1. Introduction

[1.1] On November 24, 2013, 50 fans of Doctor Who (1963–1986, 1996, 2005–) congregated at London's Bloomsbury Ballroom to take part in "one of the biggest sci-fi themed weddings in Britain" (Sharp 2013). Couples from as far away as the United States and Canada traveled to engage in this mass-mediated ceremony that encouraged them to dress up in TARDIS-patterned wedding gowns, homemade Cyberman costumes, and suits inspired by various incarnations of the Doctor (figure 1). According to the Daily Mail, experience company Special Events coordinated the mass Doctor Who–themed wedding to coincide with the show's 50th-anniversary festivities that also included the worldwide premiere of the hour-and-a-half-long episode, "The Day of the Doctor" (2013). With the event's price tag of £2,000 (not taking into account the cost of travel and hotel arrangements), the participants were given a commemorative ring, complimentary Doctor Who–themed tattoos, prizes for best costume, a five-tier TARDIS cake iced with all 50 couples' names, fish finger and custard cupcakes, and a mediated ceremony led by a minister wearing Gallifreyan robes. The company's Web site, which had been developed for fans to sign up and be selected among the 50 to be in the mass ceremony, also included the chosen couples' profiles and stories about how they met and were joined in their love for Doctor Who (https://web.archive.org/web/20141218193141/http://whovianwedding.com/). Additionally, Special Events opened the festivities up to the public at £10 a ticket, most likely as a way to ensure a larger audience of fans and to increase community building and consumer loyalty with Doctor Who during this momentous occasion in its fandom.

Figure 1. Doctor Who fans dressed as their favorite characters come together to be married in one large ceremony in London. Photograph by Tolga Akmen, November 24, 2013. [View larger image.]

[1.2] While some might argue that such mass themed weddings are rare occurrences (note 1), individual fandom-themed weddings have become an increasingly popular spectacle on the Internet. This display not only exists on Pinterest where users have dedicated entire boards to collecting images of fandom-inspired weddings but also on fan Web sites (such as When Geeks Wed and Offbeat Bride, as well as numerous Wordpress blogs) entirely devoted to cataloguing the themed weddings of fans and retelling their stories of wedded bliss. Reality shows about brides and weddings have also been a consistent part of television programming, and while most do not depict fan weddings, some have shown people with fannish inclinations planning their nuptials. In an episode of BBC3's Don't Tell the Bride (2007–15), one couple incorporated elements of Harry Potter in their ceremony by having a Dumbledore look-alike drive the bride to the park where the couple said their vows. Even with this in mind, little research has actually been done on the presence of fandom in wedding culture. From large-scale events to more intimate ceremonies, examining the choice of fans to perform in themed weddings can shed further light on how they construct, define, and maintain their identity in a public space where not everyone might be a fan. In the case of the Don't Tell the Bride couple, the groom's affiliation with Harry Potter fandom inspired him to include fandom elements into the ceremony. The bride, on the other hand, noted how much she hated the idea of a themed wedding but came around to it because her soon-to-be-husband "really proved himself with what he did" (Collinson 2014). Even in the presence of nonfans, fandom can reveal further meaning behind a couple's identity. The performance of fandom, particularly in weddings, seems to be a place where we can further study how fans communicate the complexities of their identities in heteronormative spaces.

[1.3] Because this topic can extend to many different fandom-themed (and even multifandom-themed) weddings, I would like to primarily focus on the Doctor Who fandom because of its appearance in both individual themed weddings and its most recent venture into mass weddings captured by the media in order to discuss the various ways in which fans perform. Using scholarship on fan performance, identity, and fan consumption practices, I will first examine how Doctor Who fans consume and utilize products in the wedding industry to aid in their performance of fandom. The meaning assigned to the pop culture capital incorporated into their performance plays a large role in shaping and maintaining fan identity in the normalizing, consumer-driven industry dominant within wedding culture. Secondly, early scholarship on fandom as an empowering tool to subvert the mainstream will explain as well as complicate how we see fans negotiate traditional Western customs with their own personal, subcultural desires in the wedding ceremony. Finally, how Doctor Who fans display images of themed weddings on the Internet and take part in large spectacles like the mass Doctor Who wedding will provide perspective on how fans use their identity and familiarity with online fan communities to further define themselves in typically nonfandom spaces.

[1.4] Studying Doctor Who's presence in wedding culture also works in light of its flexible themes and styles that have allowed fans to adopt as many or as few fandom-related elements in their wedding as they would like. From TARDIS cake toppers to something as subtle as a blue garter, fans have found that Doctor Who provides many thematic and aesthetically pleasing elements to incorporate into their weddings. As one fan put it on the Portland Wedding Coordinator blog:

[1.5] Ultimately, Doctor Who is a romantic, idealistic show that is more about the magic of positive thought than straight-up technical sci-fi. The time travel trope makes it easy for any fan to find a motif, subtle or overt, that works for their wedding. What better way to show your love than to promise one's beloved "All of time and space"? ("Portland Wedding Coordinator Loves" 2013)

[1.6] In adopting various themes and items inspired by Doctor Who, fans are choosing how to perform this identity to the rest of their wedding guests (who may or may not be fans) as well as to critical fans on the Internet with whom they might share photos of their special day. But do these fannish items in the ceremony need to carry meaning strictly for the fans, or does this meaning also have to extend to nonfans as well? Because the focus of wedding ceremonies can go beyond the couple and attempt to show the joining of two families, it seems important to consider how these other communities might affect the way a couple might present themselves as fans. Doctor Who has gained popularity beyond the United Kingdom (indicated by the worldwide broadcast of the 50th-anniversary episode), but specific details and memories from the show's tenure might be lost on individuals who do not watch Doctor Who or even new fans who have yet to explore the show's vast canon. As a result, fandom carries certain limitations and considerations for fans of themed weddings who may want their guests to understand and enjoy the meaningful elements in their ceremony but who might encounter complications in doing so. The choices that fans must make when performing their identity in these social spaces become crucial to the construction of their identity as fans, allowing them to become closer to the text as a result of meticulously picking out which themes and symbols from fandom resonate the most with who they are as a couple. However, the construction of that identity in wedding culture faces complications because of how the ceremony also serves to satisfy the people close to the couple being married. Through investigating the performance of fandom in wedding culture, we can better grasp how fan identity is negotiated and even shaped within these controlling heteronormative settings and communities.

2. Performing all of time and space

[2.1] The performance demonstrated in wedding ceremonies depends heavily on how individuals choose to represent their identity and interests to others. Several scholars in fan studies have recognized this but in the more general context of fans performing for other audiences. Cornel Sandvoss has noted that "performance implies the existence of an audience for fan consumption and a process of interaction between performer and spectators" (2005, 45). Rebecca Black and Steven Thorne have also recognized that "identity work is not something that is done alone" because performances attain social significance when recognized or rejected by other people (2011, 257). Within these interactions the performer realizes the expectations of the spectator for the performance and manipulates his or her behavior or actions to account for these expectations. If we solely rely on this logic, the construction of a fan's identity through performance relies on the reaction of others. The same might be said when fans perform their identity in the context of a wedding ceremony. For instance, the presence of guests not associated with fandom might compel the couple to adhere more strictly to tradition than they would like. However, something else happens here in the construction of that identity.

[2.2] Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz elucidates how the performers construct their identity in a wedding ritual, asserting that rituals often serve as "a vehicle" for expressing one's identity because "each bride and groom is given an opportunity to create and then display (or perform) in public their own story (or narrative)" (2002, 129). Essentially, the couple demonstrates "where they have come from, who they are now, and who they wish to be in the future" (129). Leeds-Hurwitz further argues that it is "the use of symbols in performance that makes them meaningful; active participation in a performance gives it significance, not the mere fact that a ritual presents specific messages in a specific form" (2002, 102). The act of performing the object of fandom becomes an important part in the construction of identity because fan performances are in fact "performances of symbols and images representing texts" (Sandvoss 2005, 51). Although the presence of guests outside fandom might influence the way in which a couple performs their fan identities in the ceremony, the inclusion of certain symbolic objects from a particular fandom assigns deeper meaning to the construction of their identities because it conveys how fans will still incorporate personal interests despite their guests' expectations for a traditional ritual.

[2.3] Though labeling a themed wedding as a form of cosplay, or costume play, might be a stretch, certain politics behind cosplay's performativity can be applied to the development of fan expression of symbolic objects in rituals. Fan scholar Nicolle Lamerichs describes cosplay as something that "motivates fans to closely interpret existing texts, perform them, and extend them with their own narratives and ideas" (2011, ¶1.2). The costume becomes a "cultural product that can be admired at a convention, and therefore spectators also play a role in guaranteeing authenticity" (¶2.2). Fans who construct costumes modeled after a favorite character often do so in the context of a convention or some other fan-related event. When that context shifts to a wedding—a typically nonfandom space—the fan might no longer have an audience who will understand the implications behind these symbols. This might then imply that everyone involved in the ceremony should be a part of the bride or groom's fandom in order to guarantee authenticity and significance to the couple's fan identities. While some couples might encourage or instruct their guests to dress according to the wedding theme, most do not require this. This can often compel couples to become more discerning when deciding how they want to interpret their fannish desires to their guests. In turn, the selectivity that goes into incorporating fandom into a wedding creates more intimacy with the source material.

[2.4] It is in this moment of creating intimacy that fans revisit significant memories associated with the object of fandom, allowing them to maintain their sense of selves despite acting as consumers within the wedding industry. Where scholars of the Frankfurt School have contended that individuals become passive consumers when indulging in the deadening experience of mass culture, fan theorists have indicated that the collection and presentation of objects related to fandom can be an edifying experience for the fan (note 2). John Fiske champions this sentiment when he says that "the reverence, even adoration, fans feel for their object of fandom sits surprisingly easily with the contradictory feeling that they also 'possess' that object, it is their popular culture capital" (1992, 40). This popular culture capital provides fans with the "social privilege and distinction" needed to feel in control of their experiences as fans and as collectors of fan objects but also works to identify their "level of fandom" (Geraghty 2014, 181). In a themed wedding, fans might work to harvest as many unique objects of fandom as they can so that other fans might recognize them as true or hardcore fans. Even so, this is not the only way in which fans are able to create a closer relationship with the text. Scholars like Lincoln Geraghty and Henry Jenkins have recognized that through collecting items, fans experience nostalgia, creating "personal histories" that have "become embodied in the collected objects of popular culture" (Geraghty 2014, 4). Memories associated with the object of fandom make pop culture capital meaningful to fans and contribute to what Matt Hills has described as "the lived experience of fandom" (2002, 35). Fans not only develop these memories because of fandom but also because of the events happening in their lives at the time. While fandom-themed weddings might indicate the level of fan a person might be, it also does not completely explain how such weddings can still be meaningful to the couple themselves. The nostalgia that fans feel towards an object of fandom represents not just their experience as fans but also their experience as people who are influenced by their social and cultural surroundings, making it possible to maintain their fan identity in the traditional constructs of the wedding ritual.

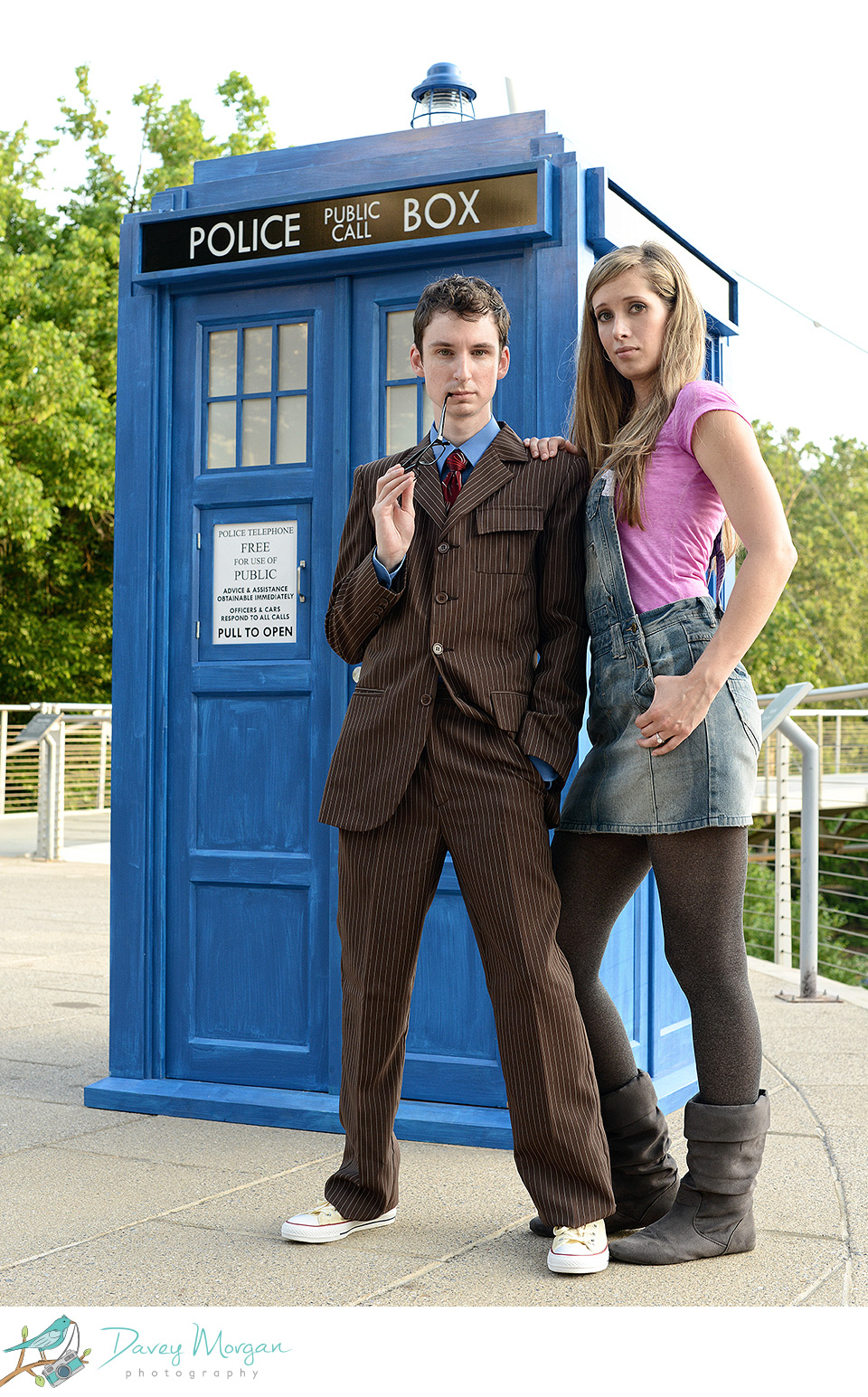

[2.5] To better illustrate this, I would like to examine one particular couple featured on the fandom wedding Web site When Geeks Wed who chose to have both a Doctor Who–themed wedding and a themed engagement photo shoot. For Laurie and Justin (figure 2), tradition still had a strong hold over how they wanted to conduct their wedding ceremony. The two chose to be married in a church while dressed in the white gown and black tux traditional of Western wedding customs, yet the use of the color blue in their decorations (a color symbolic of the blue police box that the Doctor travels in) and the TARDIS wedding cake (figure 3) were prominent features defining the couple's identification with the Doctor Who fandom. Closer inspection of more subtle motifs reveals that the bride's bouquet contained small, silver-colored rose and angel wing charms (figure 4) to represent companion Rose Tyler and the Weeping Angels, a race of monsters from the show. While these charms provided a small yet significant addition of Doctor Who into the couple's mostly traditional wedding, they also recalled certain memories for the couple, something that manifested itself in their engagement photo shoot showing the bride and groom dressed up as Rose Tyler and the Doctor (figure 5). Through this personal, shared experience in the couple's history, these Doctor Who elements gained significance by "socially constructing a situation in which the participants experience symbolic meanings" thereby showing how the rituals "gain their rhetorical force" (Leeds-Hurwitz 2002, 102). These subtle additions to the wedding ritual unearth memories not just about the couple's experience with Doctor Who (about which When Geeks Wed does not go into great detail), but also other memories about their time together that most likely involved Doctor Who to such a degree that it seemed obvious for them to incorporate elements of the show into their ceremony. Some of their attendees might not be aware of Doctor Who and its fandom, but they can at least recognize the significance of the couple's relationship and the shared passion they have towards fandom.

Figure 2. Despite adopting a Doctor Who theme for their wedding, the couple still retained traditional elements by posing for a photo in a church. Photograph by Davey Morgan. [View larger image.]

Figure 3. Laurie and Justin cut into a cake in the shape of the TARDIS. Photograph by Davey Morgan. [View larger image.]

Figure 4. Laurie shows off her bouquet depicting rose and angel wing charms, signifying companion Rose Tyler and the Weeping Angels. Photograph by Davey Morgan. [View larger image.]

Figure 5. The couple cosplay as the Doctor and Rose Tyler during their engagement photo shoot. Photograph by Davey Morgan. [View larger image.]

[2.6] For fans in everyday life, the acts of performing and producing objects contribute to the autonomy of the individual and ultimately stand as a source of stability and security in their identity (Sandvoss 2005, 47). Even more, fan performance takes on similarities with common social interactions, where the "world is constituted as event, as a performance" because the "objects, events, and people which constitute the world are made to perform for those watching or gazing" (Abercrombie and Longhurst 1998, 78). A wedding ceremony is one of many performances, a lived-out fantasy for people to don elaborate costumes and recite words in a meaningful display for guests. But in doing so, the wedding couple must determine how best to enact this performance based upon the scrutiny of their audience. For couples to then elect to have a fandom-inspired wedding and act out particular objects and themes from fandom further suggests that "fandom is not an articulation of needs and drives, but is itself constitutive of the self" (Sandvoss 2005, 48). Since people perform for others all the time in daily interactions, the self becomes a symbolic object that represents personal pleasures. Yet performance does more than just relay personal pleasures; it also compels the person to "incorporate and exemplify the officially accredited values of the society, more so, in fact, than does his behavior as a whole" (Goffman 1959, 125). Acting out one's fandom, whether in the context of a wedding ceremony or some other social event, certainly expresses an individual's interests. Yet the selectivity behind expressing these interests, often motivated by social pressures and expectations, further demonstrates that the fan wants others to perceive the symbolic objects that make up their identity in a socially acceptable way.

3. Something borrowed, something TARDIS blue

[3.1] Though some fans may feel restricted in how to perform their fandom interests in a wedding ceremony because of traditional obligations, others see fandom as a way to better express an identity not largely accepted by the mainstream. The idea of fandom empowering those marginalized by gender, race, class, and age had been popularized by the first wave of fan studies in the early 1990s (Jenkins 1992; Bacon-Smith 1992; Penley 1991; Tulloch 1990). At the time, this was partly because of fans' inability to significantly influence the texts they were consuming on television, in comic books, and in movie theaters. Since then, fan scholars have shifted away from this mindset, asserting instead that "fan audiences are now wooed and championed by the culture industries" and that we are entering an age where fans become the producers (Gray, Harrington, and Sandvoss 2007, 4). Digital marketplaces like Etsy and Redbubble allow fans to create products not sold in larger markets, ranging from fandom-inspired necklaces and iPhone cases to custom wedding invitations and engagement ring boxes (figure 6). Though independent sellers exist to provide fans with the materials they need to subvert the mainstream, fandom-themed weddings are still considered traditional.

Figure 6. This Doctor Who–inspired engagement ring box, featuring an LED light, is one of the many fandom-themed wedding accessories found on Etsy. [View larger image.]

[3.2] While adding a model of the TARDIS to the top of a five-tier wedding cake might not be a common sight, simply incorporating fandom elements into a wedding does little to actually subvert tradition. What these fannish alterations seem to provide are entryways for fans to comfortably perform the many facets of their identities, some of which might oppose tradition. By taking on the role as the other, the individual manages to "enhance the process of identity communication and interpretation. The other, in turn, grants symbolic recognition of the identity performance" (Altheide 2011, 8). When fans alter certain aspects of the wedding ceremony, their identity certainly becomes easier to recognize. It opens up further conversation on why people might have a fandom-themed wedding and allows fans to display parts of their identity that are significant in their opposition to heteronormative society. With this in mind, the intersection of fan identity and gender, sexual, and racial minorities can sometimes illustrate how and why fans feel an affinity toward texts that speak to issues of social and cultural oppression. Yet when a wedding couple chooses to incorporate fandom into the ceremony, they are not necessarily making a statement about subverting tradition. They are customizing their fan experience to make a traditional wedding more personal and more enjoyable for their unique identity. Fiske further situates fandom's significance in this event, saying that "on the one hand it is an intensification of popular culture which is formed outside and often against official culture, on the other it expropriates and reworks certain values and characteristics of that official culture to which it is exposed" (1992, 34). Fans may produce and change various aspects of a wedding ceremony to fit their own desires. They may even do so because they feel that their marginalized identities do not quite fit in mainstream wedding culture. However, they still do these things within the confines of society's cultural norms.

[3.3] While some may wish to not be affiliated with the institution of wedding culture, there are still some traditional aspects about fandom-themed weddings that actually uphold cultural conventions. Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington convey how fans can be characterized as people who are not a "counterforce to existing social hierarchies and structures" but who actually maintain these "cultural systems of classification" (2007, 9). In most Doctor Who–themed weddings, couples described how they still maintained elements traditional to their culture or had difficulty persuading their wedding guests to dress according to their theme. Even the couples that pulled off their Doctor Who–themed wedding without much grumble from their guests still adhered to a socially acceptable ritual structure. Returning to what Leeds-Hurwitz has to say about weddings, it becomes apparent that "although everyone is unique, and each ritual is different from every other example of even the same ritual, people are more comfortable if some elements repeat from variant to variant of a form" (2002, 62). If a couple deviated too much from tradition, the wedding ceremony might not be socially recognized in that couple's culture. Even so, the reflection of these cultural norms within fan alterations provides context for the couple's unique performance narrative, and in some ways adds further meaning behind their identity.

[3.4] For Clara and Justin (figure 7) featured on the fandom wedding Web site Offbeat Bride, the rejection of certain traditional elements was important to how they wanted to represent their Doctor Who–inspired wedding that also combined elements from Legend of Zelda, The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and various other fandoms. Though not fandom-related, they also opted to weld their own wedding rings rather than purchase them and even included a reading from the Rush song "Ghost of a Chance" during the exchanging of their vows. In describing how they planned their wedding, Clara said:

[3.5] We wanted our wedding to be as personal as we could make it. We tossed out anything we didn't feel connected to, like the garter toss, the first dance, and clinking glasses. Instead, we looked at each facet and tried to figure out how to make it represent one of our geek interests. ("Clara and Justin's" 2013)

Figure 7. While Justin dons a suit similar to that of the Eighth Doctor's, Clara chooses a unique dress that fits her personal taste. Photograph by J. F. Hannigan. [View larger image.]

[3.6] Though Clara and her husband left out old-fashioned customs in their wedding in order to accommodate their own personal interests, they still retained a traditional structure in how they officiated the ceremony. They still chose to photograph the first look, otherwise known as the first moment that the bride and groom see each other dressed up for the wedding. They even chose to have a flower girl and ring bearer walk down the aisle with them as many other couples do. Because Clara and Justin retained some of these traditional elements, we cannot confidently say that their fandom-themed wedding completely subverted tradition. Instead, we should ask how these fannish alterations provided significant meaning to their ceremony that might not have been the same if they had chosen a more traditional path. We can best explore this through another couple on Offbeat Bride, Emily and Greg (figure 8). Like Clara and Justin, Emily and Greg retained a traditional structure to their wedding that included a ceremony in a Catholic church and formal wedding attire (except for the Converse shoes they wore—a subtle nod to David Tennant's Tenth Doctor—their wedding does not heavily imply that there is a Doctor Who influence). Despite being held in a church, the couple made a point to request the Catholic-lite service that allowed them to include an Apache blessing at the end of their vow exchange. During the reception, they enforced a no clinking glass rule, a tradition where guests bang their silverware against their glasses until the couple stops what they are doing and kiss. Instead, the couple encouraged storytelling, allowing Emily to explain how her and Greg's values influenced their wedding:

[3.7] Our wedding toast started off with my commentary on how love, regardless of gender, sex, and preferences, should be accepted, and how traditional this wedding was despite the fact that I am happily bisexual and Pagan, and Greg is a reformed Catholic and "heteroflexible." We are also polyamorous. ("Emily and Greg's" 2013)

Figure 8. Other than the Converse shoes Emily and Greg wore in tribute to the Tenth Doctor, their wedding was mostly traditional. [View larger image.]

[3.8] For both couples, Doctor Who and other fandom interests provided a framework in which their unconventional attitudes or identities could exist. Additionally, it seems important to acknowledge that some couples who choose to have a fandom-themed wedding often do not fit into the heteronormative mold that wedding culture promotes. By putting on such a wedding, a couple can craft a performance narrative that can articulate preferences often marginalized in society (e.g., Emily's bisexuality). Other times a couple might just reject certain elements of tradition for reasons personal to their own experiences, like Clara and Justin who did not want to include the garter toss or clinking glasses. Either way, these couples managed to use both fandom and tradition to voice identities and ideals that had been previously silenced in society, illustrating how fans' experiences in fandom and in traditional structures influence the performance of their identity.

[3.9] Adopting certain fannish details in place of more traditional wedding elements also allows fans to further establish their social status as discerning consumers. According to Fiske, "Some fans, whose economic status allows them to discriminate between the authentic and the mass-produced…approximate much more closely to the official cultural capitalist, and their collections can be more readily turned into economic capital" (1992, 45). Fans may adopt certain elements of Doctor Who that resonate with their marginalized interests, but the fact that they are able to freely do so suggests that they do not necessarily gain status by simply subverting tradition. Their ability to dictate and tailor their performance narrative to their preferences indicates that fans, like everyone else, define their social status by operating within a socioeconomic structure. Depending on class and economic mobility, some fans have more freedom than others in what kinds of fannish elements to adopt in a wedding ceremony. This can be seen in the level of quality and detail that often goes into the ceremonies, as well as how some couples lack the proper resources or budget to have the perfect fandom-themed wedding. With this in mind, fan practice parallels Bourdieu's sociological theory of consumption (1984). Class positions, like social capital, education capital, and cultural capital, are interrelated but not identical (Sandvoss 2005). As consumers in the wedding industry, fans continue to maintain these social hierarchies and exercise, to certain extents, the privilege of being discerning customers seeking to gain cultural capital. Yet according to Sarah Thornton, such fan practices might best be classified as "subcultural capital" which is "embodied in the form of being 'in the know'" (1996, 11). The actions that some fans take in purchasing wedding items made by other fans or even creating these items themselves add to the valuable experience of fandom because they ensure their active participation and status as devoted fans. While the meaningful objects that fans procure and integrate into their ceremonies can relay their social and economic status, these objects also illustrate how a fan's performance narrative gains cultural value among other fans, something which takes on further meaning when participation moves online.

4. Doctor Who gets married online

[4.1] Even more so now than before, wedding culture's online presence has simultaneously further embedded social expectations into people's consciousness and revealed how slight deviations from tradition can be possible. With the popularity of social media, fans performing in themed weddings are also performing their unique ritual for a larger audience, an audience that can appreciate the dynamics of an unconventional ceremony. Through this "highly mediated ritual," as cultural theorist S. Elizabeth Bird calls it, the wedding provides:

[4.2] scripts, imagery, and symbols that are often detached from the real personal lives of the people involved. The wedding speaks to the nature of a mobile, consumer-oriented society in which striving for unique identity is paramount, rather than the solidification of local family and ethnic identity. (2010, 94–95)

[4.3] As couples upload photos of their fandom-themed weddings, they are not only sharing a love for a particular fandom but also indulging in a shared experience that contributes partly to the pleasure of fan identity. Likewise, the economic context highlighted by Bird provides a significant perspective on how fan identity and the performance narrative are formed and maintained online. Access to more pictures, articles, and products for purchasing allows fans to pull from a greater pool of inspiration for their own fandom-inspired weddings. As such, fans become sensitive consumers in selecting various designs and items to incorporate in a ceremony and possess greater control over the formation of their own unique fan identity. This occurrence has been noted by Fiske, who asserts that fans are the most discriminating consumers and producers, and the "cultural capital they produce is the most highly developed and visible of them all" (1992, 48). The flexibility and exposure afforded to fans online offer more opportunities to personalize the fan community experience and produce a sense of camaraderie in hosting a fandom-themed wedding.

[4.4] The presence of an online audience can contribute to both the openness of fan expression in other social settings as well as to consumer discrimination among more critical fans. Both work powerfully in the construction of fan identity, but the latter can sometimes place greater pressure on fans who feel that their wedding must live up to the parade of other quality fandom-inspired weddings seen on the Internet. First, the presence of this mediated nature can contribute to Hills's "lived experience of fandom" because fans feel like they are performing for an audience of online fans who will appreciate their wedding perhaps more than their live audience of family and friends, some of whom may not understand the fandom references in the ceremony. It is through media and performance that fans use what Paul Booth and Peter Kelley describe as "augmented notions of the 'self' to address and publicly explore personal identity at a deep level" (2013, 64). By posting wedding photos online, fans can reflect further on this identity and how it situates itself between the fan community and other social arenas. The fandom-inspired wedding then becomes one of the few times that a couple can perform their personal fantasies and have them be recognized in a social and cultural context. Additionally, the reflexive and pervasive nature of reviewing photos of the wedding online solidifies and affirms this event as existing in both fandom and wedding culture. When we see images of fandom exist in a setting with which it is not normally associated, we begin to normalize fandom in that setting and to create a more open environment in which fan identity can be performed.

[4.5] Second, though the Internet may provide an open space in which fans can share these memories and feel a social connection to others, there still exists a level of judgment in the fan community and in mainstream culture on how fans go about representing their interests in a wedding ceremony. This occurrence seems to fall back on the accumulation of pop culture capital, where the discriminatory collection of objects (artworks, books, records, memorabilia, ephemera) can often delineate fan identity (Fiske 1992, 43). Some alternative wedding sites like Rock N Roll Bride illustrate attempts to achieve the perfect fandom-inspired wedding. In one article on constructing a mock Doctor Who wedding photo shoot, the writer describes the hunt for the perfect venue (something Victorian or futuristic) and the selection of an appropriate number of themes from the show. Other Doctor Who–themed weddings seen on the Internet, noted by the photographer, were either "really pretty, floral and sparkly, or a little too much like a cheesy costume party" (Forsyth 2013). The article also contained a fan video (figure 9) simulating two individuals meeting at a Doctor Who TARDIS display, falling in love over the course of six months, becoming engaged where they first met, and then arriving at the wedding ceremony location where they act out being attacked by a Dalek. While the video does not claim to be the epitome of what a Doctor Who–themed wedding should be, it does detail in the credits how Doctor Who fans found professional companies to contribute to the hair, makeup, floral arrangements, invitation stationary, confectionary, wardrobe, and props, illustrating the selectivity of pop culture capital and a framework by which other Doctor Who–themed weddings might be judged.

Figure 9. A still from a fan video shows a couple encountering a Dalek attack at their wedding ceremony.[View larger image.]

[4.6] With the pressure that some fans might receive from other fans over the Internet to capture the perfect fandom-inspired wedding, the performance narrative that develops as a result unveils significant community building in the fandom that attaches further meaning to the products that fans produce and consume. Regarding the fans who participated in the mass Doctor Who wedding, the Web site that promoted the wedding also contained the profiles for all 50 couples. These profiles provided details about how the couples met and why Doctor Who became a large part of their lives. For one couple, Jennifer and Klehlyn, multiple fandoms dominated their interests, but Doctor Who was the single fandom where "binge-watching entire seasons on Netflix [had] been a regular bonding activity for them" ("Our Couples" 2013). Through sharing their stories online where other fans could read them, these couples were able to profess their fan identity in an official way. By performing their fan identities online, featured alongside other couples ready to participate in the mass wedding, these fans strengthened their sense of community and devotion to the Doctor Who fandom. The couples' performance narratives in this mediated context provided "new levels of insight and [an] experience [that] refreshes the franchise and sustains consumer loyalty" (Perryman 2008, 26). The uniqueness of bringing together wedding culture with a significant moment in the Doctor Who fandom further exemplifies the accessibility of the Doctor Who franchise to its fans and how capitalist economies have begun to recognize shows like it to be financial powerhouses. As a result, businesses begin to cater to these fans, a practice that will continue to increase as fan production moves more and more online. From large events like the mass wedding to smaller online venues, amid growing media attention, the Doctor Who fan community is choosing to make a spectacle out of performance narratives, effectively making that spectacle an experience central to being a fan and participating in fandom.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] The presence of fandom in wedding culture provides a new way of understanding how and why individuals choose to express their unique qualities and experiences as fans. The process of creating and incorporating wedding objects into themed weddings makes it possible for fans to experience further affiliation with fandom as well as trigger memories that fans have with a particular text. The memories experienced by fans, from newcomers to diehard enthusiasts, come out of what the fans were feeling and doing at that time in their lives when they were engaging and participating with the text. Because of this, fans are able to blend the various memories they have of fandom into a meaningful performance narrative that extends beyond fandom and into other corners that make up their lives. It becomes possible then for fans to maintain their identity in a wedding ceremony because that identity encases their lives both inside and outside of fandom. We primarily see this displayed in individual fandom-themed weddings where fans do not take extreme measures to completely subvert tradition. For most, these weddings appear almost entirely traditional with the exception of a few changes to incorporate fannish objects and themes. The mass Doctor Who–themed wedding remains the exception where fans adopt more elaborate displays because of the increased expectation and attention they receive from other fans in person and online. As mentioned before, performances are based upon how the performers modify their behavior to suit the expectations of their audience. Because of this, the fans are influenced by both their experience in fandom and the traditional constructs that make up wedding culture. Fans' decisions to perform this identity in a wedding ceremony shows that fan identity encompasses more than just fandom. It also encompasses the negotiation they make when displaying this identity in heteronormative spaces.

[5.2] Because little has been written on fandom-themed weddings, additional research might expand upon the economies of fandom within wedding culture. Fans' consumption preferences and practices occur in a number of different ways in wedding culture. Fans may purchase commodities made by other fans or by capitalist markets, or they may even create these items themselves. However, risks still reside in how particular franchises choose to acknowledge and permit the production and activity of their fans as their presence continues to grow online. Cease-and-desist letters and copyright lawsuits have been known to interfere with fan labor products. As the acceptance of fandom weddings increases, it may prove interesting to explore how the wedding industry could affect the independent fan market and the construction of identity and performance in fan affiliation. For now it seems that some fandoms like Doctor Who are dedicated to celebrating the fan community through both commercial and independent efforts as well as presenting those participants with the materials needed to identify as fans and to integrate this persona into their everyday lives. It then seems important to understand how performance not only constructs fan identity but also maintains its value in a capitalist industry that threatens to diminish it.

6. Acknowledgments

[6.1] A version of this paper was presented at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association Conference in February 2014. I would like to thank Cathryn van Kessel, Aya Hayashi, and Elaine J. Basa for their generous critiques, my panel of fellow Doctor Who scholars at SWPACA for their support, and Dr. Tasha Oren for her last-minute revision suggestions.