1. Introduction

[1.1] From 2006 to 2010, Excalibur Comics in Portland, Oregon, hosted Wonder Woman Day, an annual charity event that, in its five years, raised over $100,000 for local nonprofit organizations serving victims of domestic violence. Conceived and organized by Portland-based writer Andy Mangels, Wonder Woman Day confirms the utility of mass culture and of the arena of public consumption for civic engagement. Most importantly, Wonder Woman Day is an ideal vehicle by which fans participate in the circulation of affect as a form of capital, collapsing the boundaries of citizen and consumer. Wonder Woman's ethos of "loving submission" symbolically embodies the conflation of affect and agency determined by participation in a collective utopian fantasy. Wonder Woman Day allows fans to recirculate this affective agency, confirming what Sara Ahmed calls the "very public nature of emotions" and "the emotive nature of publics" (2004, 14). Wonder Woman Day indicates that emotion gains in both emotive and commodity power the more it is circulated; thus this charitable event mirrors the affective power of mass culture texts beloved by fans. Central to this circulation is the figure of Wonder Woman as a conduit for compassion that critiques hegemony. Fans' compassion for domestic violence victims informs a utopian desire to change social norms that is authorized by Wonder Woman. Affect is thus a guiding agent in the process of moral regeneration, symbolically linking fans to a comparable impulse felt by superheroes. That fans do this through the figure of Wonder Woman, the ideal utopian female superhero, realizes Lauren Berlant's observation that "to feel compassion…is at best to take the first step toward forging a personal relation to a politics of the practice of equality" (2004, 9). Further, Wonder Woman Day confirms Spinoza's assertion (2000, 164) that emotions circulate between bodies and determine what those bodies are capable of. Importantly, then, Wonder Woman Day bonds the consumer-citizen to absent, yet present bodies: those of domestic violence victims and that of Wonder Woman. In doing so, it sustains an affective circuit of reciprocal meaning among all three, cementing the link between public and private, affect and agency.

[1.2] Wonder Woman was the creation of Dr. William Moulton Marston, a Harvard-educated psychiatrist who, under the pen name Charles Moulton, conceived of a female superhero who, in his words, was

[1.3] psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world. There isn't love enough in the male organism to run this planet peacefully. Woman's body contains twice as many love generating organs and endocrine mechanisms as the male. What woman lacks is the dominance or self assertive power to put over and enforce her love desires. I have given Wonder Woman this dominant force but have kept her loving, tender, maternal and feminine in every other way. (Daniels 2000, 22–23)

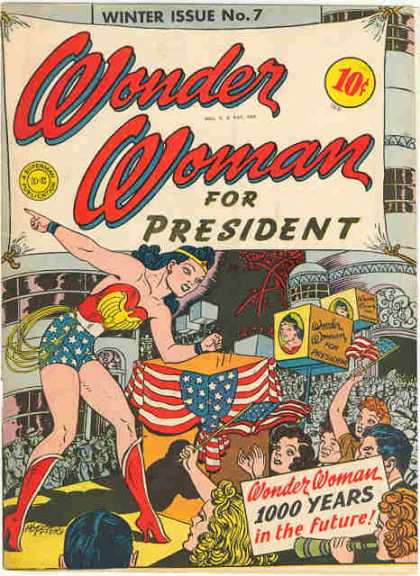

[1.4] Debuting in All Star Comics no. 8 (cover dated Dec. 1941–Jan. 1942), Wonder Woman was unique among the nascent army of superheroes in that she was conceived in these expressly politically utopian terms. Like most superheroes of this period, she was recruited for the war effort, and her gendered utopian vision was instantly conflated with a comparable utopian mission for America. While in her first appearance America is described as "the last citadel of democracy, and of equal rights for women," this is clearly a utopian ideal that the nation falls short of fulfilling. This failure is confirmed by the very presence of a Wonder Woman: her essential difference from non-superheroic American women is a reminder of the need for not simply gender parity but, according to Marston, female hegemony. In a November 11, 1937, article in the New York Times, Marston said that "the next one hundred years will see the beginning of an American matriarchy—a nation of Amazons in the psychological rather than physical sense" (Daniels 2000, 19). Yet his own utopian vision is frequently betrayed by the politics of the time and the conservative nature of World War II mass culture. For example, the cover of Wonder Woman no. 7 (winter 1943) (figure 1) features the words "For President" below the masthead and shows Wonder Woman stumping on the campaign trail, accompanied by the text "Wonder Woman 1000 Years in the Future!" If the readers of Wonder Woman were allowed to imagine Marston's matriarchal utopia, it was a dream circulated through the familiar mechanisms of democratic politics (conflating essential American institutions with this feminist fantasy) and safely deferred to a distant future rendered as mythic as Wonder Woman's Amazonian past.

Figure 1. Wonder Woman campaigns for a utopian dream.[View larger image.]

[1.5] Importantly, the cover image of Wonder Woman as a presidential candidate features both men and women in the cheering crowd, confirming Marston's insistence that his vision of a matriarchal society is aimed at both male and female readers. So is the governing conceit that Wonder Woman exports from Paradise Island and that informs Marston's utopian vision. As Wonder Woman's mother, Queen Hyppolyta, explains in Wonder Woman no. 29 (March–April 1948), "The only real happiness for anybody is to be found in obedience to loving authority." Submission to a loving matriarch provides the affective structure to Marston's articulation of what he termed "women's values," which he wished to mobilize against patriarchal power. This defining political platform has been vital to an understanding of Wonder Woman in the decades following Marston's tenure as her writer (he died in 1947). While many writers for DC Comics have drifted far afield from Marston's conception of the character (typically reducing her to standard male superhero fisticuffs or, in one glaring instance, removing her power altogether), others have recognized her primary appeal as a progressive figure. George Perez, a self-described feminist who wrote Wonder Woman from 1987 to 1992, has said that he primarily considered her "a peace character" (Daniels 2000, 169). As Marc Edward DiPaolo notes, "cultural critics…have asserted that Wonder Woman should ideally promote peace over war, feminism over conservatism, and multiculturalism over American Imperialism" (2007, 152). As Mangels puts it, "When I look at Wonder Woman…I'm seeing a woman that's powerful, a woman with a sense of truth and grace to her. Her message was always about accepting everybody as equals and about making the world a better place" ("World of Wonder").

2. Wonder Woman and me: The bond(age) of affect

[2.1] One of the most significant, and controversial, aspects of Marston's Wonder Woman stories was their emphasis on physical bondage as a trope of the social submission he advocated. Wonder Woman is rendered powerless when tied up or chained by a man (much as she once lost her powers at the hands of a male writer). Wonder Woman is defined by her voluntary submission to the will of her mother and, in order for her utopian social vision to be realized, requires the willing submission of the masses. Significantly, Wonder Woman must also submit to the will of the state, an act she performs through the power of affect. That is, she wholly gives herself over to America's fight for freedom against the Axis in her origin story in large part because she falls in love with Steve Trevor. Marston removes the threat that this defining action might have on Wonder Woman's feminist agency by rendering Trevor essentially impotent. Wonder Woman is never compromised by her love of Trevor, only motivated by it, and it never supersedes her pursuit of freedom and equality for all.

[2.2] Wonder Woman's performance of submission is a model for readers, as it reconciles the essential tension of American identity between the individualism celebrated in American culture and the submission to authority required by the state. Further, fans perform this reconciliation in the process of consuming Wonder Woman texts, as well as participating in Wonder Woman Day, for these activities require the consumer-citizen both to submit to the machinations of mass culture and to engage in the public sphere by advocating social change. The affect that defines this participation allows consumer-citizens to confirm their individual subjectivity and retain a sense of agency within these structures. Importantly, comic book writer-artist Phil Jimenez, who worked on Wonder Woman from 2000 to 2003, modeled this response himself during his tenure on the title. Jimenez confesses that his lifelong attraction to strong female superheroes was largely based on his gay identity: "My favorite characters were almost always women…[such as] Wonder Woman…I believe it's because these women were strong, powerful characters and the objects of desire of men. As a gay teen, that's what I wanted to be" (Kim 2002, 66). Jimenez translated his affective fandom into an affective assertion of his own identity once he was a professional in the comic book industry: "I came out in the back of a comic I wrote and drew as a tribute to my first boyfriend, the man who hired me at DC Comics, Neal Pozner. I got the most incredible response—literally hundreds of pieces of mail from gay readers."

[2.3] This illustrates how fans' utopian desires directly inform their attraction to certain characters and confirms that both Wonder Woman's gender and her antipatriarchal origins make her available for these perpetual progressive readings. According to Cornel Sandvoss, "As fantasies are a simultaneous form of externalization of internal desires and internalization of external texts and images, there is no simple starting or end point of fantasies in a primal scene or in external objects, or in the fan's self" (2005, 79). Since fantasy is produced at the nexus of text and reader, it is not surprising that Mangels turned to Wonder Woman as a means of addressing the issue of domestic violence. Importantly, in doing so, Mangels attempted to duplicate Marston's addressing of both males and females regarding the transcendent power of matriarchal authority. The underlying nostalgia that informs Mangels's use of this character further conflates mass culture with individual subjectivity and experience, for Mangels is inspired not only by Marston's original vision for Wonder Woman but by his own affective childhood memories. In explaining why he decided to launch Wonder Woman Day, Mangels says, "I loved and identified with Wonder Woman since I was a child, both in the comics and the TV show. And I had a strong mother figure who enabled me to be very cognizant of the power of what women could be. I was born in 1966, so this was during the Equal Rights Amendment. This also relates to my gay identity. Wonder Woman represents love and equality for everyone" (pers. comm.). He goes on to note that he chose to use Wonder Woman to promote domestic violence awareness because it is an issue that "affects everyone, but especially women, children, and the disenfranchised," which, he says, allowed him to address the same kinds of social issues that Wonder Woman contends with. He wanted to raise money for domestic violence programs that provide services for both genders, in addition to shelters serving only women, again aligning himself with Marston's utopian vision of gender inclusiveness.

[2.4] Mangels's narrative of his own affective fan and family histories partially mirrors the background of Wonder Woman (who was also strongly influenced by her mother) and explicitly places them within a national historical context of progressive politics. That the Equal Rights Amendment failed to be ratified only confirms the ongoing need to promote a combination of progressive feminist politics and Marston's vision of matriarchal authority for all. Thus Mangels's own utopian expression of Wonder Woman sees all of us, regardless of gender, race, class, and sexuality, as potential Amazons. Yet, while Mangels's utopian project for Wonder Woman Day is gender-inclusive, like the comic books, he cannot escape the gender politics of the everyday. So the broad perception of domestic violence, in line with Marston's conception of Wonder Woman, is that men are the problem. Like Marston, Mangels positions himself as an antinormative, masculine authorizing agent, mitigating the implicit critique of masculinity but still locating social problems primarily within the domain of patriarchy. Mangels also draws parallels between himself and Marston, noting that, like Marston, he lives a nonheteronormative lifestyles (Marston was in a polygamous relationship through most of his adult life). Through the mass culture fantasy text of Wonder Woman, nonnormative subjectivities of consumer and producer are conflated, suggesting that such synthesis is an ideal strategy for social change.

[2.5] Like Marston's, Mangels's utopian vision of American society can accommodate (and, in fact, requires the accommodation of) lifestyles outside of the heteronormative standard, and such lifestyles are authorized through loving submission to matriarchal authority. This is implicit in Mangels's reflections on his personal background and his attraction to Wonder Woman (performing a kind of submission to the authority of the matriarchal commodity icon). Significantly, his utopian social vision as mediated through Wonder Woman is reinforced by sentiments shared by primary contributors to the metatext, further aligning consumer and producer affect. Lynda Carter has said of the character she played on television, "She was never against men, she was just for women." Commenting on the fact that Wonder Woman was never portrayed as a victim, she observes, "I think that's part of the empowerment, and it's also the secret self, the archetype that appeals to gay and lesbian men and women, that there's a secret self that is waiting to be unveiled, that is powerful and won't ever be a victim…I'm such a champion of civil liberties for the gay and lesbian population, like I am for women and being able to choose…Anything that is trying to take away personal freedom is not a very good thing. It's not what the nation is about" (Carter 2009). Tellingly duplicating the condensation of character and actor so often performed by fans, Carter aligns her own political subjectivity with the Wonder Woman ethos, affirming a sense of self and national identity through the blurring of boundaries between fantasy and reality as mediated by the mass culture text. Mangels confirms Carter's observations regarding gay fans and Wonder Woman in an interview with comic book writer-artist and historian Trina Robbins: "The concept of a secret identity is significant to the appeal of super heroes to gay readers…It hides from the world the best attributes of the characters, the thing that makes them different from the norm, but also better" (Robbins 2008, 89). Robbins concludes that Wonder Woman is threatening to heterosexual men for the same reasons she is attractive to gay men: not only is she physically powerful, but she also chooses to use her powers in nonviolent ways. Thus Wonder Woman herself literally and figuratively contains the aggression of patriarchal authority, embodying the utopian ideal that gay fans such as Mangels so strongly identify with. By extension, she also reveals the "secret identity" of America itself: the progressive, utopian possibilities hidden in its very origins.

[2.6] Mangels notes that his Mormon upbringing taught him that "if you take care of your community, it will take care of you" (pers. comm.), yet he turns to mass culture, not the church, to actualize this ethos. Implicit in this turn is the Mormon Church's stand against homosexuality, indicating that the ideal way by which Mangels could reconcile his Mormon principles regarding the community and his sexuality is to turn to Wonder Woman as a socially progressive ideal. This underscores the most radical aspect of Marston's conception of Wonder Woman, for if, as DiPaolo notes, "Wonder Woman fights for America because America fights for women's rights around the world" (2007, 155), then one is compelled to admit that the nation has failed to achieve this goal and that patriarchy has to be replaced with matriarchy in order to achieve it. At her essence, then, Wonder Woman is the progressive embodiment of America as a redeemer nation. The early issues of the comic book expressly conflated her World War II narratives with biographies of prominent women in a regular feature titled "Wonder Women of History." This celebration of important women throughout history offers a counternarrative to the prevailing historical record, which emphasizes the accomplishments of men to the near exclusion of women. Therefore, in enacting the role of redeemer nation, fighting for women's rights throughout the world, Wonder Woman also necessarily serves as a redemptive figure for America itself.

[2.7] In November 1977, a National Women's Conference (designed in part to celebrate International Women's Year) was attended by 20,000 delegates in Houston, who came together "to debate and pass resolutions on subjects as varied as day-care financing, abortion and the Equal Rights Amendment" (Stanley 2005). During the conference Texas congresswoman Barbara Jordan, the first Southern African-American woman elected to the House of Representatives, opined, "No one person has the right answer. Wonder Woman is not a delegate here" (ibid.). Her observation in this context confirms that a progressive social vision requires the ideal of Wonder Woman, even and especially when that ideal is not realized. The obverse to Jordan's statement is that an incipient Wonder Woman resides within all of the delegates in attendance, otherwise the very goals of the conference—to advance women's equality—would be impossible daydreams ("A thousand years in the future!"). The event's articulation of a public sphere is validated by the presence of congresswomen and its sponsorship by the federal government. In fact, the conference was the result of President Ford's 1974 executive order to create a National Commission on the Observance of International Women's Year "to promote equality between men and women" (Freeman n.d.). Significantly, the conference as originally proposed by Representative Bella Abzug was to be held during the nation's bicentennial year, timing designed not just to highlight the compatibility of feminist causes with defining national values, but to insist that those values would remain a utopian dream until women were accorded equal status as citizens. Thus a kind of futurist nostalgia, in which the delegates to the conference referenced the Constitution as a defining text for the nation's future, underscores the mission of the conference and further indicates the resonance of Wonder Woman as a commodity figure suspended in a dynamic, yet static, middle ground between the past and the future.

[2.8] Perhaps the most significant strategy by which the seemingly impossible future ideal of Wonder Woman can be realized is a turn to the past and the affective power of nostalgia, a turn to history's wonder women in order to inspire women in the present. The superhero is a commodity signifier strongly linked to childhood, and while the visual and narrative excesses of the genre speak directly to the affective capacity of childhood play, the superhero also speaks specifically to the transcendent agency of imagining a new social self. This imagining is the most directly useful function of the superhero in adulthood. Feminist icon Gloria Steinem expresses this in her own reflections in the 1970s on her relationship to Wonder Woman and in her response to alterations to the character at that time. In 1968, in an effort to rejuvenate sales of the Wonder Woman comic book, DC Comics took the controversial step of stripping Wonder Woman of her traditional costume (replacing it with contemporary mod fashions) and removing her powers. Writer Denny O'Neil reflects, "I saw it as taking a woman and making her independent, and not dependent on super powers. I saw it as making her thoroughly human and then an achiever on top of that, which, according to my mind, was very much in keeping with the feminist agenda" (Daniels 2000, 126). Not surprisingly, feminists like Steinem strongly disagreed, seeing this corporate maneuver to boost sales as yet another example of masculine authority containing the perceived threat of female agency. In fact, since Marston's death, Wonder Woman had been increasingly altered to conform to a more traditional concept of femininity. Through the 1950s she became more romantically interested in Steve Trevor and even required his rescue on occasion (reversing the dynamic Marston had established between them). Also, during this period the feature "Wonder Women of History" was replaced by "Marriage à la Mode," documenting wedding customs around the world (ibid., 102).

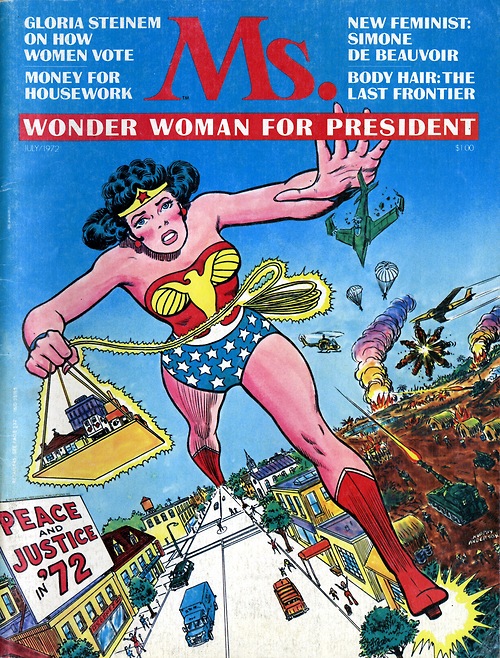

[2.9] All of these containment strategies are directly addressed by the cover of the debut issue of Steinem's Ms. magazine (July 1972), which features a larger-than-life Wonder Woman in her original costume, striding down a street and swatting aside a fighter jet while an army tank fires on her (figure 2). Her stance against obvious symbols of patriarchal military power is reinforced by a billboard that proclaims "Peace and Justice in '72." Under the Ms. masthead a banner reads "Wonder Woman for President," which, linked to the billboard message, asserts (in contrast to the cover of Wonder Woman no. 7) that the dream of a female president can and should be a reality in the present. The cover is a direct response to the deferral of matriarchal authority for a thousand years and a strong refutation of masculine modes of agency, as well as a direct reclamation of Marston's Wonder Woman. Tellingly, in the same year that Ms. debuted, Ms. Books published an anthology of 1940s Wonder Woman stories that further exploited the nostalgic power of the original concept of Wonder Woman in order to reclaim the character from her then-current diminution at the hands of DC Comics. Steinem provides introductions for all of the stories in this volume and, like Mangels many years later, she asserts a proprietary claim on what she considers to be the character's essence by turning to affective childhood memories. In the anthology Steinem recalls her "toe-wriggling pleasure" as a child reading about "a woman who was strong, beautiful, courageous, and a fighter for social justice." Expressing her own wishful thinking, Steinem promises the return in the contemporary comics of "the original Wonder Woman—my Wonder Woman" (Marston 1972, n.p.). This return to the past is presented as the necessary means to achieve social progress in the present as circulated through individual affect and memory. Steinem enacts the primary strategy of returning to a childhood subjectivity in which the child as consumer-citizen has the social agency to imagine a more progressive America.

Figure 2. A Wonder Woman for a new era.[View larger image.]

[2.10] As Sara Ahmed observes, a memory "can be the object of [one's] feelings in both senses: the feeling is shaped by contact with the memory, and also involves an orientation towards what is remembered" (2004, 7). In the case of Steinem and Wonder Woman, the initial memory (the utopian point of origin of the consumer-citizen's political consciousness) and all subsequent contact with it are mediated by the auratic object, in this case Wonder Woman comics of the 1940s. Of course, that first contact is already disciplined according to ideology: we learn how to react to something before we ever see it. This discipline informs competing notions of American identity: both conservative and progressive readings of the nation are grounded in its imagined (fantasized) origin, which is then used either to valorize this past as an ideal to be returned to or to argue that the ideals of the nation have never been realized but can and should be.

[2.11] When a mass culture sign such as Wonder Woman is so strongly linked to a contested understanding of national ideals, the fluidity of her signification makes her accessible both as a commodity and as a progressive symbol. Thus the consumer-citizen has a "memory" of her before there is a contact event to remember. She is an imagined subject before we ever encounter her; thus the object is always working as part of an imaginary, never separate from it. As an idealized figure defined by visual and narrative excess, the superhero is particularly available for this mediation of internal fantasy. Fans like Steinem have an affective memory of Wonder Woman as a feminist icon, however qualified her feminist agency may be in post-Marston comics. This indicates the significant degree to which superhero texts rely on narratives of emotion. Typically in the genre the primary affective modes are a mixture of fear, anger, and awe at threats posed to society and the superheroic response that society necessarily produces. Marston's Wonder Woman is again unique in that her narratives rely much more on the more accessible affective power of love than on these masculine-oriented emotional tropes. The emotional valence of commodities confirms what Ahmed (2004, 13, 90) calls an object's "stickiness," which is "an effect of the histories of contact between bodies, objects, and signs." This can also be characterized as the superhero's resonance or aura, produced in the history of affective exchange between superhero texts and fans. Therefore, not only are Wonder Woman texts diegetically defined by the affect of love, but so too is the consumer-citizen's relationship to (and memories of) the commodified icon. When it is linked so intimately with childhood (as Steinem and Mangels testify), we see that the loving memory is directed equally at one's childhood self, indicating the utility of the mass culture object as the mediating device between internal subjectivity and exterior social agency, between the private self and public culture, between the past, the present, and the future. This mediation facilitates the creation of Wonder Woman Day as a public response to the private, hidden traumas of domestic violence.

[2.12] The affectivity of the superhero genre serves as a bridge between individual and collective, materializing and asserting emotional ties that bind. We "imagine" (per Benedict Anderson's concept of the nation as an imagined community) how and why we respond affectively to a text as others do, or as we think they should. Consequently, Mangels's project depends upon a particular orientation to what is remembered that conflates mass culture, civic identity, and personal memory and is substantiated by the affirmation of shared affect in the moment of the event. Wonder Woman Day, then, is equally about domestic violence victims, Wonder Woman, and fans. Wonder Woman Day becomes the latest iteration of a progressive American dream, linking the individual consumer-citizen to the public sphere via the affective commodity object. This redeemer nation myth that so strongly defines American identity is significant, given that Mangels's devotion to the character originates during perhaps the most prominent period of mainstream feminist visibility, the early to mid-1970s. Thus his fan agency is born in an affective moment of political agency (the continued national push for ratification of the ERA in 1976) that also links the consumer-citizen to two other determinant events: the nation's bicentennial and the debut of the Wonder Woman television show. The symbolic rebirth of the nation on its birthday and of Wonder Woman in this fresh television iteration informs the symbolic rebirth and transformation of Mangels into a politically conscious consumer-citizen. As with the unrealized progressive vision of the Equal Rights Amendment, and consistent with the necessarily open textual nature of Wonder Woman as a mass commodity, Mangels must make his own subjectivity available for renegotiation and transformation.

3. Wonder Woman to the rescue

[3.1] Comics speak, without qualm or sophistication, to the innermost ears of the wishful self.

—William Marston (Daniels 2000, 11)

[3.2] Sensation Comics no. 15 (March 1943) featured a public service announcement about infantile paralysis from the March of Dimes that was composed as a comic book story. In the one-page narrative, Queen Hyppolyta observes Wonder Woman "in the man ruled world" carrying a sick child to a hospital, where the little girl is placed in an iron lung. Wonder Woman explains to her mother that "Americans celebrate their president's birthday by giving parties to raise money for this tremendous work!" Hyppolyta responds, "That's wonderful! You must help!" Later Wonder Woman receives an urgent message on her "mental radio" from Steve Trevor: "Calling Wonder Woman! My desk is swamped with letters asking for your picture! Do your fans think I'm a photographer? You answer them!" Wonder Woman exclaims, "Mother, an idea! I'll give my picture to every child who sends me a dime for the president's birthday fund!" The PSA offers "every boy and girl in America" an "autographed" picture of Wonder Woman when they send in a dime that will be donated to the March of Dimes. This PSA articulates and directs the nexus of consumerism, fan affect, and compassionate citizenship through the figure of Wonder Woman. Authorized by her mother and inspired by consumer demand, Wonder Woman intertwines the already conflated events of the president's birthday and the charity drive with her own commodity status. The result is a "personalized" commodity (Wonder Woman's ostensible autograph, an externalization of internal fantasy) that confirms the fan's affective attachment to Wonder Woman and compassionate agency as an American.

[3.3] This very reflexive condensation of consumer-citizen subjectivity via Wonder Woman reflects a trend to reconcile the responsibilities of citizenship with the role of consumer in this relatively new era of mass culture. As Lizabeth Cohen observes, by the late 1930s it was generally held by manufacturers, economists, and the government that the buying power of consumers would not only bring the US out of the Depression but also preserve American democracy (2003, 20). Thus the act of purchasing a Wonder Woman comic would reflect and confirm the rhetorical value of the superheroine as a defender of American values (which this process increasingly defines according to free-market capitalism and consumerism). The New Deal desire to boost consumer demand was equated with "the enhancement of American democracy and equality" (55), and this intersection of consumer and citizen agency was only amplified with the advent of World War II. According to Cohen, "To ensure the speedy arrival of…[a] postwar utopia of abundance, patriotic citizens were urged to save today (preferably through war bonds) so that they might become purchaser consumers tomorrow" (70). Again, citizen-consumer subjectivity coalesces via the figure of the superhero and in the consumption of superhero comic books, which frequently featured characters urging readers to buy war bonds. In Wonder Woman no. 2 (fall 1942), for example, Wonder Woman exhorts a crowd to "buy war bonds and help America banish war forever!" Civic duty is conflated with Wonder Woman's nonviolent rejection of all war, not simply an embrace of victory in the present one, thereby directly refuting the strategies of patriarchy by which recurring war coheres the nation-state. The low-cost purchase of superhero comic books allowed consumers to buy into the fantasy of American exceptionalism and triumphalism over the Axis, the Depression, and the aggressive nature of masculine politics. Wonder Woman thus serves as an indication of the utopian affect that is to follow victory over these elements.

[3.4] While postwar consumption attempted to fulfill "personal desire and civic obligation" (Cohen 2003, 119), the inherent tension between these two positions became progressively apparent. Wartime hegemonic values were increasingly challenged by a rising tide of cultural pluralism that was facilitated by the very machinations of mass culture that had done so much to promote this hegemony. Thus, as Cohen notes, "It was no accident that the rise of market segmentation corresponded to the historical era of the 1960s and 1970s…where people's affiliation with a particular community defined their cultural consciousness and motivated their collective political action" (308). As is evident on the cover of Ms. no. 1 and in DC's nonsuperheroic Wonder Woman, the identity politics of this period informed the reception of Wonder Woman from the late 1960s through the run of the television show (which aired from 1975 to 1979). From these two examples we can see how commodity culture could be appropriated for overt political agency and that such agency was resisted by the corporate gatekeepers of hegemonic values. The irony here is that the use of Wonder Woman as a feminist icon is thoroughly consistent with Marston's conception of the character, while DC Comics' radical revision of her in 1968 contradicts it.

[3.5] By 1973 DC had brought Wonder Woman somewhat closer to her origins, returning her powers and costume. Following Denny O'Neil's problematic claim that taking away Wonder Woman's powers made her a more powerful feminist icon, her final nonsuperpowered appearance, in issue no. 203 (Nov.–Dec. 1972), bore the cover blurb "Women's Lib Issue," suggesting that, according to DC, feminism and superheroines could not coexist. In 1981, under the guidance of publisher Jenette Kahn (note 1) and with the support of Steinem, DC acknowledged the character's fortieth anniversary by establishing a Wonder Woman Foundation, "dedicated to advancing the principles of equality for women in American society" (Gloria Steinem Papers). Kahn said that the awards granted by the foundation "are unique. They are the only financial awards given to women over forty, the only awards that honor inner growth and richness of character" (Daniels 2000, 151). The creation of this foundation was also integrated into the narrative of Wonder Woman no. 288 (February 1982), where it served as Wonder Woman's motivation for changing her costume (yet again), replacing the gold eagle emblem on her chest with a gold double W (that still resembled an eagle, emphasizing the intimate relationship between commodity and national iconicity). The foundation is thus conceived of as both a variation in the commodity icon and a means of civic engagement, both for Wonder Woman in her diegesis and for fans who are affectively incorporated into the project of the real-life foundation. Again, civic engagement (for the first time aligning fan and Wonder Woman with an expressly feminist cause) overlaps with mass culture production and consumption.

[3.6] While the Wonder Woman Foundation no longer exists in either the comic books or reality, it remains the defining utopian ethos behind the revised costume that is still used today, confirming the power of externalized fantasy. In Wonder Woman no. 5 (May 2007), Wonder Woman assists a shelter for domestic violence victims that was founded by women inspired by her to take control of their lives. The inherent instability of Wonder Woman, crystallized by her costume changes and mutable relationship to Marston's concept, indicates not only her function as a commodity that is constantly altered to renew market interest, but her availability for fan appropriation for social critique. The tension between producers and consumers informs Paolo Virno's concept of the multitude as a political designation separate from state authority. Virno presents the concept of the multitude in response to the concept of "the people," a notion of a national collective cohered by a homogenizing affiliation with the state. Conversely, according to Virno, the multitude "signifies plurality—literally; being many—as a lasting form of social and political existence, as opposed to the cohesive unity of the people. Thus, the multitude consists of a network of individuals; the many are a singularity" (2004, 76). The concept of the multitude calls for the deconstruction of the binaries of public and private and of the collective and the individual that the state is invested in. Turning to Marx, Virno goes on to assert that because it is "difficult to separate public experience from so-called private experience…even the two categories of citizen and of producer fail us" (24). Because mass culture has routinely conflated the roles of citizen and consumer, the division between consumer and producer is equally untenable. Since consumption cannot be articulated effectively as an exclusively private experience, the space in which it occurs or is recirculated is of primary importance. This allows us to understand more completely the significance of holding an event such as Wonder Woman Day at a comic book store, for, as Virno argues, the "'publicly organized space'…mobilizes political attitudes" (63).

[3.7] By choosing to hold Wonder Woman Day at Excalibur Comics, Mangels confirms the retail site as a primary locus of socialization and fantasy. He chose this particular store because it is co-owned by a woman (Debbie Fagnant, a Wonder Woman fan herself) and because, according to Mangels, the event "meant something to the people involved" (pers. comm.). Public affect as a mode of civic engagement is authorized by this structuring context of the comic book store charity event. Wonder Woman Day therefore validates the call in the 1940s and 1950s for a condensation of consumer and citizen identities. Wonder Woman Day becomes an explicitly progressive expression of this condensation, indicating that mass culture and progressivism are compatible when the intersection between production and consumption cultures is negotiated by the utopian expressions of fans. By choosing a retail space as the site for a charity event, and by using a comic art auction as the primary means of raising money, Mangels reifies the progressive redeemer spirit of Wonder Woman, realizing the potential for social agency that is embedded in fandom, a group that has been stereotyped as lacking such agency.

[3.8] This agency is publicly performed as transformation, making visible the secret "super" identity of the self, the comic book store, and the nation. Just as Wonder Woman assumes the everyday guise of Diana Prince but reveals her true identity at times of crisis, fans confirm their authentic super-citizen selves through their participation in Wonder Woman Day. Diana Prince's transformation into Wonder Woman is a visual embodiment of the moral values that already define the subjectivity of the consumer-citizen. Thus it is not coincidental that cosplay is a central ingredient of Wonder Woman Day. The transformation of the store and the self as a means of affirming the values represented by Wonder Woman reflects Virno's belief that a moral self is central to the political subject's identity. According to Virno, the ultimate place of refuge is "the moral 'I,' since it is…there that one finds something of the non-contingent, or of the realm above the mundane" (2004, 31). Thus, for a day, consumer-citizens are given the opportunity both to retreat symbolically into the discrete public space of the comic book store/charity event and to actualize social agency for the improvement of society. In the same manner that Superman retreats to his Fortress of Solitude and Batman to the Batcave, fans go to Excalibur Comics on this day to reaffirm the values that equally guide their consumption and their citizenship by embedding themselves in a space defined by fantasy and its separation from the everyday. The result is a twofold affirmation of a utopian vision for both society and oneself, for, as Virno says, "The feeling of the sublime…consists of taking the relief I feel for…refuge and transforming it into a search for the unconditional security which only the moral 'I' can guarantee" (ibid.). Tellingly, this process duplicates the dynamic that is at play within the domestic violence shelters the event was designed to support, further aligning both domestic violence victims and their supporters as citizens.

[3.9] Through the politicized physical site of commodity and affect exchange (the Excalibur Comics shop), fans assert the moral I as an extension of the authorizing figure of Wonder Woman, confirming the inherent meaning of both self and commodity figure, as well as the desired meaning of the nation. The moral I is realized by transcending the adult-child binary that typifies superhero fandom, an affirmation of both the morality and play that ideally define a child's subjective relationship to superhero texts (figure 3). The moral condensation of consumerism and state authority (itself a kind of utopian realization) is further confirmed by the fact that, beginning in 2007, Portland mayor Sam Adams officially proclaimed the day of every one of Mangel's events to be Wonder Woman Day for the city. In 2010 he declared, "The City of Portland recognizes that all residents of the State of Oregon should be able to embrace true equality for everyone, truthfulness, strength, safety, dignity, and peace" (http://www.womenofwonderday.com/WWDay5/WWDay5.html). This state project is consistent with the aims of the organizations that Wonder Woman Day supports. For Wonder Woman Day 4 in 2009, Amy Williams, director of development for the domestic violence agency Raphael House of Portland, issued this statement: "One of the most amazing things about Wonder Woman is the way that her appeal and message cross the traditional lines of generation, gender, race and class. Our vision at Raphael House is to engage this entire community in non-violent living, and being part of this event is an annual step toward realizing that vision" (http://prismcomics.org/display.php?id=1804). Thus we see that the shelter, the city, and the comic book store are extensions of the home as the site of both play and moral education, with Wonder Woman and fan subjectivity the governing forces at the heart of this intersection.

Figure 3. Reifying utopia, Wonder Woman Day 2008.[View larger image.]

[3.10] As Sandvoss confirms, "Fandom best compares to the emotional significance of the places we have grown to call 'home,' to the form of physical, emotional and ideological space that is best described as Heimat" (2005, 64). On Wonder Woman Day, Excalibur Comics emphasizes its capacity as Heimat, a morally safe space in which the marginalized qualities of comic book fandom are reconceived as vanguard qualities; the margin that comic book superhero fans occupy is at the forefront of society, not the sidelines. Therefore, if Heimat is "an extension of one's self, and the self [is] a reflection of place and community" (65), then Wonder Woman Day not only asserts an ideal utopian self for the fan, but also defines that self as a critique of social failures. Thus, the remediation of the comic book store as a charity gathering is a reconfiguration of Wonder Woman's feminist utopian home, Paradise Island. In the "simultaneously projective and introjective relationship between fan and object" (81)—in dressing as a superhero or purchasing original Wonder Woman art donated for Wonder Woman Day—fans confirm their latent superheroic qualities and productively attach themselves to "dominant social, cultural, economic and technological systems" (82). Such fan activities thus become modes of mastery and control over mass culture, society, and self simultaneously.

[3.11] The basis for this exchange between consumer-citizens and the commodity icon is compassion, which, according to Lauren Berlant, "implies a social relation between spectators and sufferers" and the obligation "on the spectator to become an ameliorative agent" (2004, 1). Berlant recognizes the inherent critical qualities of compassion, noting that a "national dispute about compassion is as old as the United States and has been organized mainly by the gap between its democratic promise and its historic class hierarchies, racial and sexual penalties, and handling of immigrant populations" (ibid). This gap is what motivates Mangels's desire to make Wonder Woman Day a family-friendly event and to work for a cause that touches victims of both genders and of all races, classes, and sexual orientations. During the Cold War, the rise of group identity politics was regarded as a direct threat to traditional concepts of liberty that saw it as an affirmation of individualism and not, paradoxically, collectivism. The tension between individualism and the nation is mediated by the power of mass consumerism as a means of expressing individual rights and identity within a broader collective framework defined by the shared values of capitalist democracy, values that are necessarily opaquely defined. Importantly, it is affect that both sustains and glosses over the tension between these ideological positions. The exercise of rights is an affective demonstration; we "know" how valuable our rights are (what they affectively "mean") according to how strongly we feel about them. The essential difference between the conservative and progressive ends of this demonstration is the difference between the masculine-inflected affect that so commonly defines the superhero genre (the reactionary affects of fear, anger, and awe) and the feminine-inflected affect of love that Wonder Woman interjects into this milieu.

[3.12] The difference between these two affects is, in other words, the difference between the power of love and the power of aggression. According to Ahmed, "Through love, an ideal self is produced as a self that belongs to a community; the ideal is a proximate 'we'" (2004, 106). We see this love at work in the diegesis Marston created for Wonder Woman: the utopian space of Paradise Island is not simply a refuge from the world of men but an affirmation of the moral I, bonding Amazons according to the affect of love. We further see it in fan devotion to Wonder Woman or a particular artist, so that the love for an original sketch that a fan might bid on on Wonder Woman Day becomes, by extension, an expression of love for people (domestic violence victims, other fans) and spaces (the comic book shop, the city, the nation). As Ahmed says, to love an object is to love oneself, and "such a love is about making future generations in the image I have of myself and the loved other…which can be bestowed on future generations" (129). When the object being loved is Wonder Woman, the inherent pluralism of America is celebrated. As Ahmed points out, from the perspective of multiculturalism, "difference is now what we have in common…you must like us—and be like us—by valuing or even loving differences" (138). Central to this love are the liberating capacities of Wonder Woman as a fantasy expression of a utopian American society defined by submission to loving authority. As Mangels says, "Superheroes can inspire, can raise consciousness, and can offer hope. Comic book fans can change the world" (pers. comm.).