1. Introduction: Access denied

[1.1] Fan edits are essentially alternative versions of feature films and television shows created by fans using desktop video editing software. Fan edits take many forms, often to refine or expand a narrative, to shift genres through aesthetic and structural changes, or even to create recombinant story lines using multiple films and television episodes, among other approaches. Fan editing practice has evolved much since the controversial reception of Star Wars Episode I.I: The Phantom Edit (2000), which was a seminal fan edit based on George Lucas's Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999). As I argued in a 2014 essay, "Fan Edits and the Legacy of The Phantom Edit," fan edits have frequently been misinterpreted as poorly executed reactionary works made by disgruntled fans. On the contrary, many fan edits are the products of talented people who creatively reinterpret existing media in the spirit of narrative and aesthetic experimentation.

[1.2] In that essay, I also explained how ethical and legal questions have stigmatized fan edits since the public breakthrough of The Phantom Edit (Wille 2014, ¶4.6). Fan editors maintain that their works are noncommercial, while communities like Fanedit.org (http://www.fanedit.org) and OriginalTrilogy.com (http://www.originaltrilogy.com) collectively stand against media piracy by forbidding the sale of their transformative works. These communities also mandate that prospective fan edit viewers should purchase legitimate copies of all films and television titles before downloading fan edits based on them. This legally untested strategy assumes that the creation and consumption of fan edits would be protected under the fair use provisions and first-sale doctrine codified in the US Copyright Act of 1976 (Wille 2014, ¶4.7).

[1.3] However, not all fan edits are easily accessible, and fan editors often struggle to find trustworthy means to distribute and store their works online. Despite ongoing efforts by the Organization for Transformative Works to maintain exemptions for transformative video projects under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, popular third party media storage and delivery services like YouTube (https://www.youtube.com), Vimeo (https://vimeo.com), and Dailymotion (https://www.dailymotion.com) frequently purge transformative videos on grounds of copyright infringement (Fraimow 2014, ¶2.6). Thus, to avoid such takedowns, fan editors typically rely on less regulated distribution channels such as file locker Web sites, newsgroups, and torrents, but these methods require the use of specialized software that may deter some casual viewers: "Flat-out pirates are more open with distributing their stuff than these fan-editors. Like 'Here's a page all about this thing that you have to solve the fucking da Vinci code to download'" (Bkwordguy 2014).

[1.4] Contemporary procedures for finding, downloading, and preparing fan edits for viewing are understandably daunting for uninitiated computer users. Fan edits are generally feature-length creations that account for several gigabytes of data on disk. Large file sizes often mean that the most viable online distribution channels for fan edits are the same as those commonly used to share pirated digital copies of feature films, television episodes, and software. Prospective viewers must wager their interest in procuring fan edits against any risks of using these legally contested online services.

[1.5] Furthermore, the mercurial nature of file lockers and BitTorrent indexers can make access to fan edits unreliable, and as platforms for storage and distribution they can be difficult to maintain. When Megaupload was shuttered in January 2012 following a raid by the United States Department of Justice on charges of facilitating copyright infringement, many fan edits that were coincidentally housed on Megaupload's servers were irrevocably lost. Similarly, the December 2014 raid by Swedish law enforcement on the popular BitTorrent indexer The Pirate Bay consequently disabled access to many fan edits.

[1.6] Problems in accessibility have also been exacerbated by the association of prominent persons in the entertainment industry with fan editing. For example, it is likely that demand for illicit DVD copies of The Phantom Edit increased when filmmaker Kevin Smith was initially suspected to be its maker (Wille 2014, ¶3.3). More recently, celebrity fan editors like Steven Soderbergh and Topher Grace have attracted a remarkable amount of public interest in fan editing, but they have notably taken steps to limit access to their work, most likely due to legal concerns (Sciretta 2012; Bernard 2014). I introduce the term vaporcut in this essay to account for intangible fan edits such as Grace's much-publicized yet unreleased editing projects.

[1.7] In response to the demand for inaccessible fan edits, some industrious fans resort to replication as a means of appreciating scarce works. However, the process of reconstructing fan edits, which typically involves retracing the steps of a previous editor, inevitably leads to creative variations. The following sections of this essay provide examples of how replicative approaches to fan editing have been the impetus for new transformative works.

2. Rebuilding and remixing Psycho: The Roger Ebert Cut

[2.1] In a review of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) that coincided with the release of Gus Van Sant's nearly shot-for-shot remake version, Roger Ebert (1998) criticizes Hitchcock's use of a psychiatrist character (Simon Oakland), whose monologue near the conclusion of the film diligently explains Norman Bates's (Anthony Perkins) psychosis. In defense of the scene, Wood (2002) argues that the psychiatrist's evaluation "crystallizes for us our tendency to evade the implications of the film, by converting Norman into a mere 'case,' hence something we can easily put from us. The psychiatrist, glib and complacent, reassures us. But Hitchcock crystallizes this for us merely to force us to reject it" (149). The original scene from Psycho is provided in video 1.

Video 1. Original ending of Psycho (1960), including the complete psychiatrist monologue.

[2.2] Ebert (1998) rejected the scene and described it as "an anticlimax taken almost to the point of parody" that "marred the ending of a masterpiece." He concluded his review by suggesting an alternative:

[2.3] If I were bold enough to reedit Hitchcock's film, I would include only the doctor's first explanation of Norman's dual personality: "Norman Bates no longer exists. He only half existed to begin with. And now, the other half has taken over, probably for all time." Then I would cut out everything else the psychiatrist says, and cut to the shots of Norman wrapped in the blanket while his mother's voice speaks ("It's sad when a mother has to speak the words that condemn her own son"). Those edits, I submit, would have made "Psycho" very nearly perfect.

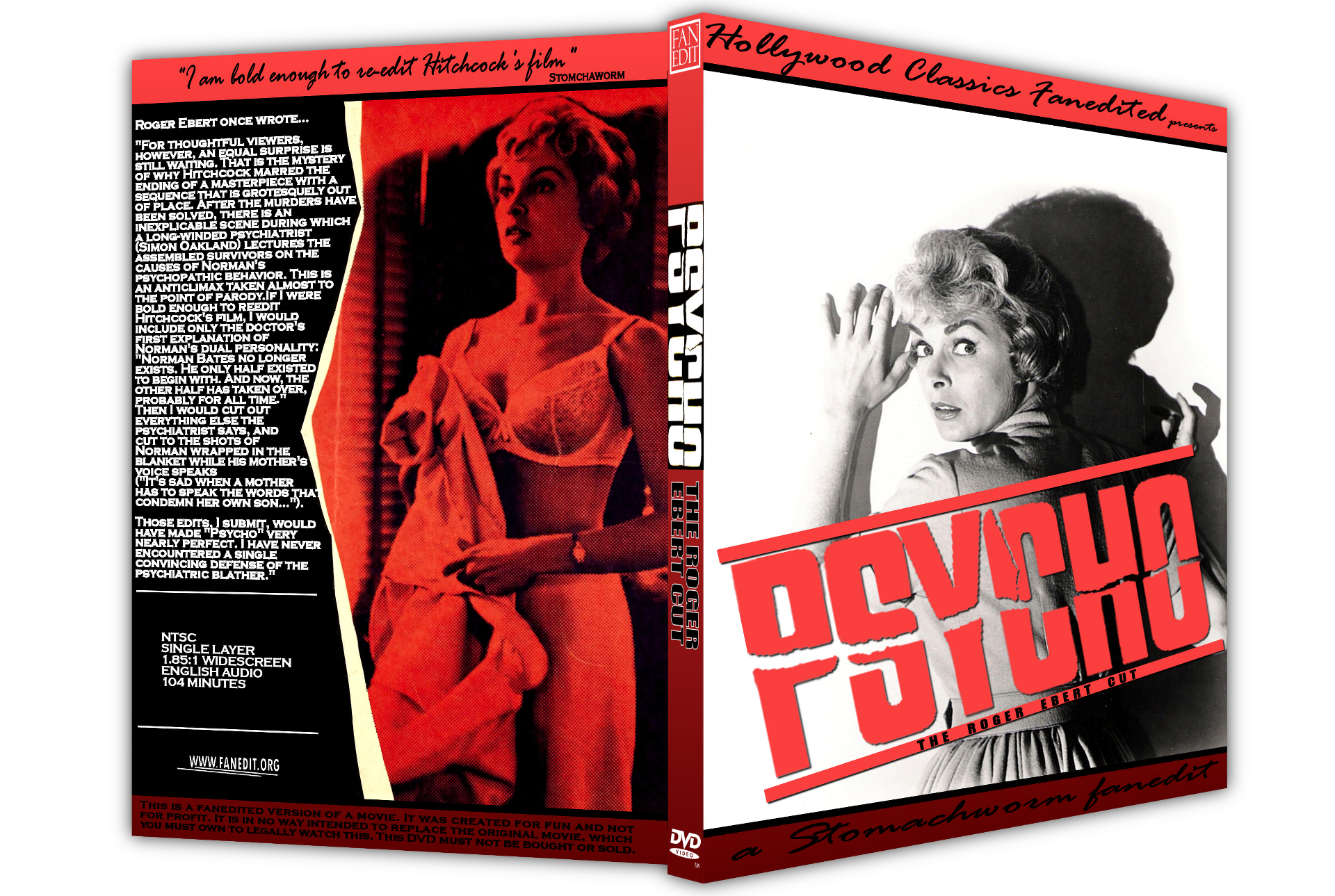

[2.4] In 2009, Stomachworm released Psycho: The Roger Ebert Cut, a fan edit that strictly adhered to Ebert's suggestions for modifying Hitchcock's film (figure 1). In a Twitter post on October 16, 2011, Ebert (@ebertchicago) acknowledged the work, writing, "I'm opposed to piracy but find this fanedit of 'Psycho' proves a point: Hitchcock didn't need the psychiatrist. http://t.co/wrzVhRBM." At that time, Ebert's tweet linked to a torrent that eventually became inactive and, like many torrents exclusively indexed by The Pirate Bay, this link to Psycho: The Roger Ebert Cut was also broken after the December 2014 raid. Because of the lack of access to Stomachworm's fan edit, I reconstructed Ebert's version (video 2).

Video 2. Ebert's speculative version of the ending to Psycho (1960) with a truncated monologue from the psychiatrist, reconstructed by Joshua Wille to substitute for Stomachworm's earlier work.

Figure 1. Three-dimensional mock-up of the custom DVD box art designed by CBB for Stomachworm's Psycho: The Roger Ebert Cut. [View larger image.]

[2.5] In the process of replicating Stomachworm's work, I was inspired to make another version of the conclusion to Psycho in which the psychiatrist is completely removed from the film. In this third version, Norman Bates is captured and moved to a holding cell at the local police station. Without a psychiatrist to lend any explanation of Norman's actions to the surviving characters or to provide treatment for Norman, he is hopelessly lost in his own mind with his mother's haunting voice (video 3).

Video 3. Alternative version of the conclusion to Psycho (1960) by Joshua Wille.

3. Steven Soderbergh and Heaven's Gate: The Butcher's Cut

[3.1] Since February 2014, Steven Soderbergh has released his own fan edits on his Web site, Extension 765 (http://extension765.com). The first was Psychos, a mashup of Psycho (1960) and Psycho (1998). Two months later, working under his film editor pseudonym, Mary Ann Bernard (2014), Soderbergh posted a reedited version of Michael Cimino's Heaven's Gate (1980), which Soderbergh claimed that he created in 2006. He restricted this and his other streaming videos from being embedded elsewhere on the World Wide Web or downloaded, which may have been a precaution against potential claims of copyright infringement.

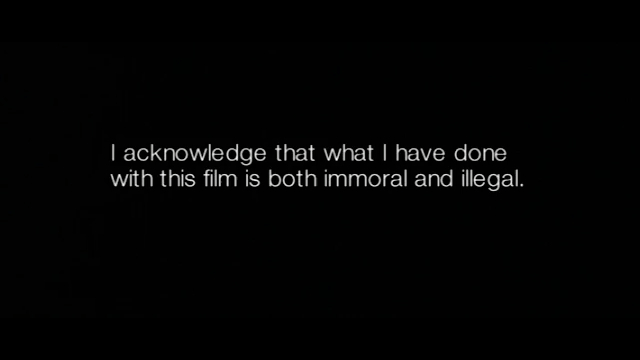

[3.2] Soderbergh's fan editing endeavors have been criticized by some as hypocritical because he was a prominent participant in a 2006 lawsuit that consequently shut down CleanFlicks, a company that resold unsanctioned versions of Hollywood films in which depictions of sex, violence, and profanity were edited out (Masnick 2015). Contemplating whether Soderbergh's fan edits would fall under the same fair use provisions that CleanFlicks unsuccessfully claimed in its legal defense, Post (2015) asks if Soderbergh "thinks that he has some kind of 'artistic license' to do what he denies to others, that his creativity is somehow more valuable than the creativity of others?" Perhaps in deference to those who might challenge his unauthorized version of Cimino's film, Soderbergh preceded this fan edit with a cheeky disclaimer (figure 2).

Figure 2. Screen grab of the disclaimer in Heaven's Gate: The Butcher's Cut by Mary Ann Bernard (Steven Soderbergh), which reads: "I acknowledge that what I have done with this film is both immoral and illegal." [View larger image.]

[3.3] Ironically, by attempting to limit the consumption of his fan edit, Soderbergh inspired further transformative work. Fan editor Take Me To Your Cinema (2014), also known as TM2YC, wanted to appreciate Heaven's Gate: The Butcher's Cut but felt hindered by some of its technical deficiencies; it was based on an unrestored DVD edition of Heaven's Gate and highly compressed for online video streaming, which contributed to general degradation of its image quality. Thus, in August 2014, TM2YC released a frame-by-frame, downloadable reconstruction of Soderbergh's fan edit using the restored 2012 Blu-ray edition from the Criterion Collection (note 1). However, his process of reconstruction led to some variation from Soderbergh's version (figure 3):

[3.4] While every care has been taken to reproduce the 180 or so visual cuts exactly, some shots differ by a frame or two. This is due to tiny differences in the source movie from the DVD to the Blu-Ray. I have also tried to reproduce the "spirit" of Soderbergh's soundmix. However, I've made my own adjustments to the mix, to further smooth transitions and improve small areas, when I thought it necessary. (Take Me To Your Cinema 2014)

Figure 3. Split screen that compares a frame from Heaven's Gate: The Butcher's Cut by Mary Ann Bernard (aka Steven Soderbergh), which was based on an unrestored DVD edition of Michael Cimino's film, and the reconstruction by Take Me To Your Cinema, which was sourced from the restored Blu-ray edition. Image: Take Me To Your Cinema. [View larger image.]

[3.5] As of this writing, Soderbergh has released two more fan edits since Psychos and Heaven's Gate: The Butcher's Cut, and he has received a listing in the Internet Fanedit Database (http://www.fanedit.org/ifdb/jreviews/tag/faneditorname/steven-soderbergh) that includes custom DVD art for his projects provided by TM2YC. Raiders (2015), for which its accompanying blog post bears the disclaimer "Note: This posting is for educational purposes only," presents a meditation on film direction and editing rhythms by rendering Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) in black and white as well as rescoring the film with music by Trent Reznor (http://extension765.com/sdr/18-raiders). Reflecting on this transformative approach, Soderbergh playfully retorts, "Wait, WHAT? HOW COULD YOU DO THIS? Well, I'm not saying I'm like, ALLOWED to do this." This humor continues into a subsequent blog post in which he introduces The Return of W. De Rijk (2015), in fact a fan edit of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Soderbergh later removed that fan edit from his blog (http://extension765.com/sdr/23-the-return-of-w-de-rijk) "at the request of Warner Bros. and the Stanley Kubrick estate."

4. Coup de Grace: variations on a vaporcut

[4.1] It has been widely reported (Sciretta 2012; Cheney 2012; Goldman 2012; Ryan 2012; Doctorow 2012) that actor and Star Wars fan Topher Grace reedited the Star Wars prequel trilogy to form one 85-minute fan edit entitled Star Wars Episode III.5: The Editor Strikes Back. Grace's project, which he has never publicly released, inspired the production of several variant works that generated further discourse (Ratcliffe 2014; Lambert 2014; Jagernauth 2014), including this sardonic exchange in the Fanedit.org (2014) forums:

[4.2] DominicCobb: How/why did this gain so much publicity?

T-Bone: I blame Topher Grace…he invented fan editing, didn't he??? But yeah, from reading up, apparently whoever did this one was heavily influenced by Grace's much hyped hardly seen PT [Star Wars prequel trilogy] edit.

[4.3] Two years earlier, Sciretta (2012) praised Grace's work as "probably the best possible edit of the Star Wars prequels" and recounted how he had joined actors, filmmakers, and other glitterati at an exclusive screening in Los Angeles:

[4.4] The screening last night was a private gathering of Topher's industry friends—an event that feels like it will surely become part of Hollywood quasi-urban legend. I wish you all could see Topher's version of the Star Wars prequels, but we were told that this would be the one and only time he would screen his cut. Of course, there are tremendous legal issues which would prevent him from screening the edit in public. He has no intention of uploading the footage online, and doing a screening at, say, Comic-Con, would require uncle George's permission—which probably would never happen.

[4.5] In lieu of a public release of The Editor Strikes Back, Sciretta (2012) provides a description of its alternate narrative structure, adding that "Grace hopes that other actors, editors and filmmakers will run with the ball, produce and showcase remixed films on a annual basis within this private community." Although no such group has apparently formed, Grace's editing projects remain inaccessible to those outside of his social circle (note 2). As evidence of his work, Grace posted a trailer on his blog (http://cerealprize.com/trailers/redux-of-the-jedi), but like Steven Soderbergh's version of Heaven's Gate, access to the video was restricted to his own Web site.

[4.6] Perhaps the term vaporcut could describe a much-publicized fan edit like The Editor Strikes Back that is made unavailable to fans. In a Twitter post on October 3, 2014, fan editor HAL 9000 (@KirkAFur) referred to The Editor Strikes Back as vaporware, a term commonly used in the computer industry to describe software and hardware products that are publicly announced but not actually manufactured or released. In discussions about the "George Lucas Generation" and a wider acceptance of film revisionism, digital cinema has been compared to software because of its mutability (Solman 2002, 22); thus, it follows that more computer terminology could be adapted to describe aspects of transformative media. As the concept of reediting films and television shows becomes more commonplace, the term vaporcut may prove useful in subsequent discourse for differentiating authentic fan edits from unsubstantiated works (note 3). This is not meant to suggest that The Editor Strikes Back is a hoax, but it has not been released outside of Grace's coterie of friends and industry professionals. Because its existence cannot be independently verified, it is disconcerting that an unsubstantiated work has been widely accepted at face value. In order to conscientiously study fan edits, we must not give credence to sensationalism about unproven texts (note 4). The Editor Strikes Back is a vaporcut because it exists merely in rumors recycled by entertainment blogs and through the conjecture of fans who read them. In spite of this fact, "Topher Grace is typically credited with starting the trend of re-cutting the Star Wars prequels into one movie" (editorbinks 2015).

[4.7] Quite the contrary. There are various fan edits predating Grace's vaporcut that combine the films in the Star Wars prequel trilogy, but they contain more extended versions of the narrative. For example, Blankfist's Star Wars—Fall of the Republic (2007) runs 180 minutes; Lewis866's Star Wars: Rise of the Empire (2007), 240 minutes; The Man Behind the Mask's Star Wars 30's Serial Edition Part 1 (2008), 132 minutes; Insignia34's Star Wars: A New Beginning (2010), 95 minutes; and JasonN's Shadows of the Old Republic (2010), 147 minutes. Moreover, all subsequently released prequel trilogy edits are longer than the reputed 85-minute runtime of The Editor Strikes Back.

[4.8] The promulgation of The Editor Strikes Back since 2012 has compelled some fans to create surrogate works based on what Grace reportedly accomplished (note 5). Often, these replicative fan edits were initiated because fans wanted to see for themselves what is essentially nonexistent: Topher Grace's vaporcut. Unlike TM2YC's reconstruction of Heaven's Gate: The Butcher's Cut, for which there was a reference text on which to base his work, the intangibility of The Editor Strikes Back required fan editors to make significant creative decisions. Thus, fan editors' efforts to realize Grace's vaporcut produced a series of variants that reflect more of their personal visions of a Star Wars prequel trilogy edit than the unattainable object they attempted to replicate.

[4.9] In May 2014, Double Digit described their 167-minute Star Wars: Turn to the Dark Side—Episode 3.1 as "a reimagining of the Star Wars prequel trilogy edited into a single movie, based on the structure conceived by actor Topher Grace." In the same month, Jared Kaplan's similarly designed 129-minute Star Wars: A Last Hope also appeared. In October 2014, Double Digit produced a second version of Star Wars: Turn to the Dark Side that runs approximately 160 minutes, while TJTheEmperor released a 208-minute prequel trilogy edit entitled Star Wars: The Fall of the Galactic Republic. The following month, Andrew Kwan (2014) released a 124-minute edit, Star Wars I–III: A Phantom Edit, which he explains was based on "the format description of Topher Grace's edit." Like those fan editors who preceded him, Kwan most likely attempted to conform to Sciretta's synopsis of The Editor Strikes Back, but through some creative divergence he produced a unique permutation (note 6).

[4.10] There have also been creative responses to the trend of replicating Grace's vaporcut. In December 2014, Zantanimus produced Star Wars: The Last Turn to the Dark Side, a hybrid cut that combines portions of Double Digit's Turn to the Dark Side and Kaplan's A Last Hope. The genesis of this project can be attributed to a May 10, 2014, Twitter post by disingenius (@disingenius), who suggested that fans should watch A Last Hope until 1:15:02 of its run time, then continue with Turn to the Dark Side from 1:19:59 to its conclusion. Zantanimus (2014) shared his initial assembly of The Last Turn to the Dark Side with fans on Reddit and announced plans to recreate it using Blu-ray source material; the subreddit /r/starwarsprecut (https://www.reddit.com/r/starwarsprecut) tracks the development of this shot-for-shot reconstruction. However, in introducing their own 140-minute project Star Wars: A Vergence in the Force, editorbinks (2015) criticized works like Turn to the Dark Side and A Last Hope: "A few fan edits were made in the spirit of Topher Grace's cut, but none of them fully satisfied me. They went on too long or the quality of the editing wasn't strong enough. They also cut too much out of Episode 1. I decided to do one myself" (note 7).

[4.11] Ironically, Topher Grace's The Editor Strikes Back has made fan editing practice more accessible despite the work itself being inaccessible. The sheer prominence of The Editor Strikes Back, a fan edit made famous because of its famous creator, overshadows the tangible fan edits it inspired. This dysfunctional effect is somewhat akin to the breakthrough of The Phantom Edit, a complicated case that propelled fan editing into the mainstream. However, as cultural touchstones, both The Phantom Edit and The Editor Strikes Back continue to distract from an expanding body of innovative work made by other fan editors (Wille 2014, ¶1.6–7).

5. Conclusion: Access redefined

[5.1] Like other transformative practices, fan editing continues its development amid ongoing challenges to accessibility that are complicated by legal and ethical disputes in online media. Because of their technical characteristics, fan edits are typically distributed through the same channels as are pirated works. However, when BitTorrent indexers and file lockers are seized by law enforcement agencies on grounds of piracy or are otherwise deactivated, fan edits like Psycho: The Roger Ebert Cut can be counted among the collateral damage. In other cases, access to high-profile projects such as Heaven's Gate: The Butcher's Cut and The Editor Strikes Back may be intentionally restricted by their creators. Fan editors have attempted to manually recreate these elusive works, but they naturally produce variants that reflect their own creative choices, similar to the way in which an inspired cook may deviate from a recipe.

[5.2] As an example, in December 2014, Mike Furth published instructions for making Marvel Movie Omnibus—Phase 1 and Marvel Movie Omnibus—Phase 2, which are chronological fan edits based on the films and television series in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (note 8). In addition to listing precise time codes from each source, Furth provides companion videos that guide fans through the editing process and invite them to modify the work to fit their own tastes (video 4).

Video 4. In this video, Mike Furth discusses the various cuts and combinations involved in making Marvel Movie Omnibus—Phase 1 and superimposes relevant time codes from each video source on screen. Furth also released a subsequent video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adTQ8KrYozM) to accompany Marvel Movie Omnibus—Phase 2.

[5.3] The aforementioned home-brewed replications of fan edits, which stimulate creative variation, are procedurally different from the way in which most professional video projects are cloned between multiple parties by sharing software-based project files and edit decision lists (EDLs). These crucial files record every cut, trim, and reconfiguration of media in a video editing project, and subsequent editors can use them to reproduce the same project by automatically conforming (autoconform) identical source material. In answer to the access problems and regenerative fan editing described in this essay, further research could explore the potential for fan editors to circumvent some technical and legal obstructions by sharing customized project files or EDLs with other fans who would autoconform their own copies of fan edits using relevant source texts.