1. Introduction

[1.1] This article explores similarities of practice in collecting and compiling in the romantic era and the digital present of the twenty-first century, identifying the similarities between the form and content of Tumblr, and the commonplace books and scrapbooks of the past. Both the online platform and the paper page enable users to collate and share content. The practices of Anglo-American fannish compilation have changed very little since the late eighteenth century; examples include the addition of a favorite line from a text to a chosen image, or the rewriting of key words in a text to make it more relevant to the owner of the page on which it appears. As Jessalynn Keller has established, girls' blogging is "part of a lengthy tradition of girl's media production…such as zine-making, consciousness-raising, and media production such as Ms. Magazine" (2016, 2). Keller establishes these twentieth-century practices within the framework of a recognized feminist movement, exploring the use of these tools for publicly engaged activism. Here I seek to explore not the political intentions of the blogger and commonplacer but rather the mode they choose to communicate. The textual response practices familiar to both contemporary Western media fan spaces, and to romantic-era customs in the construction of the sentiment album, such as collage, demonstrate an impetus to subvert or transcend the originary meaning of the texts. These practices clearly echo Claude Lévi-Strauss's idea of bricolage in constructing meaning. I explore the notion of the fan as bricoleur, working with mainstream cultural signs and signifiers to produce new meanings and possibilities for representation. The materials available to the compiler change as fashions in art and media technologies develop; however, the practices of combining and recombining these changing elements remains remarkably consistent. The continuation of the same practices across two centuries speaks to their effectiveness in drawing out subsidiary themes from cultural texts. That the bricoleur communities still seem to be predominately composed of marginalized people—such as young women and queer-identifying people—and are often culturally positioned as focused on romantic interests and sexuality, suggests that many of the same exclusionary hierarchies of cultural value are still in play. The production and dissemination of narrative fiction is still dominated by men, and still foregrounds masculinist perspectives and content that does not reflect the desires of the margins.

[1.2] Discussions regarding these practices from outside the audience and community in which the compiled works are originally shared and created are consistent in their critical tone. The idea that the original text is being misread, or devalued, is often put forward and the criticism is also often highly gendered, assuming female identity for the fan, or assigning femininity to compilation methods. Tumblr is viewed as an online platform predominated by, and aimed at, young women. The sentiment album of the romantic era was similarly culturally coded, even though this perception is not entirely borne out by evidence (Duggan and Brenner 2013). Pejorative online terminology such as "Tumblrina" demonstrates this perceived femininity that is repeated by authors writing about social networks and online platforms; critics like Angela Nagle call Tumblr "more feminine," as compared to sites such as Reddit and 4chan (2017, 19). Further, young women's skills as negotiators of online space are perceived as being less developed when compared to male contemporaries, even by women themselves, though this is not supported by evidence (Hargittai and Shafer 2006). As outlined in the next section, similar divisions were imagined between a "masculine" tradition of commonplacing and the development of "feminine" sentiment albums. Whether the creator of the transformative work is (or is not) female is thus less important than their position as a responder to a mainstream culture industry that is dominated by men, and consistently reproduces male perspectives. Resistant reading practices are consistently considered feminine by default.

[1.3] The continuity of practice by teenage girls as fans is not evidence of some inherent quality in young women, but evidence of the continuing marginalization of their views and interests in Anglo-American culture. Despite enormous social change regarding the economic and social opportunities for women in the course of two centuries, the markers of quality in canonical texts have not greatly altered; English-language literary and media traditions are heavily dominated by male producers, and by content and themes that privilege male perspectives. Since practices associated with femininity are culturally devalued, these bricoleur practices remain in the margins. The continuation of the same resistant reading practices across two centuries speaks to their effectiveness for expressing particular ideas, and drawing out subsidiary themes from cultural texts. These are practices performed, in part, for personal pleasure, and shared within a community to ensure that those who experience similar feelings of marginalization can also find enjoyment that is lacking from the consumption of standard publications. Though Tumblr is often used as a space of social organization and resistance by marginalized communities, I would suggest that it is the limitations of bricolage practice for resisting dominant norms that suggest why, and how, dominant hierarchies of value are often replicated in the otherwise resistant creative spaces in which transformative works are shared.

[1.4] It is possible to work as a bricoleur without recognizing oneself to be a poacher, in Michel de Certeau's terminology often used in fan studies. As Derrida notes in his response to Lévi-Strauss (1978), all thought and discourse exists within what is already available; it is impossible in human culture to create a completely original thought or image that bears no trace of the cultures and histories of its means of production, and its producer. A smooth bricolage can blend into the conventions of the dominant form, and disrupts the reader as little as possible in its reconfiguration of the material. In a telling example of the "Barack and Joe" meme that peaked in 2016, shared by Twitter user @bihighlife, Joe Biden states, "I replaced all of the books with slow burn fanfictions…I want Pence fully invested when he realizes it's gay." This instance of the meme relies upon an understanding of smooth bricolage practices; in this case, the slow interpolation of queerness into a previously accepted fictional diegesis, to ensure that a reader must emotionally connect with a character before they are presented with a viewpoint or action that challenges their preconceptions. A punk bricoleur, who deliberately rips the sign from its setting, makes the viewer aware of their own cognitive dissonance as they must contemplate the juxtaposition of meaning and text. Neither of these forms is inherently more politically progressive than the other; and fandom is fully aware of the possibilities for both modes of resistant reading. The circulation and creation of transformative works on Tumblr in the bricolage that occurs within a single collage image, and/or in the juxtaposition of posts in the scrolling timeline, has the potential to be both radical and conservative.

2. Themes and memes: Consistency in textual practice

[2.1] Before printed books became affordable to a wide market, educated persons would keep handwritten books of useful, devotional, or interesting excerpts transcribed from expensive and/or rare texts, a practice dating back hundreds of years. These collections might include sketches or maps, and also song lyrics and poetry. These books circulated among middle- and upper-class households, so that a poem, drawing, or message could be collected from absent friends or distinguished visitors. Many of the most popular authors and poets of the romantic era appear in these albums, contributing work in their own hand, copied across by another, or in print as a cutting from a commercial publication. However, it is in the visual representation and creative expression that the continuation of practices is seen most clearly across these works to the present day digital platform. I originally approached commonplace books, as a scholar of the Gothic, to explore the circulation of romantic poetry, and was struck by the visual commonality between some of the albums and Tumblr pages within fandom. There are, also, many textual modes used in commonplace books and sentiment albums that are still in use today as ways to resituate and respond to popular culture (note 1). The romantic-era albums examined for this study are drawn from the Sir Harry Page Collection held by Manchester Metropolitan University. This collection spans the romantic to the Edwardian period, and comprises diverse forms, from the dense textual commonplace book to the wholly pictorial scrapbook. Of the 285 albums in the Page Collection, identifying details of the owner/creator have only been established for 112 so far, and of this number, 66 authors are identified as women and 44 as men, based on their name or direct textual references to their gender. This is a slightly more feminine weighting than is suggested by demographic studies of social media, performed by users such as CentrumLumina (2013). Images in this article are from two albums in the Page Collection: #178 has a title leaf identifying the owner as teenager Elizabeth Reynolds and giving the date as 1817, and #2 was produced by E. and T. Wilson, between 1800 and 1830, whose relationship and genders are unknown. The differences in presentation and content are outlined below, with descriptions to highlight the aesthetic and thematic commonalities between the romantic sentiment album, and practices on the modern microblogging site Tumblr.

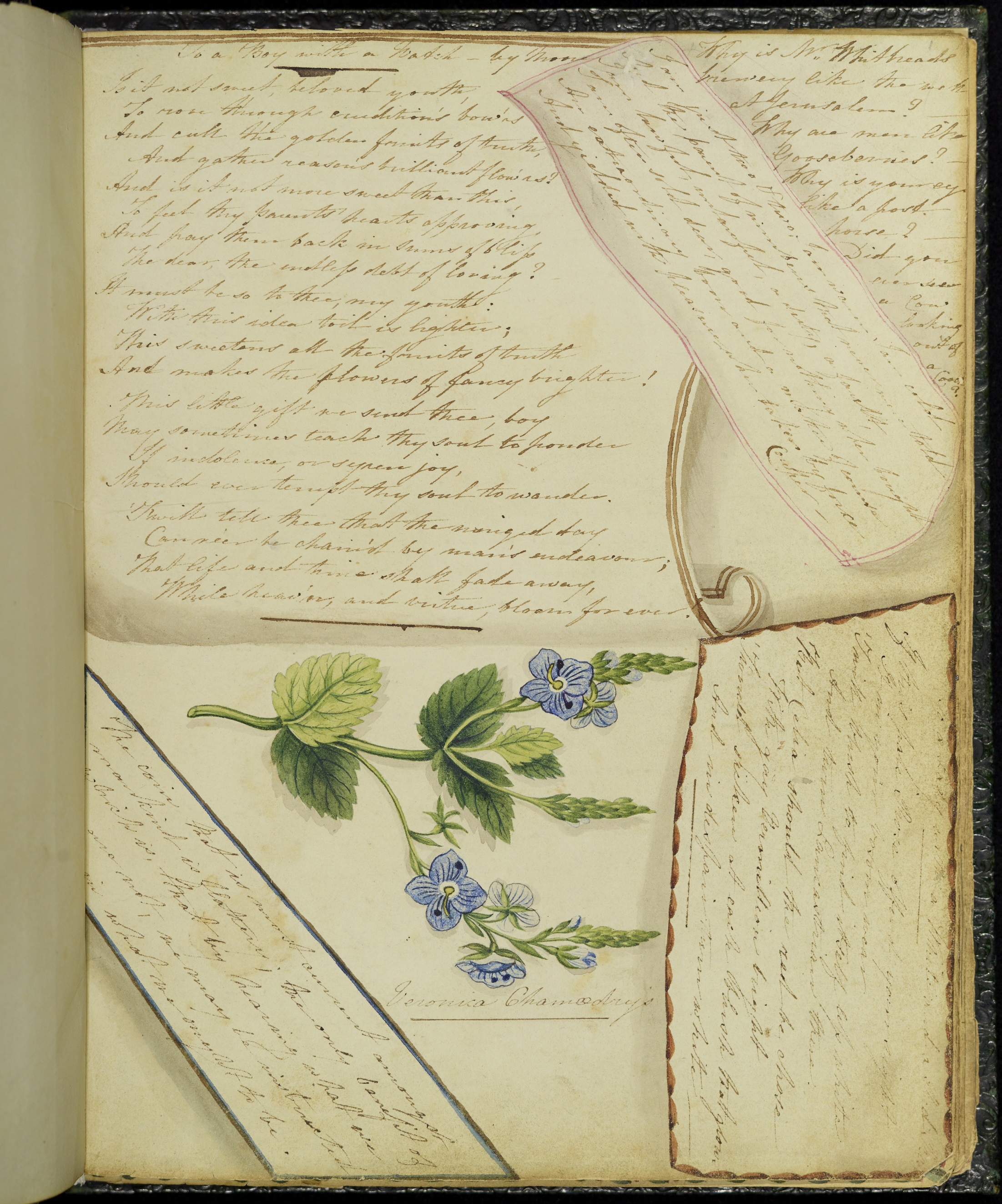

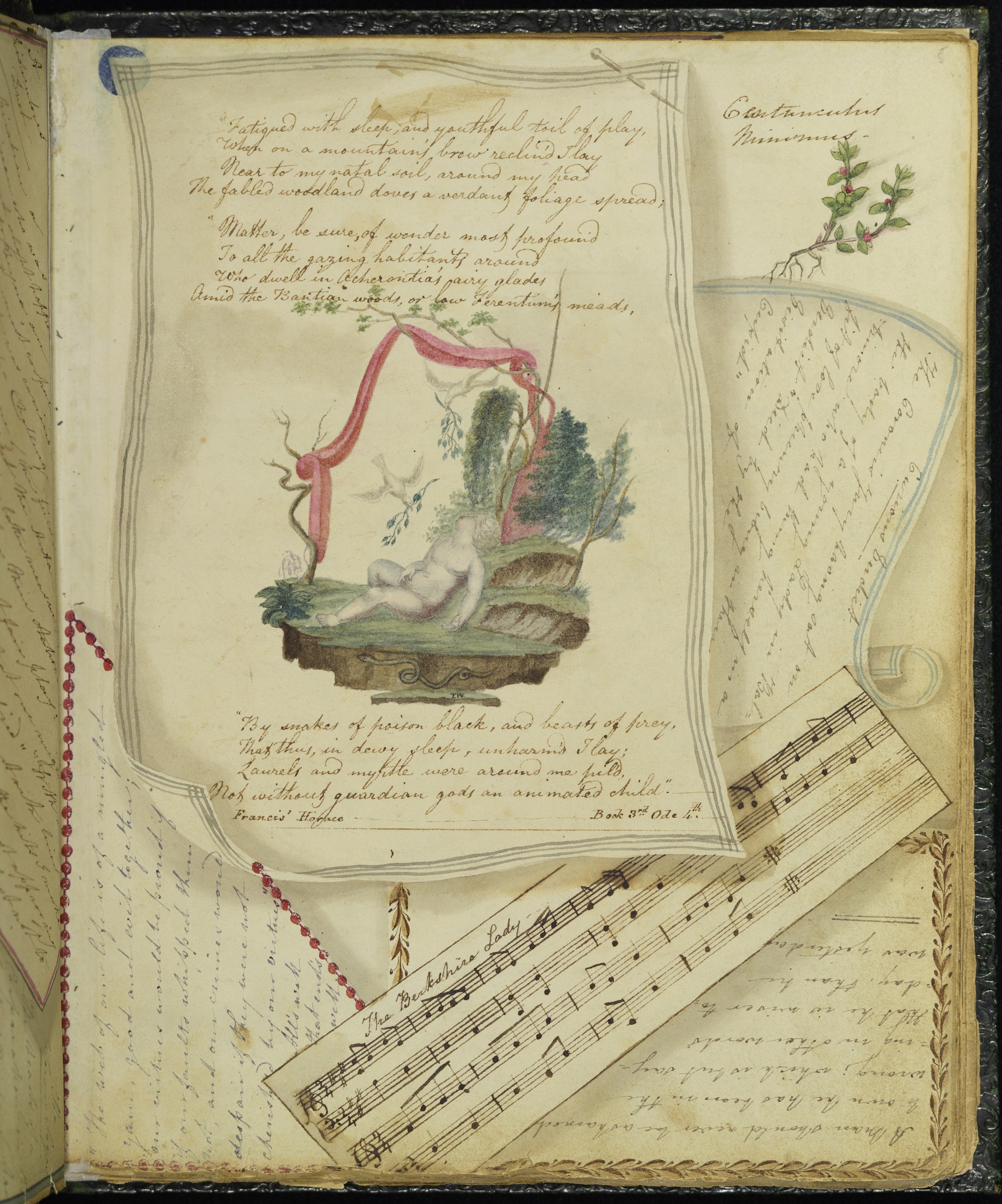

[2.2] These first images are from the Wilsons' commonplace book, in which the paper has been divided into portions to give the impression that multiple notes and scraps have been pasted into the pages. This album was unfinished, and the final pages show the process by which the pages were subdivided, the trompe l'oeil effect produced with pencil and ink, and then the content added at the final stage. The extra effort, and cost, expended to achieve a consistent look and feel also demonstrates the importance of this textual space for its creators and their desire to entice and engage others with their work. The angles of the various texts on the page of this album require the reader to repeatedly turn the book around in their hands, which would be frustratingly inefficient if this were simply a record of favorite quotations for personal use; the visual schema is clearly designed to engage an audience. This styling reflects the idea of the theme for online blogs. Themes for Tumblr can be purchased or created, as on other blogging platforms, to impose a distinct and consistent style for the display of a blog's content. In both book and blog, the use of a consistent style unifies what might otherwise seem utterly disparate content; it suggests to the viewer which content is most important by visual highlighting, and signals the creativity and style of the owner.

[2.3] The compilers of album #2 show considerable skill in painting and drawing, not only in the construction of the theme but also in the inclusion of illustrations and small maps. The paintings of flowers, as seen in figures 1 and 2, are labeled with care and seemingly drawn from life. The practice in identifying the source of the textual material varies; while Thomas Moore has his poem introduced by name and title, an extract from Shakespeare gives no citation details at all. This might suggest that knowledge of the works of Shakespeare is assumed, and the compiler is performing a familiarity with the text, or it might suggest the opposite—an ignorance of the source. Homilies, such as the one about the "coin of flattery" displayed below the poem by Moore in figure 1, were included in many popular books of quotation in this era. Books such as The Orator, Being a Collection of Pieces in Prose and Verse Selected from the Best English Writers (1776) compiled by William Perry, and Elegant Extracts: a copious selection of passages from the most eminent prose writers (1812) compiled by the publisher, did not always credit the source of their contents. It is possible that the Shakespearean extracts were derived from such collections. As with the elegantly framed quotations that circulate in online spaces for affirmation or inspiration, the source is often unknown, and the text has become a currency of its own, divorced from its original context. There is thus little evidence of detailed textual engagement with original sources and longer works in this album; how well the compilers knew the texts from which their material is culled, and how widely read they were, is impossible to ascertain. This album has been constructed to suggest that the maker is talented and discerning; the content was selected to imply a high level of cultural knowledge, which contrasts with the effect created of hastily pasted scraps of paper and pinned notes, that suggests they wear this learning lightly. This is quite a conservative display of cultural texts and tastes.

Figure 1. Page of commonplace book number 2, displaying a detailed drawing of Veronica flowers (known as Georgia Blue) and several extracts of poetry and a homily, each as though on a separate scrap of paper with decorative borders in varying colors. Sir Harry Page Collection, Manchester Metropolitan University, Special Collections.

Figure 2. Page of commonplace book number 2, displaying a brief stave of music, some poetry, and a pastoral picture in classical style. Each appears as though on its own scrap of paper, and pins have been drawn as though holding the scraps in place. Sir Harry Page Collection, Manchester Metropolitan University, Special Collections.

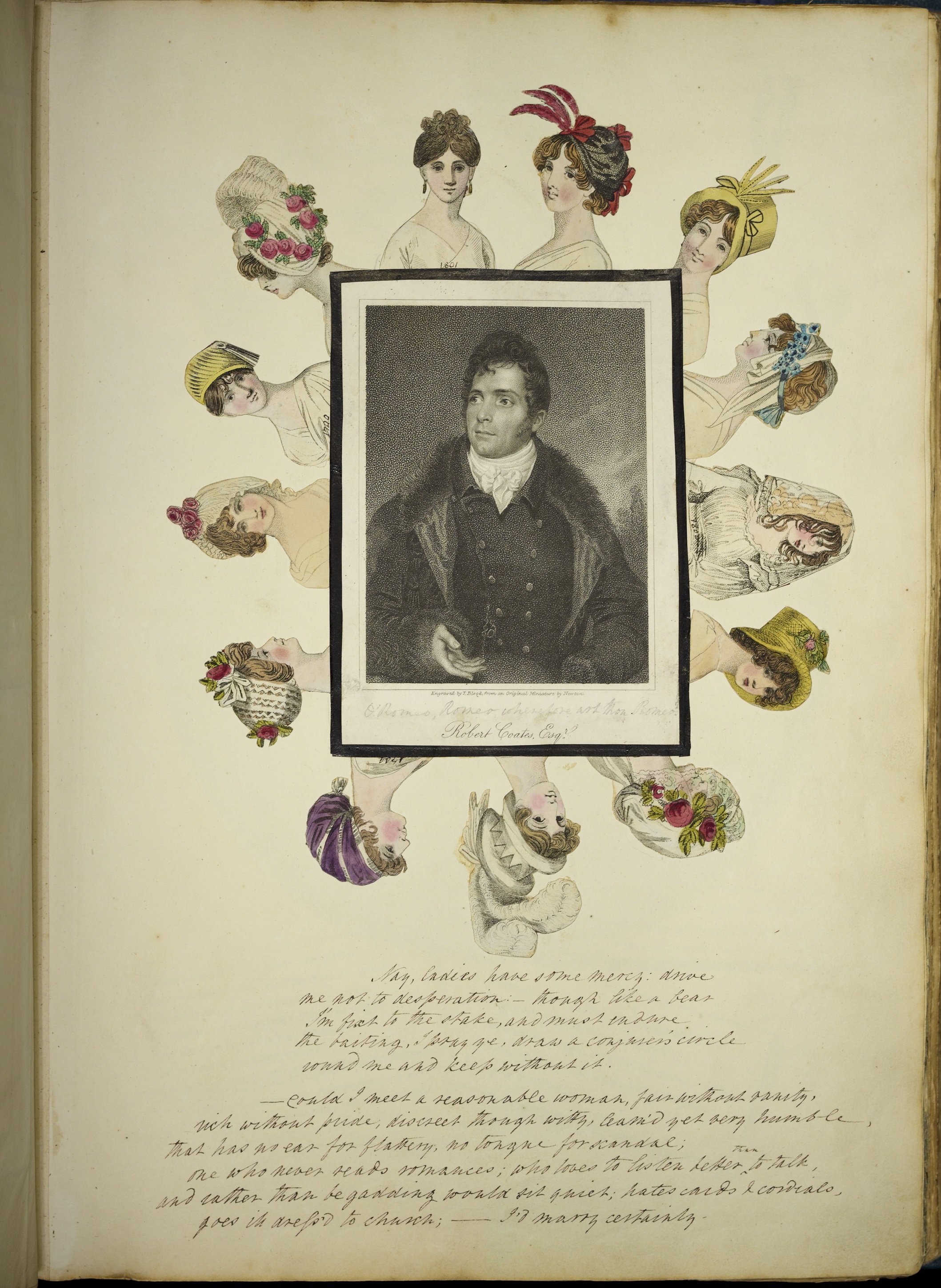

[2.4] Themes are visually enticing, but not all albums (or microblogs) are so clearly designed for a wider audience. Album #178 (figure 3) belonged to a teenage girl, Elizabeth Reynolds. It is less structured than the Wilsons' thematic presentation, and the content is often more personal, though the theme of romance and relationships between men and women predominates in both. Instead of a consistent visual style, the dominant form in #178 is collage, which brings disparate elements together with the direct intention for those elements to inform one another to make meaning with, and through, the assembled materials, in Lévi-Strauss's terms. Each page of collage stands alone, much as each post or piece of fan art might do in a Tumblr blog without a set theme. In figure 3, Reynolds has surrounded the etching of a man identified as Robert Coates, Esq., with images of women that bear no direct relation to him, in a nonnaturalistic layering. The monochrome portrait of the gentleman stands in marked contrast to the hand-painted coloring that brings out the detail of the female busts. These images are open to interpretation by the viewer—the added quotation from Romeo and Juliet (ca. 1595) and the fashion plate busts, create a unified theme of traditional heteronormative romance with a hint of tragedy; the black border to the portrait suggests mourning, which would echo the end of Shakespeare's tragedy. However, the extracts copied below the collage complicate a simple reading of admiration or memorialization; from John Tobin's The Honeymoon (1804), the plot of which echoes The Taming of the Shrew (ca. 1590) as a haughty young woman is courted and tamed, the monologues convey rather misogynistic antimarriage sentiments. This album's lack of clear boundaries, and any form of citation, bring all the elements of the page into direct contact, suggesting that the content, rather than the source, is important. The exact nature of the compiler's interest in her subject is impossible to ascertain; Reynolds may be memorializing a man she knew, or this collage might be a more general reflection on the romantic norms circulating in her social milieu. The potential is with the audience for a conventional or a radical interpretation.

Figure 3. Page of commonplace book number 178. Below a black-bordered portrait of a fashionable young man is penciled "Oh Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?" Sir Harry Page Collection, Manchester Metropolitan University, Special Collections.

[2.5] I would suggest that Reynolds's arrangement communicates to the reader a more personal engagement with the original texts than does the Wilsons' album. The Wilsons' aim for their album is clear; the reader can acquire knowledge, and/or recognize the knowledge of the compiler. Extracts and poems about romance and interpersonal relationships are not overtly given more or less weight in the design, and no personal opinion can be readily discerned, apart from a general support for cultural normativity expressed through the dominant markers of literary worth. Elizabeth's view of her audience is less clear; her collages aim more for an artistic expression, suggestive of conveying emotion or narrative rather than factoids about the external world. These two modes can also be seen in Tumblr blogs: some compilers remain emotionally detached while creating or circulating items of interest on a theme (for example, collections of on-set photographs, acting as an anonymous resource to others); other bloggers create and/or reblog highly personal art or relatable content directly referencing lived experience.

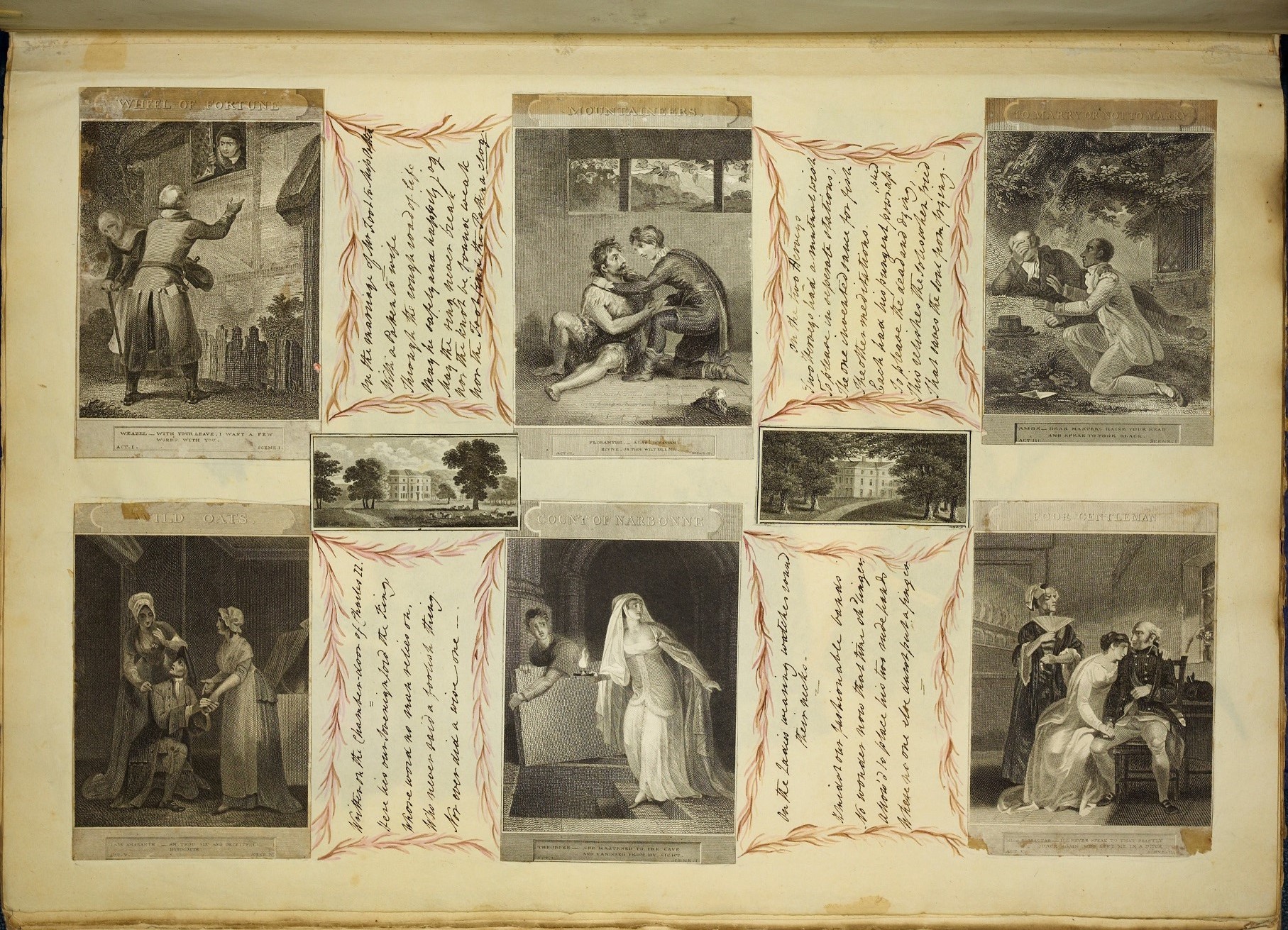

[2.6] Figure 4 shows another recontextualization of scenes from dramatic texts from album #178, this time presented pictorially. The small prints arranged in a grid pattern are each drawn from a different play, though they share a visual format suggesting they were published from one source. In this usage, these pictures can be read much like a modern GIF set, I suggest, in which short moving images drawn from a single or multiple sources are arranged in sequence to either suggest a new narrative or focus the viewers' attention on particular elements considered important by the compiler. Kayley Thomas has explored this mode in relation to repositioning villainous characters as sympathetic, as one example of the ways this pattern of extraction and recombination can adapt meaning (2013). The images used by Elizabeth Reynolds all include a citation to the play from which they are taken, as a modern GIF might have a subtitled line of dialogue or description of the action. If we read across from left to right, top to bottom, we can construct an effective narrative from the source material. In the first illustration, from Robert Cumberland's Wheel of Fortune (1795), a lawyer seeks out a recluse, who retired from the world after a bad love affair, to inform him of his inheritance. The inheritor decides to use his new fortune to exact revenge against the man who wronged him. Next is a scene from George Colman's The Mountaineers (1791), in which lovers Floranthe and Octavian are united, the woman disguised as a boy. Then we have an image from Mrs. Inchbald's To Marry or Not to Marry (1805), in which a man receives word that his daughter has eloped, and is made desperately unhappy by the news. The fourth picture in the set is from John O'Keefe's Wild Oats (1791): the character Ephraim is discovered attempting to woe an unwilling lady, which demonstrates his religious hypocrisy. The penultimate image is from The Count of Narbonne (1780) by Robert Jephson, where a young woman flees from a marriage to which she does not consent. The final illustration is drawn from George Colman's The Poor Gentleman (1802), and depicts an old father comforting his daughter, though he is facing ruination. These scenes can thus be read as a narrative in which a girl is seduced by a man for revenge against her father and, given the implications of the wider texts from which the images are drawn, though she succeeds in escaping the physical horrors of seduction, it is not certain that she saves her family's reputation. Unlike the previous collage surrounding Robert Coates, Esq., this compilation would require the reader to use the citations provided to create a composite meaning, demonstrating the compiler's familiarity with the wider text from which their reference is derived. Of course, it is possible that this reading projects the form and expectations of the GIF set onto an earlier mold and model. Nonetheless, whether Elizabeth's aim was to create a coherent narrative or not, the action of arranging these scenes has clearly been considered and thus echoes in aim, if not form, modern fan practices of recontextualization. This gallery, as with all the creations made from borrowed parts in these formats, is open to interpretation and resists fixity of meaning in the original text, the derivative images, and in its own reconfiguration.

Figure 4. Page of commonplace book 178. The six images of the dramatic set are separated by small poetic asides in red borders, which are written at a ninety-degree angle, suggesting another interplay of space, text, and meaning. Sir Harry Page Collection, Manchester Metropolitan University, Special Collections.

[2.7] The lack of rigidity in meaning that Elizabeth achieves is further demonstrated by the lack of structure in this volume. Unlike the commonplace books modeled after John Locke's instructions for scholars, explored in the third section of this article, this album invites the reader to wander between themes, creating juxtapositions of ideas and the possibility for many dissonant readings. In figure 4, we can see that short quotations from satirical verses are interpolated between the images, seemingly unrelated to the content of the stage drama. As with album #2, the reading of these different sets of texts requires the viewer to turn the book. I propose that the framing device of the drawn feathered swags suggests that these brief verses are to be read as a separate entry to the visual story that is constructed on the same page. However, given that there are multiple blank pages toward the end of the book, the decision to have these two sets of content share one page is not wholly one of necessity; yet any suggestions for thematic links or the intent of the compiler would be pure conjecture. What is certain is that these choices demonstrate a thoughtful engagement with the cultural materials.

[2.8] These albums demonstrate two differing approaches to compilation: #2 seems primarily designed to communicate a level of learning, whereas #178 seems to privilege narrative and emotional response. This is important within the gendered context of contemporary opinion regarding the commonplacing tradition and the perceived differences between a traditional commonplace book and a sentiment album. Despite its foregrounding of aesthetic design through thematic unity, album #2 conforms to many of the ideals of the commonplace book as promoted to scholarly men as a repository of knowledge but, ironically, never demonstrates an engaged readerly knowledge of the texts quoted. There is no evidence of the Wilsons having read the originary texts, such as would be suggested by a careful juxtaposition that would lead the reader to reflect on the nuances of the works' themes. Album #178, with its seemingly frivolous collages of fashion plates, some of which include feathers and mixed materials, by contrast demonstrates an active engagement with the texts from which it borrows. The use of the quotations suggests, through emotional and narrative resonance, that the compiler knows the wider context of the original material. I would term these different styles passive and active readership, in echo of the contemporary theories of reading.

3. A material difference: Gender and compilation

[3.1] Active, rather than passive reading, was discussed as an important distinction in the romantic era; Coleridge railed against modern novel readers and "their past-time, or rather kill-time, with the name of reading. Call it rather a sort of beggarly day-dreaming…the trance or suspension of all common sense and all definite purpose" (1817, 49). The associations between novel reading and femininity were well established in this period, and opposition of passivity to activity culturally aligns with ideas of masculine and feminine attributes. Corin Throsby suggests that commonplace books can be viewed as "the ultimate example of readers interacting with a text, constructing meaning in a quite literal and physical sense" (2009, 230). However, critics such as Peter Beal and Ann Moss have suggested that the practice of compiling a commonplace book transforms reading into an exercise that turns the text into a source of fragments, and the act of reading into a hunt for extracts rather than a process of engagement (Brayman Hackel 2005, 143). This echoes descriptions of the fannish bricoleur as in some way damaging an original text, or its wholeness. In these criticisms we can see the different purposes of commonplacing contrasted between an active personal response to meaning construction through ideas expressed in the text itself, and a more passive and performative consumption of the text as object, and as a signifier for cultural values such as education and erudition.

[3.2] The romantic era was a key period of change in the popular perception of the commonplace book in Anglo-American culture. In the previous century, John Locke wrote a guide to compiling and indexing a commonplace volume, the nearest modern equivalent to which might be a bullet journal, with an emphasis on the utility of the collection for reference. In the late eighteenth century, bound albums were produced on a large scale commercially, either blank for the purpose of traditional commonplacing or already filled with a selection of poetry, art and prose, often designed as a gift item. The interior of a sentiment album shows its divergence from the careful indexing and dense texts of the earlier Lockean ideal. Richly colored and full of art, pages may be pasted in from other sources with no regard to the matching of materials; there are rarely indexes, and organization might be by a theme known only to its owner. The result is vibrant but chaotic, and leads the reader by chance rather than by design. That these became known as sentiment albums reflects the connotations of emotion and affect and, by association, femininity. The gender associations between these formulations is clearly binaristic; active, intellectual pursuit is traditionally coded as masculine, whereas passivity, consumption, and performance are coded as feminine within mainstream Anglo-American cultural discourses about cultural engagement.

[3.3] That Locke, whose philosophy championed a division of the self and the body, was influential in the culture of commonplacing links the intellectual tradition of masculine humanism—which privileged the rational mind over emotional response or bodily sensation—to the act of knowledge acquisition, and particular textual practices. Lucia Dacome (2004) explores how Locke's model of the commonplace book develops the links between the construction of knowledge and conceptions of the self in the Enlightenment. By the end of the eighteenth century, the idea that identity and selfhood were functions of the mind, rather than the mechanistic flesh, was an accepted philosophical concept. Women, under this schema, are associated with emotion and sentiment, which is aligned with bodily response. Thus, commonplacing was a traditionally masculine activity, and as women engaged increasingly with this practice, their compilations were termed sentiment albums. This redesignation indicates key differences in organization and theme, even though the two modes share many of the same traditions of compilation, and the use of these terms and these books became highly gendered. Likewise, Alexandra Simpson aligns Tumblr with the construction of the self, in that it "archives the acts of identity formation. Queer fandom…can help to assemble a user's self and provide an anchor, drawing other like users together" (2015, ii). Just as the forms associated with masculinity were considered to have more cultural value in the romantic era, so the continued denigration of femininity and queerness lead to contemporary pejorative judgements about "Tumblrinas" and "otherkin" being used on platforms like Reddit and Twitter regarding Tumblr. Thus, the digital and the paper spaces of compilation are textual forms intimately associated with identity.

[3.4] It is notable that, as commercial sentiment albums developed, precompiled commonplace books full of notable extracts and wise excerpts were also often aimed at women or a family audience. However, guides to creating one's own commonplace book, full of active scholarly learning, were still aimed at men. It was also popular for male family members to compile collections for their female relatives, to guide them in their tastes. In commonplace book #19 in the Page Collection, created by a man in the 1790s for an unnamed woman in his family, the compiler wrote an introduction, stating:

[3.5] It has been thought that a woman's reading should be confined to such books as are directed to the imagination and fancy, asserting that they have not capacity for any other subjects, and admitting they had capacity, these declaimers of the fair sex, will have it, that any other sort of reading, only makes troublesome wives and inattentive mothers.

[3.6] Though respectful of women's intellectual capacity, the author goes on to place woman's learning with reference to the benefits to her family, likening a woman of learning to a safe harbor for men in society. Women are clearly considered to engage with culture in the wrong way, and must be guided because they are sentimental, emotional, affective, and passive. Collections of supposedly appropriate content were published to guide the compilers of sentiment albums, one of the earliest being Original Album Verses and Acrostics (ca. 1800), published in Toronto, Canada. These efforts demonstrate that attempts to incorporate textual practices associated with women into the commercial publishing or media industries have long gone hand-in-hand with attempts to control, or to denigrate, the content women consume.

[3.7] Attempts to contain and control the intellectual and creative pursuits of women speaks to Judith Fetterley's argument that literature, and cultural production more widely, is inherently masculine, even as commercial publishing exploits female fan labor for content, and denigrates the fan for overtly gendered reasons. The feminine genres, such as romance and the gothic, associated with strong emotions, sentiment, and femininity, are much mocked in form, content, and readership. Female reading practices are, traditionally, not viewed in positive terms. In 1819, the genre fiction fan Amelia Hopeful wrote to the editors of The Fireside Magazine, saying that her favorite books are called trash, but that she still wants to be a romance writer herself (April 1, 1819, 121). All Amelia received in response was mockery that targeted her supposed lack of feminine skills and virtues, through a satirical depiction of her neglect of her domestic duties:

[3.8] Let her not trouble herself about the making of a pudding or a pie, or any such servile occupation…Food, too, the consideration for which belongs only to such whose appetites are depraved by sensuality, and which we never read of as occupying the thoughts of a heroine of romance, is far too gross a thing for the refined imagination of our correspondent. (122–23)

[3.9] Amelia outed herself as a fan in good faith, hoping that a literary magazine would support literary endeavor, regardless of gender. Tumblr fans, with their content made searchable through aggregating search engines like Google, do not have to reach out to published media to find themselves featured within its content; there are articles on sites like BuzzFeed and Comedy Central with titles like "17 Riddikulus Harry Potter Fanfiction Quotes" culled from the publicly accessible platforms.

[3.10] There are two particular forms of criticism to note, when discussing the condemnation that both fans and commonplacers face: criticism of the quality of their cultural choices, and criticism of their mode of engagement with that culture—though these approaches are often combined, and both are heavily gendered. The collection of sports data and trivia is thought of as a masculine pastime, and the creation of fan fiction and the emotional investments of shipping considered feminine; yet the male sports fan may weep in public openly at his team's failure, and the female media fan compile endless data on a wiki for a television show. As Kristina Busse notes, female fans' emotional responses are consistently delegitimized, not only as appropriate responses to media, but as fannish responses in and of themselves "clearly marked as a not good-enough fan,…because she is a fan for the wrong reasons and in the wrong way" (2013, 87–88). The judgments of typical fan behaviors are formed within a complex network of gendered expectations. The behaviors, the bodies, and the fan objects each bring a gendered significance into the equation. The female sports fan who collects statistical data about baseball may find herself more readily welcomed than the female hockey fan who ships teammates, as Busse notes that a female fan of the Lord of the Rings films is rejected for investment in the actors above the world-building of the narratives (2013, 87). The linking of bodily identities by gender and sexuality with specific textual practices and spaces is thus a consistent theme in both critical and celebratory explorations of both the sentiment album/commonplace book and microblogging platforms.

[3.11] The differences between the commonplace book and sentiment album are gendered in similar ways to modern fan practices and spaces, in which associations of femininity and queerness are considered damaging because they suggest illegitimacy. Peter Beal describes the changes in the commonplace book; from having been "the primary intellectual tool for organising knowledge and thought among the intelligentsia…of the seventeenth century," to being thought of as "degenerated to a plaything" by the nineteenth century (1993, 134). Note that ideas of immaturity and play are contrasted against intellectual thought, aligning women with childishness and men with rational maturity, just as fan scholars like Henry Jenkins have long noted in discussions of fandom and fan practices. Although reliable usage data based on gender or other demographics is not available for either digital platforms or commonplace books, what is most important here is the dominant public perception. Femininity and queer sexuality are culturally associated with Tumblr, and Tumblr is thus likewise associated with youthfulness, immaturity, and emotional irrationality. Nagle seems to suggest a direct alignment of the development of queer identity with Tumblr usage by young people, and then uses this alignment to denigrate political movements she disagrees with (2017, 69–74). Thus, women's use of a platform can lead to it being considered a denigrated form: under the binaristic understanding of gender in the dominant culture, that which does not share the dominant perspective, which is ironically figured as a neutral perspective, is feminized and/or queered by bodily association.

4. The bricoleur and the poacher

[4.1] As I have outlined, the exploration of the material spaces in which the romantic-era compilers are working demonstrates the distinct similarities in practices of recombining visual and textual elements in aesthetics and form with the digital platform of Tumblr. To explore the ways in which these practices create meaning, I situate them as examples of what Claude Lévi-Strauss terms bricolage. The bricoleur works with materials that are already available, but with an eye to creating a meaning that is new or different from what is currently available; he "interrogates all the heterogeneous objects of which his treasury is composed to discover what each of them could 'signify' and so contribute to the definition of a set which has yet to materialize" ([1966] 2004, 18). The textual response practices familiar to both contemporary Western media fan spaces, and in the construction of the sentiment album, can thus be said to demonstrate an impetus to subvert meaning. However, this perspective suggests that there is perhaps a fixity to originary meaning, and an ownership inherent in authorship. This formulation echoes also through explorations of fan practice such as Henry Jenkins's theorizations based on Michel de Certeau's notion of textual poaching. Ideas of appropriation and poaching bring to the fore ideas of a power negotiation, suggesting that at the heart of these textual remixings is a contested ownership of the text. In foregrounding the concept of bricolage, I hope to approach from a new direction.

[4.2] The terms bricolage and poaching, although often combined in textual readings of fan practices, are not synonymous. The terminology of textual poaching is overtly about ownership, and the politics of access and use. Bricolage, on the other hand, simply means working with existing materials, and does not directly address the source of those materials. While it is productive to bring these concepts into dialogue together, I also believe it is important to separate them—to be able to explore bricolage practices as situated within, and products of, the power structures that control content, without these practices necessarily actively engaging with a dialogue of ownership. Jenkins suggests that fan bricolage is a process "through which readers fragment texts and reassemble the broken shards…salvaging bits and pieces" (1992, 27). The language used here reflects these ideas of ownership and textual wholeness, with the idea that the compiler has broken an original text. Yet the clipped prints used to construct a tale told in pictures in sentiment album #178 are not broken shards, but rather carefully adapted portions of a text that were reframed by an artist, possibly to illustrate the original work itself. They were very carefully excised from their original setting by Reynolds's scissors. The idea that these are jagged shards that do not fit smoothly together in reassembly suggests a more chaotic process, and one that in some way damages the source material. Jenkins's idea of salvage, I think, is more apt, providing an image of the bricoleur as taking cultural flotsam and jetsam: these small images were set adrift from their originary source as soon as they were made; they were created as fragments, as their attached citations attest. This is the same for GIFs; carefully constructed to convey a brief moment, they circulate on digital platforms divorced from their original context, but whole in themselves as communicative memes. The ownership of these images is unimportant; their content is often their sole value in their reuse.

[4.3] Negative portrayals of both microblogging and commonplacing often suggest that particular textual practices and readings are wrong or illegitimate, just as the imagery of breakage suggests they are damaging, and this certainly makes these transformative works resistant to the dominant narrative. Fetterley suggests that the American canon of literature, legitimated by scholarship and traditional publishing practices, excludes the identities, the very selfhood, of women. As the literature that is lauded foregrounds a male viewpoint, Fetterley states that "to be universal, to be American—is to be not female" (1978, xiii). To not accept the invitation to identify with the central protagonists directly, to read without becoming part of a universalized image of a human that elides gender, race, nationality, and other bodily markers and experiences of identity, Fetterley terms "resistant reading." In Fetterley's analysis, resistant reading, and the feminist criticism that it produces, represents "the discovery/recovery of a voice, a unique and uniquely powerful voice capable of cancelling out those other voices…which spoke about us and to us and at us but never for us" (1978, xxiii–xxiv). I posit the bricoleur as a resistant reader, one who seeks to reassert the individuality of his or her identity as a reader, to vocalize that which has been left out of the texts they are offered. However, this should not lead us to assume that the content creators are engaging directly with ideas of ownership, or are overtly attempting a challenge to traditional notions of authorship, because they suggest that signifiers are multivalent. The resistant reader, as theorized by Fetterley, is, by definition, an engaged and active reader but not necessarily an activist reader. I want to suggest that reading these modern and past compilers' actions as those of a bricoleur, rather than a poacher, enables us to understand the lack of direct political engagement in many fan works more effectively as an act of resistance defined as separate from an activist activity.

5. The limits of the bricoleur as resistant reader

[5.1] The compilation techniques of the sentiment album and Tumblr blogger suggest important similarities in the experiences of those creating transformative works in two differing eras. I have suggested that the construction of multimedia reinterpretations of popular texts is popularly constructed as a distinctly gendered practice associated with young women because it is a resistant mode of reading. This is because readings from perspectives foregrounding nonmasculine or nonheterosexual experiences of sexuality and gender are constructed as resistant, within a literary tradition that privileges rationalist, disembodied (yet predominantly masculine) perspective. This circularity of signification ensures that these practices are marginal. The practices of bricolage have often been advanced as politically resistant; Dick Hebdidge uses this concept to analyze symbols of political resistance in youth subcultures of the twentieth century. His analysis recognizes the limited access to materials experienced by poor working-class youths and that, in overtly political subcultures, the signifiers are chosen because they have already attached signification that is deliberately subverted through the "explosive junction" of seemingly incompatible elements (1979, 106). The bricolage effected by a punk to demonstrate alterity to middle-class notions of commoditized success can thus seem ideologically oppositional to the bricolage assembled by a fan of romantic narratives who wishes to extend the genre. The former seeks to rip apart the signs and signifiers and demonstrate their lack of fixity, seeking the possibility for a new system of meaning; whereas the latter seeks to join in with already established systems of meaning. (This is not to suggest that demanding space within the current system cannot be a politically resistant action, of course; the campaign for same-sex marriage, for example, fundamentally challenged political exclusion.) However, as previous critics who have worked with commonplace books have suggested, "there is a danger of attributing too much subversive significance to commonplacing—it is very unlikely that the women who owned these books saw themselves as part of a 'counterculture' of readers" (Throsby 2009, 234). The creation of transformative works is a resistant reading practice by default, but this does not necessarily always make its practitioners political by design.

[5.2] Transformative works and spaces can be seen to perpetuate the dominant discourse because the participants work with preexisting materials without interrogating the history, use, and meanings attached to those materials. A key current debate within cultures of transformative works on Tumblr, and in academic and other reflective discourse around Tumblr, explores the predominance of white characters and ships within fandom, and the whitewashing of people of color in official adaptations and other derivative works. There are whole microblogs devoted to the discussion, with names such as starwarsfandomh8speopleofcolor and fandomhatespeopleofcolor. As blogger Ryn Silverstein (2013) writes, "As a digitized space constructed primarily around hierarchies of image, Tumblr is particularly suited to visual expressions of identity," yet "so much popular fanart feature whitewashed characters of color, even when the characters are explicitly racialized in the source material." Thus, it is my contention that fan practices have remained remarkably consistent from the sentiment album to the microblog because, even though reformulation enables creators to advance a voice that can speak for us, rather than about us and to us, they are unable to do as Fetterley suggests, and cancel out the dominant voice. A resistant reading is always a response to an existing voice, just as bricolage works with material that always has a "history, use and meaning," as Leoni Schmidt and Jeroen de Kloet note; the bricoleur "always works with hindsight" (2017, 100). How radical can resistant readings become, and what disruptive potential do they hold, when they continue to work with, rather than replace, the materials created within the patriarchal tradition?

[5.3] The radical possibilities for bricolage require us to focus less on the ideas of ownership when considering meaning making, and more on our own individual responsibility as users of symbols and images. In discussions about which fan practices come under academic scrutiny, much is made of participatory cultures, and the authenticity or the ownership of the space as well as the content. All fandom is figured as a response to an original, a fan object. However, on Tumblr, as in the pages of the commonplace book, the creator of the original content is simply another participant. The official Tumblr microblog for a star actor or television show production team engages on the same terms as any other actant, as they have limited control as to where their content ends up in the stream, what juxtapositions are made between their post and the next in any user's feed, and what tags and responses their content collects as it circulates. This echoes the commonplace book experience; the original author might have transcribed the poem into a commonplace book for a friend or a fan, but what imagery the book's owner chose to surround it with, and what content additions will be made by other contributors, is not within their control. If the work is surrounded by other literary work, the commonplace book functions rather like an art gallery, with the compiler acting as curator; value judgments based on cultural and intellectual worth might dominate. However, if the poem becomes one element within a young woman's personal romantic reflections, its intellectual properties may be secondary to the emotional, affective response it generates. A hierarchical comparison of the value of these responses is moot; what is key is the active creation of meaning. Through active engagement with cultural materials, there is no passive way to be a bricoleur, and thus we are all complicit in our meaning making.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] The capability to create radical art from conservative sources lies within all bricoleurs, but it takes conscious choice. The smooth bricolage of the GIF set can interpolate queerness or characters of color into a previously white hetcis space, as though it had always been there, effectively demonstrating belonging. This may be a radical act of reclamation, or a conservative mode that seeks to establish homonormativity alongside heteronormativity. The edits demonstrating the minimal screen time for featured actors of color, as compiled on the Tumblr blog "Every Single Word," may serve as a humorous response to marginalization, or a vigorous clapback, or both. The context is as important as the content, yet the compiler is situated in this environment of collage—in control of their materials as they create their own entry, yet unable to control the context in which it appears as it scrolls along another's timeline. Thus, we see the limits of using the flotsam of the mainstream; the original is always present, always brought into dialogue with the reedit. The lack of control over the text, the space in which the text circulates, and the juxtaposition with other texts means that there is always the potential for both conservativism and radical rereading. Thus the continuation of traditional hierarchies of whiteness and straightness in fan spaces is not simply a function of the media from which fans draw their inspiration. It is indicative of a failure to perform active reading; to demonstrate an engaged knowledge of the message of the originary text, in content or context, is as important in using this material as the use to which it is eventually put. Passive engagement always risks replicating the dominant value systems. Thus, bricolage can only be a powerful tool when it wrests meaning from ownership, and says that the former does not depend upon the latter. However, its proponents must remember that collage form—dependent upon recontextualization to make meaning—cannot afford ignorance of context in the originary materials either.

7. Acknowledgments

[7.1] Many thanks to the curators of Special Collections at Manchester Metropolitan University for access to the Page Collection, particularly Jeremy Parrett for his help in supplying images for publication.