1. Introduction

[1.1] Universal Orlando's Wizarding World of Harry Potter (WWoHP) technically could be classified as a themeland, an area conveying a single idea or theme within a larger theme park (Lukas 2013, 80). However, common usage, including much of Universal Orlando's own publicity material, refers to WWoHP as a theme park. As of 2017, major components of WWoHP include Hogwarts castle (home of the Forbidden Journey ride) within Hogsmeade. The Hogwarts Express train ride connects to Harry Potter's version of London, which leads to Diagon Alley, which includes Knockturn Alley and the Escape from Gringotts ride. Hogsmeade, Diagon Alley, and Knockturn Alley all include shops and opportunities to cast "spells" using interactive wands sold within WWoHP. Specific locations require specific movements for RFID chips to trigger practical special effects that produce material changes in the environment, such as splashing water and moving various physical props. Theme parks such as WWoHP offer material interfaces that engage multiple senses to facilitate immersion in imaginary story worlds. Thus, they present new aspects of both fan tourism and of material fan practices to explore.

[1.2] First, a few definitions are in order. Story worlds are defined as "places people can visit and live in for a time" (Lancaster 2001, 163). Alternative terms include "'subcreated worlds,' 'secondary worlds,' 'diegetic worlds,' 'constructed worlds,' and 'imaginary worlds'" (Wolf 2012, 13), media worlds, and many others. Such "imaginary worlds invite audience participation in the form of speculation and fantasies, which depend more on the fullness and richness of the world itself than on any particular storyline or character within it; quite a shift from the traditional narrative film or novel" (2012, 13). Using media studies as a theoretical framework shifts the "focus on the worlds themselves, rather than on the individual narratives occurring within them or the various media windows through which those narratives are seen and heard" (2012, 12). Using fan studies as a theoretical framework allows exploration of fan desires to access those worlds, and also exploration of some of the material practices, such as interfaces, fans use to access those worlds.

[1.3] Kurt Lancaster's conception of the interface used within media studies and fan studies scholarship offers a productive means to examine theme parks. "The interface is a concrete material object that helps open the door to another's imaginary universe. It makes concrete the imaginary" (Lancaster 2001, 32). Through interfaces such as "toys, games," and other material objects, such as collectible card games, "the imaginary, the virtual images of film and television, can now be touched and manipulated," offering "haptic dominance to the previously singular scopic representation of fantasy" (2001, 103). Interfaces involve touch, not just sight. Potentially, interfaces allow fans to see, hear, touch, taste, smell, and interact with story worlds. It is important not to confuse Lancaster's use of the term "interface," a material object allowing physical interaction with story worlds, with computer, new media, or other electronic interfaces that allow virtual interaction with story worlds. Such virtual interfaces are more similar to the "various media windows" used to access "an imaginary world" (Wolf 2012, 9), such as video games, books, films, and television.

[1.4] Immersion ranges from "the physical immersion of [the] user, as in a theme park ride or walk in video installation; the user is physically surrounded by the constructed experience" to "conceptual immersion, which relies on the user's imagination; for example, engaging books…are considered 'immersive' if they supply sufficient detail and description for the reader to vicariously enter the imagined world" (Wolf 2012, 48). This article specifically uses Lancaster's definition of immersion, because of its relevance to material interfaces:

[1.5] Immersion is the process by which participants break the frame of their actual "everyday" world, allowing them to interact in some way within the fantasy environment. An interface provides this immersion. When people engage the interface, the imaginary world or universe represented by the environment envelops the real-world perspective, and, as a consequence, players become immersed in the fantasy universe. (Lancaster 2001, 31)

[1.6] Via multisensory material interfaces, theme parks enable not only the most basic physical immersion of rides or attractions but also conceptual immersion in story worlds that inspire those forms of entertainment.

[1.7] The material environments of theme parks offer entry to and interaction with imaginary story worlds. Within theme park design, "all of the material things—the streets, the bricks, the tables and chairs, the lights, the fountains, etc.—that make up the themed or immersive space" can be "used to tell immersive stories and/or create specific feelings or moods in guests" (Lukas 2013, 208). In contrast to the visual or aural emphasis of reading or watching media texts, or fan fiction or fan vids inspired by them, visitors are able to immerse themselves within physical versions of story worlds that engage multiple senses simultaneously: not only sight and sound, but also touch, taste, and smell. Both fan studies and current scholarship on theme parks emphasize active participatory conceptions, countering popular oversimplifications and misrepresentations of both audiences and theme park visitors as passive spectators or consumers. For example, corporate-created and -controlled theme parks frame and market fan activities to encourage consumption. Yet fans and other visitors, active as always, often use such merchandise as additional interfaces to participate in WWoHP's attractions and to facilitate immersion in the wizarding story world. In WWoHP, interactive wands enable visitors to create specific physical "spell" effects in specific locations via technology. These wands and their spells serve as a synecdoche for the story world's magic, assisting immersion.

[1.8] Like spells and wands, the narratives that inspire many theme parks are fictional and do not exist in the everyday world. Thus, "real" and "authentic" obviously become problematic terms. Fan studies scholarship offers context-specific definitions, such as the use of "'authentic'…to denote the official licensing of WWoHP, and…to capture a visceral connection many fans…feel to the wizarding world" (Gilbert 2015, 25). For theme park design, authenticity involves no truth claims, only perception: "a space that seemed real or believable to the guest" (Lukas 2013, 238). Environments within theme parks seem "real" if they offer accurate recreations of film props and sets to create a sense of immersion within these recreations of fictional worlds. Fans are willing to suspend disbelief when interfaces such as theme parks create a sense that this is what it felt like to watch the movies or to read the books. The story world already captures the fan's imagination, and it feels real enough inside their mind to suspend disbelief. It offers conceptual immersion. If a theme park captures what a fan imagines this story world to be like, then interacting with a theme park's physical manifestations of this story world makes that story world seem more real or authentic. In contrast, the framing device for the Warner Bros. Studio "Making of Harry Potter" tour in London foregrounds the fictional nature of the story world. Publicity material invites visitors to see sets, props, and costumes used to make the films, and learn how special effects create the illusion of magic. Meanwhile, the framing device of WWoHP encourages the suspension of disbelief. Instead of seeing Diagon Alley sets in a movie studio, promotional materials characterize WWoHP visitors as walking down Diagon Alley itself, and performing their own magic by casting spells with interactive wands.

[1.9] Suspension of disbelief, "the willingness to accept the world of the imagination as real…which allows [fans] to renew and…extend their belief in the imaginary beyond the confines of the book or film" (Reijnders 2011, 241) is part of the process of immersion, as well as an aspect of fan tourism. The field of fan tourism allows for discussions of extending the suspension of disbelief required for enjoying fiction into the physical world. Fans suspend disbelief not only while reading books or watching screens but also when they experience a theme park's rides and attractions: physical manifestations of story worlds previously encountered in books, films, video games, and other media windows. Not only a fan's mind but also a fan's body experiences immersion in a story world via such suspension of disbelief: both conceptual and physical immersion. Now a story world tastes, smells, and otherwise feels real to a fan's physical senses as well as within their imagination.

[1.10] The story worlds of theme parks do not necessarily have an essential connection to films or other mass media, or even to branded versions of fairy tales such as those which appear within Disney theme parks. For example, with Sinbad's Bazaar and Poseidon's Fury, Universal Orlando's Lost Continent draws upon ancient legends and mythology instead of upon licensed mass media retellings of those stories. Both the former Wet 'n Wild Orlando and the forthcoming Volcano Bay are themed simply as water parks. Versions of famous cities such as New York, Hollywood, and San Francisco receive far less active publicity than their licensed neighbors, Harry Potter's London and The Simpsons attractions in Springfield. However, as part of our media-saturated culture, theme parks often draw their "inspiration from particular films, exploiting characters created for the movies, and even functioning after the fashion of our popular films" (Telotte 2011, 171). Theme parks "are the multi-dimensional descendant of the book, film, and epic" in which "rides are mechanisms designed to position the visitor's point of view, much as the camera lens is aligned, moving riders past a series of meticulously focused vignettes to advance the narrative" (King and O'Boyle 2011, 6). However, theme parks have changed their emphasis from rides perceived as "spectacles where guests passively view wonders" (Baker 2016, ¶6.1), letting "a story unfold around them" to understandings of "rides…featuring interactivity and immersion," allowing visitors active participation "or even taking the lead role in the adventure" (2016, ¶1.2). Theme parks function as storytelling devices—material interfaces simultaneously engaging multiple senses to immerse visitors in a variety of story worlds.

2. Fan tourism and theme parks

[2.1] Fan tourism scholarship offers useful insights into how visitors interact with theme parks. Rather than detailing the nuances of fan tourism, fan pilgrimage, media tourism, pop culture tourism, teletourism, literary tourism, and other related phenomena, this article focuses on commonalities of these experiences, referred to generally as fan tourism for the sake of internal consistency. People engaging in such tourism report a sense of being "closer to the story" or "making a 'connection'" (Reijnders 2011, 242). They also describe "traveling into your imagination in real life" or a desire "to 'touch the feeling' of [the story] in a bodily, all-encompassing way" (Erzen 2011, 11), with obvious parallels to immersion via material interfaces. Fans characterize visiting a location mentioned in a story world as "not their first encounter with the [place], but rather a renewed encounter, the realisation of a journey which they have already taken many times in their imagination" (Reijnders 2011, 238). Although visitors engage in "a rational comparison of reality and imagination," they emphasize "the intention of deepening their emotional connection with the story…Both modes are based on a tangible experience of the local environment. Being right there, present at the location, rather than experiencing it at a distance via the media" (2011, 242). Visitors "experience the story anew thanks to these sensory stimuli" (2011, 246). Material interfaces offer different pleasures than experiencing story worlds via media windows. For Twilight fans, the actual town of Forks offers a focus "for fans' collective fantasy that they might momentarily" enter the story world (Erzen 2011, 12). WWoHP offers a similar fantasy, the playful suspension of disbelief that turning a corner could lead from a theme park into a magical wizarding world. It is an interface offering immersion in a story world.

[2.2] Theme parks offer travel into specially constructed imaginary locations such as Hogwarts, Hogsmeade, and Diagon Alley, or to versions of real places such as New York, Hollywood, San Francisco, and London as filtered through media texts and the popular imagination. For some, they offer more affordable alternatives than travel to existing physical locations where stories are set or filmed, such as Transylvania or London, or Vancouver or New Zealand. Yet fan texts "have been rendered largely invisible in tourist debates due to the notion that since fantasy and science fiction texts are based on imaginary spaces that they can possess no real-life geographical referents" (Hills 2002, 147). Nonetheless, fans still exhibit "the extratexual impulse to inhabit the world of the text" (2002, 166). Settings, filming locations, and theme parks all offer geographical referents to facilitate such visits. Some of this fan desire to explore is due to hyperdiagesis, or "the creation of a vast and detailed narrative space, only a fraction of which is ever directly seen or encountered within the text, but which nevertheless appears to operate according to principles of internal logic and extension" (2002, 137). Both the story world and Diagon Alley seem internally consistent and "real" enough to offer the fantasy that the street extends much further than the buildings described in books or glimpsed on screen. Fans enjoy opportunities to explore additional details of this and other story worlds, whether via material interfaces such as WWoHP or the additional media windows offered by fan practices such as fan fiction or fan vids.

[2.3] The same tendency is noted from early fan studies scholarship onward. Fans enter a "realm of the fiction as if it were a tangible place they can inhabit and explore" (Jenkins 1992, 18) and are "active producers and manipulators of meanings" (1992, 23). Even if elements of these imaginary story worlds are built in the everyday world, "these objects necessarily remain divided, split between physical instantiation and an immaterial story world that is affectively or mnemonically carried for the fan" (Hills 2014, ¶2.11). Although "the mediated 'reality'…and the reality of the physical space or place…cannot be fused…it is rather the permeable boundaries between these two realms which are redefined and recontextualised by cult geography" (Hills 2002, 146), which is defined as sites associated with beloved narratives or story worlds such as filming locations or settings for stories (2002, 144). Such places facilitate "fantasies of 'entering' into the cult text, as well as allowing the 'text' to leak out into spatial and cultural practices via fans' creative transpositions" (2002, 151). Theme parks like WWoHP occupy such liminal spaces. They also offer interfaces by means of which fans are able to immerse themselves in story worlds. Indeed, "theme parks have long been in the world-building business. They offer us a chance to immerse ourselves within the fiction, to have a total sensory experience of the places of our imaginations" (Jenkins qtd. in Lukas 2013, 247).

[2.4] Fan studies scholarship already addresses familiar storytelling techniques such as fan fiction or fan vids (Jenkins 1992). Created by fans for fans, these are more obvious forms of active participatory culture than theme park visitors who physically and conceptually immerse themselves within corporate-created and -controlled versions of story worlds drawn from favorite texts. However, WWoHP, Disney theme parks, and many others offer multisensory opportunities to actively engage with familiar story worlds. In Disney theme parks, rides such as "Mr. Toad's Wild Ride and Snow White's Adventures…used material from the films to create what were essentially new stories" (Rahn 2011, 89). Rides such as Escape from Gringotts and the Forbidden Journey in WWoHP continue this tradition of using familiar material to expand existing narratives. Established settings and monsters appear, including replicas of film versions of dragons and giant spiders. Actors from the films deliver new lines to lend a sense of authenticity to the creation of new narratives. Familiar characters address those on rides as Muggles, people unable to use magic. Although Bellatrix Lestrange and Voldemort never encounter Muggles in the wizarding bank on screen or in the books, their new dialogue and actions in the Escape from Gringotts ride are consistent and believable. Characters' dialogue positions the ride's events within existing narratives from the books and films. These framing devices contribute a sense of authenticity to new stories. Reproductions of such familiar elements enable these rides to function as new narratives for fans. Such aspects of theme park design invite every person on these rides to participate as a character in the story, the "you" addressed by Voldemort and others. It is an established storytelling device to address an urge for interactivity and immersion, as is the first-person perspective.

[2.5] From its earliest examples, fan studies scholarship consistently emphasizes the active role of fans specifically and audiences in general. It thus offers a useful theoretical framework to examine theme parks. Fans are not "simply an audience for popular texts; instead, they become active participants in the construction and circulation of textual meaning" (Jenkins 1992, 27). Indeed, "there are no such things as passive consumers" (Jenkins qtd. in Lukas 2013, 246). Likewise, making "theme parks…sites for…hypermediated play and participatory culture" positions "guests and fans" as "the marketers, interpreters, culture creators, heroines, heroes" (Baker 2016, ¶6.1). For example, the Men in Black Alien Attack ride casts visitors as new recruits, shooting at villains and competing against other visitors for the highest score. There are rumors that future additions to WWoHP will incorporate similar interactivity (Shapiro 2016). These rumors are based on Universal City Studio's application for a patent for a

[2.6] wizard-themed game where guests can compete with each other or even work together to accomplish tasks by using character wands to score points in puzzle rooms where the actions that the players take within each scene or puzzle change the environment and allow different paths to be activated or different physical effects to take place. (Harrington 2016)

[2.7] Visitors will be active participants, characters whose choices and actions define the characteristics and perhaps even the route this ride will take. Modern-day "theme parks are…designed as much as evocative spaces onto which fans may project their own fantasies as rides which take them through a directed path" (Jenkins qtd. in Lukas 2013, 246). As with rides in which familiar characters address visitors, theme park design likewise invites "you" to actively participate as a character in the story world, encouraging interactivity and immersion.

[2.8] A theme park functions by "evoking impressions of places and times, real and imaginary" (King 2007, 837). In other words, it offers a connection to story worlds. Although a theme park visit "averages eight hours…as little as ten or fifteen minutes" of that time is "spent on rides." Indeed, it is possible to have "a theme park experience without ever setting foot on a ride," instead viewing "architecture, design, animated and live performance, video, sound and music, light and water technics." Simply walking "within and among the artfully landscaped themed 'worlds'" can be enjoyable (King and O'Boyle 2011, 7). This enjoyment is planned carefully. At Disneyland, a 20-foot berm blocks the view outside because Walt Disney did not "want the public to see the real world they live in while they're in the park. I want them to feel they are in another world" (qtd. in Sklar 1969). Within Diagon Alley at WWoHP, building facades block out the view not only of the world outside, but also any sight of the rest of the park, allowing even more complete immersion within the wizarding world.

3. Interfaces: Exploring the wizarding world, wands at the ready

[3.1] Furthering that immersion, wands, robes, foods, beverages, environments, and other concrete objects within WWoHP function as interfaces, allowing fans to physically interact with and thus experience aspects of a story world. Interface objects such as magic wands offer "concrete physicalization of the fantasy world" (Lancaster 2001, 83) and "represent the imaginary…for no such objects actually exist" (2001, 17). Interfaces include "material objects," through which "participants interact with the environment" and thus "experience the fantasy in a certain way" (2001, 32). In WWoHP, interactive wands offer illustrative examples of interfaces. Promotional material encourages fans to purchase interactive wands, offering them opportunities to cast "spells" via technology. Yet such merchandise does not limit fans to supposedly passive roles as consumers. Instead, interactive wands enable active participation via material interfaces. Instead of only seeing wands on screen, now fans can touch, select, and wield wands of their own in WWoHP, then take these interfaces home with them as souvenirs of their trip into this story world. In addition to character wands seen on screen, visitors also can choose "unclaimed" wands created for the park itself. Promotional materials and costumed store personnel both reference the story world concept "the wand chooses the wizard" to encourage visitors to wave display models or to personalize their wand by choosing one linked via the Celtic tree calendar with certain character traits or important dates such as birthdays or anniversaries.

[3.2] Selections made, fans can wave interactive wands in specific patterns so their RFID chips trigger specific effects at specific locations. Spells include activating a mermaid fountain that can squirt people with water, starting and silencing the singing of shrunken heads, and prompting suits of armor to assemble or collapse. Each spell involves practical special effects to produce material changes in the environment, rather than virtual effects or superimpositions that must be viewed on a computer or smartphone screen, as in augmented reality games such as Pokémon Go (2016). More importantly, both spells and the wands that activate them act as a synecdoche for the story world's magic, further enabling immersion. Wands and spells are parts that stand for the whole: all of the wizarding world and all of the magical effects that cannot fit into a theme park, but exist within fans' imaginations. Since they indicate the existence of a much larger internally consistent story world, they contribute to hyperdiagesis (Hills 2002, 137), allowing fans to fill in the gaps beyond the grounds of a theme park or the pages of a book or the scenes in a film. Multisensory magical effects happen live in the physical environment instead of being confined to sights and sounds on film, television, computer, or smartphone screens. Wands act as interfaces that make theme park environments seem real by contributing to a sense that this is what it felt like to watch the movies or to read the books. Wands and their spell effects facilitate suspension of disbelief and immersion in a story world for both wielders and observers.

[3.3] By using a material interface, an element of a media text "previously viewed from a distance" is removed "from its original context," so "one can now touch and reconfigure it" (Lancaster 2001, 100). Interactive wands allow obvious reconfiguration, as spell effects tip over cauldrons or send a tiny wizard and dragon racing around a miniature Hogwarts castle in a window display. In addition, instead of brief descriptions or glimpses during a few scenes in the books or films, fans now are able to spend hours or days exploring Diagon Alley, Knockturn Alley, Hogsmeade, and Hogwarts, peering closely at all the sights, looking where and when they please, instead of where and when and only so long as an author or director decrees. Furthermore, WWoHP's physicalization of this imaginary environment engages multiple senses, compared to more conventional media texts. Theme park visitors "use all of their senses to interact with" a "themed or immersive space" (Lukas 2013, 102). Such "multisensory and multiexperiential" space more closely approximates "what a real space (or in the case of a re-creation of a fictional world, the imagined space) is like" since the everyday world also "connects with all of the senses" and involves people "in more than one thing" (2013, 107). On the Escape from Gringotts ride, hot air blasts riders when a dragon breathes fire. On the Forbidden Journey ride, water hits visitors when Aragog and other giant spiders spit venom, and cold air accompanies a Dementor's attack. Knockturn Alley is not only permanently shrouded in darkness but also kept noticeably cooler than Diagon Alley, to contribute to the ambience of dark wizardry. Multiple sensory inputs reinforce immersive experiences.

[3.4] Many visible items are meant to be touched—especially merchandise, thanks to the corporate emphasis on consumption. Fans taste and smell butterbeer, chocolate frogs, and other food and drink. To fully enjoy their immersive effects, many of these interfaces must be purchased. Even the sights, sounds, and smells of the park itself, like the roar of the dragon atop Gringotts and the heat from its fiery breath, or the stench of a noxious plant in a window display must be bought, included in the admission price. However, even when fans do purchase items, their choice often is an active statement of identity. Obvious examples include whether fans identify as Ravenclaw, Slytherin, Gryffindor, or Hufflepuff. Which personality traits do fans see in themselves: wise, shrewd, brave, or loyal? Souvenir T-shirts link each House with each attribute. Online stores and displays within the Ollivanders shop also market the "unclaimed" interactive wands via association not only with birthdays or anniversaries but also with personal attributes, such as the birch wand for people with an "ability to see through to the heart of any matter" or ivy for people "with tenacity, stamina and endless patience…strong and determined; they set goals and achieve them." Wand selections thus provide material manifestations of how visitors perceive themselves, or function as physical reminders of important events or aspirational goals.

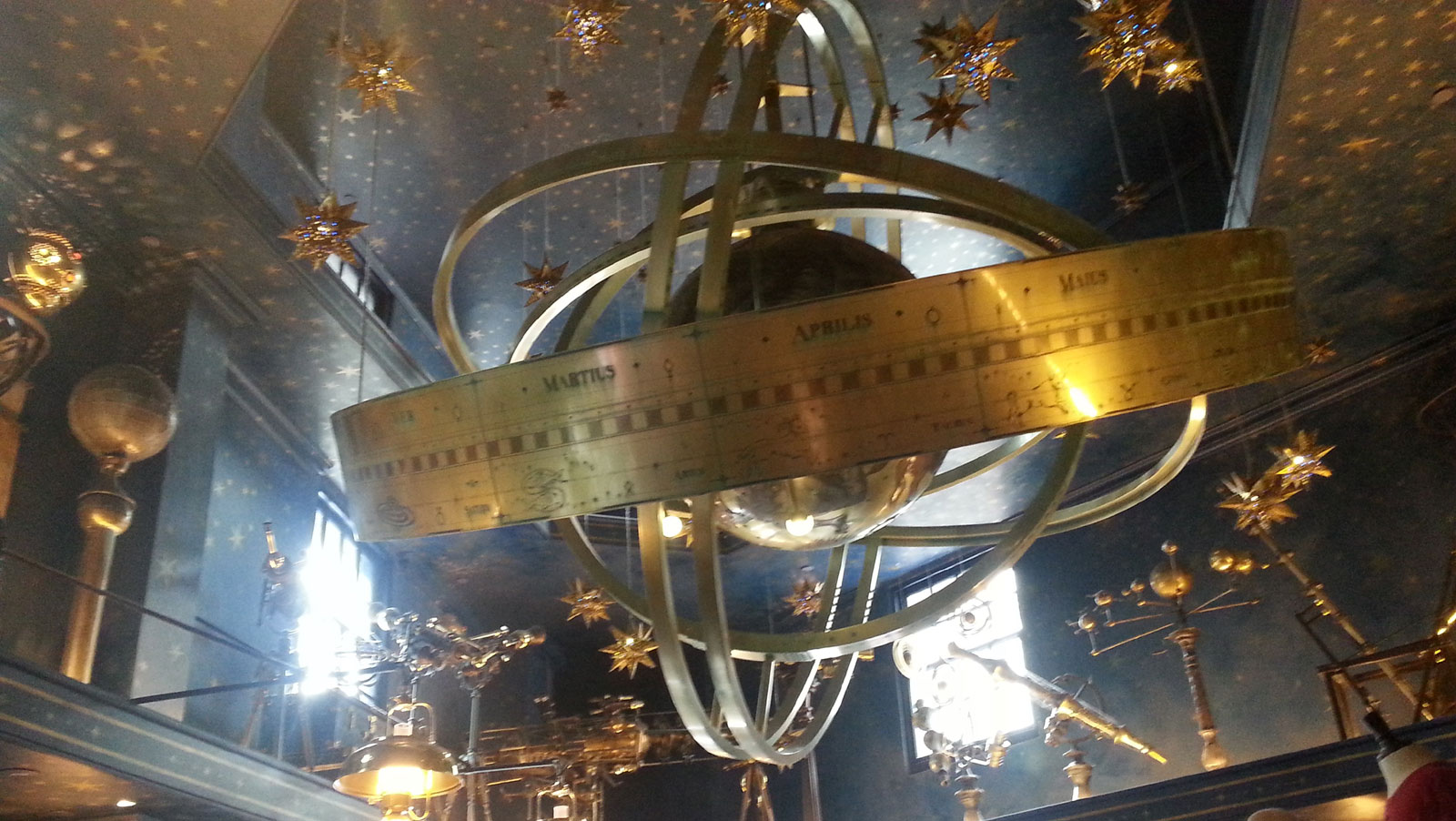

[3.5] Stores also double as exhibits, displaying props and costumes from films as well as souvenirs for sale. For example, in addition to the House robes, sweaters, scarves, and ties for sale in Madame Malkin's Robes for All Occasions store, there also is a display of costumes, including robes for professors Albus Dumbledore, Minerva McGonagall, and Gilderoy Lockhart. These complete outfits are not for sale, although fans can purchase limited elements of some of them, such as Dumbledore's hat. Orreries in Wiseacre's Wizarding Equipment (figure 1), miscellanea in the Borgin and Burkes shop in Knockturn Alley (figure 2), and themed decorations in other shops all contribute to the atmosphere but are not for sale. Many visitors minutely examine and photograph environments without buying any merchandise, enjoying stores as museums, exhibits, or displays of items from the fictional wizarding world. Fans redefine commercial spaces, their stock, and their decor as interfaces to immerse themselves in the story world. Similarly, the line for the Forbidden Journey winds through the gates, greenhouse, hallways, and classrooms of Hogwarts, offering detailed recreations of film sets and props to view during the hours it can take to reach the ride. Yet visitors also have the option to enter a parallel line to view the interior of Hogwarts without boarding the ride, enjoying the environment as an attraction in and of itself instead of solely as a distraction from long wait times.

Figure 1. Fans redefine commercial spaces as interfaces to immerse themselves in the story world. In Wiseacre's Wizarding Equipment, both decor such as orreries, globes, and telescopes, and merchandise such as themed T-shirts on mannequins are framed as part of the story world. [View larger image.]

Figure 2. Many visitors thoroughly examine and photograph displays without buying anything, enjoying stores as exhibits. The Borgin and Burkes shop in Knockturn Alley features more decor than merchandise. Displays include film-related props such as a vanishing cabinet and Death Eater masks, as well as skulls and other miscellanea that contribute to an atmosphere of Dark Wizardry but are not for sale. [View larger image.]

[3.6] Material interfaces allow haptic dominance and the discovery of minutiae that could pass unnoticed or unrecorded onscreen. Umberto Eco discussed the appeal of "a completely furnished world," details of which can be learned and memorized (1986, 198). Lancaster explores fan activities through which "participants can exert a certain amount of control over an environment that once could be experienced only on its own terms" (2001, 163), typically fleeting images on a screen. An urge to explore a story world and master it parallels an urge to explore a theme park and master it. For example, behind-the-scenes tours at Disney theme parks fulfill fan desires for "mastering the space" and insider knowledge (Bartkowiak 2012, 952). WWoHP incorporates out-of-the-way details to reward exploration, such as an ad for the Daily Prophet painted on the wall in a narrow dead-end alley hidden behind Gregorovitch's Wand Shop. Theme park design deliberately incorporates such hidden elements in order to generate a "sense of excitement and discovery in guests who, upon finding one, have the sense of seeing something that no one else has" (Lukas 2013, 234). Design encourages and rewards exploration of and further immersion in a story world. Purchase of an interactive wand includes a map to different locations where you can cast spells, but visitors can choose in which order they proceed and choose whether to skip or to revisit any locations. They also choose whether to compete or to cooperate with any companions. With no corporate-generated framing device, visitors can create their own narratives around why they cast each spell. They create their own performance and define their own participation.

[3.7] Even without one of the maps included with a wand purchase, it is possible to notice runes inscribed on walkways and other visitors waving wands in different patterns at different locations. Although many details can be discovered during solo explorations, fans compile and share information either on Web sites consulted before park visits, or by talking to other fans once on site. Fans thus engage in collective intelligence (Jenkins 2006, 26). Holding interactive wands identifies fellow fans, often prompting strangers to interact with each other. For example, various fans showed me spell-casting locations they said were not listed on official WWoHP maps, and demonstrated the simple wand movements required to trigger certain effects at those hidden locations, such as getting a plant to emit a foul stench or getting eyes to open and track a wand's motion. Later, when another fan noticed me casting a spell at a location he hadn't spotted, I showed him how to view the map's hidden symbols visible only under black light, available in Knockturn Alley. I also passed on the claims I'd heard from other fans about hidden locations not marked on the map. There is a parallel with the liminal space of the convention, where people feel more comfortable greeting and interacting with strangers. After all, they have some degree of affection for this story world in common, so they are not complete strangers. They are fellow fans.

4. Interfaces: Active immersion via consumer merchandise

[4.1] Such interactions with WWoHP's material interfaces illustrate the evolution of theme park rides and attractions noted by Carissa Ann Baker (2016, ¶6.1, ¶1.2), moving from designing for supposedly passive viewing of spectacles to acknowledging and incorporating the desire for active participation. This dovetails with the emphasis from the beginning of fan studies scholarship through to today on fans as active participants, which helps to correct misperceptions of audiences as passive viewers and consumers. With "conventional" visual and aural media, fans "participate vicariously through another's performance. They cannot control the plot or the dramatic action" (Lancaster 2001, 32). Authors, directors, and actors do—although fans can control how they interpret plots and actions, as evidenced by the profusion of fan fiction, fan vids, and other fan works. In contrast, in "immersive performances…participants have to actively engage the site as performers" (2001, 32–33). Immersion permits participants to "break the frame of their actual 'everyday' world, allowing them to interact in some way within the fantasy environment" (2001, 31).

[4.2] However, fans must agree to attend and to interact with physical environments for them to function as interfaces. For example, some fans collect the cards required for an interactive game in Disney theme parks, but many choose not to do so. Indeed, some fans design their own original cards (Baker 2016). Likewise, some fans purchase interactive wands at WWoHP, but not every fan does. Corporate creation and control of theme parks intersects with and complicates fan tourism. After all, the design of the theme park itself defines which spaces, experiences, and practices are more valued. Fans can buy sweaters and scarves in House colors in multiple shops, including Quality Quidditch Supplies and Madame Malkin's Robes for All Occasions clothing store. However, if fan knitters want to buy yarn in House colors or Harry Potter–themed knitting patterns to create their own sweaters, scarves, or other items, the Spindlewarps storefront is only a facade to display a recreation of Molly Weasley's Self-Knitting Needles.

[4.3] Such stores and their merchandise offer additional examples of what Paul Booth summarizes as the "incongruous refocalizations of the affective work of fans, exemplifying and highlighting commercial aspects of the media text important to the fan" typical of "industry-created fan destinations" (2015, 101). Furthermore, "rides like Terminator at Universal Studios, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Star Tours at Disney…allow for fan play within predetermined boundaries. Theme parks like Harry Potter's Wizarding World offer fans sanctioned spaces for imaginative exploration of the cult media world" (2015, 104). Fans can go to WWoHP instead of finding or creating their own environments, and buy licensed merchandise instead of knitting or otherwise making their own. However, finding or creating fan tourist sites often relies upon geographic proximity or else financial resources sufficient to pay for a trip cross-country or overseas, whether to WWoHP or London.

[4.4] Fans are more than capable of finding or creating their own sites for affective play. For example, fans interacted with a particular wall in the King's Cross Station in London in the everyday world as if it were the fictional Platform 9¾ resulting in a plaque marking that spot. Eventually a new sign and a luggage cart partially embedded in the wall directed fans to a new location, where Warner Bros. now offers formalized and corporatized versions of those original fan interactions. Official attendants sell photo opportunities with a selection of props and assistance with defined action poses. There also is a shop nearby selling licensed merchandise, officially designated as "The Harry Potter Shop at Platform 9¾" and commercializing the space even further. When media producers create destinations for fans, they "are poaching this type of affective play" (Booth 2015, 22) and "both enable and constrain fan audiences" (2015, 23). Of course, not every fan joins the long lines for the official photo opportunities. Fans still perform their own activities. They also claim some of the corporatized space for their own, as with the addition of a shrine after the death of Severus Snape actor Alan Rickman. Fan relationships with corporate sanctioned spaces are more complex than simple binaries of active or passive. Tourists can visit King's Cross Station in the everyday world, to interact with either the official corporate Platform 9¾, or to find their own version of that location and create their own experiences with it.

[4.5] Meanwhile, WWoHP offers versions of London landmarks such as King's Cross Station as filtered through the story world. In the line for the Hogwarts Express, visitors see people ahead of them walk straight through a brick wall at Platform 9¾. When they turn a corner and see how it's done, they then pass through that same wall themselves for their own enjoyment and for the amusement of others behind them. Visitors become, and are encouraged to become, by the theme park's own design, active participants in the attraction, in contrast to earlier models of theme park design that misperceived visitors as passive viewers of spectacles. Once on the Hogwarts Express ride, visitors' official role could be oversimplified as sitting passively and watching the sights. Yet dialogue here and elsewhere still addresses "you" directly, and refers to visitors as either Muggles or witches and wizards within the story world, encouraging immersion and active performances. Visitors can cast themselves as students or alumni traveling to or from Hogwarts, with their own adventures running parallel to or intersecting with narrative fragments glimpsed and overheard through windows and doors on the Hogwarts Express ride. These and other interactions with WWoHP attractions are both prompted and enabled by the corporations that create and control the theme park.

[4.6] However, corporations can neither predict nor control how everyone responds to every aspect of a theme park. Theme parks and other interfaces have multiple meanings to different visitors, or even within individual visitors. During my own trip to WWoHP, I insisted on photographs of myself standing next to one of the lampposts, much to the bemusement of my friends, since the lampposts were neither important nor prominent in any of the films. I had to explain that these were recreations of lampposts that line the river Thames opposite the Houses of Parliament. Their sculptures of stylized dolphins had captured my interest when I visited London as a teenager, so seeing them appealed to me as an Anglophile and brought back a wave of nostalgia from adolescence, as well as memories of spotting the lampposts in multiple films and television episodes since then. Recognizing familiar landmarks added to the verisimilitude of those media texts. Recreations of those lampposts in WWoHP's version of London also made it seem more believable to me, aiding both suspension of disbelief and immersion.

[4.7] On a related note, one fan notes that fan tourism, "with its blurring of borders…actually makes the film feel more real. After seeing that many of the locations in the movie are firmly anchored in reality, the locations are that much more believable" (Brooker 2006, 28). Walking through physical recreations of sets from the film franchise makes those fictional locations seem and feel more real. After fans walk down Diagon Alley in WWoHP, viewing Diagon Alley on a screen or reading about it in a book enables fans to revisit their memories of their own experiences and physical sensations within that "real" physical location, and thus make the fictional versions seem more believable.

5. Fan tourism to the wizarding (story) world, or I went to Hogwarts today!

[5.1] Related to immersion, fan tourism involves "multiple mapping," in which fan tourism sites "evoke other imaginary maps that have to be held in a double, triple, multiple vision alongside the real" (Brooker 2007, 430). WWoHP's Hogsmeade features snow-covered roofs, but even in early December, Orlando's bright sun and warm weather requires a related form of multiple vision: substituting cold for warmth, and snow-covered streets instead of hot pavement. Fans imagine and remember Diagon Alley filled with eccentrically garbed wizards and witches instead of throngs of tourists in T-shirts and shorts. Fan tourism uses human imagination to superimpose a story world onto our everyday world. Material interfaces enable fans to interact with and immerse themselves in story worlds, and fans actively participate in the process via such multiple mapping.

[5.2] Like fan tourism, theme parks enable fans to travel to the story world and back again to the everyday world. Rides offer "the sense that we can pass through and immerse ourselves in that experience—but also pass back, play at playing along" (Telotte 2011, 175), similar to the permeable boundary of cult geography Hills describes (2002, 146). Visitors enjoy playing at being Muggles or wizards, versions of themselves existing in a story world accessed via the material interface of a theme park and its attractions, but there is always that self-awareness of playing along. Visitors are not fooled. They return a knowing wink or nod. The crowds shopping for souvenirs slip through that permeable boundary to become the crowds in Diagon Alley shopping for magical supplies. There is an element of playfulness and an attitude of make-believe, even as WWoHP uses fans' imaginative practices as a framing device in an attempt to encourage consumption. Fans choose to suspend disbelief in order to immerse physically as well as mentally in beloved story worlds. The concrete material interfaces of theme parks provide permeable boundaries that allow interaction with and immersion in fictional story worlds.

[5.3] WWoHP and other attractions at Universal Orlando facilitate such immersion, with attendants in shops and queues dressing, speaking, and acting in ways consistent with each story world throughout the entire theme park. Line attendants for the Shrek ride wear pseudo-medieval film-peasant garb, and knowingly include a few "thee's" and "ye's" and other medieval vocabulary touches to their scripted interactions with visitors. Whether for Shrek, Minions, or any other themed area, employees remain in character. Fans choose to accept some elements, such as the scenic design of building facades or the presence of specific shops or the spells triggered by interactive wands, as interfaces to facilitate immersion in a beloved story world, despite the obvious fact that such magic doesn't exist in our everyday world. Fan tourists choose to willingly suspend disbelief and play along. Sometimes they board rides. Sometimes they buy souvenirs. Mostly they actively explore and interact with WWoHP's material environments and items. Fan studies offers understanding of fans and theme park visitors as far more than supposedly passive viewers of spectacles and consumers of merchandise.

[5.4] Fans interact with tangible recreations of familiar settings and props, creating their own original narratives in which they enter the wizarding world. Decades ago, Walt Disney "made the invisible and abstract concrete, in a form that can be experienced directly. Disneyland made the popular imagination visible" (King 2011, 225). Theme parks continue to offer concrete physicalizations of fiction: film or television images or written descriptions of buildings, clothing, food, drink, costumes, and other aspects of various story worlds. They offer material interfaces into imaginary story worlds. Interfaces offer immersive experiences in physical versions of story worlds. The concepts of interfaces and immersion could be applied to further fan studies examinations of other physical and material fan practices, such as cosplay, tabletop and live-action role-playing games, and Quidditch tournaments.

[5.5] In conclusion, theme parks function as material interfaces for visitors to immerse themselves within multisensory physical versions of story worlds. Such immersive performances require active engagement as performers, in contrast to conventional visual or written narratives, in which authors control plots, or directors and actors control images on screen, and viewers vicariously experience those offerings (Lancaster 2001, 32–33). Material interfaces enable visitors to become characters within new narratives. Universal Orlando's Wizarding World of Harry Potter and other theme parks continue this tradition. Countering misperceptions of visitors as supposedly passive viewers of visible spectacles and consumers of merchandise created and controlled by corporations, using fan studies as a theoretical framework illustrates how theme parks offer interactive, participatory, immersive experiences.