1. Introduction

[1.1] In recent years, MTV has launched a series of reality TV shows in the United Kingdom. Emulating US series such as Jersey Shore (2009–12), Geordie Shore (2011–) and Desperate Scousewives (2011–12) have followed the everyday lives of 20-somethings in the north of England. MTV's first foray into Wales, however, saw the cast of The Valleys (2012–14) leave their homes in South Wales and head to the bright lights of Cardiff to fulfill their dreams.

[1.2] The Valleys premiered on September 25, 2012, but backlash against the series began when advertising for the show began. Criticism was aimed at MTV's use of cultural stereotypes in both the TV advertising (with the inclusion of mountains and sheep drawing on notions of Wales as rural principality and the Welsh as a nation of sheep shaggers) and the house decor (leek-themed wallpaper and sheep footstools and chairs). After the season premiere, this criticism intensified, with a Welsh newspaper, the Western Mail, calling it exploitative; MPs such as Chris Bryant taking to Twitter to announce, "That's not what the Valleys are like" (Williams 2012); and prominent Welsh celebrities, including Rachel Trezise, condemning the show for being "cynical, cheap, ignorant and by no means representative of the South Wales Valleys and people that I know and love" (Wales Online 2012).

[1.3] Grassroots criticism of the show also arose, however, with petitions created to cancel the series and scores of angry Twitter users taking over the program's official hashtag, #TheValleys, to air their complaints. A Valleys-centric campaign, The Valleys Are Here, created in direct response to the show, also took direct action, calling for MTV to donate 5 percent of their profits from the series to charities supporting deprived areas in South Wales, as well as creating their own films showcasing real people from the Valleys.

[1.4] In what I call antifan activism, antifans of a text—here, The Valleys—unite to protest it. The notion of antifan activism is not a new one; religious groups, for example, have campaigned to ban books such as the Harry Potter series (1998–2007) from public libraries, and domestic abuse charities have campaigned against the Fifty Shades of Grey (2011) trilogy. However, here I examine antifandom linked to a geographical and cultural identity—in this case, Wales and the South Wales valleys. This type of antifandom, while falling within Jonathan Gray's (2003) concept of antifans of a moral text, draws on Lawrence Grossberg's (1992) notion of affect as well as the ethical implications of a text to create a nuanced reading. This kind of antifan activism complicates current notions of fandom and fan practices, offering scholars of fandom new and intriguing ways to examine how audiences and texts interact and what can be learned from this interaction.

2. Framing antifan activism

[2.1] Fan activism has traditionally been regarded as fans acting together in order to extend or resurrect a group, film, or TV show in which they have an interest. Star Trek (1966–69) fans' letter-writing campaign of the 1960s, for example, would be considered a case of fan activism, as would The X-Files (1993–2002) fans' current campaign for a third film. More recently, however, focus has shifted to look at other methods of campaigning and activism within fandom (as evidenced by volume 10 of Transformative Works and Cultures, a special issue on fan activism published in 2010) and how celebrities and their fans have worked together to raise money and/or awareness for specific issues. Craig Garthwaite and Timothy Moore note that "it is clear that celebrities have the ability to influence the behaviour of their fans in other arenas" (2008, 5), and celebrities such as Gillian Anderson and Keith Duffy have mobilized their fan bases to promote charities and organizations. Actor Misha Collins, who plays the angel Castiel on Supernatural (2005–), used Twitter to ask his followers to donate money to the aid effort that followed the 2009 Haiti earthquake. Within 24 hours, fans had raised almost $30,000 and a nonprofit organization, Random Acts (http://www.randomacts.org/campaigns/), was created, which supported the country's reconstruction and which continues the funding of three orphanages. Lady Gaga has similarly used her position to encourage fan charity. During her Monster Ball tour, she partnered with Virgin Mobile to offer premium VIP tickets to fans who volunteered with homeless youth organizations. As a result, Gaga and her little monsters raised more than $80,000 (https://www.looktothestars.org/celebrity/lady-gaga).

[2.2] More fundamentally, however, fandom groups have also been created outside of any celebrity activity. "Aussie X-Files Fans" for Charity on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/axfcharity) has raised money for a variety of charities supported by Gillian Anderson (Jones 2012), and the Harry Potter Alliance (http://thehpalliance.org/) has also campaigned on a variety of issues, including rights to equal marriage and selling fair trade chocolate at the Warner Bros. studio. In each of these cases, the fandom has formed around an issue nominated by or affiliated with it, perhaps by issues raised in the text or by awareness raised by an associated star. Each of these examples, however, assumes that fan activism is only undertaken by fans of a book, show, or celebrity. I challenge this notion by adopting Jonathan Gray's (2003) definition of antifans to complicate ideas of fan activism.

[2.3] Gray has been instrumental in critiquing reception studies and reassessing the notion of audiences. He asks whether we can fully understand what it means to interact with media texts by only examining fans, arguing that focusing so intently on the fan distorts our "understanding of the text, the consumer and the interaction between them" (2003, 68). Instead, Gray suggests that we must also look at antifans and nonfans as "the very nature and physicality of the text changes when watched by the non-fan, becoming an entirely different entity…Non-fan engagement with the televisual text denies us the existence of the solitary, agreed-on text with which to anchor such discussions" (2003, 75).

[2.4] I focus here on antifans rather than nonfans, although I would suggest that the physicality of the text changes when watched by antifans as much as it does when watched by nonfans. For Gray, an antifan is someone who strongly dislikes a text or genre—someone who is "bothered, insulted or otherwise assaulted by its presence" (2003, 70). Antifans are not necessarily ignorant of the texts they hate, even though they may have not watched the show or read the book. Rather, they are aware of the text paratextually, through advertisements or reviews; they are aware of the genre and harbor a dislike for it; or they have seen similar shows and find them intolerable. However, antifans may also have watched or read a text—and may have done so as closely as fans do. Antifans of the Fifty Shades of Grey series, for example, often spork the novels—deconstructing the text and critiquing it in journals and blog posts (Harman and Jones 2013). These antifans are not only aware of the text through paratextual means but have also engaged in a close reading of it. They are often more familiar with the content and larger discussions than fans are.

[2.5] As scholarly work on antifandom increases, so too do the ways in which we understand antifan behavior and its similarities to fannish behavior. In the same way that fans undertake activism around texts they love, so too do antifans undertake activism around texts they dislike. Gray (2008) notes that all censorship campaigns are examples of antifan activism, and many such campaigns work: a threatened boycott of NBC by conservative Christian groups led to the cancellation of The Book of Daniel (2006) after only four episodes had aired, and the Monty Python film Life of Brian (1979) was banned in several countries because of its blasphemous depiction of Christ. It is likely that only since the notion of antifandom had been disseminated that these occurrences are considered antifan activism, but recent protests, such as those highlighted by the Racebending Web site (http://www.racebending.com), occupy a more firm space within theorizing antifan activism. Racebending was founded by fans of Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005–8) after casting decisions were made when adapting the series to film. The Asian and Inuit cast of the Nickelodeon cartoon was replaced predominantly by white actors in the 2010 film, and fans of the series protested these changes. The Racebending protest thus sees fans move from a position of fandom (in relation to the animated series) to antifandom (in relation to the 2010 movie and its depiction of race and gender). While fan and antifan activity is thus often placed on opposing ends of a fannish spectrum, it might be more accurate to say that that they exist on a Möbius strip, with "many fan and antifan behaviors and performances resembling, if not replicating, each other" (Gray 2005, 845). Antifans, like fans, also construct an image of the text—an image strong enough to cause them to react strongly against it. Gray concludes, "If we can track exactly how the anti-fan's text…has been pieced together, we will take substantial steps forward in understanding textuality and in appreciating the strength of contextuality" (2005, 845).

[2.6] The issue of contextuality is important in this examination of the relationship between MTV's The Valleys, the geographical valleys of South Wales, and reactions to the series from the people who live there. Contextuality plays an important role in antifan reactions to a text, one that has been undertheorized: merely stating that we need to appreciate the strength of contextuality fails to help us theorize the relationship that exists between antifans and texts. Melissa A. Click notes that the fan's relationship with a text is "a complex experience affected by the social contexts in which a text exists" (2007, 306); the same is true for the antifan. These social contexts play a role in determining the affective relationship that antifans have with the text. Writing about affect in fandom, Grossberg argues that "the fan's relation to cultural texts operates in the domain of affect or mood" (1992, 56). This is not in the same domain as emotion or desire; rather, it is more akin to a feeling. Affect gives color, tone, and texture to fan experiences. It is defined quantitatively by the strength of our investment in particular experiences, identities, and meanings, and it is further defined qualitatively by the way a specific event or text is made to matter to us (Grossberg 1992). Fans engage in affective relationships with texts they have a strong investment in and that matter to them. However, examining the reactions to The Valleys by members of the Welsh public also reveals strong investments in the meanings of the text; this subject matter is important to them. The public's experience of growing up and living in the Valleys provides color, tone, and texture to their experience of antifandom. Their relationship with the series is therefore an affective one, but it is in opposition to any fannish relationship.

[2.7] The role that affect plays in antifandom is an important point that Gray does not address, in favor of focusing on antifans of a moral text (note 1). In his study of Television Without Pity forums, Gray notes that many expressions of antifandom "were framed explicitly as moral objections to certain texts and frequently suggested the poster's only meaningful interaction with the text was at this hinge point of morality and what we would call the moral text" (2005, 848). These discussions revolved specifically around moral or ethical concerns, such as a TV movie on homeland security "taking advantage of a horrible tragedy [rather] than reporting the facts" (qtd. in Gray 2005, 848), and instead of expressing anger at a text for aesthetic, industrial, or factual reasons. Gray notes that these moral text viewers worried about other people's reception. He argues that this demonstrates that reception occurs with an imagined community of others, and thus "a good deal of what the text means to [viewers] is a reflection of what they believe it will mean to others and what effects it will have on others" (2005, 851). What Gray fails to account for in his analysis, however, is what the text means to the viewer and the effect that the text has on viewers and their physical community. Antifans of The Valleys object to the series because of their lived experiences and the effect that the show has on attitudes toward the Welsh in general, and thus themselves. This contrasts with the "third person effect" (Gray 2008, 63) encountered in many moral panics—for example, the so-called video nasty debate in the 1980s that posited that young people would be adversely affected by violence in video releases. Gray notes that antifans "may not feel that this instance of sex or violence, for example, will affect [them], but [they] may worry greatly for others" (2008, 63). Antifans of The Valleys, however are aware of the effect that the show may have on them in its reinforcing of historically oppressive stereotypes. These concerns are thus not simply, or rather not just, an engagement with the moral text. Instead, they involve a consideration of cultural, social, and political factors inherently connected to a specific location. In addition to antifans of moral or aesthetic texts, we need to consider antifans of a cultural text. The antifans deride The Valleys for portraying Wales in a negative and false light, and they do so on the basis of their lived experiences. These antifans are not simply voicing moral or ethical concerns, although these may form part of their criticism. They are voicing cultural concerns whereby their relationship with the text is affected by the social contexts in which the text is read and within which their own lived experiences reside. This is an important distinction. It affects the way we frame antifans and the importance these particular modes of activism have to fan studies.

3. Examining MTV's The Valleys and representations of Welsh identity

[3.1] The first episode of series 1 of The Valleys opens with the words, "This programme contains strong language and scenes of a sexual nature," with a voice-over noting the same in Welsh. This use of the Welsh language clearly positions the program as Welsh (note 2) despite figures from the 2011 census showing that only 562,016 people (19 percent of the population of Wales) self-identified as being able to speak Welsh (note 3). The scenes that follow also depict images of traditional Welshness: rolling valleys appear on screen to the sound of a male voice choir; the Welsh flag, with its distinctive dragon, rolls in the breeze; a Welsh town nestles in the shadow of a mountain as a voice-over states, "The Valleys, a place of myth and legend, where the dragon sleeps and life is beautiful." The soundtrack then changes to dance music, and different images of life in Wales flash across the screen. These depict the Valleys as run-down, desolate areas of high unemployment and antisocial behavior (figures 1–4).

Figure 1. The rundown White Hart Free House, with uncut grass and piled-up trash, in the Valleys from the opening of MTV's The Valleys, episode 1. [View larger image.]

Figure 2. Dumpster diving in an alley in the Valleys from the opening of MTV's The Valleys, episode 1. [View larger image.]

Figure 3. Graffiti in a neighborhood in the Valleys from the opening of MTV's The Valleys, episode 1. [View larger image.]

Figure 4. Boarded-up shops in the Valleys from the opening of MTV's The Valleys, episode 1. [View larger image.]

[3.2] These images are interspersed with clips of the series 1 participants discussing their life in the Valleys. Lateysha states, "There's nothing in the valleys. It is shit," while Aron notes, "I love being Welsh and I love being from the Valleys, but there's no opportunities there for us at all." Carley sums up her disdain for the area with three words: "Trackies, trainers, twats." The purpose of the introduction is not only to frame the series as a whole (eight young people moving to Cardiff to pursue dreams of modeling and DJing) but to frame the Valleys in opposition to the Cardiff setting. Participants note in the opening scenes that Cardiff is the place to be for anyone wanting to make a life, and shots of the newly developed St. David's shopping center stand in contrast to the closed pits and derelict buildings of the Valleys. While Cardiff may be the way out of poverty for some of the participants—Chidgey, for example, has worked on a building site since leaving school—club owner and mentor Jordan states, "You can take the kids out of the Valleys but you will never take the Valleys out of the kids" while scenes play of the boys downing alcopops, the girls licking each other's nipples, and everyone dancing on nightclub tables.

[3.3] A binary is thus created before the episode really begins that sets up the format of the remainder of series 1. Interviews with the cast continue through the first half of the episode, interspersed with clips of the cast entering the house and their initial interactions with other cast members. The overriding tone of the interviews is sexual; most cast members talk about the kinds of people they are attracted to and pass judgment on the other cast members. Leeroy and Lateysha in particular detail what they would like to do to each other, and the "coming up" snippets before the break feature participants kissing in various locations. The final two cast members, Carley and Liam, are introduced after the break. Both disrupt the tone set by cast interviews thus far. Liam acknowledges his homosexuality and asks, "What the fuck have I let myself in for?" upon entering the house and meeting his fellow housemates. Carley disrupts the tone by speaking Welsh (she is presented as the only Welsh-speaking housemate throughout series 1) for her introduction: "I'm from the Valleys and I like to get my tits out." Carley is also the only housemate who appears with a Welsh flag in the background in the interview sections. Carley thus disrupts notions of rural Wales as quiet—ideas promulgated by MTV itself that play into stereotypes about Wales.

Figure 5. Cast member Carley, running nude in a field while holding a Welsh flag aloft. [View larger image.]

[3.4] However, the series also refers to ongoing tensions about Welsh nationality. Rebecca Williams notes that the use of both rural Wales and the cityscape of Cardiff in science fiction TV program Torchwood (2006–11) "can be linked to ongoing tensions over Welsh nationhood since the opposition between rural Wales and the capital city can be seen as reinforcing negative stereotypes of Wales and potentially contributing to divisions based on geographical location" (2011, 64). Although the Valleys are not rural areas of Wales compared to, for example, areas of mid and west Wales (indeed, their history of industrial mining communities attests to an urbanized, industrialized locale), MTV depicts the Valleys and the people coming from it as coming from small villages and hamlets. The Valleys, in the discourse set up by MTV, is rural, in contrast to urban Cardiff, the big city where occupants of the Valleys come to fulfill their dreams. Tensions exist between the Valleys and the city in the series as well: mentor A.K. notes of the girls in the introduction to the episode, "They wear more makeup than clothes. Peeing in the street with a kebab in one hand a pint in the other hand." Liam, talking about the cast's behavior during a night out in Cardiff, says, "In amongst all this, I'm just thinking, like, this is totally embarrassing now. People are going to be thinking, like, who the hell are these Valley kids. They've come down to Cardiff making themselves look a right knob."

[3.5] Episode 1 shows the participants on a night out in Cardiff, but discussions in the house about going out into the city clearly demonstrate the housemates' familiarity with Cardiff. Leeroy mentions several clubs by name; Jenna acknowledges that Cardiff night life is completely different from that of the Valleys. This familiarity with the city contradicts MTV's preseries positioning of the housemates as being plucked out of their rural valley hamlets and placed into the big city, leading to questions about the reality of the series and the motives behind it. Thus far, the series follows the format of MTV's previous reality TV shows, but much is made in The Valleys of how there are no opportunities in the Valleys and how Cardiff is the center for anyone wanting a career. To that end, the housemates are fighting for an opportunity to work for Jordan Reed in PR and fulfill their dreams. Jordan, however, is shown watching the housemates during their night out at his club. In an interview segment, he notes, "Starting tomorrow, I'm their boss. Oh my god. I was expecting, you know, some real diamonds in the rough, but I just really forgot how rough the Valleys is." As Gill Branston states, Cardiff, "represented as cosmopolitan, English-speaking and urban," is "in perceived opposition to an indigenous, 'language-d'…and rurally rooted Wales" (2005, 114). Although few of the participants speak Welsh, Wenglish (from the portmanteau "Welsh-English"), the dialect used in the Valleys, is commonplace. Participants use words such as butt, cwtch, lush, and tamping, which differentiate them from Cardiffians and make them other. This is highlighted in a segment from episode 1 in which the film crew goes to Tonyrefail with Jenna and Chidgey. The phonetic spelling of the town is displayed below the street sign (ostensibly for English-speaking viewers, but it has the effect of depicting the place as other), and Jenna's dad's remarks are subtitled even though he is speaking English and does not have a particularly strong Welsh accent (figures 6 and 7).

![Color screenshot from The Valleys showing a dark-haired white man heading toward the open door in a housing unit, with two explanatory bars explaining what is going on. The top one reads, 'Tonyrefail,' and the bottom one provides the phonetic spelling/pronuncation, '[ton-reh-fel'].](https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/download/585/version/937/486/5206/figure-6.jpg)

Figure 6. The pronunciation of Tonyrefail is provided under the place-name in MTV's The Valleys, episode 1. [View larger image.]

Figure 7. Jenna's dad's words ("They'll have me to fucking deal with, simple as that") are subtitled although he is speaking English, in MTV's The Valleys, episode 1. [View larger image.]

4. Antifan activism: The Valleys Are Here

[4.1] Given this portrayal of the nation, Welsh response to the program was immediate and negative. Criticism was leveled at the lack of realism in the series. Many comments were made noting that relatively few of the participants came from the geographical Valleys. That a number of participants across the three series came from Swansea, Port Talbot, and Bridgend meant that many viewers thought that the series could not claim to be about the Valleys. This raises the question of what MTV considered the Valleys to be when they came up with the show's title and premise. MTV's decisions draw on cultural connotations of what the Valleys are and what people from the Valleys are like rather than a strict definition of the Valleys as a geographical place.

[4.2] Grassroots criticism via Twitter, MTV's Facebook page, and the Western Mail online escalated. Petitions were created asking for the show to be banned. A Valleys-centric campaign, The Valleys Are Here, sprang up after advertisements for the series aired in May 2012. The campaign was created by brothers Alex and James Bevan from the Rhondda. Introducing the campaign on their Web site, they write:

[4.3] Right, so now we know the MTV bandwagon has rolled into the Valleys to make their new unscripted—but heavily edited—"reality" TV show The Valleys, as a follow up to Geordie Shore. They've been busy tweeting and writing press releases about the area, but they don't seem to know what they're talking about.

[4.4] In case you missed any of this, MTV has already talked about the "tranquility of valleys life" and our "hamlet towns." Pretty bizarre stuff, as anyone who's spent more than 10 minutes in the area would know.

[4.5] So we want to make sure that MTV doesn't make any more slipups or give millions of people another bad image of the area.

[4.6] That's why we've started "The Valleys Are Here" campaign and website. It'll be fun, but at the same time give a positive picture of Valleys life—so look out for a stream of films, pictures, stories and loads more.

[4.7] Life here isn't all rosy, nobody would say that, but we're proud of where we come from—and want everyone to know why.

[4.8] Lots of people are already on board with the campaign, but we need you to help us set the record straight.

[4.9] So if you want to get involved let us know. We're looking for volunteers to help with the campaign in any way they can—and want every Valleys person to tell us why they're proud of where we're from.

[4.10] The Valleys are Here—be part of it! (https://valleysarehere.wordpress.com/about/)

[4.11] The Valleys Are Here Web site is designed to promote a more positive image of the Valleys; it features photographs, films, and stories of life in the area. The site contains a gallery of photographs of the Valleys taken by its residents, as well as stories about a range of organizations existing within and serving the Valleys. Among these are Big Click RCT, which helps older people within Rhondda Cynon Taff develop new skills to make the most of computer technology. On the Blick Click RCT page of The Valleys Are Here, the team writes, "At The Valleys are Here we've always said that not everything in the Valleys is rosy. The fact that too many people are still unable to get online, so miss out on all the advantages the internet brings (like being able to visit this site) is a real shame, but it's great that BIG Click RCT are doing something about it" (https://valleysarehere.wordpress.com/our-stories/big-click-rct/). Other organizations featured include the Merthyr Tydfil–based Central Beacons Mountain Rescue Team, made up of volunteers who provide a search-and-rescue service across South East Wales, and There Is More To (TIMTO), a social enterprise that began in Abercynon that enables family and friends to access a gift list that includes a donation for a charity of one's choosing. As well as the Web site, the campaign launched Twitter and Facebook pages to connect with prominent Welsh celebrities and organizations, to showcase stories about the good work being done in the Valleys, and to permit site visitors to contact MTV.

[4.12] The site serves as a center of information on the Valleys. It combats the picture drawn by MTV, but it also features a call to action. Prominent on the menu bar is a section called Join, which asks visitors to pledge their support by providing their details in a contact form so that the organization can keep in touch and add their names to the online wall, and Get in Touch, which provides visitors with a range of ways to contact the organization. A further call to action exists in the form of a petition that The Valleys Are Here created asking MTV to donate 5 percent of the profits from the series to local charity, Valleys Kids. Valleys Kids, a community regeneration charity, provides opportunities and activities across Rhondda Cynon Taff to enable young people to grow and develop, to have high expectations, and to achieve their potential. Discussing the campaign and the petition, the Bevan brothers note,

[4.13] When MTV announced that they were basing their latest "constructed reality" show The Valleys in our area, a group of us got together and formed "The Valleys are Here" campaign. We realised that the money made from Geordie Shore helped MTV's owners Viacom make huge profits last year, but the local area saw hardly any of this cash. So we think it's about time MTV showed areas like Newcastle and the Valleys some respect. (https://www.change.org/p/mtv-donate-5-of-profits-from-the-valleys-to-local-youth-charity)

[4.14] The petition received 1,100 signatures after the season premiere, rising to 2,500 by February 2013. Those who signed included MPs Vaughan Gething, Peter Black, and Christine Chapman, celebrities Johnny Owen and Rachel Trezise, and sport stars including Ian Vaughn, as well as members of the general public. A variety of reasons for signing the petition were given by supporters, but almost all talked about how MTV depicted the Valleys in a negative way, the use of stereotypes by the production company, or the exploitative nature of the series.

[4.15] The Valleys Are Here tweeted updates on the petition and sent an open letter regarding their request to Kerry Taylor of MTV on October 18, 2012. They continued to tweet at MTV asking about progress. In addition, they found out where MTV planned to film the second season and got to the location first. A reply did eventually come, but it skirted the issue of a donation, leading the campaign to begin discussions about a protest in London.

[4.16] The Valleys Are Here also created its own film about South Wales. On August 25, a month before The Valleys aired, The Valleys Are Here issued tweets and Facebook posts with information on filming and an open casting call. The film was designed to "throw the spotlight on the Valleys as we know and love them" (http://www.aberdareonline.co.uk/node/21074), and anyone living in the Valleys was invited to attend. Among those who turned up to the shoot were the Valleys Roller Dolls team, Rachel Trezise, and local businesses, charities, and families. The Valleys Are Here encouraged participation from various groups of people whose common denominator was their dislike of the series, but that dislike was not evident in the final film. Instead, the campaign showcased what people living in the Valleys thought of life there, as opposed to MTV's partly scripted, heavily edited series.

Video 1. Trailer for the film The Valleys Are Here.

[4.17] This film is particularly important for theorizing antifan activism. Some scholars have argued that social media has promoted a diluted form of so-called slacktivism (Christensen 2011; Morozov 2009) or clicktivism (White 2010), which fails to actively engage activists on an issue while nevertheless raising awareness on a larger scale. Actively appearing on film, however, requires a greater investment, which is where contextuality comes in. Gray observes that "hate or dislike of a text can be just as powerful as can a strong and admiring, affective relationship with a text" and can subsequently work to "produce just as much activity, identification, meaning, and 'effects' or serve just as powerfully to unite and sustain a community or subculture" (2005, 841). This distinction between dislike and affect, however, is problematic. Affect—at least in fan studies—has become synonymous with a fannish relationship, but we must reevaluate our understanding of affect. A distinction may be drawn between positive and negative affective relationships if necessary, but both exist. Furthermore, these negative affective relationships help shape antifandom of moral and cultural texts.

[4.18] The negative affective relationship that antifans have with The Valleys is related to their lived experience of being from the Valleys. This lived experience is detailed in many of the comments on The Valleys Are Here petition, as well as on Facebook posts, on Twitter, and in the campaign video itself. Howell Thomas narrates the documentary, demonstrating his knowledge of and affection for the Valleys with information on a variety of topics; author Rachel Trezise talks about her relationship with the Valleys; and Grogg producer Richard James Hughes talks about the importance of the Valleys to the genesis of the Grogg figurines. Those living in or coming from these communities are quick to refer to their own personal experience of the area as evidence of their authority to comment on the TV show—which also permits them to reject the show as a cultural text.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] Antifan activism provides scholars with new ways of understanding fan activism. Fan activism is not exclusive to people who consider themselves fans; activism is further complicated by drawing antifans into the equation. Fan studies scholarship needs to do more work to understand the complex ways that contextuality affects relationships between audience and text. Simply stating that we need to appreciate the strength of contextuality fails to help us theorize the complex relationships that exist, and more attention needs to be paid to the social contexts in which the text is read, as well as the roles that affect and the lived experience play. The Valleys antifans demonstrate the importance that lived experience has on the reading of a text and a subject's relationship to it; it also demonstrates the ways in which national and cultural identity can affect the content of antifandom and the form it takes. The Valleys is not a case of a moral text subsuming the aesthetic text. Many antifans of The Valleys, especially those involved in The Valleys Are Here campaign and documentary, are opposed to the text not because of its moral text in the sense that it is understood by Gray, or even the rational-realistic text; rather they are opposed to the cultural text, which frames Welsh and Valleys identity in a way that fails to present what they consider a true picture, and which presents a depiction of Wales that contrasts with antifans' lived experiences.

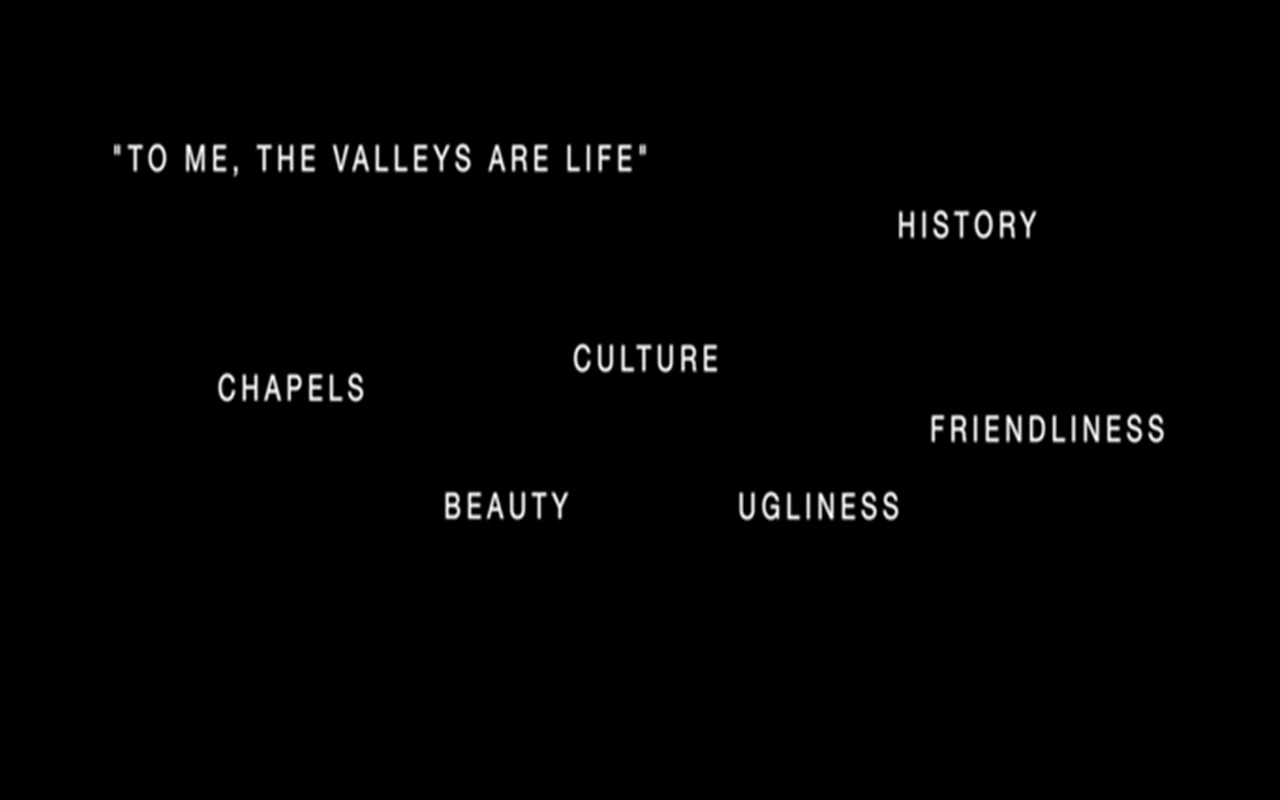

[5.2] Henry Jenkins (1992) asserts that common narratives no longer originate with the lived experience of members of a society but rather are created and distributed by publishing houses and production studios. Yet as this case study of The Valleys demonstrates, the lived experiences of antifans are used to create narratives that are used to counter these corporate constructions (Jones, forthcoming). Antifans of The Valleys use the depiction of Wales and Welsh identity promoted by MTV to create own narratives that rely on their lived experiences of the Valleys, countering what is shown on MTV. The Valleys Are Here documentary functions as a reframing device, one that seeks to reclaim a national identity. The documentary, with its specifically geographical focus—with references to culture and history as well as to good and bad lived experiences (figure 8)—as opposed to MTV's broad-brush Wales, allows for a response to the cultural rather than moral text of MTV's series.

Figure 8. Specific words from a voice-over highlighted on screen in the Valleys Are Here documentary highlighting good and bad lived experiences. [View larger image.]

[5.3] Although Kevin Williams argues that "the power to define Welshness has been at the center of the debate about the role of the media in Welsh society" (1997, 70) the response to MTV's The Valleys through campaigns such as The Valleys Are Here shows that the power to define Welshness is not limited to media producers or networks. Rather, ordinary citizens are able to define their own understandings of and experiences of Welshness, drawing on their lived experience and their affective relationship to place.

6. Acknowledgment

[6.1] I am grateful to Melissa Beattie for her comments on early drafts of this article.