1. Introduction

[1.1] Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold (note 1) hoped to spark a revolution. In the month leading up to their massacre at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, that left 12 students and one teacher dead, both of the shooters documented their ideas, feelings, and motives intended for a worldwide audience in a series of home videos that would later become known as "The Basement Tapes." The two boys understood the media's insatiable thirst for tragedies, and they anticipated their posthumous stardom in a video filmed in mid-March 1999: "'Directors will be fighting over this story,' Dylan gushed. They pondered whom they should trust with their material: Steven Spielberg or Quentin Tarantino?" (quoted in Cullen 2009, 329). "Dylan adds, 'I know we're gonna have followers because we're so fucking God-like'" (quoted in Langman 2009, 58).

[1.2] While there would be no blockbuster Hollywood movie chronicling the boys' rampage, Eric and Dylan did have followers. Their iconic stardom with copycat shooters is undeniable: 17 school shootings have been directly connected to the Columbine massacre as well as 37 planned or attempted shootings, resulting in a total of 66 deaths and 49 wounded (Thomas et al. 2014). But to confine Eric and Dylan's appeal to only subsequent school shooters would critically undermine the importance of their lasting influence. The legacy of these two boys persists not just with shooters but also in active online communities. Their legacy persists with their fans.

[1.3] Although their massacre "pierced the soul of America," in the words of then-president Bill Clinton (1999), Eric and Dylan have indeed developed active online fandoms. Users on social networking sites such as Facebook, DeviantArt, and especially Tumblr post public comments and fan-created texts (e.g., sketches, videos, and blogs) in honor of the Columbine shooters while often fending off remarks from the general public criticizing their fandom. YouTube comments on tribute videos to Eric and Dylan have implored admirers to seek help, and other users have questioned the sanity or mental health of the fans openly professing their atypical interests. It is also common for blogs and Web sites dedicated to these Columbine shooters to have a disclaimer stating that the user does not condone the massacre but merely expresses an interest in the two boys. Despite this resistance, Columbine fans are active in such online communities as "I'm Obsessed with Eric Harris" (Blogspot), "Columbine High School Massacre" (Facebook page), and in arguably the most visible of these fandoms, "Columbiners" on Tumblr.

[1.4] A 2004 article by the Australian news outlet The Age attempted to provide insight into the "disturbing cult" that is Columbine fans ("Cult of Columbine"), but it only succeeded in conveying the common perception that these fans are unpopular, disturbed, and inevitably murderous individuals—just like the idols of their fandom. The specific usage of the term cult rather than referring to it as a fandom immediately denigrates this community. Furthermore, the author contrasts Eric and Dylan's followers with those of Columbine student Cassie Bernall, whose narrative as a heroic martyr for proclaiming her faith in God moments before her execution earned her comparisons to Christian saints as well as praise from a famous Baptist preacher as "the greatest Christian of the 20th century" ("Cult of Columbine" 2004). Despite the fact that Cassie's story was later debunked when surviving students correctly identified Columbine survivor Valeen Schnurr as the student who defended her faith, the author's choice to contrast these followers to Eric and Dylan's fans further supports the claim that the fandom is stigmatized.

[1.5] There are plentiful academic analyses covering many aspects of fandom, but when examining fans of particularly challenging subjects like the Columbine shooters it appears that it is all too easy to play into the negative stereotypes of obsessive fannish behavior as disconnected from reality. If the first wave of fandom studies could be described as "fandom is beautiful," as Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington (2007, 3) remarked, then this study focuses on the opposite—this study explores the darkness of fandom. Fan studies have covered the various types of fans (e.g., the antifans and nonfans described by Gray 2003) as well as their myriad interests centered on almost any mainstream and even cult text, but less research has been dedicated to the fans of these challenging and even polarizing figures. To address this gap in literature, I examine the Columbine fandom to understand the dominant motives that these fans appear to have for engaging with and around such controversial figures and then conclude by exploring how the Columbine fandom might help us to more broadly reflect on our concept of fandom. I hypothesize that despite the stigma and frequent denigration, the Columbine fandom is comparable to other more conventional fandoms in that it is also a lively and diverse community rich with socially relevant insights that can benefit not just our understanding of Western culture but specifically of the field of fan studies as well.

[1.6] No fans were directly interviewed for this study, but their comments, posts, and fan-produced texts are publicly available via multiple social networking sites. These contents were analyzed for what they appear to reveal about why Columbine fans partake in this particular fandom, although it is acknowledged that this fannish behavior may sometimes stem more from troll behavior and attention seeking rather than from genuine interest. The participatory culture of each specific platform was also taken into account when examining the content. For example, while Columbine fans on Tumblr may use numerous methods of expressing their interests such as comments, images, GIFs, audio clips, and videos, these same fans on YouTube are largely restricted to comments and videos. While many social networks and fan communities were analyzed, the three Web sites that provided the most discussed Columbine fan material in this study were Facebook, Tumblr, and DeviantArt—the last of which served as a plentiful source for fan-produced texts in honor of Eric and Dylan. It is also important to note that the 16th anniversary of Eric and Dylan's massacre occurred during the time period of data collection, in which there was an expected spike in fan texts and activity.

[1.7] Last, it should be stated that the intent of this study is not specifically to defend fans of the Columbine shooters but rather to expand and challenge the object of focus when studying fandom. In praising the potential of a more participatory culture to lead to critical engagement about key issues and imbalances in our culture, has that caused us to be selective in the fandoms that we study and the cases that we explore? Chen (2012) studies the fandom surrounding James Holmes, the Aurora movie theater shooter who killed 12 people. To understand this question, we must also take a similar journey into the dark heart of Internet fandom.

2. Holmies and a history of fandom

[2.1] Chen's (2012) analysis of James Holmes's online fans, or Holmies as they refer to themselves, followed an article by Buzzfeed's Ryan Broderick (2012) in which he unearthed several fan texts dedicated to Holmes. Broderick presents fan art such as drawings and sketches dedicated to Holmes as well as Tumblr users' photos of themselves wearing plaid shirts in honor of the apparel that Holmes was allegedly wearing during his arrest. Broderick also notes that Holmies have created an inside joke based on a video of a teenage James Holmes discussing Slurpees, while other fans post information and questions regarding how to write to the movie theater shooter in prison. However, Broderick's article does not challenge the stigma associated with this type of fandom and instead simply refers to the community of Holmies as "horrible" and the fandom as a "dark world."

[2.2] Chen's (2012) analysis probes more deeply into the community by drawing comparisons between more accepted fandoms (e.g., Trekkies and Twihards) and Holmies. Speaking of all fandoms, including Holmies, he notes that "they adopt the symbols of their fixation and come up with slang, they create memes based on tiny details of a character and construct elaborate fantasy worlds and fan art." Chen appropriately cites the Internet as an important and enabling factor in such fandoms, and he argues that Holmies are an example of fandoms as their own subculture. His analysis remains focused on this "explosion of internet fandom" and how the field has evolved—or rather, devolved—as a result of the growth of media technologies. While Chen's study does provide useful theory for the expansion of such a controversial fandom, a complementary study would pay specific attention to the fans and would explore the deeper societal meanings within and generated by the activity of engaged fandoms for such challenging public figures.

[2.3] The field of fan studies originated in defending fandoms and arguing for the social relevance of these communities. As briefly discussed earlier, Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington (2007) examined the three waves of fandom and began their study with the first wave when academics first deemed fans and their activities worthy of critical study. Initial fans were commonly dismissed as Others, yet in-depth analyses later revealed that they could be a part of rich and lively communities for fans to openly express and engage in their interests while even critiquing the social norms and practices that deemed their fandom as outsiders. Jenkins (1992) wrote that fans are dismissed as atypical of the common media audience because of their resistance and activity such as blurring boundaries of media norms and denying unsatisfactory series endings by rewriting or producing their own fan-made finales. Coppa (2006) also examined this initial recognition by mainstream culture in the late 1960s and noted how Star Trek, one of the most popular fandoms, was at first divisive within the science fiction community because it was dismissed as "science fiction for non-readers" (45). She argues that one of the contributing reasons why Star Trek and its fans struggled during this early stage was because it lacked legitimization (i.e., recognition) and noted that "Media fandom…clearly began its life in a very small pool" (44). Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington (2007) discuss the concept of "mainstream fandom" dependent on "public recognition and evaluation" that legitimizes the practices of being a fan (4). With this legitimization, devotion to a band or a singer or a public crush on a celebrity has always been considered acceptable (Coppa 2006) because these fandoms have come into the social consciousness and been acknowledged by mainstream culture.

[2.4] The second wave of fandom highlighted the replication of social and cultural hierarchies within fan subcultures and saw these fan practices as "a reflection and further manifestation of our social, cultural, and economic capital" (Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 2007, 6). In this second wave, Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington argue that fans are seen not as a counterforce to existing social hierarchies and structures but rather the opposite: they are seen as "agents of maintaining social and cultural systems of classification and thus existing hierarchies" (6). Jenkins (1992) supports this notion that fan practices can provide relevant social and cultural insights. For example, while on the surface slash fiction may seem nothing more than female fans satisfying their fantasies with male characters of popular series, Jenkins argues that these slash stories comment on the way in which our culture negotiates a complex transition on how it thinks about male sexuality (e.g., Kirk and Spock slash fan fiction may have the two popular male characters engaged in sexual acts).

[2.5] The third wave of fandom departed from yet also built upon the conceptual heritages of the first two waves and aimed to capture the variety of fans and their interests. Gray (2003) calls for a reinvigoration of media and cultural studies of televisual audiences by arguing for the inclusion of different types of fans, specifically regular "fans, anti-fans, and non-fans" (64) who view texts without any intense involvement. Bird (2011) adds the inclusion of the "non-produser" fan, or the fan who isn't actively producing and engaged in fan activities yet still remains at least somewhat dedicated to a text or public figure (502). This parallels Gray's concept of the nonfan in that they may not be as heavily involved as other more devoted fans and may only read texts at a paratextual level (i.e., through promotional materials). Both Gray's and Bird's studies contributed to the third wave of fandom by arguing for the inclusion of often-overlooked types of fans, although these types remain a part of more conventional and socially accepted fandoms such as The Simpsons (1989–) and Bollywood films.

[2.6] Despite the three waves of fandom covering a significant amount of academic ground and revealing the types of fans and their myriad interests, few studies have expanded their focus into challenging fandoms such as those of Columbine shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. As a result, it seems that this and other dark fandoms remain rooted in the first wave where these fans are dismissed as Others and their communities lack legitimization and acceptance by society. Though Columbine fans and similar communities have at times permeated mainstream culture and been the subject of analyses, they are largely framed to play into negative stereotypes of these fans as "excluded, bullied, murderous, and lost" ("Cult of Columbine" 2004). It appears that rather than investigating these communities for their potential social relevance and valuable insights into media research, most journalists have settled for continuing the stigma attached to these fans, and scholars have largely overlooked or altogether ignored the potential of these fandoms. To understand how these fandoms could be rich sources of knowledge that help us to more broadly reflect on our concept of fandom, the dominant motives of these fans must first be considered in order to understand why they appear to partake in such a frequently denigrated community as that devoted to Eric and Dylan. By understanding these motivations, it is possible to see fans of the Columbine shooters—and of other challenging public figures—not as reflections of the idols of their fandom but rather as part of rich, lively, and socially important communities.

3. Columbine as retribution: Fans identifying with Eric and Dylan

[3.1] Drucker and Cathcart (1994) stated that celebrities need to be a presence, to be the focus of media attention, and to be someone with whom the public can readily identify (268). Eric and Dylan meet the first two of these criteria, and they meet the third one—to be public figures who serve as points of identification—largely as a result of the media's framing of the two gunmen. During the days immediately following the tragedy, numerous Columbine students interviewed with local and national media stations and gave their insights into the shooters' daily lives at their high school. Many of these students were incorrect in their claims and, despite acknowledging almost no connection to Eric and Dylan, continued to report what they thought they knew about the shooters. Mistaken claims included that Eric and Dylan were goth students, that the two boys regularly practiced voodoo and witchcraft (Gibbs and Roche 1999), and that the two boys were gay (Cullen 1999). But an interview with Columbine junior Bree Pasquale in the moments after the massacre provided the most newsworthy narrative when she frantically informed reporters that Eric and Dylan had specifically targeted athletes. Dave Cullen, a leading investigative journalist on Columbine, noted the effect of Pasquale's and other students' interviews: "The public believes Columbine was an act of retribution: a desperate reprisal for unspeakable jock-abuse" (2009, 151).

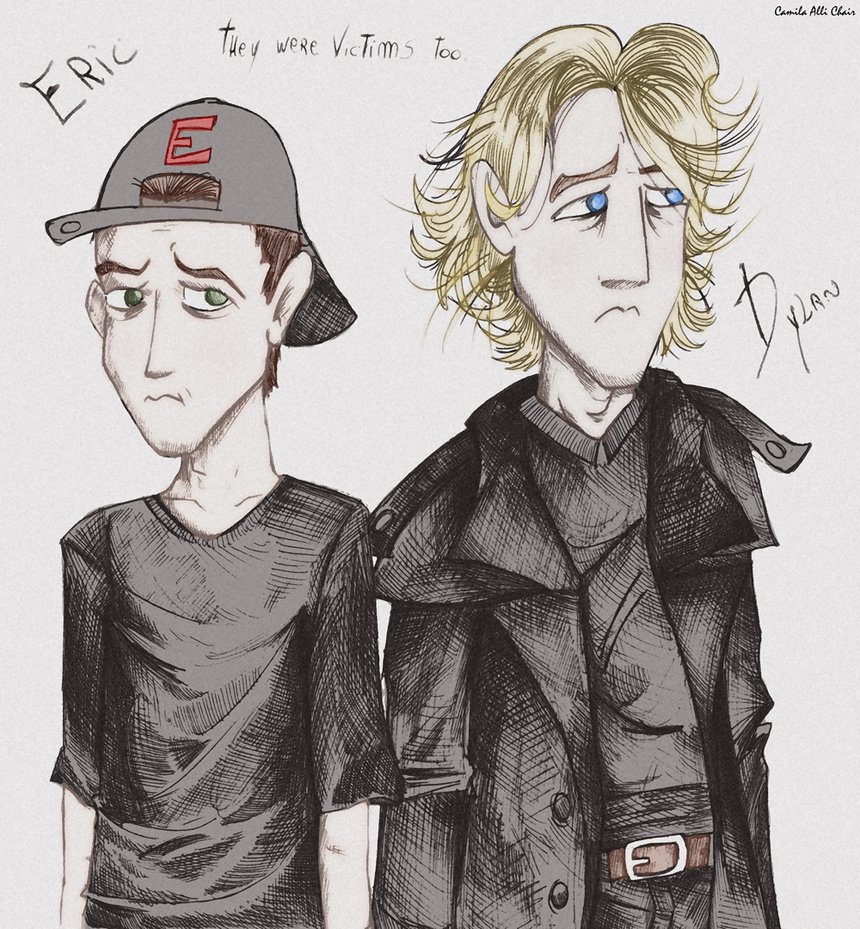

[3.2] This lasting public perception of Eric and Dylan's massacre as an act of retaliation against the cruel yet socially superior athletes appears to manifest within the Columbine fandom. This belief is most noticeable in the fan-created texts that reconceptualize Eric and Dylan as victims of the bullies, of the unhealthy social atmosphere at Columbine, or of society for enabling the athletes to torment with impunity. These texts are either entirely fan made using such creative methods as drawing, sketching, or painting. In other cases, fans poach, to borrow a term from Jenkins (1992), existing material of Eric and Dylan—most notably their yearbook photos and self-documented videos—and revise the content to fit their desired purpose (figures 1, 2, and 3).

Figure 1. A fan using the name Eric Harris as a Facebook pseudonym uses a photo of Eric Harris from the Columbine High School yearbook to reconceptualize Eric as a victim. "Society Killed the Teenager." (Eric Harris, Facebook fan page, April 2015) [View larger image.]

Figure 2. A fan's drawing of Eric and Dylan. "They were victims too." (Iguana-teteia, DeviantArt, November 2013) [View larger image.]

Figure 3. A fan's text in memory of Eric and Dylan using the gunmen's self-assigned nicknames Reb and Vodka, respectively. "Remember the real victims." (Eric Harris, Facebook fan page, June 2015) [View larger image.]

[3.3] In the years after the massacre, Eric's and Dylan's personal documents (e.g., journals, videos, and school papers) were gradually released to the public and provided valuable insight into the minds of the killers. Jeff Kass (2014), another leading Columbine journalist, wrote that Eric was "just like Dylan Klebold: sad, lonely, depressive. If Eric truly felt superior, it came from a sense of inferiority" (198). Kass cited one of Eric's journal entries from late 1998 as evidence:

[3.4] Everyone is always making fun of me because of how I look, how fucking weak I am…I have always hated how I looked, I make fun of people who look like me, sometimes without even thinking sometimes just because I want to rip on myself. That's where a lot of my hate grows from. The fact that I have practically no selfesteem, especially concerning girls and looks and such. (198)

[3.5] Eric and Dylan's framing as sad, inferior, and bullied outcasts is especially apparent within the Tumblr fan community known as Columbiners. In an interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), a self-identified Columbiner offered her insight as to why she believes two of her fellow fans planned to carry out a similar school shooting before they were stopped by local law enforcement. When asked to speculate why she, along with the rest of the active Columbiner fandom, identifies with Eric and Dylan, the young fan cited an understanding of the two boys and their problems: "A lot of people identify with the feelings of the shooters. So we kind of take comfort in it in a way, since a lot of us feel depressed and anxious, and they did too. So it's kind of nice since a lot of people don't necessarily have someone there who understands them and feels the same way as them" (quoted in Bambury 2015).

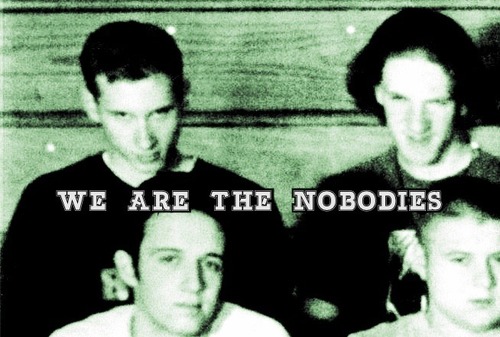

Figure 4. A Columbine class of '99 photo zoomed in on Eric and Dylan with the words, "We are the Nobodies." (truecrimejunkie77, Tumblr, May 2015) [View larger image.]

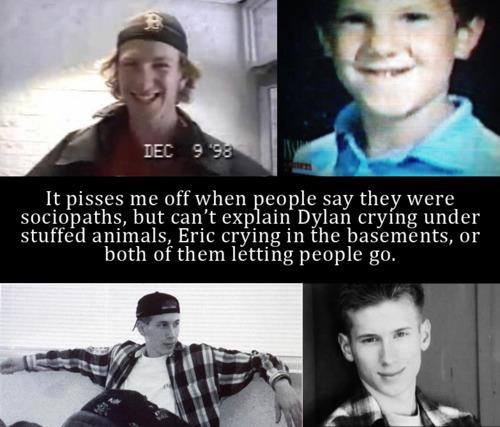

Figure 5. A fan defends the Columbine gunmen. (blueeyedtragedy1976, Tumblr, April 2015) [View larger image.]

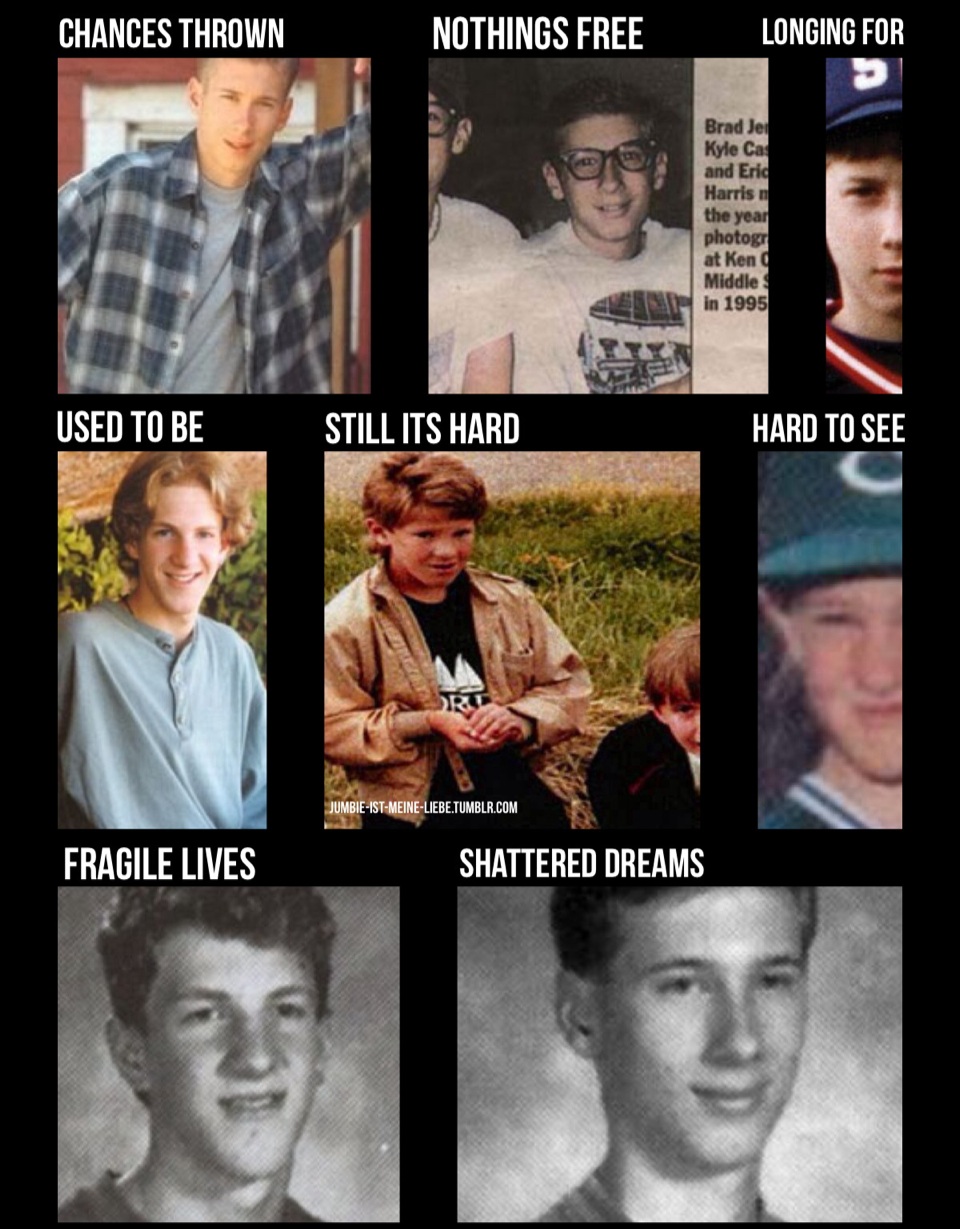

Figure 6. A fan uses lyrics from "The Kids Aren't Alright" (1999) by The Offspring with images of Eric and Dylan throughout their lives. (jumbie-ist-meine-liebe, Tumblr, May 2015) [View larger image.]

[3.6] On the basis of this claim and the provided fan texts (figures 4, 5, and 6), an argument could be made that Columbine fans not only identify with Eric and Dylan but that they also empathize with them, thus fitting into Kooistra's (1989) argument that real criminals can also serve a cathartic function for their audience. Columbine fans seem to express through their created or poached texts that they understand Eric and Dylan while the general public does not, such as in figure 5, where a fan refutes the claim that the two boys were sociopaths by citing their emotional pain ("Dylan crying under stuffed animals, Eric crying in the basement") as well as their mercy ("both of them letting people go" in reference to Eric telling his friend Brooks Brown to "go home" moments before the massacre, and to both shooters permitting student John Savage to leave the library during their execution of 10 students [Brown and Merritt 2002]). But while these fans may claim an esoteric knowledge regarding Eric and Dylan, they may also be playing into a wider cultural practice that dates back to such notable examples as the rise of Charles Manson in the 1970s. These fans may be specific examples of Western culture's interest in killers that enables such figures as Eric and Dylan to polarize the public and dominate media reports for months and in some cases even years after their committed atrocities.

4. Death, wounds, and the lure of the forbidden

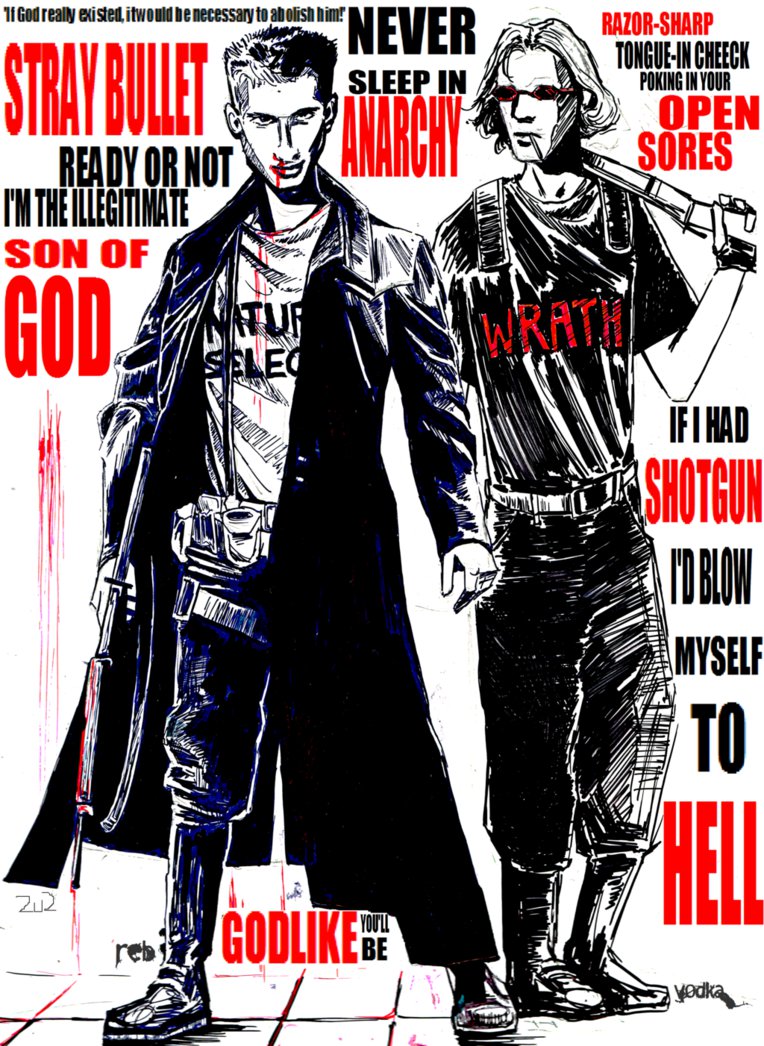

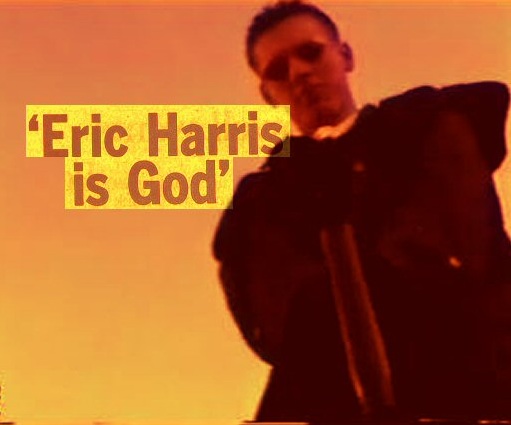

[4.1] In order to challenge and ideally expand the focus of fan studies, Eric and Dylan—in addition to other murderers in Western society who are the subjects of fandoms—must be viewed within the contemporary public sphere in which killers are arguably a defining feature of American popular culture and have achieved a high level of visibility as celebrities. Dave Cullen (2013) addressed the specific stardom of school shooters in an article for Buzzfeed in which he challenged news outlets to "Stop Naming Mass Shooters," to quote from the article's title, and providing them with the glorification of leading news stories. Schmid (2006) also discussed the media's tabloidization and sensationalization of crime that contribute to the killer's appeal, and he cited two additional reasons for their popularity: killers tap into what he terms the "market for death" (i.e., they provide the dual needs for representations of death and of celebrities), and growing media technologies create and disseminate their fame (13–20). This last point is especially important to note when examining how shooters like Eric and Dylan are disseminated as figures within fan communities. In the years prior to the ubiquity and accessibility of the Internet, fans of dark public figures were limited in their resources to express their interests. Now there are numerous online outlets and social networks for these fans to meet other like-minded people and openly declare their interests that fall within the market of death. Although less empirically evident than fans stating that they identify with the Columbine shooters, multiple fan texts do appear to reflect the media's sensationalization of crime as these texts frame the two boys in glorified positions (figures 7 and 8) and, in some instances, as superior beings (figures 9 and 10).

Figure 7. A fan's rendering of Eric and Dylan on the day of the massacre. (jellyfishly, DeviantArt, August 2010) [View larger image.]

Figure 8. The Columbine gunmen glorified by the use of terms like "son of god" and "godlike." Notice Eric's bloody nose in this image, which actually happened during the massacre when his shotgun recoiled in his face. This is one of many examples of the meticulous attention paid by fans when creating their texts. (SomebodySomeone95, DeviantArt, July 2014) [View larger image.]

Figure 9. A still of Eric in one of his student videos ("Hitmen for Hire") edited by a fan. "Eric Harris is God." (voDKasvengeance, DeviantArt, August 2005) [View larger image.]

Figure 10. A memorial text dedicated to Eric Harris using many images of the shooter, including his suicide in the Columbine library (background) and the word "godlike." (Eric Harris, Facebook fan page, February 2015) [View larger image.]

[4.2] It should be noted that Eric and Dylan often referred to themselves as gods in their personal documents, but these fan texts incorporating the shooters' blasphemous claims still provide valuable insight into the fandom. Perhaps the fans who created these texts labeled Eric a god as a perverse way of honoring his legacy, or their admiration for him may be so extreme that they genuinely do consider him to be a higher being. This could also relate to another example of an extreme investment in the Columbine fandom: a physical attraction to either one or both of the gunmen. Gael Sweeney's (1994) description of distinctive features explaining why television teen idols are appealing to women is applicable to Eric and Dylan as well: they are often at odds with the law, they do not fit into the dominant male ideology, and they are male but not phallically male (i.e., they are masculine, but not so masculine as to intimidate their female admirers). These traits, combined with the argued appeal of killers in Western culture, manifest within the Columbine fandom as users post comments and images expressing their attraction to the shooters (figures 11, 12, and 13).

Figure 11. A fan expresses physical attraction to Columbine gunman Eric Harris. (Eric Harris, Facebook fan page, June 2015) [View larger image.]

Figure 12. A Columbiner on Tumblr edited Eric and Dylan's high school photos with flowers, hearts, and compliments. (socio-apathy, Tumblr, April 2015) [View larger image.]

Figure 13. Another text declares a fan's attraction. Data collection revealed that Eric in particular is subject to this type of fan activity more than his partner in the shooting spree. (Eric Harris, Facebook fan page, May 2015) [View larger image.]

[4.3] The glorification of Eric and Dylan and fans' claims of their physical attraction to one or both of the shooters provide an intersection between fandom and a fascination with death. Seltzer (1998), in a complementary argument to Schmid's (2006) concept of the market of death, claims that this intersection occurs because the American public collectively gathers around shock, trauma, and the wound because of a fascination with scenes of violence in what Seltzer calls a "wound culture" (21). Seltzer cites the everyday occurrence of a car accident and how it's common for drivers and bystanders to convene around (or at least gaze at) the accident to satiate their curiosity. Evidence of this intersection may be most evident in fan texts that recreate or reinterpret Eric's and Dylan's suicides in the Columbine library 49 minutes after they began their massacre. Although the actual crime scene photo of the aftermath of their deaths is extremely graphic, it is also easily accessible via a quick online search—so any Columbine fans curious as to how the idols of their fandom met their end can quickly find the image. Fan texts of this photo often add an artistic spin by contrasting colors (most notably white, black, and red) as well as playing with positioning and juxtaposition (figures 14, 15, and 16).

Figure 14. In an accurate drawing of the actual crime scene photo from Eric and Dylan's massacre, a fan draws the two gunmen after their deaths in the library. (LittleSkrillexKid, DeviantArt, September 2011) [View larger image.]

Figure 15. A fan either reimagines the Columbine gunmen's deaths or plays with their positioning by placing their heads side by side, likely for dramatic effect. (Artist unknown, DeviantArt) [View larger image.]

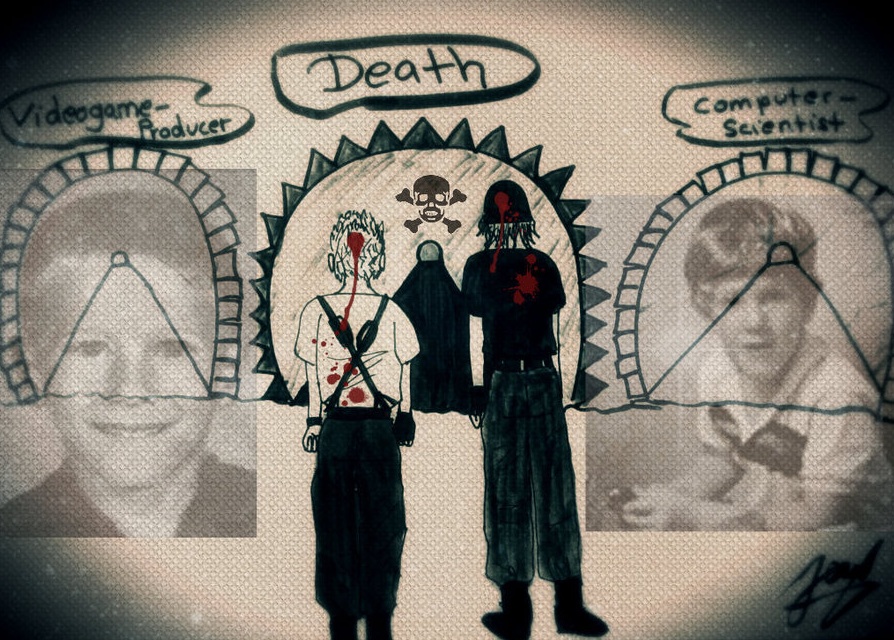

Figure 16. A fan juxtaposes the deaths of Eric and Dylan with photos of the gunmen as young children. It appears that this fan also labeled which career each of the gunmen may have pursued: Video game producer for Eric and computer scientist for Dylan. (Artist unknown, DeviantArt) [View larger image.]

[4.4] Whether or not killers like Eric and Dylan have a mass appeal in Western culture is becoming increasingly difficult to argue against as they continue to take center stage in the news and entertainment media, and recent reports covering similar tragedies seem to have ignored Cullen's (2013) challenge to cease the glorification of the perpetrators. Consequently, the aforementioned market for death and wound culture, as well as the intersection between fandom and violence, do appear to manifest in some of the fan texts within the Columbine community. Thus, part of the appeal of partaking in a Columbine fandom may stem from exploiting this lure of the forbidden and tapping into our curiosity for scenes (and people) of violence. Fans who claim that killers are godlike or attractive, and especially fans who are interested in images of violence such as Eric's and Dylan's suicides, are often denigrated and labeled as social outcasts. Such iconoclastic interests frequently attract attention, and although it's often negative attention, these fans can almost certainly expect a reaction from the public. While this lure of the forbidden and identification with the killers may constitute two of what appear to be the most dominant motives for Columbine fans, there is a third and equally important potential motive that must be considered: that these fans are trolling.

5. Columbine fans trolling for the spotlight

[5.1] On March 1, 2012, Tom Mauser—the father of slain Columbine student Daniel Mauser—uploaded a video to YouTube titled "Columbine dad responds to H&K admirers."

[5.2] I'm posting this message in response to the dozens of Youtube messages I've received over the past few months from people claiming to be admirers of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold…There are two primary kinds of people who have responded: internet trolls, and Harris and Klebold sympathizers. First, internet trolls are basically people who are thoughtless, compassionless people who have nothing better to do with their time than to troll the internet and find ways to disturb people—they poke them in the eye with a stick. They especially do this on memorial websites like the one I have for my son, they try to elicit a reaction of outrage or fear. They are basically trying to get attention for themselves, they try to exert, feel power over people, they can do this impersonally on the internet, and they can do it without having to identify themselves. (Mauser 2012)

[5.3] While this example of fans going out of their way to upset the father of a Columbine massacre victim may be a more insidious instance of trolling—that is, when online instigators post abusive comments and images for attention—it is still a worthy point of entry into a potential reason for fannish engagement within the Columbine fandom. The concerns about trolling expressed in Mauser's (2012) video echo Whitney Phillips's (2011) analysis of trolling specifically within Facebook memorial groups and fan pages, which she labels "RIP trolling." Phillips argues that there is a "parasitic relationship between memorial trolls, Facebook's social networking platform and mainstream media outlets" and that these trolls present a "pointed critique of a tragedy-obsessed global media." Whether or not these trolls do critique the global media, they are evident in Columbine fan communities and, as Tom Mauser discussed, have also infiltrated numerous memorial Web sites.

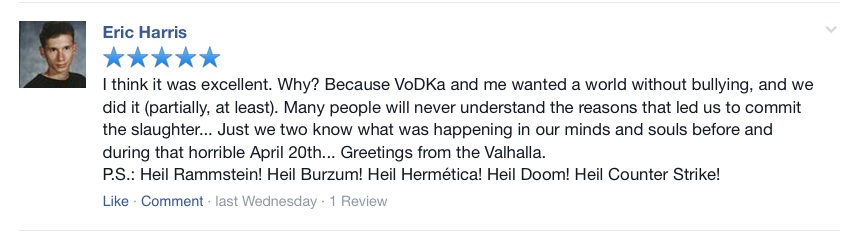

[5.4] In one of the most ambiguous Columbine communities, the Facebook page Columbine High School Massacre appears to draw both sympathizers and fans (i.e., trolls) alike. Two of Facebook's features complicate an analysis of the purpose of users on this page: the "like" button and the ability to rate the page with 0 to 5 stars. At the time of writing, this page has over 8,500 likes from Facebook users around the world, although what exactly these users like certainly varies. While some may have been trolling for attention, others may have liked the page out of either a genuine interest in the case or as an act of support for those affected by the tragedy. The ability to rate the Columbine High School Massacre Facebook page further complicates the intent of this community, though the current rating of 4.3 out of 5 stars (on the basis of 232 ratings) arguably conveys a clearer, more sinister message than does the number of likes. The comments section, however, provides more clarity. Numerous users post messages of remembrance ("R.I.P. to the innocent people who were killed"), some post messages of hatred towards Eric and Dylan ("Those two were monsters"), and one user even claims that his cousin was killed in the massacre. Trolls, expectedly, also figure prominently into this section as they comment in numerous incendiary messages on the page, even posing as one of the killers (figure 17):

[5.5] By far the best event in history. (Dustin Vanharn, March 2014)

Good for a giggle. (Mick Halcrow, October 2013)

Amazing, I absolutely adore it. 5/5 would watch again (Benas Maskaliovas, May 2015)

10/10 would hug Eric and Dylan. Best Massacre in the world. (Vincent Olivieri, April 2015)

The chemistry between the shooters and the victims' faces were amazing. (Pierce Thomas Soulsby, March 2014)

Figure 17. A screenshot from the Columbine High School Facebook page of a fan trolling by using Eric Harris's junior yearbook photo and name to assume the identity of the gunman (note 2). (May 2015) [View larger image.]

[5.6] These trolls, similar to those who have harassed Tom Mauser, meet the description of Phillips's RIP trolls who blatantly seek to disturb online communities and provoke heated reactions from other users. But not all trolls appear as transparent with their motives, and some Columbine fans may even be partaking in the fandom in order to be a part of something that in and of itself often incites reactions from the public. As Chen (2012) noted in his analysis of James Holmes fans, "Nothing brings a fandom together better than their weird passion being mocked by outsiders. Now that fandom is largely about the act of being a fan, this mockery can be the very thing the fandom is after." Like the Holmies fan community on Tumblr, Columbiners also face ostracism and mockery from others who don't understand their different interests—a theme that ironically parallels Eric and Dylan's lives as they too were frequently ridiculed. Within this community, it is not a rare occurrence for outside users to police the Columbiners and insult their fandom:

[5.7] Dear self-titled "Columbiners," You're disgusting wastes of oxygen. (jangysprangus, Tumblr, April 2015)

You guys are all huge fucking weirdos. (captainbeefheartandhismagicband, Tumblr, April 2015)

Columbiners need to chill they're scaring outsiders lol. (sick-boy, Tumblr, March 2015)

I wonder how many of you columbiners/fangirls/boys would actually lose your mind if you went to jail. You're softer than baby shit. (panzerterror, Tumblr, April 2015)

Me: *finds out about the columbiners tag and goes through it*…When will the aliens come and abduct me from this horrible planet? (badasskujo, Tumblr, April 2015)

[5.8] Columbiners are often quick to defend their interests in response to these criticisms, thus inadvertently supporting Chen's (2012) point that mockery may be a dominant and unifying motive in this type of fandom:

[5.9] Why are Columbiners demonized so hard????? We're all kind and supportive of each other but we get so much hate I don't understand?????????? (twistedlosers, Tumblr, April 2015)

Maybe my moral compass has disappeared or something but why the fuck do you need a reason to be interested in true crime or more specifically Columbine? (socio-apathy, Tumblr, May 2015)

I don't understand why people think that all columbiners are psychopaths. 9 out of 10 times, the person you're sending hate to is a completely normal teenager! Most columbiners are interested in the story and don't condone what Dylan and Eric have done. Even if they do, that still doesn't make the person a fucking murderer. We are normal people, interested in something that should, and I hope one day will be considered normal. We have our interests and you have yours, ours is just a little different. So please, don't send hate just because we have our differences. (darkenwonders, Tumblr, March 2015)

[5.10] Columbiners and most other comparable fan communities are ostensibly private but in actuality more closely identify as public social spaces. That is, these fandoms are mostly open to the public and require minimal effort to become members, such as joining a group or clicking the "like" button. As a result, it's difficult to note which online users are genuinely fans and which others are merely fans partaking in something that will inevitably garner attention (albeit negative attention). That people who greatly dislike Columbine fans can easily infiltrate these communities with their comments of mockery and ridicule attests to the ease and accessibility of such fandoms. But that isn't to discredit those who are interested in Eric and Dylan, and that especially isn't meant to discredit those who truly do consider themselves fans of the gunmen. It's simply to note that with constantly rising media technologies that enable anonymous and pseudonymous behavior and with the simplicity of partaking in such controversial fandoms, it's becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish among trolls, genuine fans, and everyone in between.

6. Conclusion and takeaways for the field of fandom

[6.1] The 16th anniversary of Eric and Dylan's massacre at Columbine High School occurred during the period of data collection for this study. A quick Google search on this day using the sole term Columbine returned many results, most of which focused on the anniversary and provided fast facts for inquiring readers. One result in particular stood out: "Student in Spain Kills Teacher, Wounds Others, Possibly Inspired by Columbine" (2015). Although a police spokesman acknowledged that it's "too early to determine whether the incident…was an attempt to copycat the April 20, 1999, attack in Columbine," the fact that this notion is even entertained attests to Eric and Dylan's long-lasting—and apparently far-reaching—influence. But as argued in the beginning of this study, confining Eric and Dylan's appeal to only psychopaths and aspiring school shooters would critically undermine what they can teach us about Western culture and, more specifically, about the field of fandom. It is true that some of the more recent shooters—from Sandy Hook Elementary gunman Adam Lanza to Virginia Tech shooter Seung-Hui Cho—documented their admiration for Eric and Dylan and appeared to be fans of the two Columbine killers (Thomas et al. 2014), but they represent only one method of entry into the Columbine fandom. As this study has intended to prove, there are multiple methods of entry into such a complicated and challenging fandom as that of the Columbine shooters. Fans may appear to identify or even empathize with Eric and Dylan as social outcasts, or perhaps they are more drawn to the lure of the forbidden of joining such a provocative fandom. Or, and this is especially relevant considering the ubiquity and accessibility of technology, they might just be doing it for the attention—to incite reactions from the public and, as Tom Mauser (2012) said in his video, to "poke them in the eye with a stick."

[6.2] While these reasons appear to be three of the most prevalent motivations for joining the Columbine fandom, it is in no way an exhaustive list of all of the reasons. These are provided in an effort to challenge and expand the object of focus when studying fandom to include less conventional fan communities that arguably remain stuck in the first wave. Though fan studies has made great progress since science fiction and action-adventure shows such as Star Trek (1966–69) and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964–68) first permeated the cultural zeitgeist in the late 1960s, fandoms such as that of the Columbine shooters still lack acceptance and legitimization by society, and their fans appear to still largely be dismissed. Perhaps this is because the objects of such fandoms are particularly challenging and often play into negative stereotypes. The fandom of the Columbine shooters expectedly evokes extreme and derogatory images of fannish behavior that most often manifest in crime procedurals and news reports. Furthermore, this negative stereotype seems to be validated every time another Columbine happens (note 3); that is, such headlines as the student in Spain who was possibly inspired by Columbine to kill his teacher often validate the stigma and denigration associated with Eric and Dylan's fan community. As with the other initially dismissed fandoms during the first wave that were later proven to be rich and lively communities of social relevance, the Columbine fandom consists of diverse individuals united by their specific interest in Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold.

[6.3] This brings us to the bigger question: why does any of this matter? Specifically, why does this matter to the field of fan studies? The Columbine fandom, while one of many of its kind centered on dark public figures, is part of a larger trend of admiring controversial figures that continues to develop over time. While it's easy to argue against the morality of placing prisoners, murderers, and terrorists in the same public spotlight as more conventional celebrities, it is getting increasingly difficult to argue against the existence of their public appeal. Jeremy Meeks, who rose to fame as the Hot Convict when his mug shot went viral in June 2014, has over 306,000 likes between two Facebook fan pages, and Rolling Stone experienced a sales increase of 100 percent with their controversial July 2013 issue displaying Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev on its cover (Kavilanz 2013). But as former Columbine student Brooks Brown noted, the media "makes money by giving people what they want…it feeds on who we are and how we live" (Brown and Merritt 2002, 16). So if there was no demand for murderous public figures like Eric and Dylan, and if there was no audience to partake in a fandom dedicated to these shooters, then their images and influence would cease to permeate the public sphere. These figures do continue to dominate news reports and influence fans for years after their crimes, yet fan studies has largely overlooked the importance that these polemic figures can have to the field. To better understand this appeal as well as the field of fandom as a whole, studies must expand to include challenging and often denigrated fan communities such as that of the Columbine shooters. To better understand Internet fandom, the field of fan studies must be willing to journey deeper into the darkness.