1. Introduction

[1.1] In late 2013, Marvel Comics launched the Tumblr site "The All-New Ms. Marvel Backstage Pass" (https://allnewmsmarvel.tumblr.com/) (henceforth referred to as "Backstage Pass") in anticipation of the company's impending Ms. Marvel comic book series. Ms. Marvel stars Kamala Khan, a 16-year-old Muslim Pakistani American who takes up the Ms. Marvel mantle. She is also an ardent fan of the Avengers and other superheroes who populate her world, as the first issue of her comic establishes Kamala as a creator of Avengers fan fiction. The character was cocreated by two female Muslims: writer G. Willow Wilson and editor Sana Amanat, the latter of whom is also Pakistani American. Whereas the series garnered critical and commercial success, Backstage Pass evidences its own success by enabling a space in which racial, ethnic, and gender dimensions of the character of Ms. Marvel, its creators, and its fans are uniquely articulated, affirmed, and ennobled.

[1.2] These unique capabilities stem from Tumblr's reputation and affordances as the "fandom platform du jour" (Deller 2014) and a "particularly friendly site for women, queer people, people of color, and progressives" (Pande and Moitra 2017). While many fans use a variety of platforms, such as Facebook or Twitter, as part of their social media fandom, Tumblr distinguishes itself in the transmedia ecosystem for the ways in which it enables broad fandom coalitions to form, connect, and seamlessly integrate. Pande and Moitra (2017) describe Tumblr as highly interconnected and fluid along lines of gender, sexuality, and race, with many Tumblr sites connecting fan practices to social justice politics. Compared to other platforms, Tumblr is also more adept at inaugurating unpracticed fans into communities, learning community norms, and undertaking intertextual practices, since Tumblr facilitates an "intertextual discourse" (Thomas 2013) based on its predilection towards highly visual pictographic textuality that ultimately enables a sense of coherency and engagement among many users unfamiliar with intertextual functions. Other have singled out Tumblr as uniquely capable of helping users connect personalized narratives with broader cultural narratives, whether it's connecting personalized feminist practices to wider cultural conceptions of feminism (Brandt and Kizer 2015) or connecting personalized preferences for reconceptualizing the race of individual characters to notions of whiteness among media franchises (Gilliland 2016).

[1.3] By using Tumblr to engage with Ms. Marvel fans, Marvel Comics realized an opportunity to connect creator Sana Amanat with fans who, like herself, were eager for opportunities to assert their passions for both fandom and cultural belonging. Rather than merely promoting Ms.Marvel to fans, Amanat engaged with fans through Backstage Pass, fostering a sense of community by emboldening fans to align fandom and identity expression through social media campaigns and practices. Emboldening and rendering visible active nonwhite and/or female fans feeds into an ongoing effort by Marvel Comics to diversify its staff, creators, characters, and fans. This effort has been driven by an institutional desire for both cultural esteem and economic growth, especially as younger demographics are increasingly comprised of nonwhite and overlapping identity vectors. By opting to develop this Tumblr site, Marvel Comics signaled a desire to engender and legitimate diverse fan coalitions on the Tumblr site, as well as align these fans with the cultural bearings of Ms. Marvel and her creators.

[1.4] Backstage Pass provides a means for fans to articulate identity formations emblematic of the emergent Ms. Marvel fan culture and consistent with Marvel Comics' desire to foster a readership of greater cultural diversity. Through discursive and textual analyses of fan interactions on this Tumblr site and interviews with Wilson, Amanat, and others in the Marvel Comics institutional hierarchy, I interrogate complications among fans, industry, and identity expression transpiring through Backstage Pass, as a means to more assuredly understand the ways fan practices alternately converge and diverge with the motivations of industry. Even though Tumblr affords unique opportunities for fandoms and identity expression, understanding these complications also tracks to other social media platforms increasingly situated amidst the interplay of industry, fandom, and identity expression. In the next two sections, I account for technological and social affordances of Tumblr that give rise to unique opportunities for identity and fandom expression and, from there, I delve into interactions on Backstage Pass.

2. Tumblr and social affordances

[2.1] As a social media platform, the technological affordances of Tumblr share some similarities with other sites within the social media ecosystem. Tumblr users are networked with other users who follow the content that these users post, just as Twitter users are interlinked with their followers and Facebook users are interconnected to friends. Interaction among users proceeds along broadly similar lines of functionality and nomenclature. Content posted by Tumblr users can be liked by clicking on a heart-shaped icon, similar to the clicking of a heart-shaped icon as an affirmation of a tweet or other content proliferated through Twitter and also not dissimilar to the Facebook like function through which users may select from a series of emoticons that best express their reaction to the posted content. On Tumblr, content is accessible as a blog post and recirculates by reblogging these posts (similar to Twitter's retweet function or Facebook's share function).

[2.2] Tumblr's uniqueness as a social media site, however, owes less to its technological affordances and more to the way these technological affordances chart a pathway for distinct social affordances. Scholarly research on Tumblr has thus far considered the site's sociality with regard to affect, self-identification, and cultural exchange within LGBTQIA communities (Cho 2015; Oakley 2016; Fink and Miller 2014); the formation of self-injury narratives (Seko and Lewis 2016); conflict around the use of selfies in a Not Safe For Work (NSFW) community (Tiidenberg 2016); postfeminist conceptions of individuality and conformity (Kanai 2017); and counterpublic communication and interaction (Renninger 2015). A particularly vibrant thread of research focuses on Tumblr as a facilitator of fandom performativity, expression, and practice (Deller 2014; Thomas 2013; Booth 2015; Gilliland 2016; Gonzalez 2016; Pande and Moitra 2017).

[2.3] Much of this research considers Tumblr a site for renewed forms of sociality, visibility, and practice that resist normative constructs. Fink and Miller describe Tumblr as a "system of simultaneous consumption and production" (2014, 614), enabling users to supplant distinctions between producers and consumers. Tumblr therefore occupies a "liminal space between produced and consumed" (Booth 2015, 74) since Tumblr content is largely comprised of pictorial-based images and mashups extracted from other online and offline domains. Users then reappropriate, repurpose, and recirculate these images to suit their needs and desires. Through this circulation and interaction, users cohere around shared patterns of distinction and solidify group formation.

[2.4] Circulating images and other texts throughout Tumblr therefore supersedes circulation as a mere act of distribution or dispersion. Instead, circulating and dispersing texts on Tumblr fosters the creation of "intimate publics," as Tumblr engenders a "sense of commonality and likeness" (Kanai 2017, 5) through not only the circulation of texts, but through reblogging and liking texts. In this sense, reblogging and liking are not only technological modes of dispersion and interaction; they are social modalities that create a pathway for users to "gain credibility according to particularly intense systems of distinction" (Fink and Miller 2014, 615), and therefore solidify cultural bearings around issues of taste, identity, and collectivized inclinations.

3. Identity and fandoms on Tumblr

[3.1] Tumblr's chief attribute, then, stems from the way its technological affordances open up distinct social affordances. In other words, what it affords from a technological sense is important because of who is afforded renewed conceptions of expression, interaction, and visibility. Renninger notes as much when considering the value of Tumblr for counterpublics "defined by a specific non-mainstream use they have for the site" (2015, 8). This nonmainstream may be fannish preferences that run counter to a predominant taste or practice with respect to fandom communities. In many instances, the nonmainstream inclinations of Tumblr also accommodate users whose self-actualization of identity components do not correspond to normative mainstream constructs.

[3.2] In a study of LGBTQIA Tumblr users, Oakley notes that many within LGBTQIA communities acknowledge Tumblr as a "safe space where it is appropriate to display labels outside of the [gender] binary" (Oakley 2016, 9), notably in comparison to a social media site like Facebook that more prominently makes personalized information visible to onlookers. Fink and Miller also affirm Tumblr's distinction as a digital space uniquely suited to interlink users oppositional to gender distinctions (2014, 611) as well as their ability to express their own conceptions of queerness, sexuality, and sexual practice. In addition to countervailing dominant cultural norms around gender and the gender binary, these authors also note Tumblr's role in facilitating a "callout culture" in which "people of color can draw awareness to and effectively critique daily practices of racism and cultural appropriation that often go unchecked" (Fink and Miller 2014, 616).

[3.3] While Tumblr enables many to countervail dominant cultural norms, the platform is nonetheless susceptible to the permutation of oppressive modalities undertaken by otherwise marginalized peoples who amass power within the Tumblr ecosystem. Angela Nagle cites Tumblr's role in callout culture as one also prone to vicious and aggressive reprimands from identitarian vanguards whose callouts are a mix of "performative vulnerability, self-righteous wokeness, and political bullying" (2017, 76). Her notion of an "online economy of virtue" accounts for a tendency among some Tumblr users to self-promote their own marginalization, castigate would-be perpetrators of this marginalization, and thereby accumulate virtue through a concomitant exhibition of victimhood and reprisal built upon a politics of vain moral righteousness (2017, 77). Others have taken stock of Tumblr's political economy, tying its financial precarity to the vast circulation of pornography, hate speech, and the approximation of this content to intellectual property (Feldman 2017), repelling advertisers (as well as many potential users) wary of Tumblr's unwillingness to more strenuously police content. When stressing the possibilities for social and political progress in relation to identity expression and the affordances of Tumblr, the urge to conceive of a space rife with utopian purity must be weighed against asocial consequences proffered by its openness and anonymity.

[3.4] Despite these consequences, Tumblr is a particularly verdant space for the flowering of online fandoms. Just as Tumblr can enlarge possibilities for users to denormalize hegemonic constructs related to gender, sexuality, and race (as well as their intersection), the platform concomitantly provides an assured pathway for accentuated fandom visibility and practice, notably since fandom is often composed of participants stigmatized for both fannish inclinations and identification with traditionally marginalized communities of people. As John Fiske notes, the very notion of fandom is highly associated with "cultural tastes of subordinated formations of the people, particularly with those disempowered by any combination of gender, age, class and race" (1992, 30). For Fiske, fandom is suffused with a tension between intensifying attributes of normative mainstream cultures and refashioning the values and characteristics of the culture it opposes (1992, 34). In this way, fandom approximates a cultural distance that is—much like Tumblr—a liminal space of its own, one that exists between sanctioned and separatist arenas.

[3.5] Fandoms, on Tumblr and elsewhere, often circulate image-based pastiches expropriated and refashioned from mass-produced works, whether it's amateur fan art that reworks depictions of the Marvel Comics character Loki (Thomas 2013) or blogging communities that appropriate imagery and gamic rules from The Sims franchise (Deller 2014). The tension between production and consumption, normative and nonnormative, mainstream and subculture, is alive in many of these pastiche texts. Fan-made pastiches and similar refashioned texts often constitute a means of "reflecting on the multitude of available fannish work about other texts" (Booth 2015, 59) and therefore help us understand productive fandom practices as a form of pastiche in their own right. In other words, fandom produces and consumes pastiche as both artifact and practice. This dynamic further helps to illuminate the intersection of two paradigms occurring through Backstage Pass: intertextual and paratextual encounters.

4. Backstage Pass: Intertextuality and paratextuality

[4.1] The proclivity toward remixes, mashups, and other forms of pastiches and reappropriations is indicative of Tumblr as a space wherein "intertextuality develops wider coherency through its pervasive dispersion" (Thomas 2013), a coherency that gestures toward opportunities and mechanisms for disparate sectors of fandom coalitions to converge around characters, iconography, and other recognizable attributes of media texts.

[4.2] Backstage Pass is, by virtue of its orientation around the central character of a mass-produced Marvel Comics publication, an intertextual encounter with forms and imagery associated with the primary Ms. Marvel text. It's important to keep in mind, however, that the creation of this Tumblr site is not the result of amateur fans advancing their enthusiasm through off-market production. Instead, the site was initiated by Marvel Comics as a promotional vehicle for the Ms. Marvel comic, a vehicle that the company likely imagined as an opportunity to both promote Ms. Marvel to fans and leverage their productive activities as promotional vehicles, a trend increasingly common on Tumblr and other social media sites. Citing the emergence of online virality and a tendency for fan works to be reconceptualized as viral marketing, Busse notes the danger of "co-optation and colonization of fan creations, interactions, and spaces" (2015, 112), while stressing the greater danger of "actual exploitation of fan labor" (2015, 112) stemming from industrial motivations to view fannish works as viral marketing tools inflected with authentic fannish devotion. On this front, De Kosnik accounts for fan work (or labor) in addition to fan works as the realization of fan labor exploitation, since these works are infected with the performative value of fan work (2012, 100). When Ms. Marvel fans display and express their identity components in accordance with Sana Amanat and Marvel-led initiatives, they undertake work that "should be valued as a new form of publicity and advertising" (De Kosnik 2012, 99).

[4.3] For Marvel Comics and other companies, fan works are opportunities for authentic off-market promotional tools and a form mimicked by professional marketers seeking to associate their products and brands with user-generated content. In 2016, for example, the magazine Ad Age designated MTV as the brand most adept at using Tumblr to market to millennials. This designation was based on MTV's use of a short video minimalistic in its form and length, thereby connoting user-generated creativity (Ha 2016). On Backstage Pass, fan-generated works are valued, then, not only for fostering a sense of community and rendering visible particular demographics, but also for their function as de facto promotional tools imbued with authentic fannish passion.

[4.4] Even if the site is associated with Sana Amanat and the cultural attributes she shares with Ms. Marvel fans, the site's genesis stems from Marvel Comics' economic and institutional motivations. Central to this tension is the paratextual nature of Backstage Pass and the role of paratextuality as a point of inflection and deflection among industrial practices, fandom interaction, and textual components.

[4.5] Paratexts are materials that exist in proximity to a primary text (traditionally conceived as mass-produced media objects such as films, comic books, etc.) and influence the understanding and reception of the text. Jonathan Gray describes paratexts as elements that occupy a space between audience, industry, and text, elements that are actively "conditioning passages and trajectories that criss-cross the mediascape" (2010, 23), positioned as they are between audience, industry, and text.

[4.6] While paratexts can be objects that occupy a spatial domain (such as a website), "paratextuality" is the quality ascribed to the orienting capacities of paratextual elements, be they tangible objects (i.e., an advertisement) or textual associations that condition and inflect upon ascribed meanings, associations, and practices. Part of this inflection is the tendency for paratexts to function as intertexts that alternately "deflect readers from certain texts or to inflect their reading when it occurs" (Gray 2010, 36), indicating that passages and trajectories can be charted by either (or both) fandom pastiche or industrial audience management techniques. In other words, Backstage Pass is a paratext in relation to the Ms. Marvel comic, a paratext that orients fan cohesion around the character of Ms. Marvel and reorients these fans to preferred encounters with the Ms. Marvel primary text.

[4.7] These textual/intertextual/paratextual components intersect across Backstage Pass, just as the site intersects across lines of audience/industry, consumption/production, normativity/nonnormativity, and mainstream/subcultural. Given the viability of paratexts as a business practice (Gray 2010, 39), the paratextual qualities of this Tumblr site provide a sanctioned venue for Marvel Comics to embolden the intersectional identity components of the budding Ms. Marvel fandom and therefore expand the demographics, size, and visibility of its audiences.

5. Ms. Marvel, identity, and fandom

[5.1] Issues of identity and difference informed Ms. Marvel from the beginning. Marvel Comics announced the title's publication in November 2013, and shortly thereafter Marvel.com interviewed cocreators Amanat and G. Willow Wilson. When asked "who is the new Ms. Marvel? And what makes her different?" Wilson responds by describing Kamala Khan's "dual identity" as one that "struggles to reconcile being an American teenager with the conservative customs of her Pakistani Muslim family" (quoted in Wheeler 2013).

[5.2] When Marvel Comics launched Backstage Pass in December 2013, the use of Tumblr may have been influenced by a desire to reach teenagers and young adults enticed by a teenage female superhero. A non-Marvel survey conducted in early 2013 found that 61 percent of teenagers aged 13 to 18 regularly use Tumblr, while 55 percent regularly use Facebook (Lynley 2013), a preference that tracks to all other social media platforms. Respondents aged 19 to 25 also preferred Tumblr over other platforms (Lynley 2013). A move by the digital comics platform ComiXology might have also influenced this decision.

[5.3] In July 2013, ComiXology transitioned from an in-platform blog to Tumblr. Later that year, ComiXology CEO David Steinberger shed light on what likely incentivized ComiXology's transition to Tumblr: "a new customer is emerging: she's 17–26 years old, college-educated, lives in the suburbs, and is new to comics. She prefers Tumblr to Reddit. She may have never even picked up a print comic" (quoted in McGarry 2013). Steinberger not only accounts for the concentrated teenage demographic of Tumblr but conceives of it as a space oriented toward females and their potential preference for consuming digital comics. Just as Julie Wilson and Emily Chivers Yochim describe Pinterest as a "highly feminized platform" with the potential to impact "how women move through and feel everyday experiences" (2015, 233), Steinberger similarly perceives of Tumblr as a feminized space suggestive of how some women move and feel their way into online comics culture.

[5.4] In the run-up to the publication of Ms. Marvel #1, Marvel Comics used Tumblr to create and strengthen audience ties. In doing so, the company provided a space ennobling of oft-marginalized identity characteristics that do not necessarily conform to tropes, iconography, and conventions commonly associated with superhero characters and texts. While Tumblr's unique social affordances are an integral component to the ways these nonconformist possibilities took shape for Backstage Pass fans, the Ms. Marvel character and comics text are also key to understanding the way in which interactions on this Tumblr site serviced the visibility of traditionally marginalized fans.

[5.5] The Ms. Marvel character and text enable fans to both identify with Ms. Marvel and her identity vectors and also disidentify with normalized conceptions of a superhero's visual, narrative, and cultural elements. Landis notes the overlap of Ms. Marvel fan engagement with the comic book, character, and creators in ways "meaningful to their own subject formation" (2016, 43), especially when Amanat prompts engagement with reapproprations of Ms. Marvel imagery.

[5.6] This prompting is evident—and perhaps more deliberate—in the first post on Backstage Pass on December 27, 2013. The post features the cover to the impending first issue in which Kamala is portrayed from the waist up, with the top edge of the page cutting off her eyes and the upper portion of her head. Accompanying text describes the intent of the picture to capture critical aspects of her identity: "note the bracelet with her name written in Arabic, while the scarf around her neck is representative of her culture and faith." Similarly, the first line of a running header atop the blog notes "'Ms. Marvel' is the first Marvel comic to feature a Muslim super heroine."

[5.7] Marvel Comics' discourse suggests that the company conceived of Tumblr as readily equipped to attract female fans and similarly believed the character's racial, ethnic, and religious attributes were a critical aspect of how the character's depiction on Backstage Pass could enable a platform comprised of diverse voices. The image's religiously freighted signifiers highlight Ms. Marvel's "complex and unstable entanglements of gender, religion, and identity" (Khoja-Moojli and Niccolini 2015, 25) and work in combination with the accompanying text to ensure that racial, gender, and religious aspects are foregrounded as significant identity markers. The foregrounding of such imagery plays a critical role in reproducing and resisting "dominant constructions of Muslims, Islam, and immigrants in the United States" (Khoja-Moojli and Niccolini 2015, 25). Ms. Marvel's visual iconography similarly reproduces and resists presiding depictions of Muslims, Islam, and vectors of gender and race entangled therein, aspects that Marvel consciously heightened through Backstage Pass.

[5.8] A notable example is Sana Amanat's inducement for Backstage Pass fans to help spread the word about the upcoming release of the first issue by approximating their own identity with that of the fictional Kamala Khan. In a post entitled "I am Kamala Khan. So Are You," dated January 20, 2014, Amanat holds a print copy of Ms. Marvel #1 over part of her face so that her eyes and the top of her head complete the bodily aspects of Kamala omitted from the cover image (figure 1). A brief note accompanying the image asked followers to submit similar pictures by February 5, the day of the series' launch. In this way, Marvel explicitly asked its fans to assert their fandom. It also implicitly required fans to complete the image of Kamala Khan by using the print comic in ways that highlight gender and racial markers for fans and character alike. These fans were also given another implicit requirement: perform labor on behalf of Marvel Comics. Given that many companies, including Marvel Comics, increasingly rely on unpaid fan labor to spread their brand and suffuse it with value (Jones 2014), complying with the "I am Kamala Khan" initiative meant that fans were undertaking promotional labor by directly promoting the Ms. Marvel comic itself and indirectly promoting Marvel Comics as a brand actively engaged with issues of diversity across content, intellectual property, and audiences.

Figure 1. Sana Amanat completes the cover of Ms. Marvel #1.

[5.9] Fan reactions to the "I am Kamala Khan" request exemplify Fiske's notion of "enunciative productivity" (1992, 38) of fandom whereby the enunciating capacities of fans leverage socially specific forms of communication to generate and reinforce discourse unique to their fandom community. When Fiske notes that many fans choose particular fandoms based on "the oral community they wished to join" (1992, 38), he implicates enunciative productivity as not just an ancillary function of fandoms but a capacity highly determinative of how and why fans cohere around a cultural object.

[5.10] Many fans responding to Amanat's request chose to enact their enunciative productivity on Tumblr, Instagram, and Twitter. On February 5 2014, Twitter user @ksreenivasan24, for example, posted a picture of a female completing the Ms. Marvel cover, while a male also poses with a copy of the Ms. Marvel comic so that the entirety of his face is visible. On February 17, 2014, on Tumblr, @carolineballardreports posted a picture of a woman identified as Lena Shareef completing the Ms. Marvel cover (figure 2), alongside subsequent photos of Lena interacting with the comic and a photo from earlier that same day of Lena standing outside New York City's Midtown Comics (figure 3). Recalling Tumblr's ability to connect personal lived experiences to larger cultural narratives, we see in this post the way @carolineballardreports used Tumblr to enunciate Lena's personal experience with the Ms. Marvel comic and then, by virtue of approximation to the Midtown Comics picture, connect this personal experience with cultural spaces for consumption and interaction, to not only become Kamala Khan, but to also become a knowledgeable participant in comics culture.

Figure 2. A fan replicates Amanat's pose with Ms. Marvel #1.

Figure 3. Outside Midtown Comics in New York City.

[5.11] These enunciative productivities find accord with Kristen J. Warner's recent work on black female fans of the television show Scandal (2012–) for whom "producing content is a necessary act of agency" (2015, 34) as they seek visibility in cultures that conflate fan identity with racial whiteness. Similarly, at Marvel's behest, fans of Ms. Marvel strove to make themselves visible within a comics culture prone to code normavitity as masculine and white. Their heterogeneous use of platforms also suggests possibilities for fandoms to stake out territories on Tumblr and elsewhere that affirm multitudinous identity expression and resist normativity as a hegemonic construct. As previously noted, Tumblr and fandom operate within liminal spaces between, respectively, production/consumption and industry/audience, suggesting that movement both within and external to spaces such as Backstage Pass may occur with greater fluidity, especially as it corresponds to the more fluid nature by which identity is understood, enunciated, and rendered visible across this community of fans and their spatial permutations.

[5.12] These enunciative capacities also help undermine presiding conceptions of fans as apolitical and disinterested in puncturing oppressive normativity (Warner 2015, 36). In this way, Backstage Pass affords opportunities for fandom as an enterprise oriented not just around a character or brand; it readies emergent perceptions of who a fan is, what she looks like, and how she practices her fandom. For Marvel Comics, however, this enlargement also presents an opportunity to inaugurate these fans into preferred industrial practice, particularly as Marvel leveraged Backstage Pass to channel these fans toward the company's preferred spaces for comics consumption.

6. Diversity, politics, and the logics of consumption

[6.1] For Marvel Comics, Backstage Pass affords the company two opportunities to serve its institutional and economic goals. First, the site enables Marvel to grow and diversify its comics-buying audience by sanctioning a space that accommodates diverse identities, fan practices, and technological flexibility. Second, Backstage Pass is a centralized means of channeling this newly emboldened fandom toward comics specialty stores. With very little exception, comics specialty stores are the exclusive point of consumption for serialized periodical comic books. Although many comics initially produced as periodicals are subsequently collected into bound volumes more widely available outside specialty stores, the sales of periodicals often economically underwrite their subsequent collection into bound volumes, necessitating a degree of emphasis on periodical comics for stores and companies alike. For a comics company like Marvel, sales of periodicals have historically been interpreted as indicative of market interest across publishing formats, while, for specialty stores, their near-exclusive domain over the sale of periodicals provides a central part of their allure as consumptive and cultural sites of exchange. Thus, Marvel has a vested economic interest in preserving the overall economic health of the comics specialty market, as sales to these stores are both a source of revenue and an important measure of market interest for subsequent formats.

[6.2] While Marvel could have used the Tumblr site to promote the sale of Ms. Marvel on ComiXology or its own digital storefront, many Backstage Pass posts make no mention of digital comics and instead urge fans toward specialty stores. Examples include a January 10, 2014 admonition to "pre-order from your local comic shop by 1/13/14 to guarantee your copy!"; a February 5, 2014 (the day of the first issue's release) headline that reads "It's Ms. Marvel DAY. You in a comic shop yet?"; and an April 16, 2014, post proclaiming "Patience is a virtue—oh stop it, just get to your comic shops already. It's Ms. Marvel Day once again. Issue #3 is on sale NOW." Despite the seeming lack of promotion for digital comics on Backstage Pass, every purchase of a printed Marvel Comics book is a de facto purchase of the digital comics version, since Marvel Comics includes in all its print issues a redemption code for a digital version of the print comic available through Marvel's mobile application (an initiative in place since 2012). Thus, emphasizing physical comic book stores can be interpreted as either Marvel prioritizing direct market stores and print comics over digital counterparts or, instead, as an attempt to incentivize fans to establish a footprint in Marvel's digital ecosystem by situating the print comic as a value-added entry point into digital comics consumption and readership. These two possibilities are also not necessarily mutually exclusive, as leveraging long-standing distribution channels to augment the scale of audience investment and perceived value is a common practice in many industries beyond the comic book industry or, for that matter, nonmedia industries. While Marvel's exact intentions are subject to speculation, less susceptible to such speculation is evidence of Ms. Marvel's success in both print and digital: one week after the first issue's publication, Ms. Marvel #1 was Marvel's best-selling digital title for that week (based on rankings on Marvel's digital storefront) and the first print issue was ultimately reprinted six times.

[6.3] Shortly after this printing, reports indicated that digital versions of Ms. Marvel still outpaced sales of its print counterpart. By November 2014, comics journalist Heidi MacDonald noted Marvel's "established talking point that Ms. Marvel is a digital hit" (2014). Indeed, after the initial digital sales success of Ms. Marvel, utterances of this success were often folded into broader discourses. Marvel publisher Dan Buckley described Ms. Marvel as a "legitimate top-selling title for us in all channels" (ICV2 2015). Digital and print, in this and many other instances, were often collapsed into a pithy talking point that conflated their successes.

[6.4] MacDonald speculated that the repetition of this talking point represented "perhaps a teensy hint at why diversifying the audience is not a dirty word any more" (2014) for Marvel Comics. Just a few months later, Buckley seemed to verify this sentiment through an endorsement of Axel Alonso and his efforts to be "very aggressive in making sure that we have more female lead characters, that we have a more diverse palette of ethnicity in the books" (quoted in ICV2 2015). He described comics conventions and social media as feedback mechanisms that provide a sense of an increasingly diverse readership. On that front, Ms. Marvel's sixth printing spoke to the "growing number of women and supporters of multi-cultural storylines who are entering the fold" (Romano 2014).

[6.5] By mid-2016, Ms. Marvel's increasing visibility and success was evident in the continued publication of her comic, the manifold formats in which the comics were published (periodical, trade paperback, and deluxe hardcover editions), her inauguration into the Avengers and Champions teams (and her continued presence in their respective comics), and her appearance in the animated Avengers Assemble television program. As of this writing, the last Backstage Pass post is dated August 4, 2016. This post sought to align Kamala Khan's identity components with American virtues of inclusivity, openness, and plurality, and further implore fans to vote in the upcoming presidential election. The post features the cover for Ms. Marvel #13 (Vol.2) in which Kamala Khan strikes an assertive stance set against the backdrop of an American flag. The image "speaks volumes about who Ms. Marvel is and what she stands for" and ends with a reminder that the issue is out in November and therefore a "great reminder to get out and vote."

[6.6] The subsequent results of the electoral college were not likely the intentions of this admonition to vote. In the wake of the election, however, even as Backstage Pass went silent, fans took to Tumblr and elsewhere to assert their identity components in conjunction with Ms. Marvel and in contrast to president-elect Donald Trump's ideologies and policies (particularly the Muslim Ban on entry into the United States). In doing so, these fans replicated the logics of the "I Am Kamala Khan" initiative to not only assert personal and collective dignity along lines of race, ethnicity, and gender, but to also foreground Ms. Marvel as a character oppositional to the new political climate.

[6.7] While it might seem somewhat paradoxical that fans were both compliant with an initiative instigated by Marvel Comics as a promotional vehicle and later repurposed the initiative to assert civic and cultural politics, such paradoxes are often at the heart of translating fan participation into participatory civic politics. Brough and Shresthova note that fan-generated works transpiring through commercial venues are often both resistant and compliant, but the political significance of these works is the contestation and alterations of cultural codes and discourses so that "resulting content is consumed and reconfigured as a resource for mobilization" (2012). Seen through this lens, tactics used to comply with the original "I Am Kamala Khan" initiative can later be repurposed as tactics of civic resistance. Just as compliance meant asserting identity markers corresponding to Ms. Marvel, the repurposing of these same cultural codes and discourses became the grounds to mobilize contingencies of fans resistant to xenophobic, racist, misogynistic, and anti-LGBTQIA politics brought to the forefront through the election of Donald Trump. If the question of translating fan practices into civic political activity hinges on "how to move from having a voice within a subculture to being heard more broadly in civic and political spaces" (Brough and Shresthova 2012), the repurposing of tactics associated with the "I Am Kamala Khan" initiative demonstrates some headway in bridging politically minded enunciations across fandoms and civic arenas.

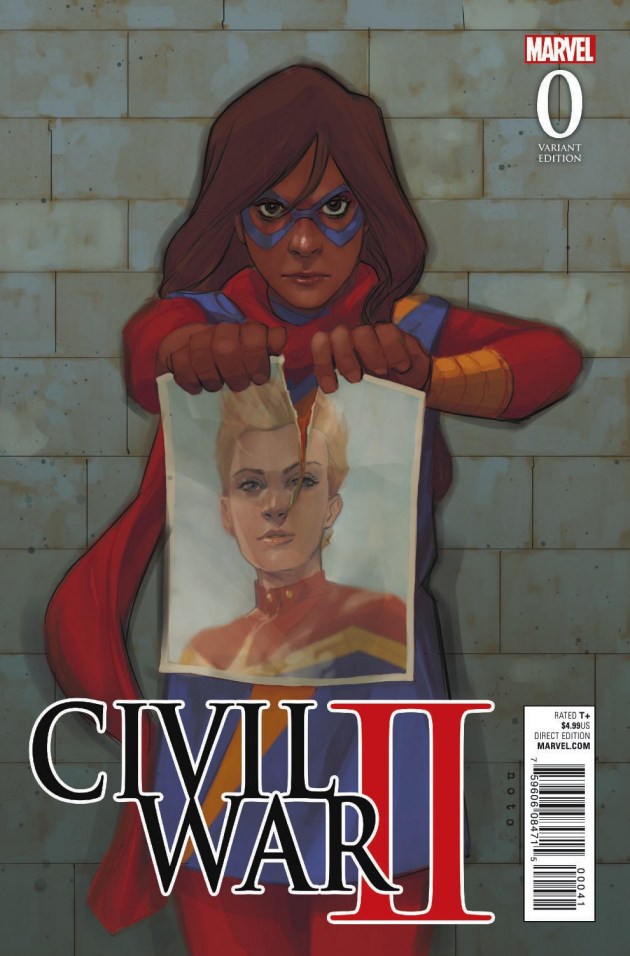

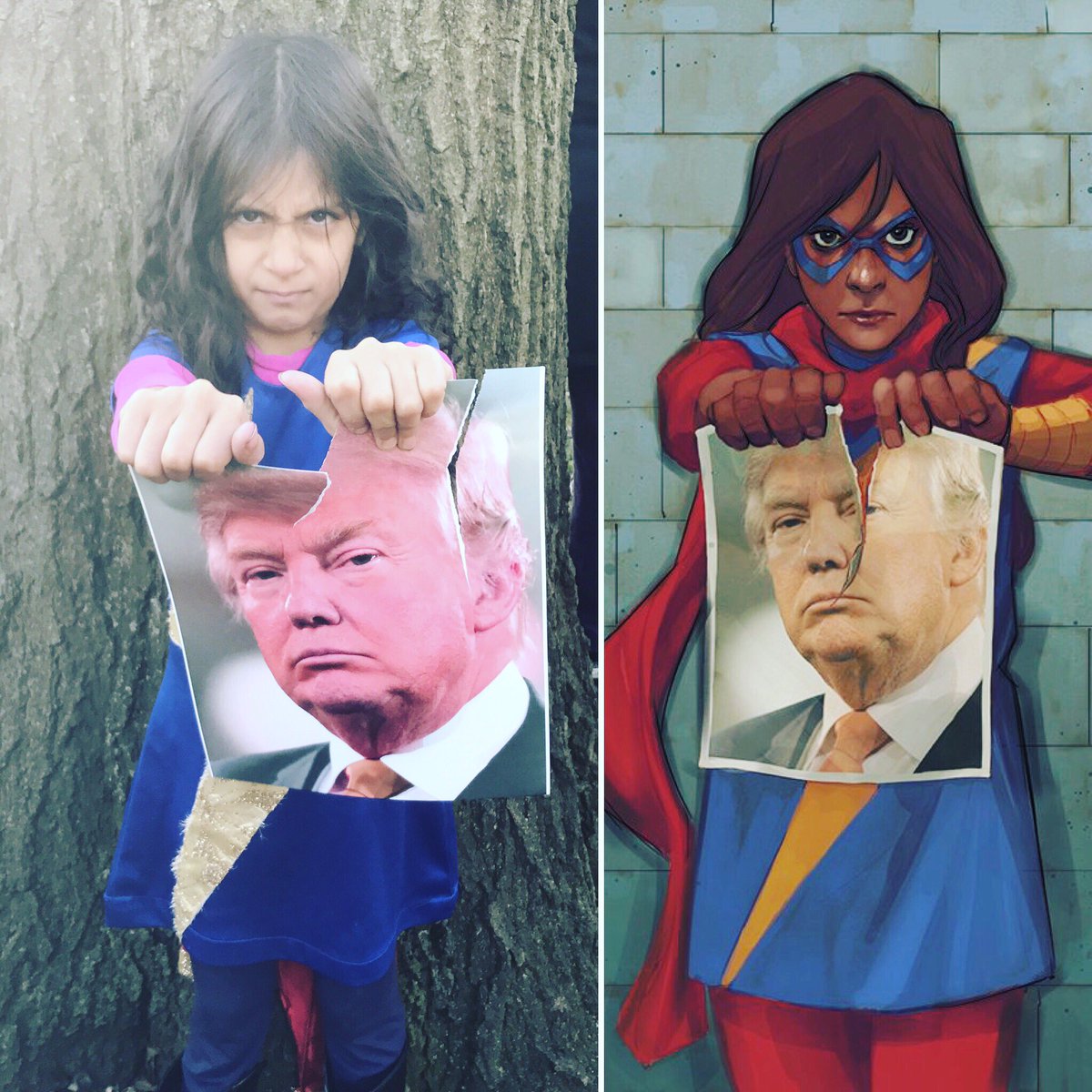

[6.8] Shortly after the implementation of Trump's "Muslim Ban" in late January 2017, comics artist Phil Noto circulated a modified version of his cover art for Marvel Comics' Civil War II #0. In the original, Ms. Marvel stares out from the cover towards the reader as she aggressively rips in half a picture of Captain Marvel (figure 4). In the modified version, the picture she tears asunder is of Trump. The image not only circulated widely on social media, but was one among numerous instances of fans approximating their own identity with that of Kamala Khan in a manner similar to the "I am Kamala Khan" initiative. One prominent example is an image posted by Twitter user @navdeep_dhillon and ultimately used as the header image for a Vox story on Ms. Marvel's newfound status as a resistive icon (Romano 2017). In this image, the modified Noto image is juxtaposed with a picture of a real-life girl ripping apart a photo of Trump (figure 5). Her facial expression and dress are similar to those of Ms. Marvel, and similarly code as nonwhite. Another similarity fans such as these share with Ms. Marvel is her love of fan fiction. As previously noted, within the context of the diagetic shared Marvel Comics universe, Ms. Marvel creates Avengers fan art and stories. In the first issue of Ms. Marvel, Kamala's fan fiction comic sees the Avengers defeat a space creature threatening Planet Unicorn (Wilson 2014). In this way, Kamala shares with Ms. Marvel fans a capacity to reimagine characters and circumstances, notably in the face of dominant narratives. When Ms. Marvel fans are "scripted toward similar identifications and reimaginings" (Landis 2016, 36), they do so as a way to justify their identity attributes and fan preferences with the intent of counteracting dominant narratives, be it civic political narratives that correlate racial and religious signifiers with threats to national security or narratives within fan cultures that downplay the significance of fannish participation based on gendered and/or racial conceptions.

Figure 4. Cover to Civil War II #0 showing Ms. Marvel ripping a picture of Captain Marvel in half.

Figure 5. Figure 5. Life imitates art: Donald Trump replaces Captain Marvel on the cover of Civil War II #0; and a young girl imitating Ms. Marvel tears the photo of Donald Trump.

[6.9] Within all media industries, there are ongoing struggles between fans and institutions, including the incorporation of fannish tastes into institutional market strategies and fans' tendencies to "excorporate" these institutions' products (Fiske 1992, 47). The fan excorporation of Ms. Marvel from industrial text to fandom pastiche to politically charged icon exemplifies the possibilities for fandoms to foster a sense of community, values, and practices that produce tangible outcomes in civic spheres, industrial markets, and lived experience. Looking ahead, one of the challenges facing Marvel Comics, its fans, and the broader marketplaces of ideas and commerce is the extent to which a fandom such as that engendered through Backstage Pass aligns with long-standing business practices and the capability of Marvel to shift its corporate mechanisms to meet the desires of emergent audiences.

7. Conclusion

[7.1] In an April 2017 interview, Wilson spoke to this dilemma, describing comics culture as split into two broad sectors of audienceship and the comics industry at large as one hesitant to "recognize that these two audiences might want two very different things out of the same series. They don't shop in the same places, they don't socially overlap, and their tastes might not overlap" (quoted in Tolentino 2017).

[7.2] As alluded to by Wilson, the bifurcation of comics culture into two prominent audienceships cuts across spaces of consumption, sociality, and cultural identification. While Warner cautions that producers of media texts are often "ill prepared to discuss and negotiate bodies unlike their imagined demographic" (2015, 37), one legacy of Backstage Pass and the success of Ms. Marvel is their intertwined role in motivating Marvel Comics to continue reimagining its superheroes with an eye toward gender, racial, and cultural diversity that expand upon the ways Marvel traditionally imagined its demographics. To that extent, the company's 2017 anthology series Generations consists of ten issues featuring classic depictions of superheroes alongside their contemporary counterpart, including an issue pairing Kamala with Carol Danvers, who previously assumed the mantle of Ms. Marvel. Many of these contemporary counterparts reflect Marvel's attempts to broaden the identity components of its superheroes, such as the female Jane Foster taking over as Thor; African American Sam Wilson (formerly the Falcon) becoming Captain America; Korean American Amadeus Cho becoming The Hulk; and African American female RiRi Williams becoming Ironheart, the primary Iron Man stand-in.

[7.3] The sales success of Ms. Marvel across multiple formats, alongside the proliferation of Kamala's imagery across horizontally integrated mass-market ventures (i.e., Avengers Assemble cartoon; merchandising), validates for Marvel Comics the economic viability of Ms. Marvel as both a character and brand and also gives the company leeway to claim an aptitude for creating characters that resonate with audiences increasingly composed of greater gender, racial, and ethnic plurality. The mobilization of Ms. Marvel as a signifier of personal identity, cultural belonging, and political resistance across online and offline spaces both reinforces corporate objectives and extends beyond the boundaries of institutional ideology, as the Backstage Pass showcases the possibilities for Tumblr and other digital spaces to serve as a proxy for overlapping industrial and cultural interests, while continually negotiating the points at which unaligned vectors collide and repel amidst shifts in institutional, social, and political climates. In this way, the formation of the Ms. Marvel fandom on Backstage Pass also orients to circumstances in which the affordances of digital spaces are, alternately, a flowering for fandom identity and expression, the channeling of their labors toward commodified objectives, and the precarious nature of maintaining corporate-sanctioned spaces amidst evolving market, institutional, social, and political conditions.