1. Introduction

[1.1] I have no data yet. It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, "A Scandal in Bohemia" (1891)

[1.2] In this analysis of the relation between a social media platform's infrastructure and the creation of a fandom eschatology, we attempt to understand how the functionality of Tumblr supported the development of The JohnLock Conspiracy (TJLC), a fandom of the BBC TV series Sherlock (2010–17), as a fandom eschatology. We explore fandom's radical groups through the lens of a secular eschatology in order to understand why and how these groups emerge within fandom, and thrive or collapse when the end result of their beliefs fails to materialize.

[1.3] In Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga ([1939] 1949) explains how play is conducted within a magic circle, which is set apart from real life. While within this magic circle, the players must play by the game's rules, which must be taken seriously or else the game would fall apart. Fandom can be likened to this magic circle: within in, fans develop serious analyses of TV shows, engage in meta, and create fan art. Yet for some fans, it stays serious even outside the magic circle. While what follows will focus on a specific group dynamic on a specific platform, fandom wank, policing, and antifans have been present ever since fans organized into groups. Indeed, Bacon-Smith (1992) shows how fanzine editors acted as gatekeepers, with their perceptions of what made good fan fiction crucial for its publication in the first place. Even after the hard-copy fanzine era that Bacon-Smith describes in her ethnography, fans continued in this gatekeeping role, with, for example, fans maintaining online lists in which they decided what was worth mentioning.

[1.4] With inclusion comes exclusion, and through the years fandoms have had their share of wars and upheavals (https://fanlore.org/wiki/The_Blake%27s_7_Wars; https://fanlore.org/wiki/Ship_War; https://fanlore.org/wiki/CrystalWank). Inevitably, infighting occurs between groups—infighting that evokes the seriousness of religious believers rather than supposedly fun-loving creators of fan works. We understand TJLC as a version of secularized eschatology—secularized because TJLC is not a religion, yet the actions of its proponents express characteristics of forms of eschatology common to many religions. Eschatology denotes events that lie in the future; it may signify "the last days" or "the end of days," much like religious eschatology may focus on an upcoming apocalypse, as Christianity does (Collins 1999b, viii; see also Collins 1999a).

[1.5] With secularization increasing after the Enlightenment, eschatology gradually became decoupled from specific religious contexts. Instead it came to signify any thinking about the future and anticipating an end within this future. In the twentieth century, it also found its way into more secular and popular contexts, like the Doomsday Clock; it also appeared in films depicting the end of the world, like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) or the aptly named Armageddon (1998) (O'Leary 2000). Although eschatology has come to encompass both religious and nonreligious contexts, here we refer to eschatology as a way of thinking about the future that anticipates an inevitable end.

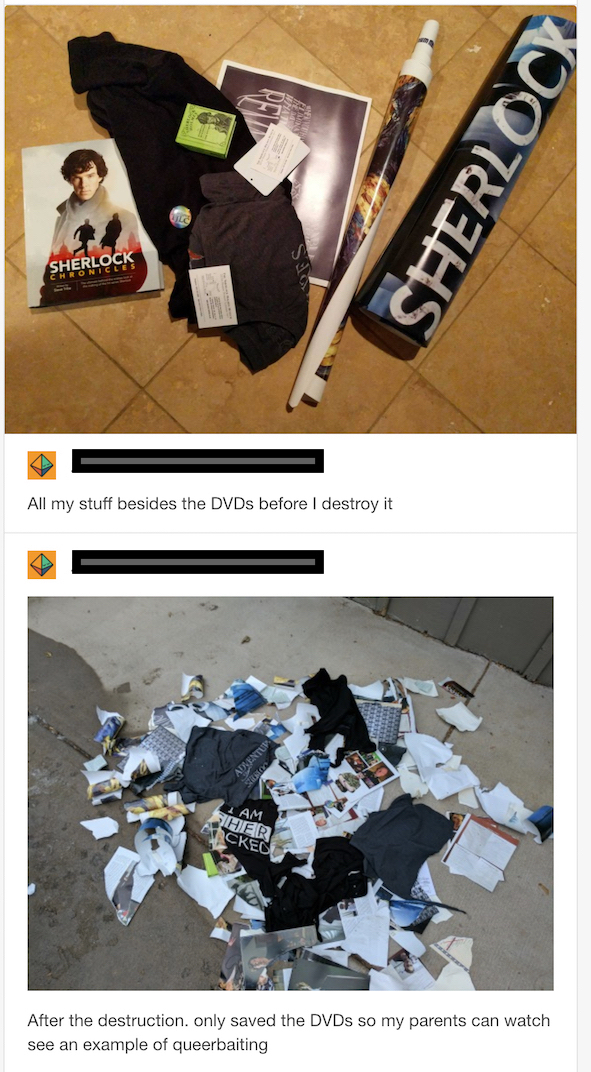

[1.6] The case of TJLC as a secular eschatology relies on the group's belief regarding what must inevitably happen at the end of the program: John Watson and Sherlock Holmes (JohnLock) must get together romantically. While explaining and developing this belief, fans create meaning and control, both within the canonical text—Sherlock—and within the problems and challenges users face in on- and off-line worlds. When the final episode of the series, 4.03 "The Final Problem," aired on January 15, 2017, fans found the ending ambiguous. Some were convinced that the pairing was upheld; others were convinced that such a pairing was forever closed off. Reactions to the final episode ranged from disbelief that it was in fact the final episode (https://fanlore.org/wiki/The_JohnLock_Conspiracy) to the physical destruction of Sherlock merchandise (figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshot, January 16, 2017, of a now-deleted Tumblr account showing Sherlock memorabilia before (top) and after (bottom) its destruction.

[1.7] In what follows, we provide an overview of TJLC and then argue for the need to broaden our understanding of groups like TJLC. We also acknowledge the harm groups like TJLC cause within fandom, as well as the harm inflicted on members of TJLC by other fans.

2. Methods

[2.1] Here we use an autoethnographic approach, which provides a deep understanding of the processes and events unfolding in fandom, to collect data and try to understand the do's and don'ts of fandom (Ellis 2004). We collected data from the Archive of Our Own (AO3; https://archiveofourown.org/), from our own Tumblr blogs, and from various online fandom sources. We acknowledge the limitation of being unable to research the whole of TJLC. Instead, we tried to follow relevant threads, although of course other users or posts might have had a larger impact than the ones we found and describe here. Neither of us engaged in online discussions except for a few reblogs and likes. Lurking on the internet is one of the ways that researchers can examine their subject without its being affected. While Tumblr makes lurking easy, and much of the data can be collected from what seems like public places, trespassing is still an ethical research issue. We did not directly approach fans considered as being at the center of TJLC because outing ourselves as researchers would have put us in a direct line of attack, leading to possible personal repercussions. However, we made the fans we talked to aware of our research.

3. The JohnLock Conspiracy

[3.1] In 2010, BBC One aired the first episode of Sherlock, a modernization of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's detective tales about Sherlock Holmes. Starring actors Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock Holmes and Martin Freeman as John Watson, the series became an instant hit. Only three episodes per season were released, and as of September 2017, the series comprises four seasons plus one special and a mini episode. The ratings for Sherlock indicate a clear decline, from a Rotten Tomatoes 100 percent positive rating for the first season to 55 percent for the final episode of season 4.

[3.2] When 4.03 "The Final Problem" aired, members of TJLC were convinced that John and Sherlock would kiss. When the episode concluded without any kiss, TJLC began discussing the possibility—nay, the actuality—of a fourth yet-unaired secret episode, which would canonize JohnLock. This idea became so established that many fans watched the BBC miniseries Apple Tree Yard (2017), which aired on Sunday, January 22, 2017, a week after the last Sherlock episode. The consensus of these fans was that the BBC would broadcast only a few minutes of the this alleged show; then the character of Moriarty would interfere, and the real final episode of Sherlock would be shown instead (Lewis 2017; O'Connor 2017). Alas, Apple Tree Yard was indeed another show. Despite this blow, TJLCers began discussing when the actual final episode would air, interpreting as signs of the upcoming event the numbers and dates given in canon and in interviews by producers, writers, and actors. As of this writing, however, this alleged secret final episode has not aired.

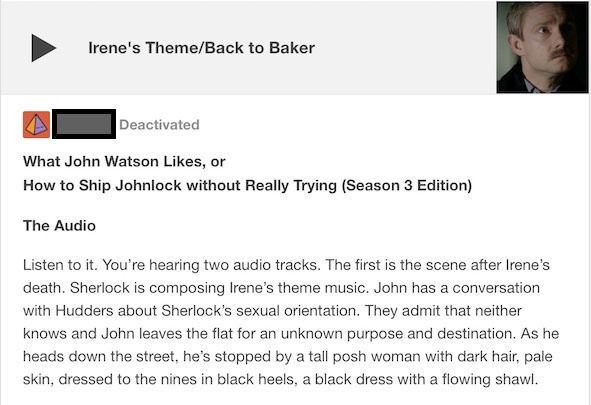

[3.3] One impetus for TJLC came from a post by AB (name anonymized), posted on January 26, 2014, entitled "What John Watson Likes, or How to Ship JohnLock without Really Trying" (figure 2).

Figure 2. Screenshot of the first part of AB's "What John Watson Likes, or How to Ship JohnLock without Really Trying," January 26, 2014, which became part of the initial foundation of The JohnLock Conspiracy.

[3.4] AB later stated that the post was thought of as a game, not to be taken seriously. Still, the basic idea of the post—the perception of the various hints and interactions between John and Sherlock in the series, found fertile ground among a group of JohnLockers, who coined the term The JohnLock Conspiracy. In a later post, AB wrote about how the idea of the death of the author was meant as a mode of distancing from the conspiracy (figure 3). AB eventually deactivated the blog in 2017 to avoid further hate and aggression from TJLC community.

Figure 3. Screenshot of part of AB's post regarding the death of the author, June 10, 2014. "Mofftiss" is the portmanteau for Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, the writers of Sherlock.

[3.5] The notion of "TJLC—The JohnLock Conspiracy" was coined a few hours after the first broadcast of 3.03 "The Sign of Three." Already meta had been written regarding the possibility of JohnLock, but from then on, TJLCers meticulously analyzed every detail and scene, every shrug of Moffat or pause from Gatiss. The meta showed a profound knowledge of a variety of areas—music, color symbolism, cinematography, mathematics. Absolutely everything was examined to find hidden leads. Gestures, dialogue, clothes, camera angles, wallpaper, books, and soundtrack were scrutinized. Nothing was too small or too big; everything found equal consideration. The hope that Moffat and Gatiss were following a sophisticated and secret already laid-out plan became a certainty. Analysis and interpretation of the available material was turned into proof of JohnLock.

[3.6] Conspiracies like TJLC take their point of departure the possible development of future texts. As such, it has the aura of a soothsayer trying to convince his followers that he alone can predict what will happen—or, as a secular eschatological approach shows, it becomes a belief in a future outcome. The conspiracy exists in the mind of the fan group because they are convinced that the producers and writers of the show know the endgame—in this case, JohnLock. Once the fans have deduced the result, these same fans have to accept that the producers will keep this a secret until the big reveal. Yet this is the crux of the problem. When interpreting future texts—and through it the development, or its lack, of characters and their relationships—outspoken members of the conspiracy group analyze existing texts and thereby describe, via elaborate explanations and proof, the certain future that is to come. Certainly this is a worthwhile reading of the text, and many fans engage in it, trying to find hints of future development for the beloved possible pairing, or just playing around with imaginative ideas to be used in fan fiction or fan works.

[3.7] Problems arise once these ideas are taken as the truth, when one group of fans starts to divide fans into believers and unbelievers, into those who are right thinking and those who should be persecuted and shamed for their perceived disbelief. These groups find common ground in their spreading of the one true belief and in their fierce fighting of anybody who opposes them. Anything that may be used as to support and confirm the theory will be applied, and anything contradicting it will be ignored, dismissed as a lie, or attacked. If the producers or actors involved in the show deny the conspiracy, then the fan group will accuse them of lying or hiding something. As our research showed, sometimes it could be difficult to prove a certain remark made by the writers. For example, Gatiss (2016) directly accused the press of quoting him incorrectly regarding the idea of JohnLock, and Moffat notes, "It is infuriating frankly, to be talking about a serious subject and to have Twitter run around and say oh that means Sherlock is gay. Very explicitly it does not" (Parker 2016). Contradictions like this fuel the belief of a conspiracy.

[3.8] Another problem arises through the way fans choose to view the canonical text. The scholastic fallacy (Bourdieu 2000, 49–84) may be found in the academic idea of contemplation and reason when thinking about the world and its inhabitants. As Bourdieu reminds us, everyday life is nothing like that. TJLC meta and discussions show exactly this kind of fallacy. Fans seem to believe that every little sign in Sherlock has a deeper meaning and must be interpreted within the rubric of an inevitable JohnLock pairing. Despite the writers' repeated explanations of how they concocted ideas on the go and developed plot points within the series on a whim, TJLCers stood their ground, claiming that everything shows the endgame to be JohnLock.

4. TJLC as a group

[4.1] In understanding TJLC as a group, we follow Noyes's (1995) suggestion that the notion of a group is shorthand for a dialogue between an "empirical network of interactions in which a culture is created and moves, and the community of social imaginary that occasionally emerges in practice" (452). The network of interactions is in our case made up of the actual exchanges taking place on and mediated by the functionality that Tumblr uses to facilitate dialogue. The social imaginary is in our case a secularized eschatology. We follow Taylor (2007) in understanding a social imaginary not as a set of ideas but rather as what it enables: making sense by studying the practices of a group.

[4.2] The practices of TJLC are in alignment with the notion of authorial intent being clearly stated in the text. In this, TJLC differs from practices of transformative fandom in which the author is dead, as stated by AB in figure 3. Defining TJLC by using existing fandom terms turns out to be challenging. Because TJLC is perceived as disruptive and aggressive by other fans, the terms "antifan" or "nonfan" come to mind.

[4.3] The definition of antifans has changed through the years, coming to refer to different kinds of fan groups or nonfans who in some way are opposed to the canonical text, other fan groups, or certain kind of ships. When Gray coined the term in 2003, the antifan was defined as a fan who strongly disliked the original text. The term "antifan" has since been expanded to fans who could be defined as "inverse loving critics" (Duffett 2016, 48), meaning fans of a given text complaining about the same for not meeting expectations. Although this sounds close to a definition of TJLC (complaining about the lack of JohnLock), it is still a misleading characterization. TJLC is about interpreting the text, and thus accepting the original TV series, but it is also about understanding the text as a sign indicating what is to come. As such, there is no complaining about how the TV series as such is developing; rather, there is a need to further interpret and deduce when and how the "real" endgame will play out. Any complaining about the series would actually be a contradiction to the belief in TJLC because the series itself lays the ground for the belief.

[4.4] Antifans should instead be seen as groups of fans fighting for discursive dominance and struggling to reach consensus about how a given text should be interpreted. Through this ongoing discussion, fans are able to construct competing truths about the series (Johnson 2007, 286). Hills (2002) talks about the "endlessly deferred narrative" and "hyperdiegesis" to show how a given, finite text can be retold and reinterpreted within fandom spaces (131). These discussions can create great chasms between fan groups because "fans do not easily agree to disagree" (Johnson 2007, 288). This is further enhanced with regard to TJLC because the group sees the text as the ultimate truth, with only one given result possible: JohnLock. Any fans disagreeing with or doubting this result would have to be convinced of the rightness of TJLC or be ostracized.

[4.5] Although we see TJLC as a secular eschatology, it differs from Hills's notion of a cult (2002, 131–71). According to Hills, a cult is dependent on the text to be interpreted and speculated about. For TJLC, there is no speculation regarding the certain outcome of the text. Everything must be interpreted and discussed with an eye to the endgame: JohnLock. This is only possible through the development of a clear belief system that enables all members to see themselves as true believers—or that permits fans to point out nonbelievers.

[4.6] TJLC might have different motivations than trolls, but because of the group's strong belief in a certain outcome of the text, their behavior in Sherlock fandoms creates fear and anger, resulting in what might be described as shouting matches, which are destructive to the discourse and the creation of fan works. Many fans have left Sherlock fandom, citing TJLC as the cause. Fans who write posts discussing or providing meta on JohnLock are reluctant to tag them accordingly, afraid of being drawn into an argument and becoming a target. This goes for both die-hard TJLCers and fans who oppose the idea of the canon endgame being JohnLock.

[4.7] TJLC cannot be explained solely by using the existing definitions of antifans, particularly because TJLC cannot be defined as antifandom because everyone agrees on the canonical text. Only the repercussions of TJLC within fandom discourse have similarities with antifans; TJLC can be seen as a deeply felt wish for representation and change. As we argue next, TJLCers are more akin to secularized eschatologists.

5. TJLC as secularized eschatology

[5.1] What does a secularized eschatology regarding an understanding of TJLC and the aftermath of series 4 of Sherlock entail? The notion of a secularized eschatology comprises two parts. The first is interpreting the idea of secularization and its place in Western history, a transition that occurred from a world where God was central in everyday life five hundred years ago to a world where God is dead in the everyday public space (Taylor 2007). The other is interpreting particular instances of the development of secularization and how these articulate or rearticulate eschatological elements—that is, knowledge of what will come, perhaps with a religious aspect but in a nonreligious setting (for modern biology as an example, see Nyhart 2009).

[5.2] The presentation of a history of secularization and eschatology is outside the scope of this essay; we refer readers to Taylor (2007). Here we limit ourselves to some relevant aspects of eschatology while interpreting it in relation to TJLC. Eschatology contains four key notions, which we use as a heuristic in interpreting TJLC: a question about purpose, plan, or teleology; whether apocalyptic aspects are involved; whether it contains considerations of parousia (Greek for "being present"); and what kind of time, linear or cyclical, is presupposed. These key notions underpin TJLC as a fandom phenomenon, especially as a particular instance of secular eschatology, which we take as a defining feature, thus differentiating TJLC from other fandom phenomena like antifans, social justice warriors, or cult fandom.

[5.3] Defining the eschatological as containing an inevitable future end is claiming something teleological about it—that eschatology involves a final end or cause. But in what sense? If we look at how TJLC pictured the coming event of John and Sherlock getting together, it is presented as a final end (the final episode) containing a radical transformation of one form of existence to another (John and Sherlock finally expressing their true love). However, teleology in and of itself does not necessitate an absolute final end. Indeed, we can readily picture an eternal universe made up of all kinds of plans and causes; let us call this an unbounded teleology. Unlike the abruptness and transcendent character of the event of eschatology, teleology is often connected with some gradual, perhaps even immanent process. Furthermore, in teleology we can trace a rational explanation (Okrent 2007), whereas in eschatology faith is important. Within the perspective of TJLC, certain signs indicate the coming event of John and Sherlock revealing their true relationship, but only if the fan believes beforehand that this event actually will happen. The case of TJLC is more of a bounded teleology: there is a final end and a transcendent plan laid out for getting to this end, and faith or believing in this end is what upholds TJLC in light of the failure of certain events to materialize (such as the interpretation of a Moriarty-interrupted showing of Apple Tree Yard).

[5.4] The word "apocalyptic" is derived from the Greek word apokalypsis, meaning revelation in the sense that a god has revealed the end of something, perhaps the ongoing struggle between good and evil, as in the Book of Revelation (Collins 1999b, viii). What is interesting here is the function of apocalypticism, which Collins (1999a, 158), following David Hellholm, states is intended for a group in crisis with the purpose of exhortation and/or consolation by divine authority. Hence, as Idel (2000) claims, apocalyptic aspects of texts present us with an "unveiling of a collapsing reality" (204), as well as a projected hope for repairing this reality: "the 'collapsing' vision of reality is never detached from its more positive sequel dealing with the dramatic improvement that follows the collapse of the older order" (205). Apocalyptic aspects of texts are influenced by social concerns or problematics of the groups producing these texts, using their imagination to solve these problematics by projection of this solution into the future—that is, hoping a new and better order will replace the old, collapsed one.

[5.5] In TJLC, there is a social concern of the fandom reflecting a collapse of the old order between Sherlock and John, which reflects a wider social order in which Sherlock and John, as a result of societal norms, are not allowed to show their love for each other, as well as the projection of the installment of a new order into the immediate future. These secular revelations are made up of what the producers of the series reveal regarding coming episodes, which is interpreted by TJLC fandom—alongside the already shown episodes—as signs of what will inevitably happen. However, "apocalyptic hope is invariably hope deferred" (Collins 1999a, 159). This is exemplified in TJLC, with the failure of the realization of what was imagined to be inevitable. As the new order fails to materialize, TJLC seeks to uphold the imagined future-to-be by reinterpreting the failure as a nonfailure and as a new sign of what will inevitably happen. Thus, the promise of an inevitable future is upheld. This is exemplified by fans claiming that the upcoming Apple Tree Yard TV miniseries would in fact be the fourth, real, and final Sherlock episode. After this failed to be the case, fans began speculating about upcoming events and important dates within canon and fanon, such as birthdays and anniversaries, to discover the actual air date of the supposed missing episode.

[5.6] This process of interpreting events and signs as revealing the presence of something absent, an event about to happen, is connected to parousia, a term literally denoting the arrival of a king or emperor. In Latin, the word is advent, a term now used within Christianity to signal the coming of Christmas. In its Christian theological use, parousia denotes the Second Coming of Christ; it is also tied to the psychological experiences of anxiety, doubt, and searching for certainty within the realization of what is absent—in this case, Christ's return (McGinn 2000, 373). Heidegger ([1920–21] 2004) performs a reading of what is specific for the Christian concept of parousia, which can function as a frame for understanding the concept's applicability in relation to TJLC.

[5.7] Heidegger ([1920–21] 2004) starts out by noting what is distinctive about the Christian sense of parousia: not just the arrival of the Lord or Messiah, as in the Old Testament or Judaism, but the "appearing again of the already appeared Messiah" (71). This, he claims, changes what he terms the factual experience of the Christians (a precursor for his notion of facticity in Being and Time [1927]), because the structure of the Christian hope is different from a pure expectation of a future event. Rather, Heidegger claims, for Christians, the Second Coming of Christ cannot be grasped and answered using an objective and linear sense of time in which the this event is predictable. Instead, the knowledge of the when "must be of one's own." It must be anchored in the factual experience of the Christians. Heidegger therefore claims that what parousia does is referring Christians "back to themselves and to the knowledge that they have as those who have become" (72). The Second Coming of Christ is an event in the future, but its real meaning lies in the enactment of the previous life of Christians themselves in light of what they have become. Thus, there is a complicated relationship between presence and absence in the notion of parousia. Because one is incapable of delineating when, detecting traces in the present of what is absent becomes important. Heidegger cites the letter of Paul to the Thessalonians that "the day of the Lord comes like a thief in the night" (79, referring to 1 Thessalonians 5:2), implying that these traces come unanticipated or suddenly. Furthermore, being able to see the traces as traces when they appear is equally important because this defines Christians and their understanding of parousia in comparison to other understandings of parousia.

[5.8] Similarly, TJLC requires the same effort in detecting in the present traces of the absent though the inevitable coming. Whatever traces are laid out, they could not be anticipated. Rather, they are related to the factual experience of TJLC—how they enact it by interpreting it as pointing toward JohnLock as the endgame. TJLC at first seems like presupposing an objective sense of time because the endgame—the when of the kiss—is predictable, as it will occur in a particular episode (the series finale). However, the failure of the endgame to take place is an event that, like in the Christian sense, refers back to TJLC participants themselves. If Heidegger's interpretation of the Christians as "those who have become" is correct, then it means that they have a history—namely their experience of the First Coming of Christ—that facilitates the enactment in their present life. TJLC, however, has no tradition or history to turn to, thus enabling TJLCers to interpret their lives in terms of what they have become, in much the same way as the Christians. This gives us a clue for interpreting time, with a common destiny in mind as the endgame.

[5.9] Relatedly, an analysis is required of what conception of time is presupposed. Heidegger argued against using an objectivist conception of time because such a conception is incapable of understanding temporality as it unfolds in the factual existence of humans. Instead, parousia reveals a complex relation between future and past in the present, which resembles neither a cyclical nor a linear conception of time (Gallois 2007). The case of TJLC, however, hints at a subjective conception of linear time. TJLCers are united not by a common background but by a common destiny: the shared belief in the endgame's inevitability. As Cassirer (1961, 290) notes, if the development of history is conceived as already laid out in advance—that is, what will happen, must happen, as in TJLC—then this implies two kinds of fatalism. First, the road to the endgame is already laid out, and TJLCers cannot affect it. Here destiny is passive and inexorable; no matter what TJLCers do, the endgame will take place, and all the signs show it, with the canonical text demonstrating hidden leads that need only be correctly interpreted. Second, after the failure of the final episode to result in the desired outcome, the sense of destiny becomes more active and irrevocable. The shared belief now turns on demanding the endgame to happen: the final episode is supposedly already made, and the producers are keeping it from the fans. This reflects linear time: the endgame will inevitably happen, so TJLCers keep pushing the event forward by interpreting what happens in light of this inevitability. As Esposito (2010) notes, "Only by repeating that beginning [inizio] will the community with a destiny be up to the task that awaits it" (100). Esposito is referring here to Heidegger describing this repetition: "The beginning is still here. It isn't behind us, like an event that happened long ago, but lies in front of us…The beginning…calls us to reconquer once again its greatness" (100). The temporality of TJLC resembles this repetition of the beginning of John and Sherlock's love story, the culmination of which (its overt acknowledgment) continues to lie ahead, and the inevitability of which is assured again and again by interpreting the signs pointing to it. Indeed, the very ending of 4.03 "The Final Problem" is described as a beginning—as the actual start of what we know as Sherlock Holmes (Bone 2017).

[5.10] To reiterate, we propose that TJLC can be understood as an example of secular eschatology. This is characterized first by a bounded teleology involving a final end and a transcendent plan laid out for arriving at this end. Furthermore, faith in this end and the existence of a plan to bring it about uphold TJLC in light of the failure of the significant event to materialize. Second, TJLC contains apocalyptic elements reflecting a collapse of or a problematic within an old imagined order, here between Sherlock and John, and the imagination and projection of a new and better order replacing the old collapsed one. Third, though this new order to come is absent, it is interpreted through different present signs that indicate what is to come. Finally, the sense of time relies on subjective linearity, in which a new beginning is continuously claimed to be what is to come.

6. Tumblr's infrastructure

[6.1] TJLC has its origin and development on the social media platform of Tumblr. Although fandom wank and infighting have long been a hallmark of the fan experience, the infrastructure, gratification system, and functionality of Tumblr can be partly blamed for the unrestricted expansion of TJLC within Sherlock fandom. To analyze Tumblr's infrastructure, we use the following main topics: functionality (What can I do? What does it do?), interaction among users (What can I do with whom?), and site and content navigation (Where am I in relation to the whole? What are the boundaries to this domain?) (Jensen 2017). Different kinds of online culture and behavior result from the responses to these questions.

[6.2] Platforms such as LiveJournal (LJ), Dreamwidth (DW), and Reddit enable groups to create and share content. Each group has one or more administrators, who can set a number of rules for the interaction within the particular group. LJ and DW have fandom groups dedicated to fandom wank that demand anonymity from users (e.g., https://fail-fandomanon.dreamwidth.org/). However, even within these groups, certain behaviors and rules must be followed. It is seen as bad conduct to link or tag hate, meaning that wank about a fan should be conducted without said fan being aware of it. While this might seem like an ethical problem, it gives fans the possibility of avoiding hate, while other fans can use these sites to release their anger and frustration.

[6.3] Tumblr, however, has no possibility to create a place within which a group can identify itself and its members the way LJ, DW, or Reddit do. Users can create discussions in an entirely closed, password-protected Tumblr group, but this is not how Tumblr is meant to work because posts from these closed sites are not visible on members' timeline, the dashboard (or dash). Instead, Tumblr is an open platform, which provides few tools for users to create a safe space on their blogs. For example, user A may block user B to avoid seeing any of user B's posts on user A's dash. By blocking user B, A's posts are no longer directly visible for B, and user A will no longer see any of user B's posts on user A's dash. User B, however, will still be able to see user A's posts, and can like and reblog them, if a post from user A is reblogged by user C, who is connected to both users A and B without being blocked by any of them. User A will receive a notification of the activity; that is, despite blocking user B, user A may be able to see user B's comments and tags via user C.

[6.4] Tagging, a method used to find and archive relevant posts, is another way to try and avoid unwanted attention, or to avoid seeing posts that might be triggering or offensive. Tagging on Tumblr is useful for user A to avoid seeing unwanted content, provided other users remember to tag said content. But any other user is able to visit user A's blog and comment or reblog from user A's blog. Although user A might stay away from the TJLC tag, nothing prevents a TJLCer from going to user A's blog and using it in their discussions. What was intended as an ironic comment on BBC's Sherlock could morph in to an aggressive explanation of why JohnLock has to become canon—an example of bounded teleology. Because every reblog creates a copy of the original post, several discussions and understandings of the original post can be ongoing in parallel on various sites that have duplicated a post. Users can delete or edit a post, but copies reblogged from the unedited original will remain.

[6.5] The functionality of Tumblr has changed and will continue to change; perhaps future changes will enable users to create a safe environment for their fan works and fan discussions. However, currently, the fast-changing dash, and the way reblogs and likes are distributed fuel heated discussions among users of different opinions. Although each reblogged post can initiate a new string of explanations and discussions, only one user is notified of all the actions regarding the original post: the original poster. A reblogger will only receive direct notifications of any actions on the reblogged post from the first subsequent user. That is, user B reblogs user A's post X and comments on it. User C likes and reblogs post X from user B; notifications of both actions are sent to users A and B. User D likes and reblogs post X from user C; notifications are sent to user A and user C. User B will not receive a notification of user D's potential comments. If user B wants to follow the discussion, the user would have to check the notifications of the post itself. Even so, however, it can be difficult to see how the discussion progresses and who reacts to what statement. Comments are not threaded, with the original statement followed by the first reply, second reply, and so on. Instead, comments, likes, and reblogs are shown in a timeline without showing the actual time, thus hiding the nuances of discussions taking place in actual time. In the newest Tumblr design (July 2017), comments are shown separately, without any indication of their inherent relationship.

[6.6] Tumblr's interactive design therefore has content at its center. Enabling easy access to the site, easy posting, reblogging, commenting, and liking are of the highest importance. The main drawback is the lack of groups, which could permit training new members in fannish norms, as well as creating a space providing a modicum of safety for its members. Furthermore, the idea of belonging to a group is difficult to maintain on Tumblr because the individual blogs and users can change their content or intention without warning. While this allows for diversification, it can also leave users feeling isolated and unsure whom they are interacting with. In the wake of TJLC, a few abandoned blogs were hijacked by other users, who would post hate and the like using the former users' blog names—hijacked in the sense that anyone can claim a deactivated blog name and continue blogging under that name. While the blog has to gather new followers, users are accustomed to glitches in the form of a sudden unfollowing thanks to Tumblr's known technical problems. This means that the new owner of a former well-established blog can spread hate and misinformation without any repercussions.

[6.7] Tumblr's infrastructure cannot in and of itself account for the eventual impact of TJLC. Still, the obvious differences between Tumblr and older fandom platforms such as LJ and DW might account for the sense of insecurity in Sherlock fandom during the height of TJLC. "Staying in your lane" or "not going into the tags" only works if there is a possibility to set boundaries and enforce them. None of that is present within the current functionality of Tumblr. Tumblr does not support the creation of a place where members have to follow a set of rules. No administration or enforcement of rules is possible. Tumblr remains an open space in which a post is posted and reblogged; the creator of the post loses control with each subsequent use and interpretation of the post, even if the original post is deleted or the blog is deactivated. The impact on the users is twofold: they cannot create boundaries to ensure a safe experience on Tumblr, and they may become isolated in their fandom experience. All of this enables the success of TJLC as an eschatology: a belief system like TJLC makes it possible to belong to a group, to feel like a member of something bigger than oneself. By creating and using the #tjlc hashtag, a Tumblr user becomes part of an ephemeral community, not designated by an actual place (Christensen 2017), however abstract digital spaces might be, but by a common interpretation of Sherlock.

[6.8] Because of the lack of a safe place in which to become a group, TJLC needs radicalization to ensure a clear idea of what membership entails. It is not enough to become a follower of a certain blog or to use the #tjlc hashtag. Reblogs, likes, meta, and interpretation have to be in line with supporting the endgame: JohnLock. Tumblr is here a space in which groups try to define a separate and safe place of their own by using the #tjlc hashtag. This hashtag, however, only functions on the social imaginary level because the space mediated by Tumblr will never allow a group to define and delimit its own place and identity in a meaningful way. Groups therefore revert to the social imaginary mode, here manifested by secular eschatology, to perform group identity.

7. Conclusion

[7.1] TJLC has for years been blamed for many transgressions within Sherlock fandom, including doxxing, harassing, and bullying other fans on- and off-line. However, explaining the behavior of TJLCers as antifans is not helpful in understanding this particular fandom phenomenon. TJLC evolved through the particularity of Tumblr's platform. It is not inclusive and diverse, and it is not based on the idea of a better world. Rather, it is exclusive: in TJLC, fans do not embrace diversity or criticism but rather enforce a certain kind of singularity. During the height of TJLC, just before the airing of the last episode in 2017 of Sherlock, both sides escalated their fight. On one side were TJLCers who wanted be able to say, "Look! We told you so! JohnLock is canon!" On the other side were TJLCers who wanted to be able to point out how stupid TJLC had been in the first place.

[7.2] Fans create and participate because they are emotionally involved in a media event. The media event is transformed into a meaning-making endeavor. Embracing the idea of TJLC, becoming a member of a clearly delineated group on a platform like Tumblr, is one way of dealing with emotional affect when engaged in fandom. However, as we have noted above, Tumblr can be a confusing and dangerous place to practice fandom. Although users can employ tags to obtain information on new fan works as well as categorize their own, the feeling of belonging to a group is only manifest when users manage to engage personally with other fans, which means fan engagement is necessary to create a sense of commonality. One way of doing this is engaging in TJLC.

[7.3] However, several elements must come together to create the perfect storm that is TJLC: a platform that has content, not users, at its center, and that includes an interactive design unique in fandom because it does not support group formation, user administration, or enforcement of rules in a particular space; an original text that hints at a larger idea hidden behind the visible part of canon; and a fandom that is able to engage with and is knowledgeable about the original canonical text. Although we see TJLC as a fandom (or antifandom) created by Tumblr functionality, fandom eschatology provides a useful lens through which to examine highly directed fandoms that do not support user-controlled spaces and posting. Fandom eschatology acknowledges the seriousness that characterizes the work and efforts of the fans involved.