1. Introduction

[1.1] Fans produce artistic work on the foundation of what is known in the United States as fair use doctrine, which allows certain kinds of appropriation in service of new artistic or cultural content under the set of regulations copyright law provides. Determining what counts as fair use can be especially difficult when it intersects with fandom. Just as the courts often struggle to distinguish fair use from copyright violation, so too, do fans. Casey Fiesler and Amy Bruckman (2014) note, in their study of fan creators and their conceptions of copyright law, that due to copyright law's complex nature, fans have a wide range of understanding about copyright law; however, community norms are strictly regulated. The "gift economy" "is made up of three elements related to the gift: to give, to receive, and to reciprocate." The transformative nature of fan work bolsters the fan ethos. Both of these fan values have parallels to fair use doctrine: the noncommercial nature of the endeavor and the transformation of copyrighted material are central tenets of declaring a fair use (Hellekson 2009, 114). Even with these core principles, fandom has been in negotiation with the law since the days of analog fan creation (Fiesler and Bruckman, 1024; Coppa 2006). Fiesler and Bruckman write, "This is a problem that has only grown along with technology, and if lawmakers, judges, and legal scholars can have reasonable debates about what may or may not be a fair use, then it is not surprising that ordinary Internet users have trouble drawing these lines as well" (1023). Fair use has ramifications for the future of online practices since case law, as it evolves and sets precedents, is not easy to overturn. It looks back to past cases for established precedents even as it attempts to manage current conditions.

[1.2] The history of copyright and fandom is also difficult terrain because there has never been a fan fiction or fan film case to date. For a brief period during the early to mid-2000s, it seemed possible that the long-standing relationships between media corporations and fans would prove stable enough to support negotiations of fan practice outside the legal arena. While the history of these relationships had been tumultuous at times, as corporations occasionally served Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown notices to fans, there were also instances of "tolerated use" from corporations that ran the gamut from private understandings between fans and corporations about nonprofit creation to media corporations' co-option of fan work for their own gain (note 1).

[1.3] The introduction of the internet and the subsequent facility that technology provided for fans in production, distribution, and consumption of fan work further imbricated them in concerns about copyright infringement that arose from both fans and media corporations (Schwabach 2011, 13–20). For some fans, like the community of women vidders who had been producing remix content for nearly thirty years before the internet, the wider distribution and publication model was anxiety-inducing because it could more easily call negative media industry attention to their work. "Vidders exercised caution because they thought they could be sued if they did not… So rather than create centralized archives, as fans had for fan fiction, vidders discreetly offered their vids on individual password-protected sites" (Tushnet and Coppa 2011, 131–32). For media corporations, developments in online production, circulation, and distribution have increasingly blurred the lines between fan films and commercial endeavors (note 2). Although distinctions between amateur work and corporate productions have always been cloudy, the ease of production and distribution that accompanied the introduction of the internet altered the stakes in the difference between them (note 3).

[1.4] As legal scholar Rebecca Tushnet recently put it with regard to fandom and the copyright landscape, "The noncommercial fan community has still not given rise to litigated cases, but the presence of the OTW [Organization for Transformative Works] and increasing awareness of fair use among fans have enabled them to resist copyright owner threats, and in all the instances of which I am aware, copyright owners have decided not to follow up on informal threats when fans making noncommercial uses resisted" (2017, 78) (note 4). While this is certainly true, important to Tushnet's statement and to the fan film landscape on fair use is the phrase "noncommercial uses." The internet challenges what legally counts as noncommercial use, and often the distinctions between the commercial and the noncommercial are not cut and dried, especially when online platforms are involved.

[1.5] I look at what happens when a Star Trek fan, Alec Peters, and his film, Prelude to Axanar, enter the legal arena largely due to legal haziness around online practices, and also look at what happens when the legal arena meets the fan. A case that is the first to negotiate the limits of online fan practices is important because it establishes the terms for future digital copyright cases. More broadly, it aims to balance intellectual property rights with free expression. I argue that Paramount Pictures Corp. & CBS Studios, Inc. v. Axanar Productions, Inc. & Alec Peters (C.D. Cal 2016) reveals the tension between the gift-giving ethos of fandom and online crowdfunding as a type of gift and, alternatively, reveals the negative industrial and legal reactions to fan filmmaking and crowdfunding as threats to the way film has traditionally been constituted. This case does not threaten participatory culture on the whole, for even while increased constraints on the material fan films may use might arise from litigation, fan films will not disappear, even if legal threats disproportionately inhibit the creative reach of some fans (note 5). The rich historical lineage of amateur filmmaking in the United States extending back to the 1920s, coupled with longstanding fan relationships with media corporations and fans' willingness to creatively address legal questions, leads me to believe that fan filmmaking is here to stay (note 6).

[1.6] I consider how the online crowdfunding platforms Kickstarter and Indiegogo expanded the amount of money involved in the Axanar fan film production, pushing it closer to professional productions, even as the campaigns participated in the gift-giving mentality of fandom. In doing so, I also consider calls from the fan community that the Axanar film is not a real fan film because Peters's ethos was not aligned with the gift economy, not fully valuing fan ethics around labor and value. Similarly, Paramount and CBS declared that Peters is not a real fan in their attempt to mitigate damage to their relationship with the Star Trek fan community. The media industries then cement their negative view of fan filmmaking by implying that real fans are not involved in fannish behavior that resembles Peters's, only to release a new restrictive set of guidelines for fan filmmakers that ignores fair use. Finally, I analyze the negative legal reaction to fan filmmaking by aligning it with appropriation art, both as a way to think about the traditional definition of authorship adopted by the media industries and the law, and to propose a new way of conceiving a fair use defense for fan films.

2. Axanar Productions, the gift economy, and fan films online

[2.1] Paramount and CBS opened the case on December 29, 2015, when they filed a lawsuit against Axanar Productions, Inc., and Alec Peters. Peters created Prelude to Axanar, the twenty-minute trailer Star Trek fan film designed to precede his fan film feature-length movie, Axanar. The twenty-minute Prelude to Axanar features several professional actors who play starship Enterprise crew members. The crew members give talking-head interviews as they narrate a Star Trek story that revolves around Garth of Izar, a character "introduced in the Star Trek episode, 'Whom Gods Destroy.'" Axanar "tells the story of the Four Years War with the Klingon Empire, which the United Federation of Planets nearly lost" (http://axamonitor.com/doku.php?id=axanar&s=garth&s=izar).

Video 1. Axanar, "Prelude to Axanar," YouTube, August 15, 2014.

[2.2] Paramount and CBS claim, as the filing lawsuit details:

[2.3] Star Trek has become a cultural phenomenon that is eagerly followed by millions of fans throughout the world. Unlike virtually any other television series or motion picture, the fictional Star Trek races and characters, their technology, personality traits, and even their makeup, have been documented and given a historical texture by Plaintiffs that extends far beyond the action on the screen. Plaintiffs own the copyrights in this treasured franchise…The Axanar Works [Prelude to Axanar and Axanar] infringe Plaintiffs' works by using innumerable copyrighted elements of Star Trek, including its settings, characters, species, and themes…

[2.4] The Axanar Works are intended to be professional quality productions…On information and belief, Defendants have raised over $1 Million so far to produce these works, including building out a studio and hiring actors, set designers and costume designers. (Grossman, Zavin, and Jason 2016, 1–2)

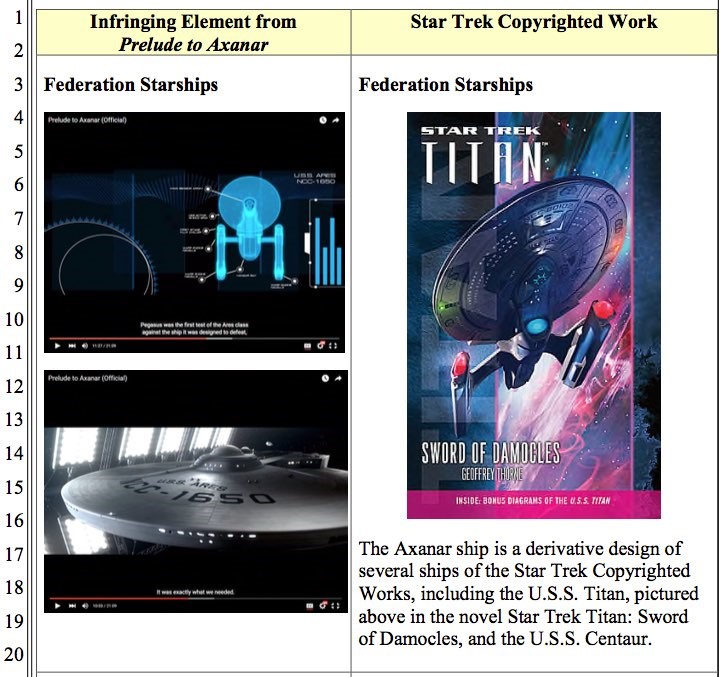

[2.5] After Paramount/CBS filed the lawsuit, Peters attempted to settle outside of court with a Motion to Dismiss, which would void the lawsuit. Judge Klausner, who was assigned to the case, decided that the claims made by both sides merited further consideration. He set a schedule for the continuation of the legal proceedings, which were to culminate in a twelve-day trial in January 2017, but the parties settled the case after Klausner wrote a partial summary judgment that prohibited Axanar from introducing a fair use argument (http://axamonitor.com/doku.php?id=summary_of_the_lawsuit). CBS and Paramount detail the bulk of their complaints in a photographic chart that outlines each of the alleged copyright infringements, with original Star Trek photographic screenshots in the right column and Prelude to Axanar screenshots in the left column. If the court had decided that Peters knowingly infringed on Star Trek's copyright, an act known as "vicarious infringement," each instance on the list would have cost Alec Peters and the other defendants $150,000.00 (http://axamonitor.com/doku.php?id=knowing_infringement).

Figure 1. A visual catalog of infringements from Paramount/CBS's Attorneys in the lawsuit that contains twenty-eight pages of potential violations.

[2.6] In fleshing out the details of the Axanar case, I consider why this fan film landed in hot water. Here, the broader landscape of digital-age fan filmmaking practices around crowdfunding emerges as a type of gift and, alongside it, the dissenting view from the media industries in relation to fan filmmaking and crowdfunding. High-budget films supported by online platforms, including Kickstarter and Indiegogo campaigns, challenge fan activities that in the past were considered amateur (or nonprofessional) practices that did not involve the exchange of money for profit. Through these campaigns, fans can put hundreds of thousands of dollars or more to work (note 7). Even while fans who raise money from crowdfunding sources do not pocket money from these campaigns, US copyright law defines profit more broadly. Judge Klausner describes the issue this way:

[2.7] Although it is unclear whether Defendants [Axanar, Alec Peters, and twenty unnamed defendants] stand to earn a profit from the Axanar Works, realizing a profit is irrelevant to this analysis. The Court can easily infer that by raising $1 million to produce the Axanar Works and disseminating the Axanar Works on Youtube.com, the allegedly infringing material "acts as a "draw" for customers" to watch Defendants' films. (Klausner 2016, 5)

[2.8] Klausner, rejecting the initial claims from the defense who argued that the Axanar works are fair use because Peters did not financially benefit, declares instead that profit does not make a difference to the case's outcome. For Klausner, the "draw" of the work exposes the potential for a derivative market. Derivative markets are a factor in determining infringement (Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510, U.S. 569, 579). Moreover, fan film productions often engage in material creation, including the construction of film sets, soundstages, and other items that fans then disseminate in association with their fandom. While this materially based practice historically extends to the analog production and circulation of fanzines, it has taken on new functions in the digital age—incentivizing potential donors to participate in crowdfunding campaigns in exchange for fan creations (note 8).

Figure 2. Alec Peters in Prelude to Axanar, playing Fleet Captain Kelvar Garth.

[2.9] While the media industries look down on this type of fundraising as a "draw" that opens up the potential for a derivative market, fandom understands fan fundraising of all kinds as a gift. Both the money from the crowdfunding campaigns and the resulting fan creations they support are part of the reciprocal gifting and receiving of the gift economy. Even beyond the commercial and noncommercial distinction that the media industries are concerned with, fandom makes finer-grained regulations about the power and labor of fan creations. As Mel Stanfill (2015) explains, the labor of fandom "contains the accumulated labor of both the corporate maker and the fan remaker" (131) and "fan norms distinguish clearly between copying from those with more power and those with less… Fans need to credit…other fans' work, whereas they feel free to mine the outside world for raw material, as long as the resulting works stay noncommercial" (136). However, defining the legal borders between the gift economy and the commercial economy is not a simple matter.

3. Axanar and the gift economy

[3.1] The evolving nature of online practices extends funding possibilities into the realm of commercial competition, affords breadth of distribution across media platforms, and enables higher production values and an ability to pay industry professionals. While fan practices that are important to Axanar, including financial donations, replica set construction, and the use of professional actors, existed before the internet, the ability to crowdfund staggering amounts of money through online platforms is a new development, and it made many of Peters's other actions possible. For copyright lawyer Mary Ellen Tomazic (2016), these are the details that pushed Peters into dangerous territory: First, Peters created Kickstarter and, later, Indiegogo online crowdfunding campaigns for Prelude to Axanar and Axanar that totaled $1.4 million and used some of the Kickstarter net of $571,044.86 to pay two staff members and himself a salary (http://axamonitor.com/doku.php?id=gofundme). Second, he created perks for donors according to the amount that they donated to the Axanar film campaign. The perks, as Paramount and CBS claim, were also infringing items (note 9). Third, he used the funds to start Ares (now Industry Studios), which Peters planned to use to film Axanar and to rent to others (note 10). Important to note about fan film studio filmmaking is that several other fans have built studio sets that contained "standing sets," which stay in the studio and are used only for the fan film. For example, prominent fan filmmaker James Cawley houses his USS Enterprise sets in what was previously a Ticonderoga, New York, dollar store. In Cawley's case, he received a license from Paramount/CBS for the sets and they are open to the public (Post 2015). Building and/or using sets, therefore, is not limited to Axanar. However, Peters's interest in renting the studio to other filmmakers indicates his potential interest in profit, and, Peters did not seek a license from Paramount/CBS. Fourth, Peters hired a professional crew, several of whom had worked on the original Star Trek series (Tomazic 2016).

[3.2] I concentrate now on the Axanar Kickstarter and Indiegogo campaigns, since they are the impetus behind many of Peters's actions and fuel the commercial/noncommercial legal issue. The crowdfunding strategies Peters used to fund Axanar Productions are aligned with methods a host of other Star Trek fan films have used, although Axanar outraised all of them. Jonathan Lane, who writes the Axanar Fan Film blog, traces the history of Star Trek fan films and the use of Kickstarter campaigns from the first—Star Trek Excalibur—to the present slew of campaigns. While he is strongly in favor of Axanar because he runs the company website, he gives the fullest account of Star Trek fan films and funding in relation to Peters that I have located. He also details what Peters learned from the success and failure of earlier campaigns, which is illuminating for the case. Lane writes, "From the earliest days, Star Trek fan films had relied on the kindness of donors—whether it was passing the hat among the volunteers who came to help out on a shoot, getting the occasional gift card from Lowe's or Home Depot, or begging for donations via PayPal" (2016a). Kickstarter, then, expanded an ongoing practice.

[3.3] After a series of failed fan film crowdfunding campaigns, the first successful one was Star Trek: Renegades. This campaign bears similarities to Axanar in the use of professional actors and the use of perks for donors at various funding levels. The perks for Renegades' Indiegogo campaign included items such as posters, digital film downloads with special features, access to exclusive web content, DVD and Blu-Ray versions of the film, commemorative patches, and, autographed ephemera (https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/star-trek-renegades#/updates/all). Peters's project differs from Renegades in that some of his patches include trademarked images. An Axanar fan highlight of the perks Peters created are the patches bearing Star Trek images renamed with Axanar labels.

Figure 3. Axanar patches for Kickstarter donors as investment incentives.

[3.4] The images on the patches are bound to the question of whether or not Peters impinged on Paramount/CBS's derivative market. Peters himself stated in the Santa Clarita Valley Business Journal in 2015, "More and more content needs to be developed…It's not just broadcast anymore; it's Amazon, Netflix, and Hulu. When people saw our 20 minute short film we got buzz in the industry—better than anything J. J. Abrams [the director of two Star Trek films] is doing." Peters cites Renegades as one of the campaigns that taught him about crowdfunding.

[3.5] What I did before we launched the Prelude Kickstarter was I spent a lot of time paying attention to what Star Trek: Renegades had done in their Kickstarter…and then what they had done in their Indiegogo. I went through and made lists of all their perks and figured out what the best levels for different perks were. Our first Kickstarter video for Prelude was based off the Renegades video…But that's a basic principle of business: modeling. (quoted in Lane 2016c)

[3.6] As the funding campaigns progressed, Axanar Productions launched its first campaign in March 2014 with a goal of $10,000. Lane (2016a) recalls, "A short 'talking head' video featured Alec Peters, Director Christian Gossett, and most notably, actor Richard Hatch (plus a few others) talking excitedly about the project and the professionals who were coming on board. There were also eye-catching 3D effects shots done by Tobias Richter scattered throughout the video…they finished at $101,000 from 2,123 donors. This allowed them to make the 20-minute Prelude to Axanar." All of these examples are thus well within developing Star Trek fan film crowdfunding practices.

[3.7] In the next Kickstarter campaign, Axanar set a record for the amount of money raised for a fan film.

[3.8] With less than two days to go before the Kickstarter deadline, Axanar's total stood at a whopping $400,000. And that would have been considered staggeringly good, but then something even more amazing and totally unexpected happened: George Takei posted to his Facebook followers (all 8.5 million of them!) that they should check out the Axanar Kickstarter and donate to it if they wanted some real Star Trek…Axanar rocketed upwards to finish at $638,000 from 8,500 backers…This was a new Kickstarter record for any independent Star Trek film. (Lane 2016a)

[3.9] That was the last Kickstarter campaign Axanar launched before it switched to Indiegogo, another crowdfunding site that, unlike Kickstarter, allows users to keep the money they raise regardless of whether they reach their final financial goal. For donors, this introduces more risk (Lane 2016a): funds could be raised in the name of a project and never come to fruition due to budget constraints. When Peters switched to Indiegogo, the platform gave him a boost, "offering them discounts on fees along with a special three-day 'pre-launch' period open only to previous donors…who would be offered exclusive perks and let Axanar's campaign launch with numbers much higher than zero" (Lane 2016a). While the Indiegogo campaign failed to take in as much as the original Kickstarter, it took in about $475,000 from 7,400 backers after the initial thirty-day campaign finished (Lane 2016b). Lane (2016c) also notes that Axanar took advantage of Indiegogo's "In Demand" tool, "where, if you surpass your goal, you don't have to end your campaign. I know that Axanar took in an additional $100,000 in the six months after their 30-day Indiegogo campaign 'ended.'" As Axanar Productions amassed unprecedented sums, it challenged the boundaries between a fan film and an independent, commercial production that could divert consumers away from Star Trek.

[3.10] The tension between crowdfunding viewed as a gift within fandom and as a threat to the media industries is further complicated by calls from some Star Trek fans, many of whom initially supported the Axanar project. These fans say that Peters is not a real fan, since he wasn't invested in the foundational principles of the gift economy and violated the ethical rules of fandom. A parallel example of a violation of fandom's rules that illustrates fans' rejection of Peters is the story of the company FanLib. FanLib, founded in 2007 by three industry men, attempted to sell largely female-produced fan fiction online. Karen Hellekson (2009) provides details about the company's attempt: "Although outreach included targeting and emailing fanfic writers and encouraging them to upload fic to the site in exchange for prizes, participation in contests leading to e-publication, and attention from the producers of TV shows like The L Word (Showtime, 2004–present) and The Ghost Whisperer (CBS, 2005–present), FanLib's persistent misreading of the situation alienated fans, as did the draconian terms of service…FanLib broke the rules of the community's engagement by misreading 'community' as 'commodity.'" The rejection from the community led to the site's closure in 2008 (117–18). The company's persistent misreading of "community" for "commodity" is strikingly similar to how Peters treated his own fan film production—a community of Star Trek fans became financial backers for a commodity (the Axanar feature film) that Peters never completed, eventually alienating many of the fans who were his financial supporters. For many of these fans, Peters's financial disclosures, which appear redacted in the public court files, are a source of dispute and anger (http://axamonitor.com/doku.php?id=no_refunds&s=nda).

4. Paramount/CBS and restrictive fan film guidelines

[4.1] If it already seemed like the media industries were not fond of new online developments in fan filmmaking in light of the lawsuit, a few months later, they drove the point further home on the Star Trek website by introducing a set of restrictive guidelines for fan filmmakers (http://www.startrek.com/fan-films). This was clearly a response to issues with the Axanar film and other fan films already online, although they avoided calling out fans by name. The site stated, "The content in the fan production must be original, not reproductions, recreations or clips from any Star Trek Production…The fan production must be a real 'fan' production, i.e., creators, actors and all other participant must be amateurs, cannot be compensated for their services, and cannot be currently or previously employed on any Star Trek series, films, production of DVDs or with any of CBS or Paramount Pictures' licenses." As for Paramount and CBS's definition of commercial works as opposed to noncommercial works, some of their specifications included the following restrictions: (1) fundraising cannot amount to more than $50,000; (2) the film can only be exhibited free of charge; (3) the film cannot be distributed in DVD or Blu-Ray; (4) the film cannot generate revenue for the fan producers through advertising; (5) fans are prohibited from distributing unlicensed perks in connection to their fundraising efforts; and (6) fan productions cannot garner revenue from selling or licensing fan-created props, sets, or costumes.

[4.2] The guidelines are extensive—the industries go as far as to cap the length of fan films at fifteen minutes and require that the films only contain "family friendly" material that, in a perhaps unintentional nod to the Motion Picture Production Code, "must not include profanity, nudity, obscenity, pornography, depictions of drugs, alcohol, tobacco, or any harmful or illegal activity, or any material that is offensive, fraudulent, defamatory, libelous, disparaging, sexually explicit, threatening, hateful, or any other inappropriate content." The statement would seem to target nearly every kind of popular fan film, not to mention fan fiction, currently produced—from fan remix films and Kirk/Spock slash videos to the production of replica sets—without regard for fair use. Henry Jenkins notes, "I can't think of any currently available fan films that would come anywhere near meeting the expectations here and the guidelines would prohibit many forms of practice that would be explicitly protected under current understandings of Federal law regarding parody and transformative use" (quoted in Miller 2016). In other words, the guidelines put forward by Paramount and CBS are not legally binding and have no legal sway. Their purpose is to prevent fans from embarking on large-scale fan film creation out of fear that media industries will prosecute them.

Figure 4. Part of a replica Star Trek set housed in an old dollar store in New York, created for a fan film series called New Voyages. This set was licensed by Paramount/CBS to fan and set creator James Cawley.

[4.3] As Paramount and CBS attempt to regulate fan filmmaking, their methods conform to ways that media corporations have co-opted fan work for their own use, as Suzanne Scott details in "Repackaging Fan Culture" (2009). Academics, fans, and acafans, she argues, have rhetorically cordoned off the commercial economy from the gift economy in scholarship and sometimes in fandom, too, as though they are separate. She indicates that this is not the reality of how economies of fandom function. By overwriting the continuum between the gift and commercial economies, media corporations can more easily take advantage of fans in subtle ways. One of these ways is through the development of ancillary content that pushes fandom into mainstream spaces by "repackaging" fan work for commercial promotion through regulated terms that the corporation "regifts" to other fans in sanctioned online spaces (Scott 2009). The repackaging-for-mainstream-content model lurks behind the Star Trek fan film guidelines. Channeling the fan films into corporate visions of acceptable creation dampers fan film creation, angering fans and undermining fair use, but it also readies the corporation for egregious co-option of labor, so it can usher it into mainstream fan spaces as it curates its corporate image.

[4.4] The separation between fandom as a subcultural social practice and the mainstreaming of fan culture wherein "fannish values and reading practices spread across the entire viewing public" in ways supported by media corporations is noteworthy (Jenkins 2006). In the mainstreaming of fan practice, media industries use the labor of fandom, whose practices have been altered and molded, in service of another group of fans, ultimately for corporate gain. While mainstream fans might become members of fandom, as Jenkins points out, the Star Trek fan film guidelines place fans associated with fandom in the middle of a tug-of-war between corporations and mainstream fans. This tug-of-war parallels the structure of the Axanar case: where Peters might have taken advantage of other fans' donations and engaged in copyright infringement, the corporation prepares to regift and control fan films, using the labor of one fan group to generate support for mainstream fan platforms. As Stanfill concludes about media industries appropriating fan labor, "The same corporations filing takedown requests on fan transformative works are quite willing to appropriate fan labor by monetizing those works, and they often profit from appropriating other artists who never get to count as artists" (2015, 137). In this scenario, neither Peters nor Paramount/CBS seem especially ethical. There is realized and potential exploitation on both sides.

5. Staking the great plains: Enterprising fair use

[5.1] I turn away from Paramount/CBS's reaction to fan filmmaking to analyze the legal response to Axanar through the case's failed fair use defense. The provisions for fair use are as follows:

[5.2] Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors. (Copyright Law of the United States 2016, § 107)

[5.3] The fair use defense proposed by the Axanar legal team failed because the terms of fan filmmaking that assign authorship to an appropriated work threatens the legal and media industrial constitution of authorship. Stanfill, describing how copyright law views appropriation in fandom, argues that

[5.4] contemporary US culture and copyright law do not recognize this [fan creative labor] as additive, let alone as valid or compensable. As Casey Fiesler notes, the term derivative work 'applies to anything from the slightest modification to something so transformed that the original is hardly recognizable.' … Though the four-factor test of fair use in US copyright law assesses 'the amount and substantiality of the portion used,' this framing operates from a logic of subtraction…This conceptualization haunts transformation with the specter of stealing someone else's work rather than doing one's own. (2015, 132)

[5.5] I suggest another way of conceptualizing fair use wherein fan films coalesce with the legal history of artistic appropriation as transformative works (note 11). Appropriation art, like fan work, faces legal challenges because it stretches the legal definition of an author and, therefore, the concept of an original artwork when it uses other artists' material to generate new art. All art borrows from other art to some degree, since that is the nature of cultural production, but appropriation art, both as a postmodern movement and a distinctive style, "borrows images from popular culture, advertising, the mass media, other artists and elsewhere, and incorporates them into new works of art. Often, the artist's technical skills are less important than his conceptual ability to place images in different settings and, thereby, change their meaning" (Landes 2000, 1). The courts have yet to catch up with artists and their use of appropriation as a historical practice, and consistently litigate these cases, as lawyer Rachel Butt indicates (2010); yet the impact of bringing fan films into alignment with artistic appropriation is that both practices would be considered as part of a longer lineage of respected art practice, increasing the likelihood that appropriation inherent in fan filmmaking might be considered transformative. Appropriation art and fan filmmaking pose similar legal questions, and the law tends to negatively frame both; however, appropriation art has a case history that has established appropriation as part of a transformative practice and has gained legal traction over time.

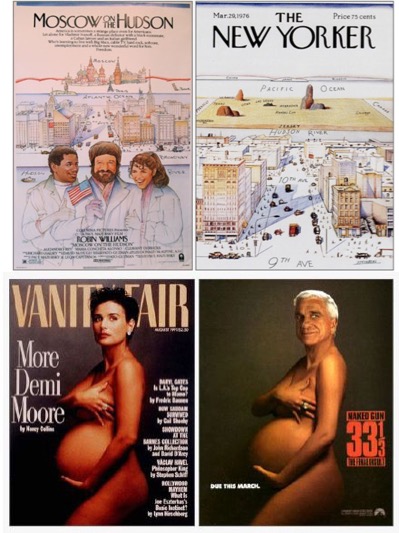

[5.6] Notable early cases involving the uncertain status of appropriation art and authorship extend to lawsuits filed by artists whose work Paramount and Columbia Pictures appropriated for film posters. Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures (1987) and Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures (1998) contained fair use decisions that, on the face of it, are at odds with each other regarding the law's view of appropriation. However, they also uncover that media industries are willing to appropriate artists' work, just as fans do with fan work, and that the law does not readily account for the power differences between individuals and corporations. Judge Stanton, in Steinberg, ruled in favor of the artist, signaling that Columbia Pictures unfairly appropriated Steinberg's art, and Judge Newman, in Leibovitz, ruled in favor of Paramount Pictures, signaling that Paramount's appropriation of Leibovitz's photography was fair use.

[5.7] In Steinberg, artist Saul Steinberg filed a lawsuit against Columbia Pictures for a movie poster that "infringed his copyright for an illustration that appeared on the cover of the New Yorker." The judge "stated that defendants' use of Steinberg's illustration was not a parody and therefore not a fair use because defendants' variation was not aimed at some aspect of Steinberg's illustration" (Butt 2010, 1070). In Leibovitz, photographer Annie Leibovitz filed a suit against Paramount for its Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult movie poster. "The movie poster depicted a naked and 'pregnant' Leslie Nielsen, which was clearly a spoof of Leibovitz's photograph of Demi Moore that was featured on the cover of Vanity Fair in August 1991. Judge Newman held that Paramount's poster constituted a fair use" because it "commented on the 'self-importance' conveyed by the subject of the Leibovitz photograph" (Butt 2010, 1071). The judicial reasoning in both cases sidesteps the power of the media industries and instead relies on traditional ideas about authorship and originality that allow the media industries to take a poor view of fan filmmaking today.

Figure 5. Movie poster at issue in Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures (1987) (top left; Steinberg design top right) and Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures (1998) (bottom left; poster at right).

[5.8] These cases served as early testing grounds for legal authorship in instances of appropriation, and are connected to Tushnet's invocation of the Stone Soup fable that describes how courts think about authors. According to Tushnet, cultural pastiche, one form of appropriation that is pervasive in fan work, will not stand in court, since the legal definition of authorship adheres to Romantic ideas about the individual or corporation as a creator and therefore rejects pastiche. Tushnet notes:

[5.9] Contemporary creative works "often resemble the soup in the fable of 'Stone Soup,' in which a sharp operator convinces a village that he can make soup out of stones—as long as each of the villagers contributes a little bit of meat, vegetables, spices, etc. The resulting dish is delicious, and the stones are a but-for cause of the soup." Copyright law's restricted definition of authorship is a bit like "say[ing] that the stranger with the stones is the true owner and proprietor of the soup." (quoted in De Kosnik 2016, 190)

[5.10] The Stone Soup fable, then, articulates why early appropriation art cases like Steinberg and Leibovitz had little legal standing and also partly explains why the Axanar defense, reliant on cultural pastiche and mockumentary as the basis for transformation, failed. Next, I briefly elaborate on the Axanar defense to outline how the defense's approach to authorship broke with more traditional authorial notions before turning to the evolution of appropriation art in legal cases, which in the future could support a more comprehensive view of transformation.

6. Axanar and the fair use defense

[6.1] The limits of fair use emerge as attorney Erin Ranahan sets up her argument. The fair use argument, as Ranahan conceives it, positions Peters's Axanar works as transformative works that are part of a history of noncommercial Star Trek fan filmmaking. She removes distractions, such as Peters's questionable use of crowdsourced donor funds, from the four conditions of fair use to divert attention from the legal grey area that has yet to define profit in relation to crowdfunding. For Judge Klausner, however, the funding campaigns sway the case in favor of Paramount/CBS, since the outcome of the campaigns divert attention away from the original series.

[6.2] Ranahan continues her argument regarding transformation as fair use. She argues that the latest Axanar script contains "50 original characters, an original plot, dialogue, timeline, and story" (Ranahan, Hughes Leiden, and Oki 2016, 1). She asserts that the Axanar works have had absolutely no measurable effect on the market for Paramount/CBS, suggesting instead that the fan film keeps interest alive (note 12). She indicates that Prelude to Axanar should be understood as a "mockumentary" and that while certain characters, including Kirk and Spock, are copyrighted, Peters's works "do not include those or any other characters to which Plaintiffs own separate copyrights" (3). The defense's misstep here has to do with their definition of mockumentary, which in their argument, is a central feature of Axanar. While their intent was to define Axanar as a film that drew from a range of cultural productions, and at the same time, move the judge toward a transformative use ruling, the plan backfired because authorship is so categorically slim. The cultural pastiche argument, as Tushnet suspected, could not hold weight on its own.

[6.3] When the term mockumentary appears in the defense's analysis, it rings false—the film does not suggest that its spirit was one of parody, nor was it advertised to the public as such. While Prelude to Axanar includes talking-head interviews in a style that is distinct from the original Star Trek series and films so as to comment on the original (Ranahan's definition of the term), mockumentary does not fit. A mockumentary would conceive of Axanar's audience reception as one that is read as "parody, hoax, pastiche, or active critique," which is how film scholar Cynthia Miller conceives of the term (2012, xiv). More important than the question of whether it is or isn't a mockumentary is the problem of the court defining how people interpret media created for a specific audience without the audience's input (note 13). Ranahan points to a commentary ruling wherein a work that has a "completely different purpose" from the original weighs in favor of fair use:

[6.4] The narrative style of Prelude, which has never before been seen in Plaintiffs' Works, is reminiscent of historical documentaries on famous wars and their impacts on society. This style allowed Defendants to add critical commentary and analysis in order to highlight a comparison of concepts in the Star Trek universe to the present-day military industrial complex, thus serving a 'completely different purpose' than the solely entertainment-focused Plaintiffs' Works. (Ranahan, Hughes Leiden, and Oki 2016, 16) (note 14)

[6.5] Leaving aside scholarly analyses of Star Trek: The Original Series that would take issue with the assertion that it is "solely entertainment-focused" and therefore must not contain critical commentary, her overall point is that Axanar is a cultural pastiche, drawing from many sources. Therefore, she asserts, it does not copy any substantial part of Star Trek (Ranahan, Hughes Leiden, and Oki 2016, 4). While the defense intended to define Axanar as a film that is more expansive in pastiche than Star Trek alone, the law could not support that definition of authorship.

7. Law, appropriation art, and transformative works

[7.1] I now turn back to appropriation art to track how its case history gained legal standing with regard to fair use, and analyze what fan filmmaking might take from the cases' progression. Notable early examples of artistic appropriation in Western art that art historians recognize as part of the lineage of contemporary appropriation art include Pablo Picasso's and Georges Braque's cubist collages (1912 on) and Marcel Duchamp's readymades (1915 on) (www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/appropriation).

Figure 6. Picasso's Collage Still Life with Chair Caning (1912) (left) and Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917/replica 1964) (right).

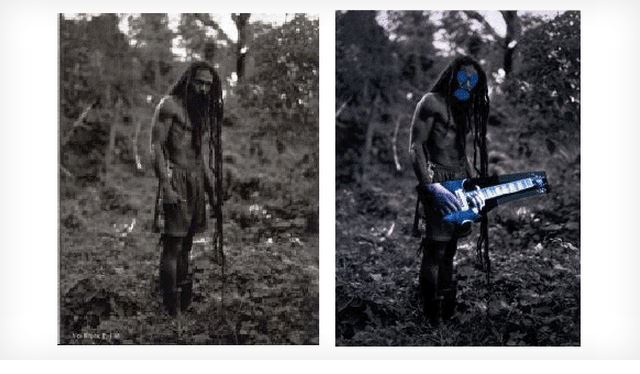

[7.2] Early copyright cases involving appropriation art became well-known and broke new ground with Jeff Koons's artwork in a series of trials (McEneaney 2013, 1530–33). As lawyers Anthony Gilden and Timothy Green indicate, appropriation art, on the whole, has found slightly easier standing for fair use as postmodern art has developed status in the art world (2013, 88) and this plays out in the Koons cases among others. Koons's appropriated work in Rogers v. Koons used a photograph-turned-postcard of a man and woman holding puppies as the basis for a sculpture, String of Puppies (1988), in which Koons altered characteristics, like color, of the original artwork. The Second Circuit court rejected a parody defense in a summary judgment. Later cases that have had a more sympathetic view of Koons's work include Blanch v. Koons (2006), in which Koons used a Gucci advertisement for a painting. Here, the Second Circuit court found Koons's work to merit fair use protection (Katyal 2014). Even while the courts have not settled on the practical limits of what they consider to be transformative in fair use cases, linking fan practices with artistic appropriation indicates that appropriation is an established art practice that sometimes grants the second artist authorship rights.

[7.3] An Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts amicus curiae reply brief in support of Richard Prince's appropriated photographs from artist Patrick Cariou states that Campbell v. Rose-Acuff Music decided that a work is transformative if it "'supersedes the objects' of the original creation…or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message [and] there are many uses beyond commentary or criticism that deliver new meaning and expression and provide important 'social benefit[s]' that equal or exceed those provided by parody or direct commentary" (Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., quoted in Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts 2012, 2). Campbell was a landmark case, establishing the transformative use prong of fair use in 1994 (McEneaney 2013, 1530).

Figure 7. Patrick Cariou's photograph (left) and Richard Prince's appropriation art (right).

[7.4] Pinning down a particular meaning or criticism is not necessary to understand the transformative nature of a work, for as the Warhol Foundation argues about Prince's work, "The fact that meaning is difficult to verbalize, label, categorize or explain does not mean Prince's work is not transformative. It simply reflects the fact that the meaning of visual art does not always translate neatly into written words (The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts 2012, 5)." As such, the transformative nature of the Axanar works, or other fan films, does not need to be rigidly defined to be declared transformative. The fans themselves could aid in such a ruling, for they are the best readers of Axanar.

[7.5] Tushnet suggests to the courts as they determine transformative use rulings that they should seek "epistemological humility" and ask the community for whom these works were made (2013, 20). More than anyone else, the fans can contest and attest to the nature of the films, even if the community itself is divided about the outcome of the case (http://axamonitor.com/doku.php?id=reader_commentary).

[7.6] To make fair use work, courts should assess transformativeness from multiple perspectives, with attention to what different audiences might see in a work and in an allegedly transformative remix of that work. There is some risk that this approach will simply transfer the problem of defining who counts as a 'reasonable' audience member, but the existence of communities of practice—whether appropriation artists, vidders, or others—who react to the new work as having a different meaning than the original could help establish that such audiences are both reasonable and real. (Tushnet 2013, 29)

[7.7] Assessments by Trekkers, who would not be hard to locate due to Star Trek fandom's visible online presence, could support a transformative use defense.

8. Trekking the digital frontier

[8.1] As Star Trek fans and filmmakers encounter the legal frontier of copyright law and embrace the tools that the digital age has provided, the limits of fair use come into focus. Each new copyright case establishes how the courts interpret fair use doctrine, how creative expression can be used to create meaning, and how far copyright ownership extends. Paramount/CBS v. Axanar intervenes at a crucial juncture in the trajectory of digital age copyright law, pressing the court to negotiate the terms of fair use as they pertain to fan practices, including crowdfunding and appropriation, that the digital age extends and makes possible.

Figure 8. The original Star Trek reflexively meets the American western for a shootout at the OK Corral in 3.1 "Spectre of the Gun" (1968).

[8.2] The case challenges the relationship between fans and media industries, putting pressure on the legal definition of a fan as the case attempts to name certain practices as fan practices and others as non fan practices in ways inauthentic to fans' expressions of love for media creations. It emphasizes that the gift economy of fandom is central to the constitution of a fan. When Peters rejected the values of the gift economy, he was sanctioned within the fan community, losing much of the support he had garnered for his project. The conflict between the gift-giving mentality of fandom and the negative responses to crowdfunding and fan filmmaking from media industries and the law speak to the nature of the uncharted legal territory between commercial and noncommercial endeavors. It also casts light on the conservative definition of authorship for both as participatory culture in the United States develops alongside digital technologies and platforms.

[8.3] The case renegotiates the terms of intellectual property ownership on the digital frontier. After applying the four-prong fair use test, Judge Klausner decided:

[8.4] The Court thus finds that all four fair use factors weigh in favor of Plaintiffs. If the jury does not find subjective substantial similarity [to Star Trek works], Defendants did not infringe and fair use defense is moot. If the jury finds subjective substantial similarity, the Axanar Works are rightfully considered derivative works of the Star Trek Copyrighted Works. Rejection of Defendants' fair use defense is consistent with copyright's very purpose because derivatives are "an important economic incentive to the creation of originals." (2017, 13)

[8.5] He removed Axanar's surest path to winning, which was rocky to start; but most concerning about this partial summary judgment is that short of Axanar arriving at trial, it established legal precedent in the United States for fan films and the use of copyrighted material that does not look favorably on fan film creation.

[8.6] Given the circumstances, this abrupt finale might turn out to be an optimal outcome for fan films. The caving defense argument for a case that should not be the poster child for fan films leaves room for future fair use defenses that argue differently for transformative use. On the one hand, Klausner's judgment seems like a sharp blow to fan film creations, but it may not turn out to be as stifling as one might think. The logic of the ruling is embedded in a cultural battle between artistic containment and resistance (Hall 2006). Klausner does not reject the idea that fair use could protect fan films. On the other hand, precedents are difficult to reverse. Only the future will tell how this precedent stands in copyright cases to come, but it is unequivocally a case that breaks new ground. Star Trek fans, lovers of a quintessential space western, venture to go boldly where no one has gone before. In doing so, the fans recapitulate a defining tension inherent in the American Western and in American jurisprudence: the tension between property ownership and "free territory," set on the legal stage—once again exploring a new land.

9. Acknowledgments

[9.1] I thank Alenda Chang, Constance Penley, Janet Walker, and Charles Wolfe for their insight and valuable feedback.