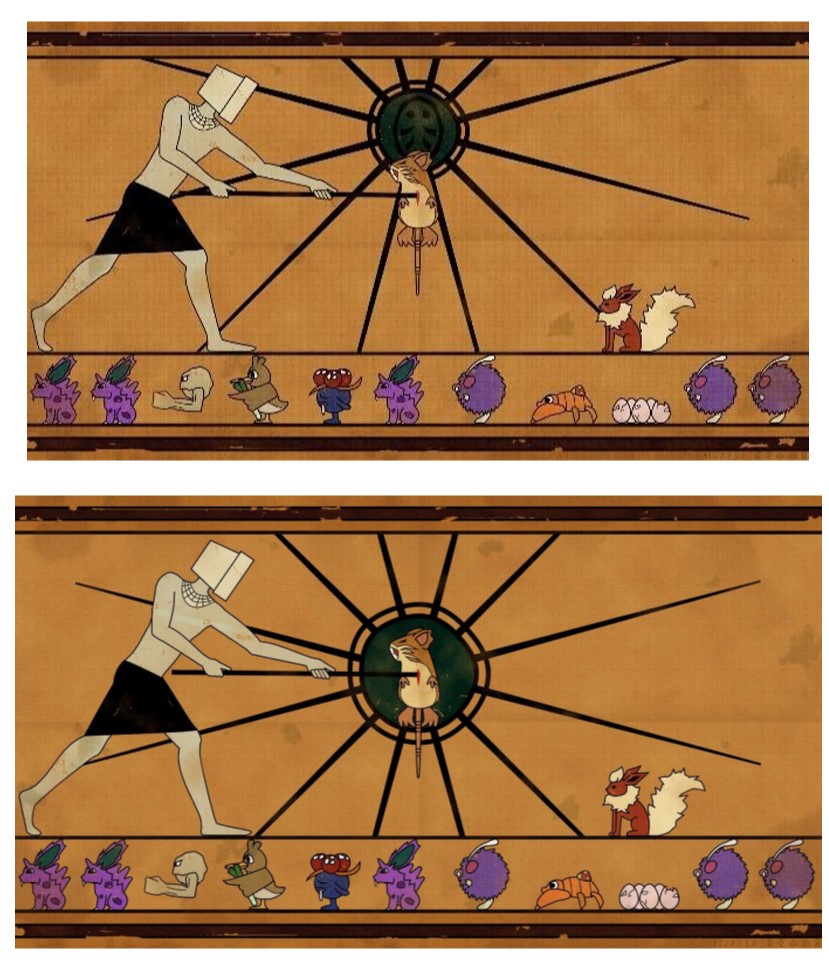

[5.2] To make sense of this event, Redditor Aeuma shared a piece called The Massacre of Bloody Sunday (2014) (figure 2) on day twelve. Done in a mock ancient Egyptian style, the work depicts a man with a computer for a head sacrificially stabbing a pokémon with a spear while Flareon watches from the side. Lined below this are the other eleven pokémon that were released. Behind the skewered pokémon is depicted the dome fossil. An alternative to the helix fossil (players can choose one or the other in Pokémon Red), the dome fossil is associated with Flareon and similarly representative of evil forces in TPP. The work thus uses moral-arrangement-style associations to label the event evil. However, responses to the work were dissatisfied with the black-and-white portrayal of Bloody Sunday. On TPP's subreddit, commentators unpacked, interpreted, and largely rejected the interpretation presented by Aeuma's piece. Respondents took Aeuma's work as the impetus to assert a different perspective. The resulting dynamic is what Virginia Kuhn calls a "digital argument," a fannish rhetorical statement "for which evidence is provided, that also retains a dialogic or conversational nature" (2012).

Figure 2. Aeuma, The Massacre of Bloody Sunday, with Dome fossil (above) and edited version without Dome fossil (below). Posted February 24, 2014.

[5.3] The highest-voted comments make it clear that Aeuma is effectively tapping into a mutual sense of the gravity and affective play around the loss of the twelve pokémon, but they also question the relationship between sacrifice and evil. Agreeing with the artist's portrayal, a few Redditors chose to blame Zapdos for the tragedy, aligning it with the dome fossil. SteakAndNihilism, for instance, warns the community that it is mistaken to assume Zapdos is a hero figure, mimicking the diction of the King James Bible to perform the neoreligious imaginary: "and lo, do they praise the son of perdition, even seeing the carnage he hath lain upon our brethren" (quoted in Aeuma 2014). However, these comments are outnumbered by attempts to read sacrifice as sacred and necessary. NeoNugget says that "Zapdos required the sacrifices to join our party" (quoted in Aeuma 2014). Coltand says that Zapdos is "the hope we need in these dark times…He may not be the hero we all want right now, but he's the one we need. I thank Helix for this small mercy" (quoted in Aeuma 2014). This frame of thinking dominates the board. As the community began to see these sacrifices as a somber but natural phenomenon in the TPP mythology, a few users pressured the artist to change the original work, and later that day, Aeuma released a version of the piece without the dome fossil in the background (Aeuma 2014).

[5.4] In this discussion, both the work and the community's relationship to sacrifice are figuratively transformed (though literally dependent on the work of a receptive artist) by the community discourse as respondents such as NeoNugget and Coltand argue that these sacrifices are better folded into a narrative of progress. The relationship to Bloody Sunday expressed in this conversation is notably different from the Christ narrative created for the release of Abby. More Old Testament, they canonize Bloody Sunday as a valuable sacrifice. In fact, this conversation is indicative of a greater shift taking place in the event's later stages which is best illustrated by the ancient Egyptian style used in this work.

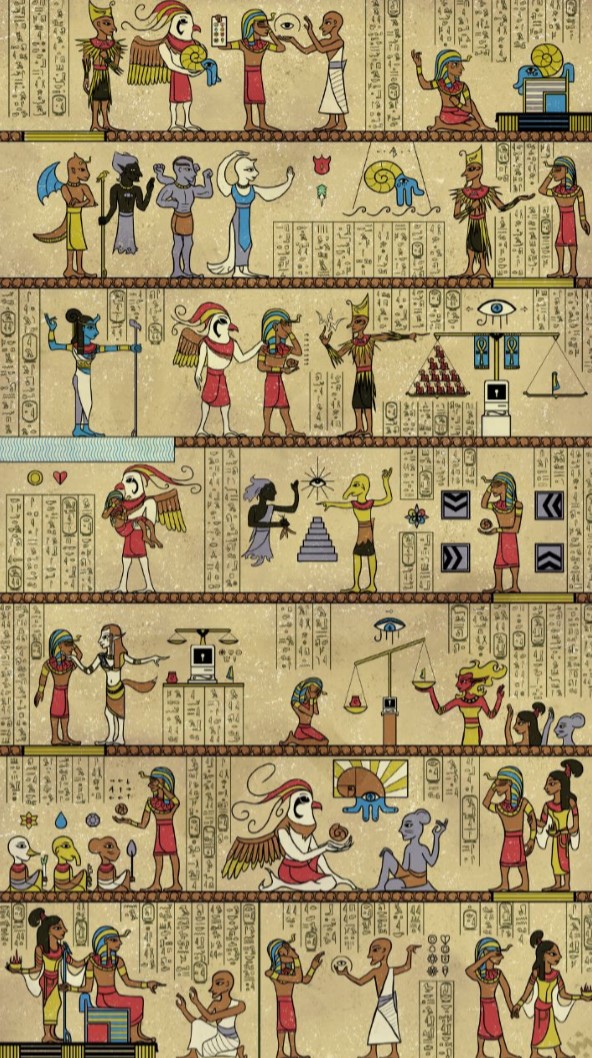

[5.5] The ancient Egyptian art style became more common after Bloody Sunday, particularly inspired by multiple works by Aeuma and another artist called Whoaconstrictor. Art done in this style embraces, rather than mourns, both loss and the game's lack of player agency. For instance, using mock ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, Whoaconstrictor's The Origin of Ancient Helixism (figure 3), posted soon after the first generation was finished, represents major anecdotes in the series—including the death of Abby and Bloody Sunday—as a tale about a young pharaoh. The pharaoh shields his eyes with one hand throughout this journey, symbolizing both the loss of agency and players' inability to truly understand the events around them. In each section, he is guided by the hand of one of his pokémon: first Abby, then Bird Jesus, and eventually Zapdos. Only at the end of the journey, when the players defeat the Elite Four, does he uncover his eyes. In this final frame, he kneels to worship Lord Helix, the TPP god himself. This figurative blinding foregrounds the importance of anarchy and randomness to this journey and flattens all moments before Helix's resurrection into ritual. Whoaconstrictor—who produced a line of Egyptian-themed artwork that was so convincing that an Egyptian tourist shopping mall mistakenly featured it prominently on its storefront (Bridgman 2015)—describes his generic choice: "I really like the way Egyptian art tells sequential stories and the way they anthropomorphize animal-like gods" (Whoaconstrictor 2014). These two elements—sequential storytelling and anthropomorphism—play heavily into the rhetorical transformation that happens in the later days of TPP's imaginary.

Figure 3. Whoaconstrictor, The Origin of Ancient Helixism. Posted on March 13, 2014.

[5.6] Often discussed in comic book and sequential art studies, visual sequential storytelling uses temporal strategies for eliding some details while lingering on others. While Frickerdoodle's work distinguishes the sacred time/space of figures such as Flareon and Bird Jesus from the historical time of the surrounding parables, Whoaconstrictor's work embeds this mysticism into the parables themselves. Even though The Origins of Ancient Helixism represents parables about both success and failure, these parables are holistically wrapped into the entire sequence of the journey rather than considered individually for some moral valence. As Hayman and Pratt note, sequential artwork often relies on strategies of juxtaposition, demonstrating rhetorical moves by what has changed and what remains the same from frame to frame (2005, 423). For The Origins of Ancient Helixism, the various pokémon that serve as guides for the pharaoh are juxtaposed with one another, demonstrating both the continuity of the journey and the frequent sacrifices along the way. That Bird Jesus carries the pharaoh in the fourth frame both illustrates the violent loss of Abby in the previous parable and, by nature of its transition from one frame to another, immediately moves on. Similarly, the continuous reproduction of the blind pharaoh makes it all the more impactful when, in that final panel, he does uncover his eyes and completes his journey. This juxtaposition accents the avatar's compounding loss, a loss he cannot fully comprehend with his eyes covered but which, in the final frame, highlights the relationship between sacrifice and eventual success.

[5.7] While studies of ancient Egyptian art indicate that, in actuality, such work "served the ordered cosmos, which was celebrated on behalf of the gods and which humanity, as represented by the king, and the gods defended against the forces of chaos" (Baines 2007, 335), the recurrent emphasis on sacrifice and Whoaconstrictor's portrayal of a blind pharoah demonstrates a very different relationship to this artistic style. Rather, The Origins of Ancient Helixism draws on an orientalist mix of curious mysticism and fear visible in American popular culture films about ancient Egypt (note 4). The mystique of Whoaconstrictor's work simultaneously renders the experience alien and imparts on it a sense of gravitas. This orientalist perspective has its roots in the American renaissance tradition, in which many writers fascinated by Egyptian hieroglyphics foregrounded sacrifice (Irwin 1980, 129). There writers began to use ancient Egyptian art styles to think about the literary trope of human sacrifice not as something to be avoided but as a necessary step for powerful "transfiguration, transubstitution, resurrection, and ascension" (129) which nonetheless implies a mysticized otherness. Combined with the two-dimensionality of The Origins of Ancient Helixism, Whoaconstrictor's personification of the game's monsters makes the mythology feel more uncanny, alien, difficult to interpret, and literally distanced in history.

[5.8] That TPP fans actually do know what is happening in each parable mobilizes this mysticism, as the othering strategy for accepting the unknowability of the experience is accompanied by fan recognition of their own experiences of the game. Whoaconstrictor's work and other art in the ancient Egyptian style drives players to paradoxically adopt this otherness as their own, to accept themselves as uncanny. Here, the position on sacrifice looks much like Georges Bataille and Jonathan Strauss's reading of Hegelian sacrifice in which man "revealed and founded human truth by sacrificing" (1990, 18). Rather than seeing sacrifice as an exception, sacrifice is elevated to sacred necessity in this position, giving it a simultaneous spirituality and superiority. That this perspective is taken up by the community is evidenced by its later practices of reverence. For instance, while earlier in the game, players would mourn the loss of Abby whenever the computer used to release her appeared on screen, this changed in the later stages of the event. Especially after Bloody Sunday, players began to chant "the PC demands the blood of the innocent" whenever the dangerous device was near, performing their lack of agency and surrendering to the needs of an external and supernatural force. Here, chaos and design collide; the sovereign becomes one and outside. Accepting the loss of agency, players recapture it rhetorically by invoking the irresistible thrall of a god that requires sacrifice for no purpose other than that it demands.

[5.9] Note that not much has actually changed about TPP's canon. Bird Jesus is still good, Flareon still evil. Abby's sacrifice was as essential before as it is now. However, the turn to Egyptian styles invokes a new temporality and rhetorical form. Turning from arrangement toward procedurality emphasizes the how question of the journey rather than the why question of moral alignment. While the arrangement of medieval Christian artwork sectioned out possibilities for sacred time separate from the journey and constructed clear moral binaries between good and evil figures, their use of sequential storytelling adopts a more ambivalent narrative of progress. The reverence of medieval Christian rhetorical forms gives way to the intentional and impenetrable otherness of mock Egyptian anthropomorphism.

6. Conclusion: Rhetorical criticism and digital fandom

[6.1] TPP warrants deeper research into rhetoric in fan discourse. Using neoreligious strategies to cope with figurative loss, TPP fans utilized medieval Christian and ancient Egyptian art styles to make sense of their networked game experience. These artistic styles are entangled with specific rhetorical forms, forms that serve as sense-making tools but that, in their continued reproduction in TPP artwork, also set the conditions of possibility for interpretive fictions. I do not wish to make the claim that this process is deterministic. As Matt Hills has argued, much of the development of fan communities and mythologies is driven not by clear syllogism or argumentation but by "affective play" (2002, 14). Once fans establish a resonance with existing understandings and engagements, they often begin to test the boundaries of not only their primary artifacts but existing fan literature as well, applying outside influences and sometimes entirely new approaches. Yet, with these limitations in mind, TPP demonstrates that the study of rhetorical form can still tell us a lot about what kinds of decisions a community is making and how they make them.

[6.2] The study of rhetorical form in fan behaviors takes on new import for artifacts that support collective online play, including experiments in player agency such as TPP or virtual worlds such as Second Life and Minecraft. Here, collective sensemaking is front and center in the production practices of fans who are exploring and inventing worlds together. This dynamic is not entirely new to digitality. It is not as if discourses were defined by absolute knowability before the internet. Canon is loose. Facts are hazy. Plots have holes. However, artifacts such as TPP are distinctly defined by this sense of unknowability and by the collective desire to explain. As Nick Yee suggests about the player-enacted narratives and ethics in Eve Online, virtual worlds are pliable depending on user perspectives but calcify under the continued existence of user styles of thinking (2014, 63–67). TPP illustrates how such calcification of a style of thinking is interwoven with continuous experience of the object, fan production, and the rhetorical forms that inform discursive arrangement.

[6.3] In Life on the Screen (1995), Sherry Turkle suggests of sensemaking in virtual worlds, "We are learning to live in virtual worlds. We may find ourselves alone as we navigate virtual oceans, unravel virtual mysteries, and engineer virtual skyscrapers. But increasingly, when we step through the looking glass, other people are there as well" (1995, 9). Life after the digital is not as radical as Turkle may have first imagined, but fandoms such as TPP are still navigating virtual oceans together. We need to understand the discourse through which they come to understand these experiences. Fan studies and rhetorical criticism offer tools to help to resolve each other's issues, issues that, for each, ironically tend to emerge most in the study of networked media. Rhetorical criticism provides the methodological tools for engaging fan dialogue as situated, impactful, and oftentimes persuasive, as creative responses that build on or diverge from discursive structures but that are nonetheless informed by the affordances and constraints of those structures. Meanwhile, fan studies provides rhetorical criticism with a framework it is sorely lacking, particularly in the age of the internet: a perspective on the multivocal space of creative, playful, and meaningful entanglement.

7. Notes

1. Both Suzanne Scott (2008) and Matt Hills (2002, 66–68) have suggested that fan arguments are a major component of sense-making practices. This is particularly true in digital environments, in which argumentation is a huge portion of fan interaction (Kuhn 2012). Argumentation plays a vital unifying role in fan communities around participatory media such as video games (Taylor 2006) and virtual worlds (Steinkuehler and Duncan 2008), which do not offer the same kind of unified canon that more linear works might. This is particularly important to this article because TPP is simultaneously a gaming artifact and a digital community.

2. One experimental study of the game's mechanics concluded that after the game became larger than 46 players, even a group of Pokémon experts was not guaranteed to win (Chen 2014).

3. In the emulated game they actually named it "ABBBBBBK," but they referred to it colloquially as Abby, most likely because it was catchier and easier to say.

4. Films such as The Mummy (1999) capitalize on orientalist legends of untold riches, magic curses, and sleeping mummies to build a combined sense of adventure and horror presented by the remains of ancient Egypt (Bernstein and Studlar 1997). Since American "Egyptomania," during which Egyptian iconography was used popularly in American architecture, art, film, literature, and other cultural artifacts, this prevalent mysticism has been a powerful racializing force in film (Shohat 1991).

8. References

Aeuma. 2014. [Art] The Massacre of Bloody Sunday. Fan art. Reddit, February 14, 2014. https://www.reddit.com/r/twitchplaysPokemon/comments/1yrfhp/art_the_massacre_of_bloody_sunday/.

Alexander, Jonathan J. G. 1993. "Iconography and Ideology: Uncovering Social Meanings in Western Medieval Christian Art." Studies in Iconography 15:1–44.

Anneuh. 2014. I Can Show You the World. Fan art. Deviantart, February 25, 2014. https://anneuh.deviantart.com/art/I-can-show-you-the-world-436610528.

Applewaffles. 2014. Bird and Savior. Fan art. Deviantart, March 6, 2014. https://applewaffles.deviantart.com/art/Bird-and-Savior-438647335.

Aristotle. 2007. On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse. 2nd ed. Translated by George A. Kennedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arnheim, Rudolph. 2004. "Pictures, Symbols, and Signs." In Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Sourcebook, edited by Carolyn Handa, 137–51. Bedford. NY: St. Martins.

Baines, John. 2007. Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bataille, Georges. 1986. Eroticism: Death and Sensuality. Translated by Mary Dalwood. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Bataille, Georges and Jonathan Strauss. 1990. "Hegel, Death and Sacrifice." Yale French Studies. 78:9–28.

Baugh, Albert C. 1948. A Literary History of England. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Bernstein, Matthew and Gaylyn Studlar. 1997. Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film. New York: Rutgers.

Bickerdike, Jeniffer Otter. 2015. The Secular Religion of Fandom. London: SAGE Publications.

Bridgman, Andrew. 2015. "Oh Wow—An Egyptian Mall Thought Twitch Plays Pokémon Fan Art Was REAL Hieroglyphs." Dorkly, March 24, 2015. http://www.dorkly.com/post/73528/oh-wow-an-egyptian-mall-thought-twitch-plays-pokemon-fan-art-was-hieroglyphs.

Burke, Kenneth. 1969. A Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Camille, Michael. 1989. The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, Scott Deeann. 2014. "A Crude Analysis of Twitch Plays Pokémon." Computer Science and Game Theory. https://arxiv.org/abs/1408.4925.

Crome, Andrew. 2014. "Reconsidering Religion and Fandom: Christian Fan Works in My Little Pony Fandom." Culture and Religion. 15(4): 399–418.

Frickerdoodle. 2014. "Days 1–7." Fan art. Tumblr. http://frickerdoodle.tumblr.com/post/77405165838/derples-days-1-7-of-twitch-tv-plays-pokemon.

Hall, Stuart. 1997. Introduction to Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage. 1–12.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. 2017. "Icons, Appropriations, and the Co-Production of Meaning." In Rhetorical Audience Studies and Reception of Rhetoric: Exploring Audiences Empirically, edited by Jens E. Kjeldsen, 285–308. Bergen, Norway: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hayman, Greg, and Henry John Pratt. 2005. "What Are Comics?" In A Reader in Philosophy of the Arts, edited by David Goldblatt and Lee Brown, 419–24. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Hellekson, Karen. 2009. "A Fannish Field of Value: Online Fan Gift Culture" Cinema Journal. 48 (4): 113–18.

Hills, Matt. 2000. "Media Fandom, Neoreligiosity, and Cult(Ural) Studies." Velvet Light Trap. 46:73–84.

Hills, Matt. 2002. Fan Cultures. New York: Routledge.

Hyde, Lewis. 1983. The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. New York: Vintage.

Inferno988. 2014. "Flareon the False Prophet." Fan art. Deviantart, February 21, 2014. https://inferno988.deviantart.com/art/Flareon-the-False-Prophet-435630927.

Irwin, John T. 1980. American Hieroglyphics: The Symbol of the Egyptian Hieroglyphics in the American Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jenkins, Henry. 2008. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Kuhn, Virginia. 2012. "The Rhetoric of Remix." Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 9. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2012.0358.

Milburn, Colin. 2008. "Atoms and Avatars: Virtual Worlds as Massively-Multiplayer Laboratories." Spontaneous Generations. 2 (1): 63–89.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 2015. Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nagel, Alexander. 2012. Medieval Modern: Art out of Time. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Pollini, John. 2012. From Republic to Empire: Rhetoric, Religion, and Power in the Visual Culture of Ancient Rome. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Scott, Suzanne. 2008. "Authorized Resistance: Is Fan Production Frakked?" In Cylons in America: Critical Studies in Battlestar Galactica. Ed. Tiffany Porter and C. W. Marshall. New York: Continuum. 210–23.

Shohat, Ella. 1991. "Gender and Culture of Empire: Toward a Feminist Ethnography of the Cinema." Quarterly Review of Film and Video. 12 (1–3): 45–84.

Souppouris, Aaron. 2014. "Playing Pokémon with 78,000 People is Frustratingly Fun." The Verge. Accessed April 20, 2016. http://www.theverge.com/2014/2/17/5418690/play-this-twitch-plays-pokemon-crowdsourced-gaming.

Steinkuehler, Constance, and Sean Duncan. 2008. "Scientific Habits of Mind in Virtual Worlds." Journal of Science Education and Technology. 17(6): 530–43.

Taylor, T. L. 2006. Play Between Worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Toy, J. Caroline. 2017. "Constructing the Fannish Place: Ritual and Sacred Space in a Sherlock Fan Pilgrimage." Journal of Fandom Studies. 5 (3): 251–66.

Turkle, Sherry. 1995. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

TwitchPlaysPokemonHistorian. 2014. "Twitch Plays Pokemon—Red—Complete (Real Time)." YouTube, December 9, 2014. Video 11: 41: 41. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2fuxsllwq8Q&list=PLfIss4eoF7hy3DWjL90AdE_zJz7sjQddD&index=4.

Whoaconstrictor. 2014. "A Most Sacred Tablet." Fan art. Reddit, February 21, 2014. https://www.reddit.com/r/twitchplaysPokemon/comments/1yhopy/a_most_sacred_tablet_fan_art/.

Yee, Nick. 2014. The Proteus Paradox: How Online Games and Virtual Worlds Change Us and How They Don't. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.