1. Introduction

[1.1] Since the 1970s, George Lucas has influenced the passage of filmmaking into its digital era through his special effects company (Industrial Light and Magic), his contributions to nonlinear editing technology (such as the EditDroid system in the 1980s), and his production of primarily digital feature films, including the Star Wars prequel trilogy (1999–2005). The digital domain provided filmmakers with more expedient and economical means to tap previously unreached creativity, and Lucas often explains he was compelled to revise the classic Star Wars films in the 1990s because filmmaking technology was finally capable of realizing his original vision of a galaxy far, far away (Magid 1997, 60–70).

[1.2] Lucas has been criticized for essentially directing films from the editing room (Lewis 2007, 70–71), but it could be argued that his affinity for postproduction and his digital revisionism have helped the general public understand the malleability of the cinematic form. Contemporary revisions of films, as well as director's cuts and unrated versions in the home video market, reveal to audiences outside the film industry that a film is not frozen in a fixed shape; it is a dynamic "never-finished text" (Johnson 2005, 38). Earlier audiences, less well versed in industrial conventions, may have assumed that a film exists in a singular form, like a sculpture on its pedestal, but to the "George Lucas generation" digital cinema is like software in its mutability (Solman 2002, 22). Rojas (2002) observes that alternative film versions, which include Lucas's high-profile revisions of the Star Wars films, Francis Ford Coppola's release of the expanded Apocalypse Now: Redux (2001, originally released 1979), and Steven Spielberg's updated E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (2002, originally released 1982), "demolished the idea of a film as a single, finished product in the minds of the movie-viewing public. Instead we are headed towards a new conceptualization of a film as a permanent work-in-progress, which exists in multiple permutations, and can always be tinkered with in the future, whether by the director or by anybody else."

[1.3] George Lucas was certainly not the first director to "revisit his movies again and again, taking the canvas back off of the wall for another healthy dose of paint" (Griffin 2001b). In a November 12, 2013, e-mail to me, Kevin Brownlow recalled that D. W. Griffith frequently recut Intolerance (1916) at the Museum of Modern Art, much to the aggravation of the archive staff, and Abel Gance created controversial revisions of Napoleon (1927) in 1934 and 1971. Unlike earlier generations of filmmakers, Lucas pioneered digital media revisionism, and this technology was inherited by his audience. Traditional film editing equipment remains inaccessible to most people, yet basic nonlinear video editing software is now standard on most computer operating systems. Additionally, Lucas's revisionism seems rather hypocritical given that in 1988 he testified before the United States Senate against the alteration of culturally significant films (United States 1988) but 9 years later released the first digital revisions of the classic Star Wars films. Lucas spent approximately $10 million on the Star Wars Special Editions, arguing, "Films never get finished, they get abandoned" (Magid 1997, 70).

[1.4] Some fans may argue that poetic justice was served with the emergence of fan editing, an expanding form of media revisionism that affects more than just Hollywood products. In 2000, George Lucas was completing his first entirely digital feature, Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) while a fan using the pseudonym "The Phantom Editor" labored in secret, digitizing a videotape copy of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999) and recutting it on a desktop computer. In his alternative version, retitled Star Wars Episode I.I: The Phantom Edit, he trimmed and reconfigured shots to hasten the pacing and excised entire scenes, including several instances of slapstick comedy with the Jar Jar Binks character (note 1). Many Star Wars fans praised The Phantom Edit for attempting to rescue a disappointing cinematic milestone, while others opposed tampering with Lucas's work. After several months of controversy, The Phantom Editor was revealed to be Mike J. Nichols, a professional film editor living in the Los Angeles area. In a January 31, 2014, e-mail, Nichols told me that The Phantom Edit was simply intended for personal viewing, but a videocassette version that he shared with a friend was unexpectedly duplicated and distributed by unknown persons at parties around Hollywood in 2000–2001, and from there it spread onto the Internet. Nichols later remastered The Phantom Edit from a DVD source and also produced an edit of Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) before retiring from fan editing.

[1.5] In the years since the first appearance of The Phantom Edit, increasing numbers of fans have created new works from the pliable content inadvertently provided by Hollywood. In a January 17, 2012, interview with Bryan Curtis for the New York Times, Lucas reflected on his ambivalent relationship with Star Wars fans who recut his films: "On the Internet, all those same guys that are complaining I made a change are completely changing the movie. Why would I make any more when everybody yells at you all the time and says what a terrible person you are?" Later that year, Lucas sold his empire to the Walt Disney Company in a complex deal facilitated by a legal team composed mainly of Star Wars fans (Bond 2013). However, Lucas's dramatic exit from the Star Wars franchise is irrelevant to the fan editors, who have already exploited the inconstant fabric of Star Wars and many other films. Nearly a decade earlier, in a June 11, 2001, article by Andrew Rodgers (2001b), Star Wars fan Gerrig Thews had argued that "perhaps The Phantom Edit proves one thing…Lucas, for all his megalomaniacal goals, for his legions of lawyers securing the Lucas Arts logo, for his ownership of THX technology, no longer owns Star Wars." However, casting fan editors only as rebels against the authorial voices of Hollywood neglects the creativity of their emerging work.

[1.6] The purpose of this essay is to clarify some misconceptions about contemporary fan editing and provide a historical and critical foundation for further studies of the practice. Although The Phantom Edit was not the first reedit of a film or television show made by a fan, it was the one that "brought the art of fan editing into the mainstream" (Fanedit.org 2012), and I have observed that in casual discourse, social media, and various Web forums, "phantom edit" often serves as a metonym for "fan edit." Beyond Nichols's adept editing itself, the novelty of The Phantom Edit can be attributed to its cultural and technological circumstances. Based on Episode I, a highly anticipated and vexing film among Star Wars fans, The Phantom Edit had immediate appeal. Additionally, The Phantom Edit was perceived as a cutting-edge fan work because "The idea of housing enough hard drive space to edit a feature film in your apartment wasn't quite a reality then" (Nichols 2014, e-mail to author). Coinciding with the spread of peer-to-peer file sharing platforms like Napster, Gnutella, and BitTorrent in the early 2000s, The Phantom Edit appeared online at a time when a "confluence of trends in computer technology" (McDermott 2006, 256) enabled the free distribution of a professional quality reedit of a controversial feature film.

[1.7] Sensational depictions of The Phantom Edit as a fix or "corrector's edition" of Episode I (Lauten 2001) set a critical precedent for fan editing and shaped the dysfunctional legacy of The Phantom Edit. The enduring appeal and notoriety The Phantom Edit has makes it a common point of entry for aspiring fan editors who want to participate in the contemporary fan editing communities (L8wrtr 2010a; Baker 2012). However, academics, journalists, and others outside the fan editing communities continue to misunderstand it, although they often cite it in footnotes or brief discussions of fan editing (Weinberg Nokes 2004, 616; Pope 2004, 1046; Williams 2005, 163; Shields 2010, 104; Tryon 2012, 181–82; Howe 2012, 18). This essay seeks to realign scholarly perspectives on The Phantom Edit and fan editing in general.

[1.8] In this article I first examine the theory behind fan edits and then reconstruct the early reception of The Phantom Edit in order to explain why journalists, critics, and academics (DeLarge 2001; Gates 2001; Knight 2001; Weinberg Nokes 2004; Mason 2008; Young 2008; Tryon 2012; Klang and Nolin 2012; Phillips 2012) initially concluded that fan editing is merely a reactive fan practice. Admittedly, fan edits are partially reactive, because they are inherently comparable to their source texts and could be said to challenge traditional perspectives of authorship by demonstrating the malleability of digital media. However, instead of simply characterizing fan editors as disgruntled fans fixated on reclaiming films from their makers, we should recognize fan editors as a breed of artists and storytellers experimenting with cinematic media in the digital age.

2. Understanding fan edits

[2.1] We should recognize that a fan edit, like other transformative texts, creatively repurposes existing components. Booth (2012) observes that fan editing is at the center of Manovich's remix culture, "putting the creation of cultural products in the hands of amateurs, of users, of audience members, and of fans" (¶4.6). We may understand fan editing, like vidding and remixing, as an example of Lessig's (2008, 28) theoretical read/write culture put into practice. Although Balkin (2004) misrepresents the intentions of The Phantom Edit, he nevertheless recognizes fan editing practice as "another way of talking back…to a form of mass media that was, from its very earliest days, asymmetrical and unidirectional. It is not the passive consumption of a media product by a consumer. Rather, it involves a viewer actively producing something new through digital technologies. It exemplifies what the new digital technologies make possible: ordinary people using these technologies to comment on, annotate, and appropriate mass media products for their own purposes and uses" (9–10). We must also note that fans reedit not only film and television texts but an increasing variety of media formats (note 2).

[2.2] In addition to reediting feature films, fan editors typically design supplemental material such as DVD or Blu-ray box art, posters, and promotional trailers. Increasing numbers of contemporary fan edits are based on Blu-ray sources and include multichannel sound mixes as well as the fans' own audio commentaries. In online forums, collectors of fan edits say they shelve the edits next to the original versions of films. Thus there is a degree of parity among Hollywood's original products, their sanctioned revisions, and fan edits of them. Some fan edits, like The Crow: City of Angels—Second Coming (DCP, 2007), Legion: An Exorcist III Fanedit (spicediver, 2011), and The Dark Crystal: Director's Cut (Christopher Orgeron, 2013), aim to restore (or approximate) the original director's creative vision; in this, they are similar to official restorations such as Superman II—The Richard Donner Cut (Michael Thau, 2006) and Mr. Arkadin—The Comprehensive Version (Stefan Drössler and Claude Berteme, 2006). However, the creators of commercial reedits and restorations often benefit from access to original production elements, such as film negatives, and to professionally restored sound recordings, and occasionally the original director participates in the restoration. On the other hand, most fan edits are produced by independents using home video releases with fully mixed audio and visual elements that must be reverse-engineered in order to reconfigure the content (note 3). In most cases, fan edits are not attempts at restoration but completely alternative versions.

Wolf Dancer (by CBB) - Audio Editing Demonstration from Joshua Wille on Vimeo.

Video 1. Video demonstrating the extensive audio editing involved in a scene from CBB's Wolf Dancer (2010), which is a fan edit based on Dances with Wolves (1990). CBB removed Kevin Costner's voice-over narration and reconstructed all of the sound effects in the scene.

WATCHMEN: MIDNIGHT - Fanedit Color Correction Demonstration 1 from Joshua Wille on Vimeo.

Video 2. Split-screen video comparing the color grading work in select scenes from Flixcapacitor's Watchmen: Midnight (2011) and the original film versions of Watchmen (2009). Flixcapacitor reduced the blue tint present in the original film in order to produce natural skin tones and reveal details about the set production designs that were inspired by the original comic book color palette.

[2.3] Scholars, critics, and journalists have often characterized fan edits as the work of disgruntled fans seeking to redeem the work of indifferent Hollywood magnates such as George Lucas (Lauten 2001; DeLarge 2001; Gates 2001; Knight 2001; Mason 2008, 86–87; Tryon 2012, 181). Fan edits are described as a means for insatiable fans to "express their displeasure" (Weinberg Nokes 2004, 615) with films by removing "what they perceive to be dead weight" (Young 2008, 259). Phillips (2012) argues that fan edits are efforts to reclaim Hollywood films and are structurally unlike "other forms of fan creation, which embrace their marginality to enable greater creativity" (3.2). However, when several Fanedit.org (http://www.fanedit.org) administrators hosted an interactive panel at the May 2013 BlasterCon science fiction convention in Los Angeles, they explained that fan editors are motivated by the desire to explore narratives and forms, not just to fix or reclaim Hollywood films. They screened several excerpts from edits made in various styles and emphasized that the true goal of fan editing is to artistically reconfigure media. One panelist, L8wrtr, explained,

[2.4] Fan editing uses nonlinear editing software to rearrange, modify, and integrate existing media in new and different ways. That's the technical side of it, that's just ones and zeroes. But the thing that really makes fan editing what it is, is that there's an artistic vision to the process of what you're trying to do. You actually have an end goal. It's not just cutting out things that offended you in the film, it's about trying to make something new that didn't exist before.

[2.5] Contemporary fan edits take various forms, either modifying an existing narrative, blending two or more narratives, or forging something completely unexpected. Consider the idiosyncratic work of the fan editor called %20 (pronounced "none"; "%20" is the HTML code for a blank space), whose Thee Backslacpking with Media (2009) and AARRSSTW-WTSSRRAA (2013) intentionally "provide little to zero entertainment value, viewer reward, societal insight, or benefit" (http://noneinc.com/AARRSSTW-WTSSRRAA/AARRSSTW-WTSSRRAA-20121227.html). Other fan editors create kinetic assemblages and meditative tone poems, such as Blueyoda's (fe) la vie (2009), or aesthetically transform mainstream films to reflect cult genres, as do The Man Behind The Mask's Jaws: The Sharksploitation Edit (2009) and Neglify's Scream—The Giallo Cut (2012).

Memories Alone Preview from Q2 Faneditor on Vimeo.

Video 3. Trailer for Q2's Memories Alone (2013), a feature-length fan edit that combines the parallel narratives in The Wrestler (2008) and Black Swan (2010) into one film about an estranged father and daughter. To some degree, this fan edit reflects an unachieved goal of director Darren Aronofsky, who considers Black Swan to be a companion to The Wrestler and had hoped that cinemas would screen the films together (Associated Press 2010).

[2.6] Phillips (2012) observes that fan editors achieve a degree of creative control over their work that is comparable to that of an auteur, but he is wrong when he suggests that fan editors perceive their work as "director's cuts" (2.1). Like journalists such as Wortham (2008), he misconstrues the intentions of fan editors. Instead of treating their works as definitive versions, as the term "director's cut" implies, fan editors embrace the diversity of their efforts. They build on the revisionist works of others and often cite other fan edits as inspirations. For example, in introducing his trilogy of Star Wars prequel fan edits, L8wrtr (2010a) recalls,

[2.7] With Nichols choosing to never release an edit of Episode III I began playing around with the idea of editing it myself…Technical/quality issues with my early drafts led me to fanedit.org where I found the expertise and assistance needed to resolve the challenges I was facing.

[2.8] By that time however I'd come to understand just how much could be achieved with fanediting. No longer could I be satisfied [with] Mike Nichols' releases. I realized that these movies could be cut deeper, that more nuance could be applied within scenes to change tone and improve dialog, which improves character and audience reaction.

[2.9] Without a conscientious study of contemporary fan edits, it can be difficult to define fan editing in the context of other fan works. Barr (2014) explains that fan edits, as transformative narratives, should be recognized under the broad definition of fan fiction. However, like Weinberg Nokes (2004, 615) and Young (2008, 259), Barr labels fan edits a type of fan film instead of examining what makes them distinct. Tryon (2012, 182) characterizes fan vids by their use of juxtaposition and montage but disregards the fact that many fan edits use the same techniques. Phillips (2012), situating fan edits between fan vids and fan films, stipulates that fan edits "only use existing material, while fan films produce new content" (2.4). It is true that fan edits are mostly composed of repurposed material, but there are notable exceptions, such as the original video content produced for Adywan's Star Wars: Revisited (2008—), a particularly popular series of fan edits. For his forthcoming version of Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1979), Adywan has assembled an international crew of volunteer filmmakers to help with casting, costuming, and shooting new digital video to be incorporated in the film.

Figure 1. On the third unit set in Montreal, Quebec, an actor in full Darth Vader costume holds a film slate for the production of new footage in Adywan's Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back Revisited. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

Figure 2. In California, Adywan's second unit director works with actors dressed in rebel soldier uniforms on a backyard green screen stage. The second unit prepared new material for the Battle of Hoth to be incorporated into Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back Revisited. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

Figure 3. In his UK workshop, Adywan crafted miniature trees for new shots of swamps on planet Dagobah in Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back Revisited. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

Figure 4. Also under construction in Adywan's UK workshop is a canyon miniature set that measures 13 feet. It will be used in capturing new video material for Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back Revisited. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

[2.10] In many ways, Adywan's work exemplifies the creative spirit behind many fan edits. It begins with curiosity and is enabled by contemporary technology. His first project (2008), based on Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977), was originally conceived as a color correction experiment. Adywan began to tinker with other visual effects, and eventually he completed an extensive fan edit that revised nearly every shot in the film. Like many fan editors, Adywan explains that he was inspired to reedit films by watching earlier Star Wars fan edits (Mollo 2009), while doubleofive (2010) equates the fan editor's creative impulse with that of George Lucas in his revisionist filmmaking mode, observing, "Adywan isn't making the Special Edition Lucas should have made, he's making the version Young Adywan saw in theaters, using his modern skills to fill in where his imagination had to back in 1980."

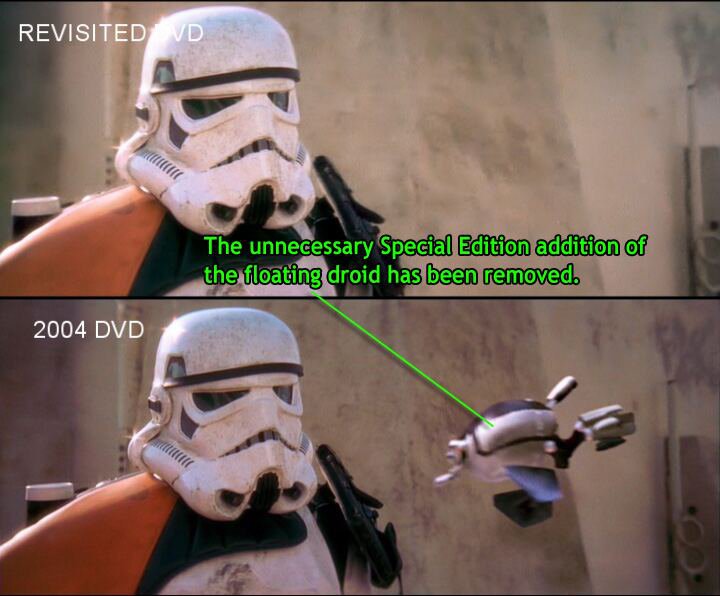

Figure 5. Split-screen image reveals that a probe droid, which was added to a shot of a storm trooper on planet Tatooine in the Star Wars Special Edition, has been erased in Adywan's Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope Revisited. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

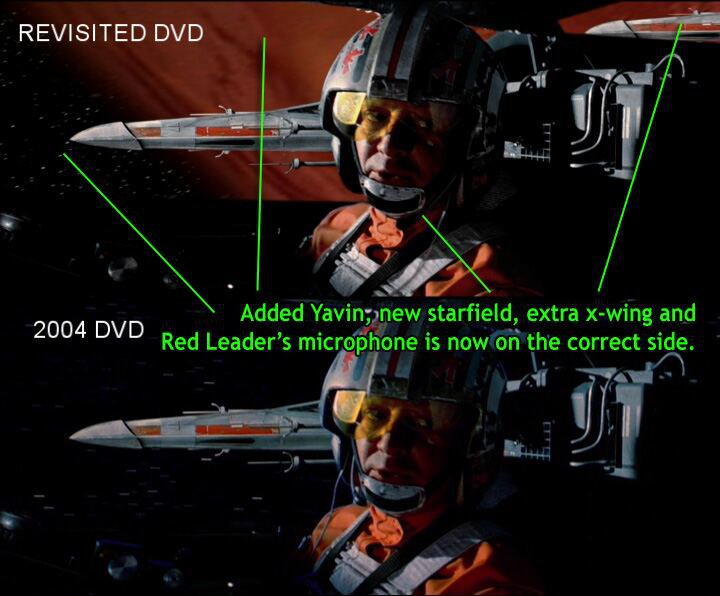

Figure 6. Split-screen image compares two versions of a shot of a rebel pilot in his X-Wing cockpit during the Battle of Yavin. For his fan edit, Adywan digitally replaced the star field, added the massive planet Yavin to the background, and moved the pilot's microphone to the opposite side of his helmet. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

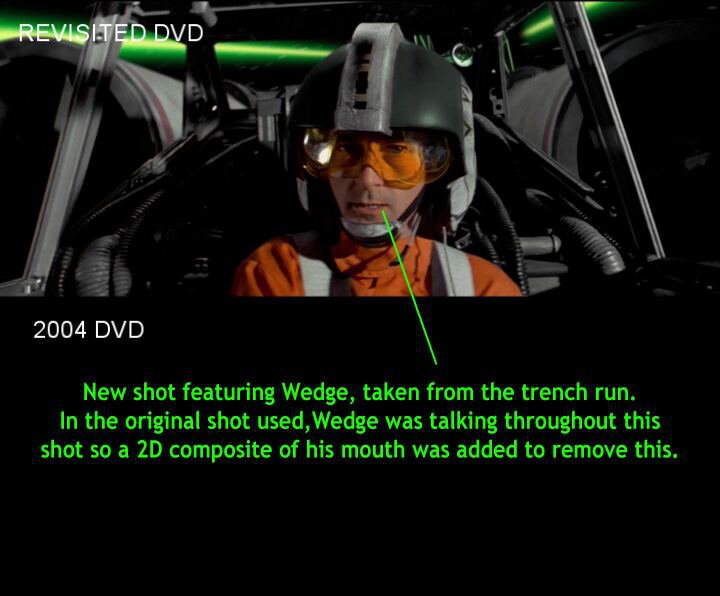

Figure 7. Adywan created a new shot of rebel pilot Wedge Antilles by reusing a close-up of the character talking during the trench run on the Death Star. Adywan performed a 2-D composite over Wedge's mouth to make him appear as though he was not speaking. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

Figure 8. Split-screen image compares two versions of shot featuring Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and Chewbacca standing before Princess Leia at the conclusion of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. In the original version, only Luke and Han received medals from Leia. In his fan edit, Adywan digitally added a medal around Chewbacca's neck. Photo by Adywan. [View larger image.]

3. The Phantom Edit: From hype to prototype

[3.1] The first public record of The Phantom Edit is Erin Lauten's May 17, 2001, blurb on the professional film editing news Web site Editorsnet.com (Mike J. Nichols, e-mail to author). Lauten wrote, "A mysterious video cassette containing a re-edited version of George Lucas' 'Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace' has started circulating around Hollywood. Called 'Star Wars Episode I.I: The Phantom Edit,' the 'special corrector's edition' challenges the vision of the original film." Lauten characterized The Phantom Edit as a challenge to George Lucas, but Nichols explained that it was merely an editing exercise and he was actually inspired by early revisionary work by Lucas, who supposedly reedited workprints of Hollywood films in order to show directors how they could be improved (Hodgetts 2007). Nichols (2001b) argues that by the time Lucas produced Episode I, the Star Wars creator had become artistically insulated by wealth and a crew of obsequious employees at Lucasfilm who were afraid to question his creative decisions. Nichols maintains that his loftiest goal in making The Phantom Edit was not to threaten Lucas's authority or earn money, but to engage Lucas in a creative conversation. "I don't think I ruined his story," he said in a September 7, 2001, interview with Daniel Greenberg for the Washington Post. "It's the same story he was trying to tell, just told more effectively—as if I worked for him." In 2013, to reaffirm that he was inspired by the same principles of storytelling and editing once advocated by Lucas, as well as to clarify his intention in making The Phantom Edit, Nichols posted to YouTube a compilation of interviews with Lucasfilm employees, taken from the DVD of his second fan edit, Attack of the Phantom (2002) (video 4).

Video 4. Attack of the Phantom (2002), a fan edit by Mike J. Nichols. In the video's description, Nichols explained, "Many people think The Phantom Edit was about cutting out parts of a movie you don't like (Jar Jar Binks for example) but that wasn't the point or the message…Here the new interview order now hauntingly serves as a aftermath commentary in [the Lucasfilm employees'] own words as to why The Phantom Menace became such a failure."

[3.2] Soon after The Phantom Edit went public, a second edit of Episode I appeared, entitled The Phantom Re-edit, and other similarly titled works have appeared since. Although they were created by different fan editors, they are often confused and misrepresented. For example, Nichols attempted to minimize the screen time devoted to Jar Jar Binks in The Phantom Edit without disrupting the story, but subsequent accounts (Williams 2005, 163; Mason 2008; Schaller 2009) have incorrectly reported that he removed Jar Jar Binks entirely from the film. Rather than omitting the character, the unidentified trio of editors behind The Phantom Re-edit digitally scrambled Jar Jar Binks's voice and wrote new subtitled dialogue in an attempt to represent him as a wise native of the planet Naboo (Rikter 2004; McDermott 2006, 254). Fans and journalists nicknamed The Phantom Edit the West Coast or LA version, since that was where Nichols lived, and called The Phantom Re-edit the East Coast or New York version, because two of its creators were rumored to live there (Griffin 2001a; Rikter 2004). Another independently created Episode I fan edit from that period, The Phantom's New Hope, has been attributed to Andrew Pagana and includes variations of the edits found in both The Phantom Edit and The Phantom Re-edit (Rikter 2004; White 2010, 305–6). Judging from a June 7, 2001, article by Andrew Rodgers (2001c), The Phantom Re-edit was likely the first version to be shared with George Lucas; "worried that other amateur filmmakers would be flooding Lucasfilm offices with their own re-edited versions or lower-quality copies of his own, The Phantom Editor then made arrangements to get Lucas an authentic copy of his re-edit."

[3.3] As The Phantom Edit circulated on videotape and eventually made its way onto the Internet, filmmaker Kevin Smith, an outspoken Star Wars fan who is rumored to recut Hollywood films for his own consumption, was briefly suspected of being The Phantom Editor (Rikter 2004) (note 4). On May 31, 2001, Andrew Rodgers (2001i) published the first in a series of articles on Zap2it (http://www.zap2it.com/) devoted to the content, controversy, and cultural appeal of The Phantom Edit. Rodgers's first post repeated speculations that Smith might be its creator, and on June 4 Rodgers (2001f) provided a detailed report on The Phantom Edit, noting the major changes it made to Episode I and reprinting Nichols's disclaimer, which replaced the iconic Star Wars opening text crawl:

[3.4] Anticipating the arrival of the newest Star Wars film, some fans, like myself, were extremely disappointed by the finished product. So being someone of the "George Lucas Generation," I have re-edited a standard VHS version of "The Phantom Menace," into what I believe is a much stronger film by relieving the viewer [of] as much story redundancy, pointless Anakin actions and dialogue, and Jar Jar Binks, as possible.

[3.5] During that early period, Lucas and company were aware of The Phantom Edit and expressed support for it. Rodgers (2001f) also revealed that, when questioned about The Phantom Edit backstage at the 2001 MTV Movie Awards ceremony, Lucas replied, "The Internet is a new medium, it's all about doing things like that. I haven't seen it. I would like to." Rodgers reported that Jeanne Cole, a spokesperson for Lucasfilm, explained that the company welcomed fan participation in the Star Wars franchise "as long as nobody crosses that line—either in bad taste or in profiting from the use of our characters," adding, "At the end of the day this is about everybody just having fun with Star Wars. Go be creative." But despite these signs of approval from Lucas, the next day Rodgers (2001e) suggested that The Phantom Edit might violate copyright. He speculated that Lucas might choose not to bring suit because doing so could upset a zealous fan base.

[3.6] On June 6, Rodgers (2001a) published portions of an interview he had conducted with The Phantom Editor via e-mail. Nichols was wary of disclosing his real name and location and expressed cynicism about the entertainment industry. "I'll say this," he wrote; "I am in a town where many potential projects gone wrong will lose millions of studio dollars while my demo and resume sit neatly unopened on the desk of someone making lunch plans." Nichols also said that it took him many months to reedit Lucas's film, and that it was challenging to reedit mixed sound and picture. "Had I Lucas's original elements to work with," he added, "I could promise an even better final product." Nichols claimed that The Phantom Editor was receiving hundreds of e-mails daily from around the world, and he seemed interested in stirring public interest in the neglected role of a film editor. "The industry doesn't paint an important portrait of editing or editors," he argued. "Editing isn't on the tip of anyone's tongue at Hollywood parties. At least it wasn't until now."

[3.7] In articles published on June 10, 11, and 14, Rodgers (2001g, 2001b, 2001d) reported that a newly assembled grassroots group, the Phantom Edit Fan Network, was distributing videotape copies of the fan edit on Hollywood Boulevard and shipping them to other states and foreign countries in order to encourage further distribution. By that time, Lucas and company had changed their position on fan edits. On June 14, Rodgers (2001d) quoted Jeanne Cole:

[3.8] "I think what we've come to realize is that when we first heard about the [reedits], we realized that these were fans that were having some fun with Star Wars, which we've never had a problem with. But over the last 10 days, this thing has grown and it's taken on a life of its own—as things do sometimes when associated with Star Wars," Cole said.

[3.9] "And, when we started hearing about massive duplication and distribution, we realized then that we had to be very clear that duplication and distribution of our materials is an infringement," Cole added…"The whole bottom line is, Star Wars exists because of its fans," she said. "We don't want to anger them. We want them to have fun with it. But then we have to be really clear, too, about how far you can have fun with it."

[3.10] As The Phantom Edit became more widely known, criticism of it intensified. As Rodgers was reporting on its creative merits, a series of derisive editorials appeared on Rebel Rouser, a subsidiary of a Star Wars fan Web site, TheForce.net (http://theforce.net/). In a June 12, 2001, review, "The Phantom Edit—An Edit Too Far," Alexander DeLarge said that it was "alarming to see how when a big studio re-cuts a movie to pieces to fulfil his expectations, fanboys shout [at George Lucas] in disgust. But when a fanboy does the same thing, he is applauded and cheered, because 'he's sticking it to the man'…I think all the Phantom Editor wants is to please himself and the average fanboy." DeLarge defended Lucas's original Episode I and chastised fans who supported "the mutilation of Lucas' vision," concluding, "How quickly have you turned into the Empire, my friends." In "The Phantom Edit—Disrespecting Art" on the following day, Sean Gates (2001) complained that "Star Wars is made to be enjoyed, not dissected like a dead frog in a pan…Why has it become such a complex issue to enjoy a movie?" On June 14, Chris Knight (2001) admitted in "The Phantom Edit—Artistic Rape" that he had not actually watched The Phantom Edit but argued that the purpose of art is to "convey the thoughts of the artist, not what other people want the thoughts of the artist to be…Film shouldn't be treated like a 'choose your own adventure' artform." Knight attempted to shame fans out of reediting films, concluding that "re-editing of Episode I is tantamount to hijacking another's vision, if not outright artistic rape."

[3.11] Knight's rejection of fan edits was a response to Joshua Griffin's June 11 review of The Phantom Re-edit on the same Web site (2001b). Observing their potential to transform narrative, Griffin compared fan edits to the participatory reading in Choose Your Own Adventure youth novels and suggested that "fan versions of [Lucas's] films are breaking new ground, sending a message to the Lucasfilm world what many fans have been saying all along." Griffin followed with a review of Nichols's The Phantom Edit on June 18 (2001a), and although he complimented some of the work, he was careful to avoid suggesting that The Phantom Edit reflected the director's ideas. Instead, Griffin concluded, "This is by no means Lucas's definitive vision. We saw that in the theater in May of 1999."

[3.12] Increasing hype surrounding The Phantom Edit attracted critics from the mainstream, including J. Hoberman (2001) and Michael Wilmington (2001). In his June 18 review of The Phantom Edit, Wilmington compared aspects of the original film to the fan edit, and although he disagreed with fans who claimed that The Phantom Edit was superior to Lucas's original Episode I, he praised the work. "We need good editors," Wilmington wrote, "and even occasionally Phantom ones."

[3.13] Distribution of The Phantom Edit continued despite threats of litigation from Lucasfilm in the press, and Nichols (2001a) writes that on June 26 he was interviewed on camera by Access Hollywood for a segment that was slated to air the following evening. He agreed to the interview on advice from his lawyer, who recommended identifying himself, "name and image, as the guy behind The Phantom Edit," because "Lucasfilm would have less interest in making my life hell…if I was a public figure." To Nichols's dismay, the interviewer pressed him about whether he had profited from bootlegs of The Phantom Edit; he denied that he was responsible for any unlawful distribution. The following evening, Access Hollywood ran promotional spots for the interview, but it never aired. Instead, the segment about The Phantom Edit was replaced by promotional footage for Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005) provided by Lucasfilm. Nichols suspected Access Hollywood had manipulated him in order to bargain with Lucas for exclusive material from the upcoming film, and he recalled that upon leaving the television studio the previous day he had not been asked to sign a release form. "It appeared they were never going to run [the interview]," he wrote. "In retrospect, I imagine they knew that the day I came in to tape it…I was used like a last minute prom date. A bartering chip with Lucasfilm."

The Phantom Interview from Joshua Wille on Vimeo.

Video 5. In response to revived interest in The Phantom Edit on the Internet in November 2013, Nichols produced this compilation of the Access Hollywood teaser footage for his lost interview.

[3.14] On June 28, 2001, Andrew Rodgers (2001h) reprinted an open apology that Nichols, writing as The Phantom Editor, had e-mailed to Zap2it. In the message, he emphasized he had not participated in bootlegging The Phantom Edit and he urged fans to respect the wishes of Lucasfilm by ceasing any underground sales of his edit. He added, "I can now understand first hand the issues that Hollywood and the music industry face in trying to maintain control over the distribution of their content. I sincerely apologize to George Lucas, Lucasfilm Ltd. and the loyal Star Wars fans around the world for my well-intentioned editing demonstration that escalated out of my control."

[3.15] In a September 7, 2001, article in the Washington Post, Daniel Greenberg reported that Mike J. Nichols had finally come forward as The Phantom Editor. By that time, with much of the initial controversy having subsided, critics were able to reflect on some of the implications of The Phantom Edit. In his review for Salon on November 5, 2001, Daniel Kraus suggested that "more than anything, 'The Phantom Edit' magnifies problems [in Episode I] that can't be fixed with clever editing." Kraus added that "until the 'Phantom Edit' controversy, the role of the editor has rarely been appreciated by the public. And in a way, 'The Phantom Edit' illustrates that editors are not automatons serving a dictatorial director, but artists in their own right, contributing as much to a finished film as a writer or cinematographer." Further, Kraus drew parallels between the fan editor and George Lucas, arguing that "the only difference between 'The Phantom Edit' and what Lucas did with his rereleased 'Special Editions' is permission," and "whereas digital technology equals 'boundless imagination' for Lucas, it equals 'cheap accessibility' for everyone else." Charles C. Mann observed in his November 22, 2001, article for PBS Frontline that "Lucas was, in a way, a perfect target…Cheaper and better in every aspect, the new technology, Lucas has long maintained, will empower a new generation of cinematic artists and entertainers." Thus, the digital technology pioneered by Lucas had become a way for fans to shift a balance of creative power. However, Nichols saw himself as an unlikely challenger to Lucas's multimillion dollar filmmaking operation. In a blog post on August 22, 2001, he wrote, "I am one guy in a one-bedroom apartment with Final Cut Pro, 128 (impossible!) megabytes of ram on a bottom line Macintosh computer resting on an unsteady $40 computer desk, and George Lucas is threatened by me?"

[3.16] The question of threat was central to Richard Fausset's June 1, 2002, profile of Nichols for the Los Angeles Times. "This messy Burbank living room," Fausset wrote, "with its cheap computer and jury-rigged video station, may be the most notorious rebel outpost in the 'Star Wars' universe this side of the ice planet Hoth. It is the lair of the Phantom Editor…The thirtysomething film editor…knows he sounds as brash as the teenage Anakin Skywalker when he says, 'I have the storytelling sense that George Lucas once had and lost.'" Reflecting on the implications of fan editing for artistic authority, Fausset approached David Madden, an executive vice president at Fox Television Studios, who had viewed The Phantom Edit. "I don't mean to sound too 20th century," said Madden, "but I come from this tradition where an artist works really hard to create a vision. I'm a little scared, because [fan reedits] somehow take away the primitive power of me telling you a story, and you having to follow the story."

[3.17] Speaking to Fausset, Nichols described fan editing as a form of "proactive criticism," arguing that "now, big-time directors know that if they do a [bad] job, somebody may redo it and make them look like idiots." Kraus (2001) observed, "The shifting of power from the filmmakers to the fans is both disturbing and exciting. It is disturbing because there will no longer be any sort of quality control, aside from the natural assumption that the best 'fan edits' will be the ones that get passed around the most…In the upcoming years we will be privileged to witness, essentially, critics making movies, which we haven't seen in abundance since French New Wavers like Godard and Truffaut decided that the best response to a film was making another film." Also seeing fan edits as challenges to original filmmakers, in his July 15, 2001, article for the New York Times, J. Hoberman posited The Phantom Edit as a democratic counterweight to monolithic filmmakers such as George Lucas. "Prometheus-like," Hoberman wrote, "'The Phantom Edit' strikes back against the tyranny of the artist who has successfully colonized the imagination of millions." Although the Phantom Editor was characterized as a creative crusader, Nichols expressed little regard for other fan edits of Episode I or the burgeoning fan editing communities. Faussett (2002) noted that "Nichols became as testy as any auteur when talk turned to copycat phantom edits that have traded on his reputation. 'Yeah,' he snorts, 'Attack of the clones.'"

[3.18] In 2002, The Phantom Editor released Attack of the Phantom, a revision of Episode II that did not generate the same degree of mainstream discourse as The Phantom Edit but has been called a stronger work (Duff 2007; Darthmojo 2008). Instead of going on to release a version of Episode III, Nichols chose to retire from fan editing and focus on his career as an editor and postproduction producer for film and television, including the later seasons of HBO's Sex in the City (1998–2004), which he deftly reedited for syndication (Hodgetts 2007). Why Nichols quit fan editing has not been confirmed, but Boon23 (2009b), the first Webmaster of Fanedit.org, submits that after the release of Attack of the Phantom, George Lucas summoned Nichols to his Skywalker Ranch and convinced him not to revise Episode III. Alternatively, L8wrtr (2010b) claims that Nichols began work on an Episode III edit but eventually lost interest in the project.

[3.19] In spite of the aforementioned interpretations of The Phantom Edit as a groundbreaking or contentious effort and The Phantom Editor as a creative revolutionary, a pirate, or a disgruntled fan, Nichols maintains that his original intentions were less sensational. He explains that The Phantom Edit was simply an editing exercise created "just for the audience of me," and "no one knew who I was and it was to always remain that way" (Nichols 2014, e-mail to author). Although Nichols is often credited with bringing the most public attention to fan editing and he has engaged in some playful discourse regarding his work, he is disassociated with contemporary fan editors.

4. Fan editing communities versus copyright culture

[4.1] The Phantom Edit remains a source of inspiration for newcomers to fan editing as well as a talking point for Star Wars fans. In May 2002, Jason "Jay" Sylvester founded OriginalTrilogy.com, a Star Wars forum dedicated to the appreciation of the classic Star Wars films and to promoting their unmodified versions, colloquially known as "George's Original Unaltered Trilogy," or "The G.O.U.T." OriginalTrilogy.com became one of the first centralized sites for fans to share their experiences with The Phantom Edit. Star Wars–related transformative discourse continued to dominate on OriginalTrilogy.com but fan edits and preservations of other science fiction, fantasy, and adventure films also surfaced in its forums.

[4.2] Boon23 founded Fanedit.org in January 2007, in order to cater to expanding interests in fan editing (The Man Behind The Mask 2010), and the Web site quickly developed into the most comprehensive resource for fan editors. The popularity of Fanedit.org is due to its lively forums where fan editors collaborate and critique their works, its extensive Internet Fanedit Database (http://fanedit.org/ifdb), and its former role of providing access to fan edits.

[4.3] Meticulously cataloged on Fanedit.org, numerous fan edits were once available through BitTorrent trackers and direct downloads from popular file-hosting Web sites such as RapidShare.com and Megaupload.com. However, in November 2008 the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), issued a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) notice against Fanedit.org for copyright infringement. In order to prevent its Web host from closing the site, Fanedit.org removed all download links (Enigmax 2008). The MPAA's action surprised Boon23. The year before, Lucasfilm had contacted him with a polite request to remove one fan edit from the site. According to Boon23, Lucasfilm made no other complaint about the online repository, which contained at least eighty Star Wars fan edits (Enigmax 2008). On the basis of this implicit nod of approval from Lucasfilm, Boon23 and the members of Fanedit.org believed that fan editing might rest peacefully in a "gray area" between piracy and the law (Duff 2007; Gaith 2009).

[4.4] In 2008 and 2009, Boon23 took further precautions to ensure Fanedit.org's security and avoid copyright challenges from the MPAA. A German citizen himself, he moved the site to a Web host outside the United States and forbade forum members to say where to obtain fan edits in publicly accessible message threads (Boon23 2009a). However, the burden of support work eventually compelled Boon23 to step down and a new group volunteered to administer the site.

[4.5] Peace was disrupted again on January 19, 2012, when the United States Department of Justice seized Megaupload.com as part of an antipiracy operation. Kim Dotcom's controversial service was a popular choice among fan editors looking for a site to host their work, but the deactivation of Megaupload.com also severed links to hundreds of fan edits. More recently, fan editors have discovered alternative file-hosting sites and distribution methods, but the turbulent arena of copyright regulation on the Internet continues to threaten access to these transformative works.

[4.6] Fan editing is similar to music remixing, which began as an underground practice, eventually gained mainstream acceptance, and was appropriated by the industry. However, fan edits remain marginalized by their questionable legality. When it first appeared, The Phantom Edit was frequently disparaged on the basis of reports of unlawful sales, which raised questions of copyright infringement. Thus, many of the early discussions of fan edits were focused on legal and ethical concerns rather than on the works' creative qualities. Ten years before he retired from Star Wars, George Lucas explained, "Well, everybody wants to be a filmmaker. Part of what I was hoping for with making movies in the first place was to inspire people to be creative. The Phantom Edit was fine as long as they didn't start selling it. Once they started selling it, it became a piracy issue" (Smith 2002, 32).

[4.7] Lucasfilm may have ceased its legal threats once bootlegging of The Phantom Edit reportedly ended and The Phantom Editor retired, but Boon23 and the subsequent administrators of Fanedit.org anticipated their work might be challenged on copyright grounds. Therefore, the fan editing communities stand firmly against piracy and insist their works are noncommercial, experimental projects. Attempting to invoke the fair use provisions in the US Copyright Act of 1976 that allow duplication of copyrighted works for certain noncommercial personal uses, Fanedit.org mandates that participants must own a commercial version of a film before producing or watching a fan edit based on it. Its argument is that a fan edit qualifies as a legally sanctioned duplication rather than a pirated work, but this argument remains untested in the courts. In recent years, however, fan editors have benefited from the efforts of the Organization of Transformative Works to obtain legal exemptions under the DMCA for transformative practices.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] Although previous interpretations of fan edits depict them as narrowly focused attempts by peevish fans to "fix" Hollywood's versions of their beloved stories, a more conscientious survey of the extant work reveals that fan editors are actually experimental filmmakers and digital artists working in a revisionist mode, much like music remixers. Like other forms of remix, fan edits have an inherent reactive component, but they should be recognized primarily for their creative qualities and as contributions to an emerging culture of fluid media. The controversial story of The Phantom Edit that I reconstruct here offers some explanation for the formative scholarly perspectives on fan editing, which have been based largely on inconsistent reports about The Phantom Edit and often are not representative of the actual fan editing subculture. Fan editing practice has advanced since the first appearance of The Phantom Edit and therefore new discussions about fan edits should look to the expanding body of works rather than one seminal piece. Contemporary fan editing, like other collaborative practices that remix media and employ controversial systems of online distribution, remains caught between the spheres of creative expression, commerce, and the law. In keeping with Lawrence Lessig's characterization of the digital era as a return to a read/write creative paradigm of reciprocal production and reproduction, the fan edit joins other forms of remix that increasingly signal that new media artists utilize technology that was once exclusive to the industry. Together, the commercialization of film revisions sanctioned by Hollywood and the existence of fan edits may contribute to an evolving public understanding that cinematic forms are fluid and malleable rather than immutable. Thus the collective work may eventually prove George Lucas's claim that "films never get finished, they get abandoned."

[5.2] Further research into fan editing could explore its practical techniques, its social organization, and its position in the changing tide of intellectual property discourse. For example, studies might examine the use of fan editing as a form of practical film and television criticism or further delineate the various fan editing genres and discuss their formal relationship to the sanctioned revisionist work of film preservationists. Fan editor demographics have not been established and should be discussed in the context of other fan labor, and although most fan edits are consumed in private homes, further research could explore the reception and legal implications of their public screenings (e.g., spicediver's Legion: An Exorcist III Fanedit screened at the Mad Monster Party horror convention in Charlotte, North Carolina, on March 25, 2012; Flixcapacitor's Watchmen: Midnight screened at StarFest in Denver, Colorado, on April 19, 2013; and screenings of Q2's Northwest Passage: A Twin Peaks Fanedit were hosted by the Paley Center for Media in Los Angeles and New York City on March 29, 2014) (note 5). Furthermore, using the economy of music remixes as the basis for inquiry, research should address the potential for fan edits to be appropriated and commodified by the media industries.

6. Acknowledgments

[6.1] I wish to express thanks to the administrators and members of Fanedit.org, especially L8wrtr, Neglify, Reave, and Blueyoda, for discussions about their craft, and to The Man Behind The Mask, Mollo, and Gaith for writing previous histories of fan editing. Finally, I would like to thank Kevin Brownlow and Mike J. Nichols for being invaluable resources during my research.