1. Introduction

[1.1] Many considerations of the modern fan experience and participatory culture are intrinsically tied to changes that new media technologies have brought in the last 20 years (Jenkins, Ford, and Green 2013; Booth 2010). With the rise of Web 2.0 and the ubiquity of social media platforms, constant immersion in online social content is a standard part of modern life. For those who live in these digitally enabled worlds, there may be changes in the nature of social interactions (Jacobs and Cooper 2018), with closeness among friends fostered by constant awareness of what they are doing. Through incremental small updates of seemingly banal content, this "ambient intimacy" (Reichelt 2007) is constructed. The rise in mobile digital technology means that this closeness can be carried with us wherever we go. When the overlay of digital and physical spaces is complete, modern fans, and more generally people who regularly use connected digital devices, can constantly coexist in both the physical world the ambient digital world. This includes bringing digital interaction into what might traditionally have been considered off-line fan spaces, such as conventions.

[1.2] Conventions for fans date back long before the digital age; for example, the annual World Science Fiction Convention, Worldcon, has been run almost continually since 1939. These conventions provide opportunities for those sharing particular interests to meet and make connections. Booth (2016) describes fan conventions as a unique constructed space where fans connect in a particular moment of both space and time. Today, "online meetings that may first take place in a chat room or via a message board are reinforced by fan conventions" (Costello and Moore 2007, 134). Friendships extend to those who have not yet experienced a face-to-face meeting. As the boundaries between digital and real life blur, it does not seem unlikely that there would be a desire to share experiences with those who cannot be physically present but are part of the virtual community. This is of particular interest when considering activities encompassed within the context of some conventions that are traditionally associated with the notions of liveness and exclusivity.

[1.3] Questions of digital inclusion have been examined in the context of music fans. Bennett, writing about the shared experience when digital technology is used to connect fans who are physically present at a music concert with those who are remotely engaged, argues that this practice of "involving the non-present audience" is a way for fans "to contest and reshape the traditional boundaries of the live music experience" (2012, 553). Sharing is a key part of the fan experience for many fans; however, some disagree that this outside engagement for live events is beneficial, especially given that the value inherent in these unique experiences is dependent on having been there. Those who have this privileged position enjoy elevated status, a value inherent to the limited nature of the experience: "For some audience members the value of the concert may be that it is not available to anyone not present; from their perspective the intensity of performer/audience communication is undermined by its communications to people not present" (Bennett 2012, 554).

[1.4] Those who sell tickets to live events may share this exclusionary view, depending on their business models. Models of fan conventions range from not-for-profit conventions run entirely by volunteers, to large commercial enterprises with professional paid staff. This variation may be linked to the type of celebrity guests whose attendance boosts ticket sales. Fan-run conventions, particularly for literary-focused fandoms, seldom pay fees or honoraria for speakers, instead perhaps covering travel, accommodation, and food for the guests (note 1). Guests at such events are usually writers or artists, many of whom are fans themselves and likely attended these conventions in that capacity earlier in their careers (note 2). Television- and film-focused events often invite actors, who are generally less likely to have been existing members of fan communities and who are often contractually obligated to charge for public appearances. These appearance fees must be covered either by the convention organizers or as a proportion of sales for items such as autographs and photographs with fans. This may encourage a more commercial model overall. Such commercial events have become an important income stream for many actors (Goldberg 2016). In this context, tickets to attend events are a high-value commodity rather than an attempt to fund an expression of collective interest.

[1.5] The conflict inherent in these two modes of conventions, between commercial sale to groups of individuals versus shared production and consumption, echoes more general questions over the nature of digital public space (Jacobs and Cooper 2018) and the consequences of convergence culture (Jenkins 2006). What constitutes public content remains ambiguous, including the copyright status of fans exchanging GIFs and remixed content. Further, although fans may perceive the conventions to be public spaces, to commercial organizers, they are private, paid shows. The desire fans have to share freely with others conflicts with control of access, and new technologies can emphasize these divides. In order to address these conflicts, fan studies must undertake interdisciplinary work understanding the concerns of multiple stakeholders including fans, media industry professionals, and other commercial organizations (Jenkins, Ford, and Green 2013).

[1.6] In considering the current and future progression of the fan experience, technologically driven changes in social norms must be addressed. Some of these behaviors and processes are in flux, thus providing a unique opportunity to direct these interactions toward positive social change and sustainable business models. Here I examine a case study of the evolving policies and practices of a particular form of digital sharing: video recording and live streaming at Creation Entertainment's Supernatural conventions. The use of technology for sharing at these events has gone through several iterations and levels of conflict as attending fans and event organizers have negotiated their stances. The digital footprint of these events is a new contested space, with different pressures from the community, convention celebrity guests, and Creation Entertainment.

2. Context: Supernatural conventions and online fandom

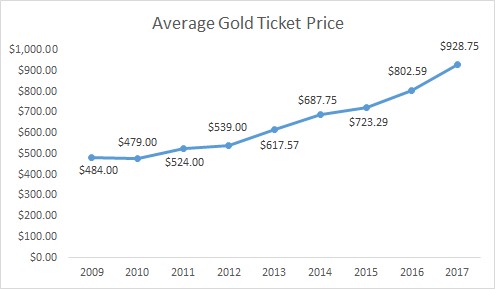

[2.1] The television show Supernatural began in 2005 and is still airing, making it one of the longest-running US genre shows. It has a large and active fan base. Conventions attended by the stars of the show have been held since 2007, and multiday events now take place many times per year. These include a variety of activities, including question-and-answer panels with actors and often musical events such as karaoke and Saturday Night Special (SNS) concerts. In 2016, twenty-four conventions were held worldwide, seventeen of them in North America. These North American events are run exclusively by Creation Entertainment (https://www.creationent.com/company.htm), a company that has been running commercial comic and science fiction conventions since 1971. Although Creation Entertainment runs conventions for many properties, the Supernatural events might be considered distinct. Vist (2016) describes the events as a magic circle of playful intimacy between the cast and fans. This unique status is facilitated by two main factors: the events are hosted by members of the cast (usually Robert Benedict and Richard Speight Jr.) (note 3) who develop this shared space, and many fans travel to attend multiple conventions per year, despite prices that are far higher than other Creation Entertainment events (note 4). This price differential may be the result of demand, or it may be because fans are willing to pay increasingly higher prices—in 2017, almost $1,000 for top-price packages (figure 1), with some fans paying over $1,500 for premium front-row seats.

Figure 1. Average prices for Gold tickets to Creation Entertainment events. These tickets include priority seating, autographs, and exclusive content. Data collected and compiled by Twitter user @TeganJ42; it has been verified and is used with permission.

[2.2] Despite the popularity of these events, the relationship between the fans and the company is not unequivocally positive. Booth has critiqued Creation Entertainment's mercurial approach to conventions: "Creation Entertainment represents the resistant/complicit state of fandom within the industry" (2016, 24). The events follow a rigid format, heavily centered on interaction with the celebrities rather than fans sharing their own experiences, critical analyses, or transformative readings. Booth notes, "Creation largely reifies the fan-as-consumer practice of fandom" (2016, 31). This urge to maintain control of both the experience fans have at the events and their interaction with the objects of their fandom and each other is demonstrated through their effort to control, and later commodify, the practice of sharing experiences beyond the boundaries of the convention itself, explored below. Booth notes, "Creation's remit to focus on celebrities and authorized readings of the media program foregrounds a devotion to the original text at the expense of unauthorized fan activity" (37).

[2.3] While conventions play an important role in the world of Supernatural fandom, digital social media fan interaction is also important. Supernatural is one of the most talked-about US television shows on digital social platforms. Rebak (2016) tracks mentions of Supernatural across 80 million websites from August through October 2016 as part of a study of large entertainment fandoms, finding online interaction on platforms including Tumblr, Instagram, and Facebook. Twitter, however, was the most active platform, with 73,976 public users mentioning Supernatural during this period. Rebak (2016) hypothesizes that Twitter is a favored platform because of the practice of live tweeting episodes of the show as they are broadcast, as well as frequent fan engagement by the cast: "Twitter is not only the social media home of Supernatural's most beloved celebrities…[but] it's also where fans go to livetweet every new episode. In fact, the Supernatural fandom was the earliest to start livetweeting like this on a large scale."

[2.4] The strong online community evident in these digital spaces is reinforced by a coherent overarching message that the fans support each other and function as a Supernatural family, as well as the willingness of cast and crew members to engage with fans on various platforms. Here I examine interrelations between the online fandom space (considered by some as a public space) and the private space of conventions. I examine the changing technologies used to bring experience from one sphere to the other, as well as the reactions by various stakeholders.

3. Methodology and ethics

[3.1] My case study uses a mixed-methods approach. I performed initial observational research as part of a community of interest on Twitter that overlapped with community members attending Supernatural conventions. I carried out ethnographic research over a period of approximately eighteen months, from January 2016 to June 2017, including conversations with fans, review of social media data under specific hashtags, and observation of ad hoc commentary and discussion. This included convention content posted online by fans and Creation Entertainment; no conventions were attended in person. Twitter was selected as the main platform for study because this is the primary venue for discussion of conventions by repeat attendees and those sharing content, which may be due to its centrality for real-time fan interaction (note 5). To supplement this ethnographic research, an anonymous online survey was conducted targeted to fans who have an interest in Supernatural conventions, though not excluding those who have never attended an event in person. This study received approval from the University of Aberdeen ethical review board.

[3.2] Individual tweets quoted have been obfuscated to ensure anonymity while preserving the original meaning and intent. This was achieved in one of two ways: transposition of two existing words or phrases in a joint clause, or replacement of a single word by a synonym. Although the tweets are available in the public domain, I decided to anonymize the tweets because fans posting content may not have been aware that their tweets would be used in this context, and therefore conditions of informed consent to identification were not satisfied. It is also important to note that this phenomenological study necessarily represents a particular view of the events that have occurred, filtered through a subsection of attendees and their responses. It should not be taken as representative of the wider Supernatural fan base or the customer base of Creation Entertainment events.

4. Chronology of digital sharing of the convention experience

[4.1] The following is an account of changes in online coverage of Creation Entertainment Supernatural conventions from 2007 to 2017. These events generate much online interaction and discussion among fans, which has taken different forms as technology has evolved. In the earliest years of the conventions, this consisted primarily of footage posted to YouTube. Around 2009, however, Twitter emerged as a key platform for the fandom, with the practice of using Twitter for real-time live-tweeting episode commentary carrying over to the conventions. This heavy use of Twitter has persisted; for example, during the three-week period surrounding the February 2016 Nashville convention, approximately 30,000 tweets used the official hashtag, #SPNNash (note 6).

[4.2] Until mid-2015, text-based commentary on Twitter was the major way for those who were not present to quickly get an idea of what was taking place in real time. Fans attending the event tweeted, but remote fans discussed updates and interacted with those in attendance. The practice of live tweeting what was being said by stars at panel sessions was common; those recording the event in this way indicated this in advance so those interested could follow their tweets. This Twitter commentary was supplemented by multiple postings of full video footage of the panels. This generally comprised five or six videos per panel, posted to YouTube a few hours after the event. Rapid access to these was valued in part because the text-based commentary was perceived as ambiguous because of its lack of tone markers and its abbreviated content.

[4.3] In March 2015, an app called Periscope launched after being acquired by Twitter, reportedly in response to a rival live streaming app called Meerkat (Bohn 2015). Meerkat and Periscope both quickly grew in popularity because these formats were able to leverage existing social networking by integrating directly with the Twitter platform (Tang, Venolia, and Inkpen 2016). By late 2015, Supernatural fans (in particular those with interest in conventions) had also begun to use Periscope. Each convention would attract two or three dedicated Periscope users who would live stream the activities. Links to the best-quality streams would quickly be circulated; these streams acted as a hub for fans within the connected online community, who could also use the platform to provide shared commentary and direct feedback to the person taking the video. This use of Periscope proved extremely popular, especially for music-based activities. Video and audio footage, seen directly in real time, felt part of a more intrinsic communal experience, and it also eliminated some of the issues of misinterpretation and bias seen in text-based relaying of information. Depending on the nature of the content (e.g., the popularity of the actor on stage), viewership varied, but streams would generally attract at least fifty viewers, and up to several thousand for the most popular. For example, at an October 2016 event in Atlanta, a Periscope stream of stars Jared Padalecki and Jensen Ackles had 2.4K viewers, one of Misha Collins had 1.1K viewers, and 240 viewers followed Julian Richings, who guest starred in several episodes. Fans spoke out about how a positive energy came from the experience of seeing live content from the event. Concordant with this, the volume of live tweeting diminished because this was no longer seen as a necessary component of recording and transmitting the event:

[4.4] What nobody intended or anticipated was the sense of community that came from using Periscope, because you could share with other people watching. (personal communication, July 2017)

[4.5] The conventions since their beginning had always nominally had a policy of forbidding video and photography during the panel sessions, with signage to that effect posted outside the event rooms at the venue. However, despite this, there was an unspoken understanding between the organizers and fans that this would not be enforced, and many videos were posted online with no repercussions. This implicit permission, in contrast with the explicit forbidding of posting, was reinforced by hosts of events, who offered advice on the best way to capture footage. The following is a representative quote by Speight from the opening introductory session of a convention, which quotes and then subverts the official rules by referring to online posting of content as free advertising, as seen in video 1.

Video 1. blurino24, "Don't Videotape the Convention," YouTube, January 18, 2015. Richard Speight Jr.'s opening remarks at Salute to Supernatural, San Francisco, CA, January 16–18, 2015.

[4.6] However, in November 2016, Creation Entertainment began to enforce the ban specifically on live streaming, with volunteer staff on site asking fans to stop broadcasting and threatening to eject those who persisted. Fans believed that this was in response to the rising use of Periscope. Reactions on Twitter were vehement that this had strong negative effect on the community:

[4.7] Instead of the normal excited cacophony of ppl chatting about @CreationEnt conventions, my timeline is largely silent and/or bitter. (Twitter, November 2016)

[4.8] Much discussion surrounded the effect that this would have on the wider community:

[4.9] Let us mourn, our feelings are valid. It's more than content or a concert, it's a lost sense of connection. (Twitter, November 2016)

[4.10] Many echoed Speight's comments that access to the events (specifically the music performances of the SNS) contributed to positive marketing for the conventions themselves:

[4.11] Sense of togetherness and family created by SNS periscopes is why so many people are inspired to save up & go to your cons @CreationEnt. You dumbs. (Twitter, November 2016)

[4.12] Discussion followed over the next few months, with fans attempting to contact the company and confirm exactly what the policies were. Some fans publicly shared email responses that suggested that capturing content for personal use was allowed but that sharing full video was not permitted. This correspondence cited reasons such as rights issues and contracts with the talent. The email also referred to jokes made by Speight, suggesting that they did not constitute permission.

[4.13] In December 2016, an announcement was made by the charity Random Acts (founded by one of the stars of Supernatural) that they would be collaborating with Creation Entertainment to broadcast one of the SNS concerts, to be held on January 21, 2017, as a joint fund-raiser for a specific campaign (Schmitz 2016). To do this, a commercial live streaming platform called StageIt was used, which allows people to buy tickets providing access to the stream. StageIt provides the facility to give tips (i.e., extra monetary donations), which were used in this case for additional fund-raising. This event was extremely successful, ultimately raising almost $65,000, and it received much positive feedback from fans, who noted that it allowed participation in the event in a way that was lacking since Periscope was banned.

[4.14] At the end of January, after the charity broadcast, Creation Entertainment confirmed at an event that live streaming by fans would be permitted, but only for the karaoke segment. On February 3, Creation Entertainment announced that it would be hosting its own live streaming service of the SNS concert taking place on February 25, with paid access through purchase of a ticket on the StageIt platform at a cost of $15 to $20.

[4.15] On March 30, 2017, the official Creation Entertainment Twitter feed posted a screen capture of their policy with the caption, "Hey everyone, here is our official policy regarding video recording, photography, and live streaming" (figure 2). Responses to this tweet were positive, with several thanking the company for clarifying their position; however, this official guidance was not immediately available on the company's website, at least not prominently. Therefore, it is questionable whether this clarity would be available for those who did not see the announcement via Twitter or other social media platforms.

Figure 2. Notice posted on Creation Entertainment Twitter feed, March 20, 2017.

[4.16] After the apparent success of the first StageIt broadcasts, Creation Entertainment has continued to provide this service. Starting with the Seattle convention, April 7 to 9, 2017, and at selected conventions that followed, the use of the platform extended beyond the SNS musical event to panel sessions containing interviews with actors, at a price of $5 to $20 per forty-five-minute event. Although uptake has been good and this new technology implementation could be seen as a positive move for the company, fans expressed mixed reactions.

5. Fan attitudes to video sharing: Survey results

[5.1] The survey on convention attendance and use of technology was initially distributed on April 19, 2017, and responses were gathered for the next ten days. The survey link was initially circulated via Twitter, as the dominant platform for this fandom. During this period, 262 responses were collected from members of the community with an interest in conventions. The survey development was in progress before Creation Entertainment had announced that it would be providing its own authorized live streams at conventions, although some questions were amended just before the survey went live to reflect this situation. Responses to the free-text survey questions were not compulsory; responses are reported below as percentages of those who gave an answer to each particular question.

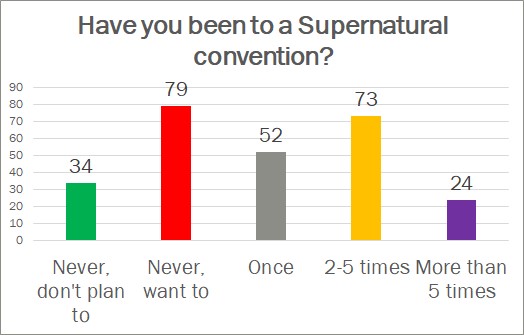

[5.2] Responses included those who had and had not attended the events in person, with 57 percent of the respondents (149/262) indicating that they had attended at least one event, including 9 percent (24/262) who had attended five or more events (figure 3).

Figure 3. Convention attendance rates.

[5.3] Asked if they thought it was good that video from the events was made available online, almost all respondents agreed. Of 233 respondents who answered this question, none gave a negative response and only seven expressed ambivalence, with two specifically noting a difference in how they felt about fan-made videos as opposed to those that were made professionally and charged for. A common response was that it allowed others to join the experience who could not otherwise attend:

[5.4] Fans that cannot afford going to the con can also be a part of it.

[5.5] Another common theme was that it encouraged attendance:

[5.6] ABSOLUTELY YES! The only reason I am saving for a con is because I saw video of it. Before SEEING it online, I had zero interest.

[5.7] Asked "If applicable, what made you first want to attend a Supernatural convention?" 34 percent of respondents (89/262) indicated that experience of this content was a factor. This was the second most common reason cited, after wanting to meet the actors from the show. Sixteen percent of respondents (41/253) cited YouTube when asked how they first learned of the existence of conventions.

[5.8] A common theme seen throughout the responses was that videos provided free advertising for Creation Entertainment. Asked specifically how video footage being made available online affected intention to attend, responses overwhelmingly indicated that it did not have a negative effect: only 2 percent (5/224) indicated that it would make them less likely to want to attend, and 77 percent (172/224) said that it would increase their desire to attend. However, some did again comment that they felt more positively about the freely provided fan videos than the paid StageIt.

[5.9] Comments generally reinforced that while videos were appreciated, they did not substitute for attendance in person:

[5.10] I appreciate when the streams are made available live. You can pretend you're there.

[5.11] Being there in person is the ultimate experience.

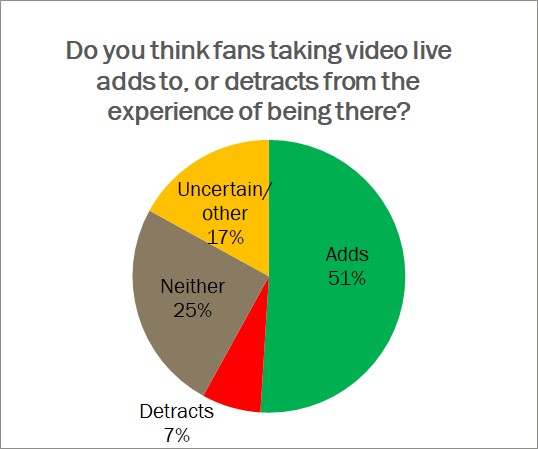

[5.12] Inclusion of a wider audience was also a common theme when asked whether fans thought videos added or detracted to the convention experience (figure 4), a question to which over half of respondents (113/220) gave a positive response:

[5.13] It opens the window for those not there.

Figure 4. Effects of live video on experience.

[5.14] Interestingly, of the small group (7 percent, 16/220) who said it would detract, four suggested that the negative effect would be for those taking the video; the mediation of experience through the camera would mean that they were less able to participate fully:

[5.15] I think for the fan taking the video, it may give them a layer of distance. (I found that tweeting during panels distracted me from being fully present).

[5.16] I believe in living in the moment, so the experience should be special to you.

[5.17] Two fans commented that because of this negative personal effect, while they had no objection to other people filming in this way, they would not do it themselves. However, one fan highlighted the positive effect of sharing with the online community in real time:

[5.18] My fandom community is online. If I'm streaming live video, and I'm getting their responses in comment form, it intensifies my experience of being there.

[5.19] Fourteen fans mentioned the possibility of restricting or blocking the view of other fans present, with several suggesting that whether filming is a good thing depends on if they are causing an obstruction. Several people noted that their experience had been negatively affected by those around them filming. This may be seen as an argument in favor of professionally provided footage that is preplanned and filmed from a fixed point that does not obstruct anyone's view. Another option suggested by respondents was a specific area of the auditorium set aside for those who wish to film, so as not to disturb others.

[5.20] Asked if they considered there had been changes in online presence over the past year and whether this had affected experience, many respondents suggested that restrictions on video had greatly reduced the amount of both footage and interaction online:

[5.21] Ever since they cracked down on the No Live Streaming, the online presence/atmosphere (especially on twitter) has been quiet and there has been less online excitement. During cons where there are not many people live-tweeting/posting it feels like there is not a con happening at all.

[5.22] Asked if they were more likely to watch live or prerecorded content from conventions, the majority (56 percent, 127/228) said that they would usually not watch live. However, over half of these (75/127) said that this was due to timing conflicts, being in the wrong time zone, or being busy with other commitments such as work. Some also cited quality concerns, indicating that low-resolution video or technical issues of live streams would lead them to choose better-quality videos uploaded later. This issue of quality also led to praise of professional videos:

[5.23] like it more when the organizer films and uploads it than fans filming with bad quality.

[5.24] Despite these major drawbacks to live video, 33 percent (76/228) still responded that they are more likely to watch the videos live. Many comments suggested that live viewing was a communal experience:

[5.25] I would like to watch them live, because it would almost feel like I was there, experiencing the same thing so many other people are experiencing.

[5.26] I want to experience it as it's happening, otherwise I hear all the highlights on twitter and am less motivated to go watch later. Watching live as a group is what's fun.

[5.27] Value in the experience was also a factor in how people responded when asked to choose between a high-quality live video and in-person attendance with a poor view. Fifty-nine percent (137/232) said that they would prefer being there in person, using words such as "energy" and "atmosphere." Many expressed the idea that "nothing compares" to being there, and mentioned that being in the space has other advantages, such as meeting other fans and being able to enjoy other aspects of the convention. However, 34 percent (80/232) still said that they would prefer a high-quality live video, with the main factor given being cost: they would not be able to participate in the live experience because of the expense involved. Although the live experience has irreplaceable features such as interpersonal connection and immersion, video allows continuous participation when physical attendance would be impractical, thus permitting fans to maintain a link to the event and the community. Value is indicated in both aspects.

[5.28] Another survey question asked participants how much they thought would be a reasonable price to pay for live streaming of content from the conventions. While a sizable proportion of 20 percent (39/192) responded that they thought videos should be free or they would not be willing to pay for them, most fans were able to put a proposed cost on paying for video content. Over half suggested an acceptable price would be $5 to $10, often indicating a range (figure 5).

Figure 5. Frequency of prices provided in answer to the question, "How much, in your opinion, do you think is a reasonable amount to pay for live video of a panel?" If a range was given, this graph includes the highest figure in that range.

[5.29] Several respondents noted that an acceptable price might vary depending on the length, quality, or content of the stream—for example, a forty-five-minute panel versus a two-hour music show. Some noted the high price of ticket attendance and said that streams should be cheap because of this, or that proceeds should go to charity:

[5.30] No more than $10.00 and part of that should be charity. The panels are expensive enough live to cover costs. Selling live feed is greedy.

[5.31] As well as providing information on prices, some respondents indicated that they might consider alternative business models. Some suggested a flat fee should allow access to a range of videos, a model reminiscent of streaming services such as Netflix. One respondent noted that a similar model was used at Dragon Con in Atlanta in 2016. Others suggested donation or "pay what you can" models, while others queried whether the video would only be available to watch once live or also after the fact, noting that this should affect the price.

[5.32] Although not directly asked whether they thought Creation Entertainment's recent actions had negatively affected the company's reputation, when asked about the relationship between the organization and the fans, 45 percent (44/97) portrayed the relationship as a negative one. Responses included words such as "hostile," "adversarial," "exploitative," and "predatory," and one described them as "vampires." A popular term for the relationship was "strained," which was used by seven respondents.

[5.33] The fandom has built a great community that Creation is taking advantage of. The fans used periscope to spread their joy. Creation is trying to make even more money on it and killing the joy in the process.

[5.34] Creation Ent with all their policies and restrictions has become like an evil we have to deal with.

[5.35] Only 29 percent (28/97) described the relationship in positive terms, and many of these responses still referred to the mercenary tendencies of the company.

6. Discussion

[6.1] It is a common assumption that illicit distribution of video footage from live events negatively affects those who have paid for a ticket by reducing the value of their experience, particularly visible when commercial organizations restrict this practice. However, the results of this study show that for this particular community of Supernatural fans, it is overwhelmingly the case that fans agree that sharing content with others online is of positive benefit and encourages ticket purchase. Not only did fans consider there was value in having access to convention footage but they also thought that access to content from the events increased inclusion and reinforced people's desire to attend them in person. This view was held even by those who attend in person, who in some cases think that it enhances the experience. Evidence suggests online footage boosts interest in the events by raising awareness and increasing fear of missing out in those who have already attended and who want to recreate the experience.

[6.2] Liveness and participation are important; given the option, fans prioritize the experience of being there over others. But realistically, it is not possible for all fans to attend all events, and the community as a whole favors the widening of experience to provide an alternative via technology. This can provide similar feelings of engagement, especially if it is still possible to participate live through experiences that are shared temporally, if not physically. Reason and Lindeloff (2016) note that this investment in temporal specificity is important to create a link between the audience and the performers, and among members of the audience. Evidence from my survey responses suggests that the latter is critical for forming a healthy community:

[6.3] Knowing it's live adds an element of unpredictability—nobody knows what's about to be said, not even those who are there. It's exciting. Enables interaction via social media about what's happening that second.

[6.4] Live videos provide more opportunity for fan interaction which to me is an integral part of this fandom.

[6.5] At the start of the period covered by this case study, it seemed likely that there was a clear opportunity for technology to offer mutual benefit to fans and convention organizers. The fans, while using citizen-sourced methods to appropriate content via theoretically banned practices, were creating value for peers (who wanted to see the video and gained community cohesion through shared experience) and for the commercial provider (by boosting interest in paying for attendance). While there would have been some benefit to simply maintaining the status quo of nonenforcement of a ban on filming, it is not unreasonable to assume that the company saw an opportunity for further revenue by bringing the provision of live streaming in house and charging for access. The comments from survey participants who had concerns about video quality and accessibility suggest that this is a plausible business model, as does the fact that the majority of respondents indicated that a $5 to $10 fee for access to video would be acceptable. Fans do not appear to be averse to the idea of paying for higher-quality video content; indeed, access to video content encourages ticket purchase for on-site attendance.

[6.6] Successful models exist for extension of a previously privileged in-person live experience to the digital space. For example, the National Theatre in the United Kingdom has brought live theatre to global audiences via live streaming to cinema screens. This extremely successful program has been found not only to allow the National Theatre to reach new audiences that would not otherwise be able to attend but also to boost theatre audience numbers (Bakhshi and Whitby 2014). The liveness of the screenings is a critical factor to retaining the nature of the experience. The performances are only broadcast either live or shortly afterward to retain the temporal nature of the experience (Nesta 2011).

[6.7] An alternative business model is demonstrated by musician Amanda Palmer, who has previously used Periscope and has encouraged its use in fans to stream her shows. In 2017, with financial support of Patreon backers who undertake a subscription-based model of funding, she made high-quality live streams of several concerts available free online for her fans:

[6.8] this is also part of the serious inspiring beauty of the patreon. back in the day, if you wanted to film a tour for posterity/youtube (and really film it WELL), you were just going to have to come up with $10–$20k magically, knowing you would never actually make a profit from the content. it's so hard to monetize recorded live content nowadays—even DVDs barely made money, and with youtube, forget it.

and yet.

now i can film amazing shit for posterity and share it with y'all and NOT LOSE MONEY. AND GIVE EVERYBODY ON THE ROAD EXTRA MONEY. it's just…astounding. (Palmer 2017)

[6.9] Despite these extant models demonstrating that commercialization is possible, the manner in which progression from transgressive appropriation to authorized technological inclusion was managed by Creation Entertainment has led to conflict. Negative effect is seen both to the strength of the community (which experienced a loss of cohesion during the Periscope ban that has not yet recovered) and to Creation Entertainment itself. Comments in the survey reflect continuing frustration and dissatisfaction with Creation Entertainment as a company and their policies with regard live streaming, and responses to the launch of StageIt were cautious. Rather than introducing streaming as an additional premium service, or even enforcing the ban on fan-produced content in conjunction with the introduction of a formal service, there was a lack of clear communication and a gap in provision during which fans were being denied access to an existing resource with no commercial alternative. Discussion online in the months after these events has suggested that damage to the community of regular convention attendees occurred during this period, with reduced levels of engagement, enthusiasm, and sense of community compared to at the height of Periscope use. Although this may be affected by other unrelated factors within the community, the Periscope ban appears to be an important turning point. Although it seems unlikely that Creation Entertainment intended this outcome, they clearly did not fully appreciate the community ecosystem and the role that streaming technology played within it. Such complex relationships are a rich area for fan studies research to examine, and the outcomes of such study can provide benefit for commercial organizations who face similar future challenges. Additionally, articulations of value may help fans negotiate such contested spaces.

[6.10] Another critical difference between the service provided by Creation Entertainment using StageIt and the crowdsourced grassroots community version using Periscope is the nature of the interaction it allowed between physical and virtual audiences. This difference was highlighted by fans in their survey responses:

[6.11] The videos are lonely unless you can comment & interact with other viewers, like you can on Periscope.

[6.12] I loved the live Periscopes, the viewers comment & that makes it seem as if you're really attending. Watching by yourself is meh. Fun but I'll watch on my own time.

[6.13] As Webb et al. explain, "The goal of distributed performance is to join performers and audiences in a shared sensory experience through bi-directional connections" (2016, 1). While broadcast media have value themselves, there is a marked difference between a one-way channel of communication and the shared experience enabled by live streaming technologies. This difference comes down to embodiment and feedback, as well as the simulated ability to interact with what is happening remotely:

[6.14] The defining quality of the live at this point is feedback—we accept any situation in which we receive a signal in response to one we have sent out as a live interaction. We have, as Baudrillard suggests, moved decisively from a cultural order characterized by "relations" among things to the digital order characterised by "connections" between things. (Auslander 2006, 197)

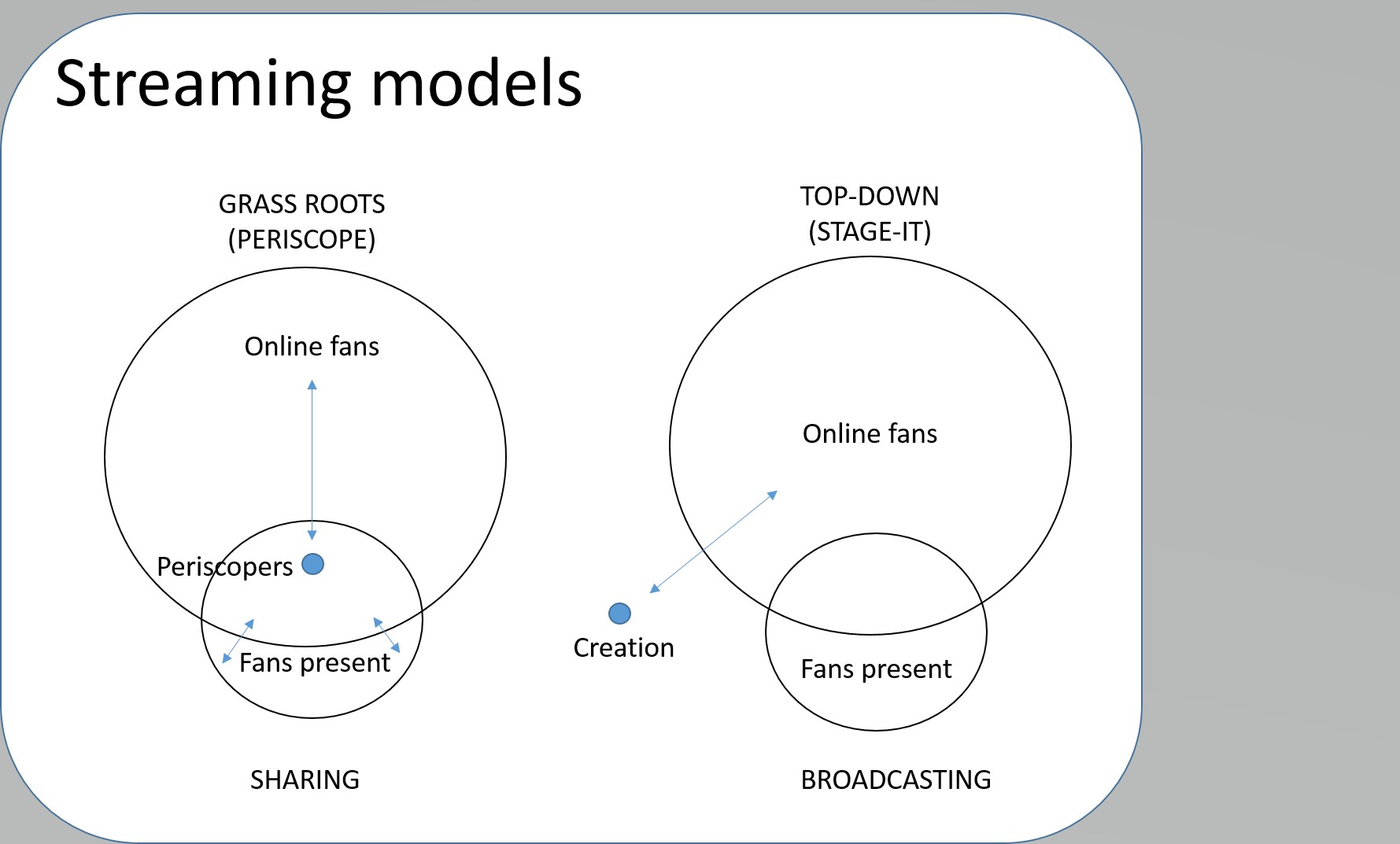

[6.15] As illustrated in figure 6, the two models of streaming in practice at Creation Entertainment Supernatural conventions are distinct in the modes of engagement that fans, both present and remote, can have with each other and the content. With Periscope, the fans responsible for streaming are co-located in the online and off-line spaces, acting as a bridge between both experiences. Those connected within the online community would share the same Periscope experience and be able to communicate with peers and the present fan responsible for the stream in real time. By contrast, StageIt does not allow fans present in the physical space to communicate directly with those watching remotely or vice versa.

Figure 6. Comparison of streaming models.

[6.16] Although the StageIt platform does allow engagement in the form of a concurrent chat room managed by Creation Entertainment, this is not a direct line to fans sharing the live experience; instead, it is a communication method among those watching. Via StageIt, Creation Entertainment acts as a mediator between the online and off-line spaces; Periscope, however, brings these into a cohesive whole. The fan-initiated model prioritizes sharing, whereas the company's model is a more traditional broadcast system. This model is not without value, but conflict has arisen from moving from Periscope to StageIt, resulting in fans being denied the sharing experience that had become commonplace and that had performed the key function of maintaining community cohesion.

7. Conclusions

[7.1] The findings here echo those from previous work examining the positive effects of live streaming on live audience attendance. As online and off-line spaces blur and compress, the difference between participating remotely and in person is less concrete. Distinctions remain, but both modes interact and contribute to the wider fan experience. Digital tools provide new avenues for fandom engagement and community building, and there are avenues for commercial revenue generation by these platforms that do not negate the fan experience. However, there are complex interactions between the technology, the online community, and the off-line experience. These must be carefully and cautiously managed to avoid alienating the community or losing key features that are the basis of the success.

[7.2] Future use of these technologies both by fans and commercial producers should not disregard potential opportunities for increased profitability and fan positivity, but they should take care during monetization. The power dynamics inherent in the encouragement or prohibition of such services are critical, and the nature of sharing versus broadcasting must be considered. A successful model must be inclusive; this is particularly important if existing fan practices through appropriation of technology will be affected by the introduction of commercial alternatives. Fans are not averse to paid models if value, mutual respect, and engagement are built into the approach.

[7.3] Questions still remain over the nature of such private footage when it is released online, as well as aspects of ownership and reuse. Future exploration of the nature of digital public spaces must address these ownership questions, as well as who benefits and who is affected by previously transient, restricted experiences being recorded and shared in a permanent record. As fan communities become more embedded in the rapidly evolving hybrid physical/digital world, the future of sharing technology necessarily affects the future of fandom.