1. Introduction

[1.1] As an "open source" project, Free Beer is much more than just a display of tangible open licensing. It is an example of the subversion of traditional forms of commodification and branding, and a reaction against the now-ubiquitous proprietary models of information and the strict parameters exerted by contemporary copyright laws. The past decade has seen several critics challenging current intellectual copyright norms—from the struggle related to accounting for digital works, to the increasing strain it places on creativity and innovation. This article, by examining some of these voices in the context of Free Beer, aims to place various views related to alternative understandings of ownership and accessibility into dialogue with one another—and with those not typically involved in conversations revolving around copyright (i.e., beer producers, consumers, and hobbyists)—in order to see how Free Beer uniquely engages the issues being raised and if any further implications can be discerned. On the one hand, Free Beer is about a particular campaign involving a popular alcoholic beverage; on the other hand, it is part of a broader conversation about innovation and transformation, along with the legal strictures that impede these processes. Thus, this article examines Free Beer in light of several related legal, technological, and cultural phenomena, including Creative Commons (CC)—the licensing suite providing the particular license used by Free Beer—free and open source movements, and remix studies.

2. Free as in beer

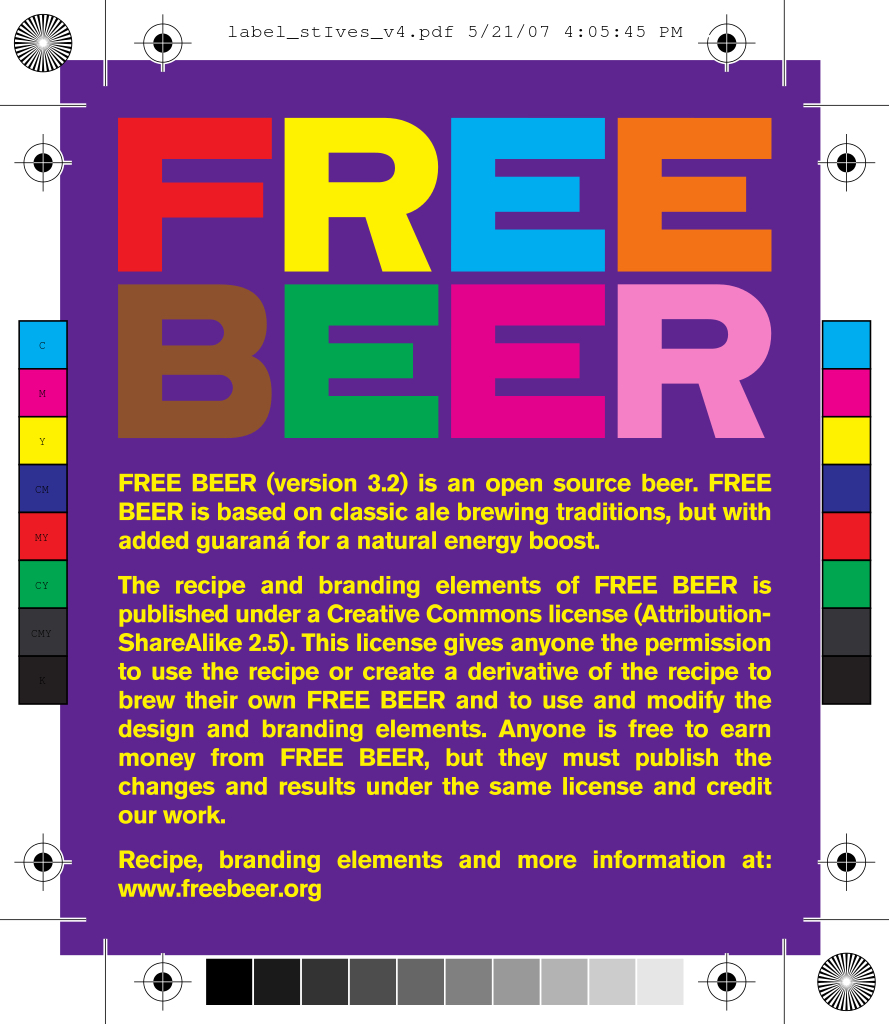

[2.1] The Free Beer movement emerged from a 2004 collaborative project between the IT University of Copenhagen and the artist-activist collective known as Superflex. Their aim was to apply concepts associated with Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) to a tangible product outside the digital world: beer. An "open source beer" was produced ("version 1.0") and its recipe published under a CC license. Superflex has since continued the project—transitioning to the "Free Beer" brand from the original "Vores Øl" ("Our Beer")—regularly releasing new versions of the recipe with the movement's official Web site (freebeer.org), based on public feedback and revisions to the original; the Free Beer web site reports that "version 4.0" (brewed by Skands Brewery in Denmark) is the most recent "official" version of the recipe. The production of Free Beer, using the artwork and branding made available by Superflex and freebeer.org, however, comes with the caveat of its particular licensing. As indicated by the bottle label for version 3.2 (figure 1): "This license gives anyone the permission to use the recipe or create a derivative of the recipe to brew their own FREE BEER and to use and modify the design and branding elements. Anyone is free to earn money from FREE BEER, but they must publish the changes and results under the same license and credit our work." Established breweries, for instance, could produce and sell the beer if they wanted to, as some do (figure 2), but they would be required to make the recipe, and any modifications, available to the public with the same stipulations.

Figure 1. Free Beer version 3.2. Design by Superflex, 2007. CC BY-SA 2.5. [View larger image.]

[2.2] Beer, as a widely appreciated and culturally pervasive social product, allows concerns over copyright and proprietary information to reach audiences that would be unlikely to be involved in software-inspired conversations. "Recognizing that beer consumption is—and beer brewing could be—a popular social activity that forms part of what one could consider culturally fundamental," Troels Degn Johansson (2009, 8) suggests that Free Beer might "facilitate social gatherings where ideas and creative communities could be celebrated and inspired to engage in further involvement." In "Free Beer and Engaging Tools: Chains of Analogies in Superflex," Johansson outlines the birth of the project and how it relates to Superflex's other work and guiding philosophical principles. According to Johansson (2009, 1), "FREE BEER is a beer brand that seeks to communicate the principles of free software, free creativity, and intellectual property rights as an urgent political issue by comparing a beer recipe with a piece of software." Unnecessary restrictions on creativity and innovation, Superflex maintains, are an impediment to both the creative process and to attempts to improve cultural works and activity. Framed as a work of art, Johansson (2009) places Superflex's Free Beer project into the context of political action and cultural critique, drawing on what he calls a lineage of "socially engaged artists"—including groups such as the French Situationist International: mid-20th-century political and cultural revolutionaries who regularly engaged artwork in their tactics. Johansson (2009) classifies Superflex's work—in Free Beer and across other projects—as "design art": art that is meant to create "tools" for people to effect change in the world around them. Indeed, the original name of the project, Johansson (2009, 6) notes, captures this sentiment: as an appropriation of an old Carlsberg Beer slogan ("Our Beer"), Vores Øl evokes the beer's "social dimension" through its inherent emphasis on everyone having the ability to brew the beer themselves (i.e., ours, not theirs) and "modify the original Our Beer recipe and its visual identity." But both names, Johansson points out, also signal a reclaiming of sorts—a reclaiming of products and ideas from large corporations that often exert copyright and proprietary ownership for the sake of monetary security and reward, not innovation and the bettering of society and its cultural works.

Figure 2. Free Beer from different breweries. Photograph by Superflex, 2007. [View larger image.]

[2.3] The Free Beer brand also signals a phrase associated with the Free Software movement, attributed to the founder of the Free Software Foundation (FSF), Richard Stallman: "To understand the concept [free], you should think of 'free' as in 'free speech,' not as in 'free beer'" (i.e., free as in liberty, not free as in gift). For the Free Software movement, "free" means the freedom to do whatever one wants with the software or code in question, including the redistribution of it in a potentially modified form, and even the sale of it for monetary purposes. Stallman argues that proprietary software perpetuates "instrument[s] of unjust power." Users, he claims, should "have the freedom to run, copy, distribute, study, change and improve the software"; anything short of this is considered unethical and rejected by the FSF (https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.en.html). While many use "free software" and "open source" interchangeably, Stallman and the FSF remain adamant about the differences between the two. Generally speaking, the latter is said to lack the ethical foundation of the former, and is more of a practical position related to the creation of a better program or product; without communal involvement, proprietary software is considered insufficient and inadequately equipped to handle the perfectionist task (https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/open-source-misses-the-point.en.html). Free and open source typically amount to the same outward appearance; the emphasis associated with each is what usually separates them. "Open source," however, has a rhetorical salience that can be applied to creative and cultural works as a whole in a way that surpasses the more limited nomenclature of "free software." It is important to consider the distinctions made by the FSF so that Free Beer can be properly situated in discussions revolving around alternative licensing schemes and criticisms of proprietary models. The majority of the licenses in the CC suite, for instance, tend to preserve the proprietary model, and end up falling short of what the FSF would consider "free" (note 1). Cultural works in both categories, however, facilitate transformation—when "something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message" is done to change a previously created work—in ways that proprietary models do not (http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/510/569.html). Indeed, this broader recognition of the freedom to "remix" aligns with the aims of various "free culture" movements (such as Students for Free Culture and QuestionCopyright.org), and law professor Lawrence Lessig's 2004 book Free Culture has served as a foundational resource for much of the ideology continuing to drive these types of campaigns and organizations.

[2.4] Lessig, a famous proponent of remix culture and of transforming the legal restraints inhibiting it, launched the CC license suite in 2003 in an effort to make it easier—in terms of monetary cost, time, and energy—for work to be both licensed for use and used by others (Lessig 2012). While preserving the proprietary model of information through most of its licenses, CC does relax inherent restrictions by offering a "Some Rights Reserved" framework as opposed to copyright's "All Rights Reserved." Moreover, Lessig's understanding of copyright might sound a bit paradoxical at first glance: it actually facilitates creation instead of restricting it. Lessig views copyright as giving people the incentive to create: if they cannot freely produce copies of protected works and reap monetary reward from them, for instance, then they will be encouraged to create something new instead. Creative repurposing, according to Lessig, should not be held to the same restrictions as copied, that is, plagiarized, works (Lessig 2012). The notion of "fair use," summed up by a statute in the 1976 United States Copyright Act, would seem to accommodate this position, but its application in legal matters can be a bit ambiguous—largely relying on the use, extent, and effect of the transformative works in question, which is obviously open to much interpretation and deliberation. According to Section 107 of the Copyright Act, use of copyrighted work under the following conditions does not constitute an infringement: "for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research" (https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html#107). In theory, this sounds great, and court rulings have been shown to lean in this direction when ruling otherwise would hamper the creativity these types of statutes are meant to facilitate and protect in the first place. One of the main problems encountered in real life, however, is when large companies that are not keen on sharing their copyrighted work overwhelm those they are accusing of illegally using or transforming it with litigation fees, thus creating unfair courtroom scenarios—and future legal hurdles if the accused are forced to fold (McLeod 2005). While fair use might help create "a space for artists to freely use elements of copyrighted works as long as the derivative work is transformative or doesn't freely ride on the presence of the original" (McLeod 2005, 155), for Lessig, that is simply not enough: "Fair use isn't freedom. It only means you have the right to hire a lawyer to fight for your right to create… Fuck fair use… We want free use" (McLeod 2005, 329). Lessig is more concerned with copyright law protecting against the exploitative copying of works without appropriate credit given to the authors and creators of those works upon which one is building—an ideal that aligns with the aims of CC. Quoting from the work of others, for example, citing them as sources in repurposed work, is perfectly fine, and something with which copyright should not interfere (Lessig 2012). Lessig is calling, then, for nothing short of the freedom for remixers to create.

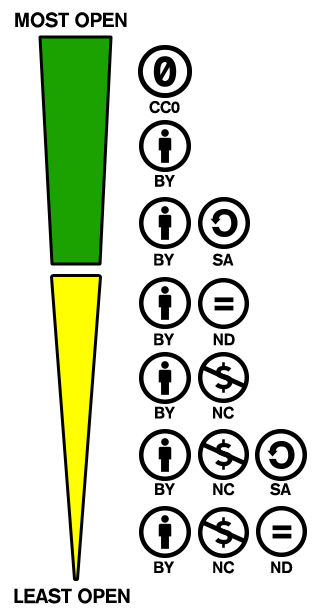

[2.5] Niva Elkin-Koren (2006, 327), in "Exploring Creative Commons: A Skeptical View of a Worthy Pursuit," notes the two main "barriers" to accessibility and use of information and cultural works: the legal right to restrict it, and the high costs associated with gaining it. CC, she explains, "accepts the first and focuses on the latter." CC does this by making multiple (and free) licensing options, which can be mixed and matched, available on their Web site (creativecommons.org) for users looking to license their work in a way that takes advantage of its aims (figure 3). Attribution (BY) accompanies all CC licenses, requiring users to credit/cite the creator of the work they are using; ShareAlike (SA) requires users who might modify the work to use the same licensing terms of the original if they choose to distribute it (Free Beer is under a CC BY-SA license, which is one of the least restrictive); NonCommercial (NC) prohibits the distribution of work for commercial/monetary purposes; and NoDerivatives (ND) allows only the exact replication of the work, with no modifications allowed. CC also employs its own mark for works users wish to place in the public domain ("No Rights Reserved"): CC0. As systematic and structured as it appears, however, CC does have its critics. Elkin-Koren (2006), for example, argues that the multiple options CC provides might end up causing the headache and monetary burden for both licensor and licensee—in trying to figure out which license is best, what the legal extent of use actually is, and what, exactly, is covered—it was meant to avoid. Another potential issue she raises is that since there is still such a focus on a proprietary model, CC might perpetuate the obsession with copyright and ownership/exclusionary authorship that free and open source movements are reacting to in the first place.

Figure 3. Creative Commons licenses. Image by Creative Commons. CC BY 4.0. [View larger image.]

[2.6] Among the authors surveyed in this article, Lessig is, perhaps, unique in his persistence that copyright should be preserved against the "control-obsessed individuals and corporations that believe the single objective of copyright law is to control use, rather than thinking about the objective of copyright law as to create incentives for creation" (Lessig 2012, 165–66). He openly confesses a belief that it is "an essential part of a creative economy" (Lessig 2012, 167). The problem, however, is that the digital world has engendered a confusing citation scheme where one must get permission for use prior to any actual creation (Lessig 2012). "Imagine how absurd it would be to write the Hemingway estate and ask for permission to include three lines in an essay about Hemingway for your English class," Lessig (2012, 157) bemoans. And he is right; but it would not just be absurd: it would be incredibly tedious and would likely result in fewer people committing to the production of what he calls "meaningful activity" (Lessig 2012, 164).

[2.7] An additional difficulty preventing the production of "meaningful activity" is that nontextual, multimedia works are difficult to "cite" in the traditional sense of the term, which makes the terrain difficult to navigate, both legally and creatively. For example, compared to citing an author in a research article, it is not as clear how to cite a video when creating a mashup that draws on previous productions. Lessig's main point is that current laws governing the use of work are inadequate and are progressively focusing more and more on the wrong side of production. The laws need to start making distinctions between copying and repurposing; the former amounts to plagiarism (an act Lessig facetiously argues is the only crime worthy of the death penalty) and unfairly benefiting from someone else's work, while the latter acknowledges the lineage of creation and gives previous creators and innovators the credit they deserve (Lessig 2012).

[2.8] Elkin-Koren (2006, 332) refers to the CC project as "a form of political activism" that is "best understood as a social movement seeking to bring about a social change." Thus, amid her criticism of the reliance upon the "proprietary regime," and considering the overall aims of CC—coupled with the underlying assumptions Lessig advocates—her assessment may actually support the critical dimensions of projects like Free Beer in a way that a complete dismantling of proprietary models might not. CC, she notes, is not replacing copyright with something else; it is transforming—remixing—copyright "in a rather subversive way" that changes its meaning and how it is exercised. And this—the exercising of copyright in an alternative and subversive way—CC advocates claim, is what allows for the emergence of a culture characterized by "meaningful activity" (Elkin-Koren 2006, 325).

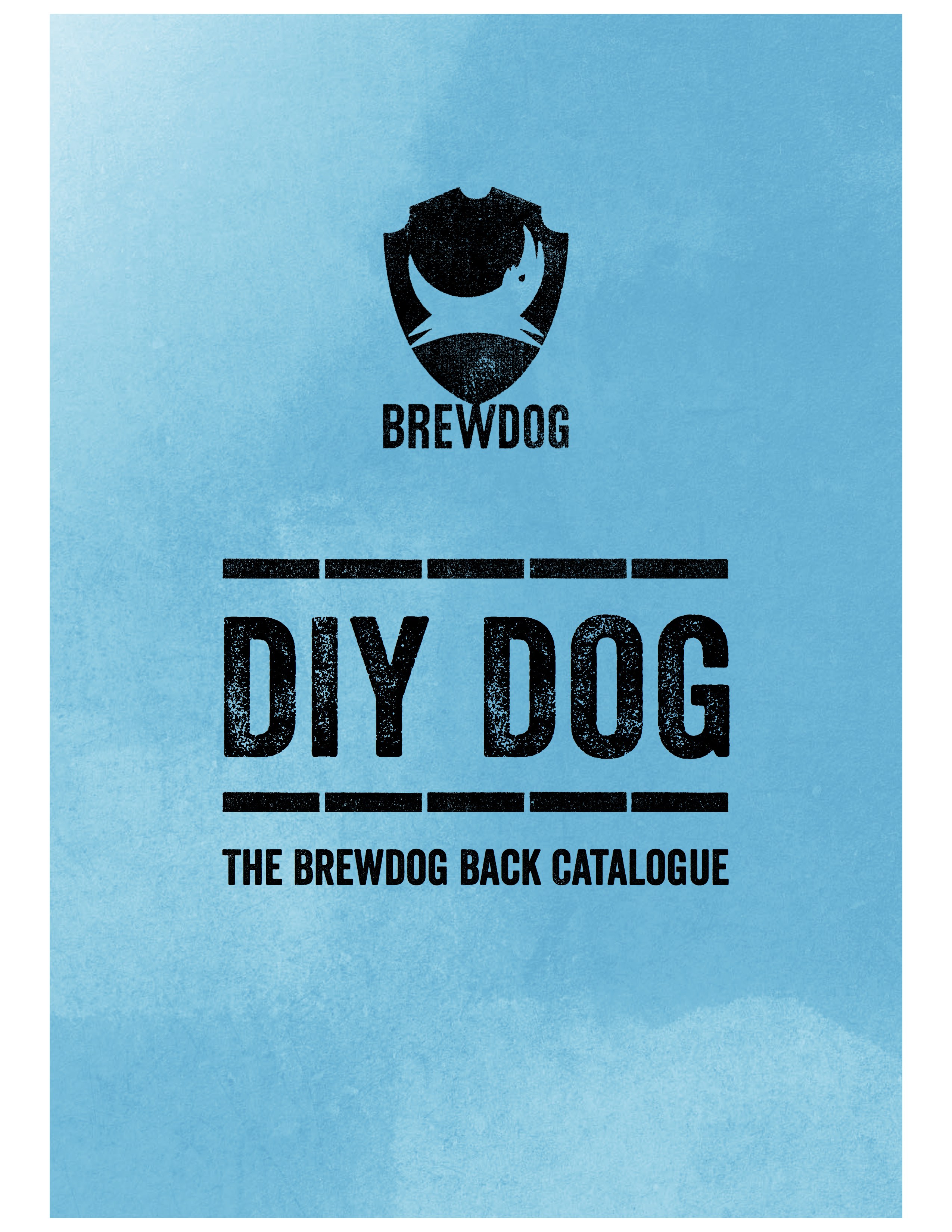

Figure 4. DIY DOG. BrewDog, 2016. [View larger image.]

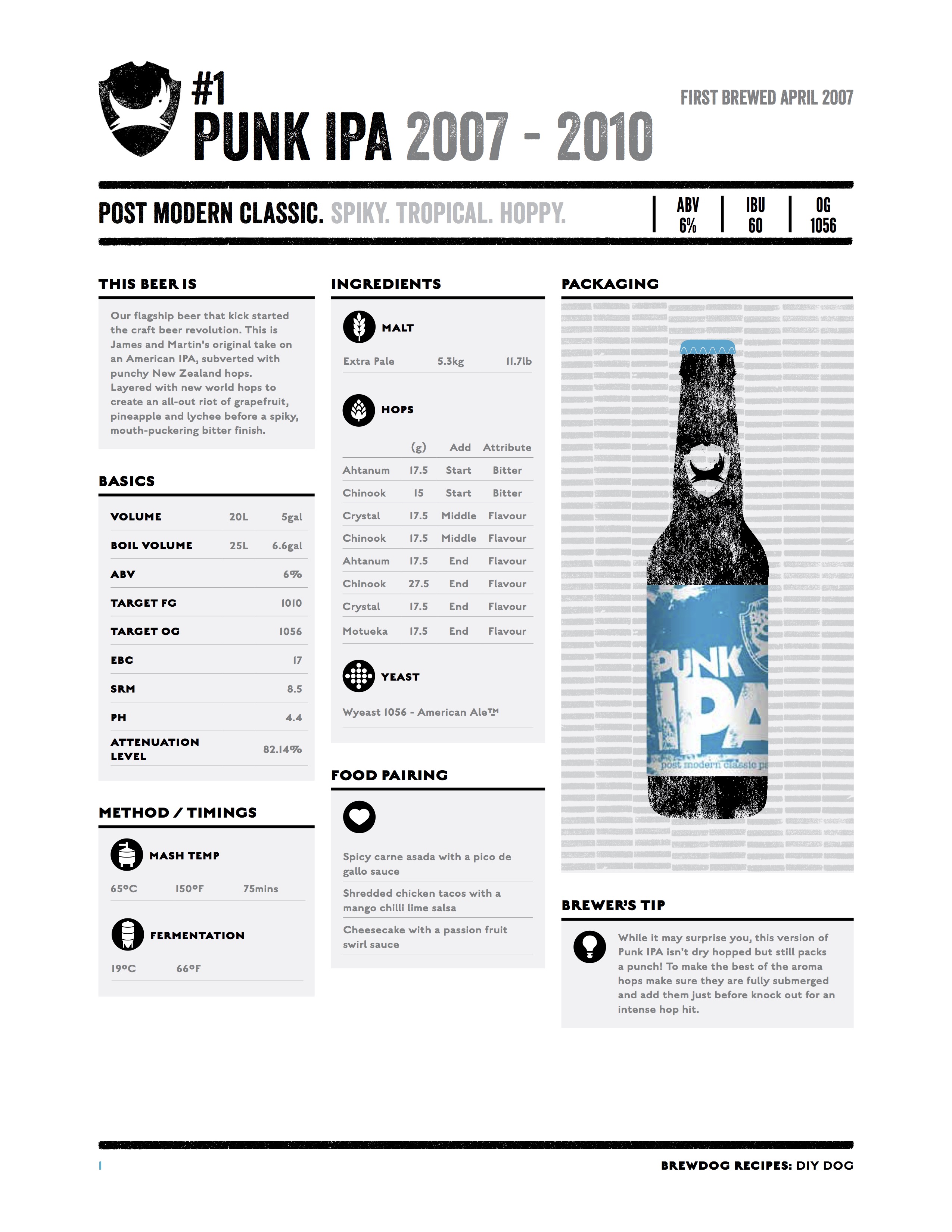

Figure 5. Recipe for Punk IPA. BrewDog, 2016. [View larger image.]

[2.9] Reflecting on BrewDog's (Ellon, Scotland) recent release of their entire recipe catalog online (figures 4 and 5) (https://6303ffd34a16b1ca5276-a9447b7dfa4ae38e337b359963d557c4.ssl.cf3.rackcdn.com/DIY%20DOG.pdf), Guardian writer Paul Mason (2016) demonstrates how such tactics within the beer industry play their part in reworking the taken-for-granted guiding principles of capitalist economies: "The idea that the basic tools of modern life should be free, shareable and collaboratively improved, with nobody allowed to make them private property, was born in the free-software movement, spread via the Creative Commons movement and is gaining traction in the world of physical products. It doesn't destroy capitalism, but it does challenge its dynamics." Indeed, a subversive practice itself necessarily builds upon the work, institution, ideology, and so on, that is perceived to be problematic, and a complete dismantling of copyright law is not only unrealistic, but, following Lessig, not exactly the point, or even the preferred outcome to be advocating: it is a beneficial framework that simply needs to be amended to fit the current digital, multimedia milieu. While Elkin-Koren's criticism does hold some merit, it functions best as a conversation piece—instead of fodder for abandoning CC entirely—for the wider discussion of freedom, open source, transformation, and licensing schemes that aim to subvert the extremism associated with contemporary understandings of copyright law and notions of intellectual property.

3. The default way of doing things

[3.1] In "Open Source as Culture/Culture as Open Source," Siva Vaidhyanathan (2012, 24) asserts that open source "used to be the default way of doing things," but since the 1970s and 1980s, when proprietary information models become much more prominent and influential amid rapidly developing technologies, it has become sort of countercultural, and any sort of affront to the system perpetuating these newer models is perceived as "radical, idealistic, or dangerous." But, the idea of community being inherently beneficial to production and innovation is what stands out most in Vaidhyanathan's work. Proprietary models can clearly contribute to the success of corporations and industries, but that does not mean open source models cannot help achieve the same thing. Vaidhyanathan (2012) argues that the latter might hold the potential to become even more beneficial, since the encouragement of communal development equates to more minds working together on a project's progress and goals.

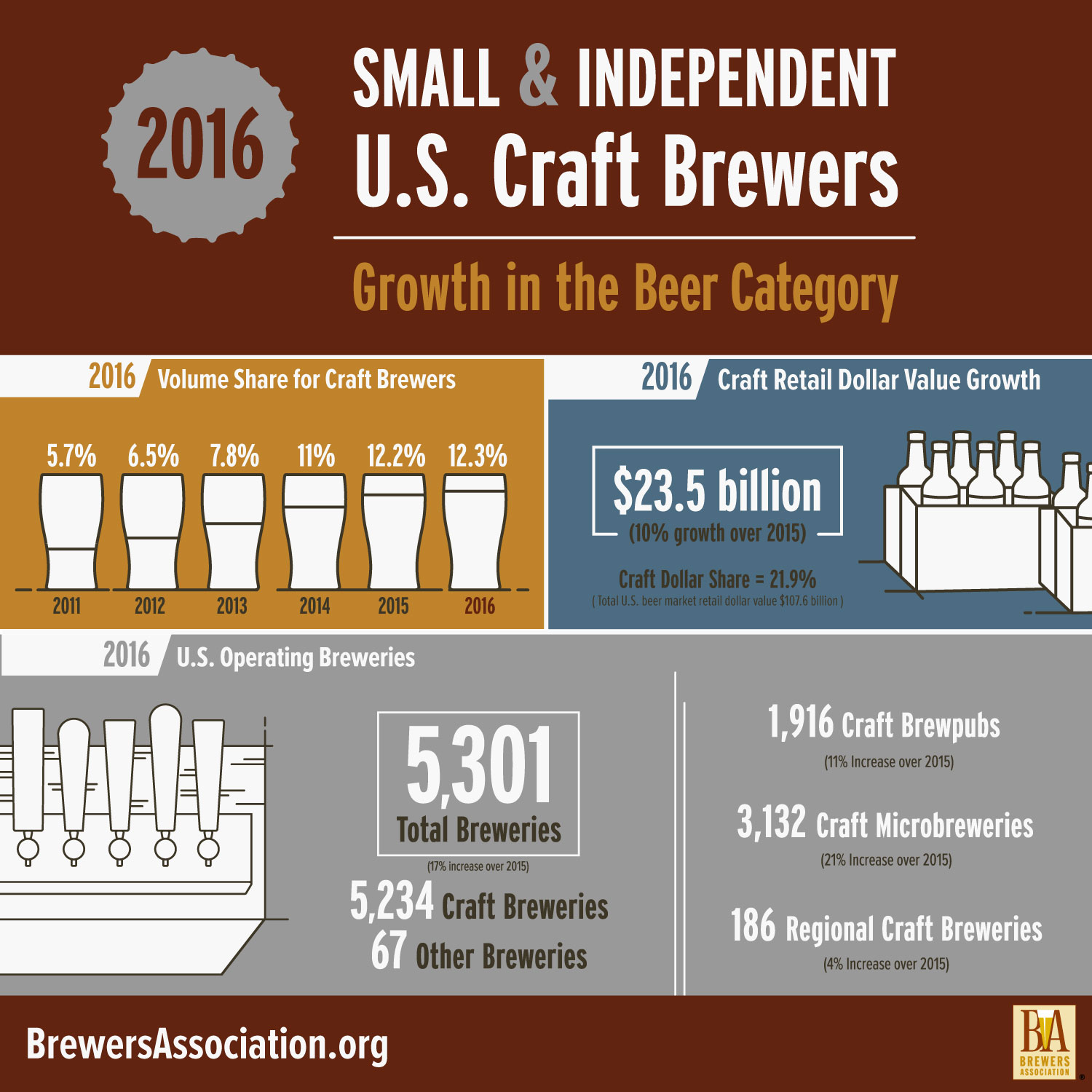

[3.2] Owen Gallagher (2013), in "The Assault on Creative Culture: Politics of Cultural Ownership," argues that artists should be free to adapt and repurpose work—to remix it as they see fit—since creative expression involves the production of works that ultimately benefit society and increase everyone's knowledge and the quality of their experiences. Indeed, this is the guiding aesthetic and satiating principle behind Free Beer: the production of the best beer possible by encouraging the participation of anyone willing. The craft beer industry is always remixing prescribed styles—maintained by organizations such as the Brewers Association and the Beer Judge Certification Program—molded by the creative whims of brewers playing with unique flavor combinations, quoting the guidelines as new variations are produced; American versions of traditional English styles, for instance (browns, pales, IPAs, etc.), have become remixed staples within the industry whose very existence depended upon the transformation of extant styles. While breweries and homebrewers regularly compete in competitions to see how well their versions adhere to the categories in these guidelines, standing out is largely the point, and continuing to transform previously prescribed frameworks is how they do so (for better or worse). The New England IPA, for example, is one such trend among American brewers that may result in a new style guideline (Moorhead 2016). Indeed, the continuing growth of the craft beer industry (figure 6) is evidence of the fact that variation in style is an inherent feature.

Figure 6. 2016 Craft Beer Growth Infographic. The Brewers Association, 2017. [View larger image.]

[3.3] Another recent trend is the production of "foraged beers"—beers made with ingredients that were actually foraged by the brewers in their immediate vicinity. This type of practice takes the repurposing and transformation of style guidelines to a completely different level: alternative and nonconformist compared to "official" styles. Homebrewers regularly engage in remixing commercial productions, too; the sale of "clone" homebrew kits and the proliferation of "clone" recipes across online homebrew forums are clear examples of this practice. Ballast Point Brewing Company (San Diego, California) interestingly adds to this hobbyist engagement through the release of its Homework Series: a series of bottled beers that feature a homebrew recipe (i.e., scaled down from typical production volumes) of the beer on the label to facilitate its recreation (https://www.ballastpoint.com/beers/homework-series/). MadTree Brewing Company (Cincinnati, Ohio) does the same thing, though under a CC BY-NC license, which indirectly encourages the remixing of the recipe for one's own enjoyment (http://www.madtreebrewing.com/beer-categories). Craft and homebrew communities inherently embrace remix and "meaningful activity" as standard features of their practice, which is what makes Free Beer a fitting vehicle to illustrate issues related to proprietary information models.

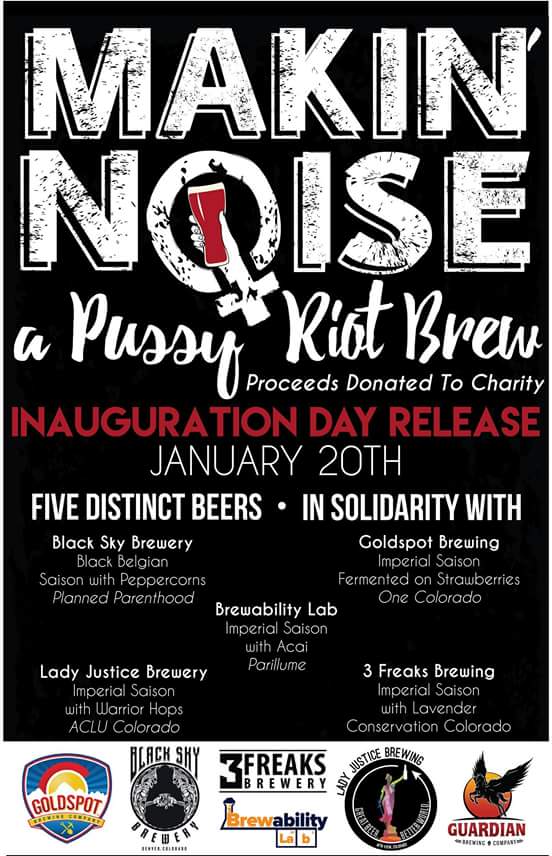

[3.4] Any craft beer aficionado will confess the same thing when it comes to appreciation, desire, and taste: they want to experience the best of the best. With a CC license, Free Beer emphasizes this point: the recipe can and should be built upon so drinkers can have the best beer possible. When as many minds, palates, and mash paddles as possible are joining forces to realize this vision, the industry and its corresponding culture arguably stand to benefit; though too many voices could add more confusion than construction, a carefully organized crowdsourcing of sorts could yield enormous qualitative potential. In 2007, tapping into this understanding, Flying Dog Brewery (Frederick, Maryland) released its Wild Dog Collaborator Doppelbock as part of its Open Source Beer Project: the recipe was posted on its Web site for others to comment on and make suggestions that would ultimately shape the final product (Harris 2007). Though it was only a one-time production, the beer successfully demonstrated how crowdsourcing a recipe could have mutually beneficial results. The industry itself, while still a player in a capitalistic system, is largely communal and cooperative; collaborations between breweries, and even festivals held in celebration of this, are regular occurrences. Rarely do breweries noticeably compete at the expense of each other. Denver, Colorado, has been hosting Collaboration Beer Fest since 2014, bringing together breweries from across the country to collaborate on special beers that showcase these communal and cooperative qualities to their fans. Cause-related brewing projects have also proliferated—especially since the election of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president of the United States. As a recent example, "Makin' Noise: A Pussy Riot Beer" (http://makinnoisebeer.com/) brought together five different Colorado breweries, represented by the women running them, to produce a beer that would benefit organizations related to women's and LGBQ rights. The first beer in the continuing series was tapped on Inauguration Day (figure 7), raising over $6,500 for local nonprofits (https://www.collaborationfest.com/blog/2017/3/13/makin-noise-a-pussy-riot-beer). Granted, care should be taken when engaging in broad, sweeping praise for collaborative beers within the industry. In other words, they are not always inherently better; Patrick Dawson (2016) reminds readers in The Beer Geek Handbook that compromise, an overdose of creativity, and a preoccupation with camaraderie rather than attention to production can overshadow the final product, which might result in not just a very mediocre beer, but a poor representation of the parties involved as well. Free Beer, however, is predicated on a "tried-and-true" ideological positioning, rather than a meeting-of-minds end result, emphasizing the ongoing (re)creation and transformation of something among those involved in order to make it better.

Figure 7. Promotional poster for Makin' Noise: A Pussy Riot Beer. Jax J. Gonzalez, 2017. [View larger image.]

[3.5] Michael Mandiberg (2012), in "Giving Things Away Is Hard Work: Three Creative Commons Case Studies," emphasizes the benefits of collaboration and communal involvement as well—specifically in regard to tangible creations. The underlying concern in his analysis is whether open source models help or hinder works that are not digital. Arguing for the former, through various examples, Mandiberg (2012, 191) concludes that being open and accessible invites more participation and involvement, which assists in the development and innovation of whatever is being created: "participation breeds creative mutation, and creative mutation leads to better ideas through this collaborative process." Responses from homebrewing communities and beer aficionados, weighing in on the earlier incarnations of Free Beer, were responsible for pointing out shortcomings in the recipe and its instructions—both in terms of its reproducibility and in its utilization of ingredients. While it would be impossible to definitively maintain that perceived flaws would not have been worked out on their own by producers of subsequent batches, the benefit of having that involvement and dialogue in fine-tuning the recipe is undeniable.

4. Plagiarism is the only crime for which the death penalty is appropriate

[4.1] A important question to consider, however, is whether or not everyone wants, or should want, to allow others to freely do anything they please with their work. This is a major concern taken up by Fred Benenson in "On the Fungibility and Necessity of Cultural Freedom." Benenson (2012, 180), while sharing the view of others mentioned above that "culture depends on original work being shared, reused, and remixed," notes the clash between those advocating for totally free licensing and those who use licenses offered by CC that are arguably still too restrictive, such as NonCommercial and NoDerivatives (figure 3). Free proponents, Benenson (2012, 181) notes, tend to embrace a "fundamentalist perspective of user-generated utopianism"; that is, the belief that all cultural works "should be able to be peer produced and should be licensed, released, and distributed in ways that facilitate derivatives and sharing." While the free software camp notices the potential to bridge the utilitarian and fungible nature of software tools such as operating systems and drivers to works in the physical world, the assertion that all cultural works should be free in the same way becomes problematic: a blurring of sorts between the work of art and the tools used to create it can occur (Benenson 2012). Benenson argues that while the freedom of fungible works makes sense, it is too extreme—and possibly counterproductive—to apply that same perspective to all culture, because it can upset the integrity of certain cultural productions. Worse, if creators start to believe that there is no difference between their tools and the products made by these tools, "we might end up disincentivizing them to create in the first place" (Benenson 2012, 185).

[4.2] To illustrate the difficulty in trying to apply this understanding to all cultural work, Benenson describes the experience of one user who used CC to protect his writings about his own medical condition. Fearing commercial exploitation, the author leaned toward a CC BY-NC-ND—one of the most restrictive licenses—but received quite a bit of pushback from members in the CC discussion forum where he was raising his concerns. Though the story ends without resolve (at the time of Benenson's publication, the author still had not assigned a CC license), it does demonstrate some of the important differences between software and other cultural works (Benenson 2012). Elkin-Koren (2006) notes that asserting rights obviously allows owners to exercise control, which can help them prevent others from taking freely produced work and selling it for profit without contributing to the community effort for creativity and innovation, or getting picked up by a third party and bundled into something restrictive. A personal, medical story being out in the world for free does not prevent companies from adapting it, or portions of it, for their own purposes (such as pharmaceutical advertisements), which can tarnish the very personal and creative work itself. In other words, Benenson's conclusion is that not all cultural works are meant to be directly built upon and revised by others—especially works that are considered nonfungible, such as the narrative in this example.

[4.3] Producers of works in capitalist economies do, however, need to make enough money to thrive and continue creating; ingredients used to brew and package a batch of beer, for instance, are not free, even if the recipe and marketing materials are. In other words, freedom to create does not equal freedom to exploit. Artists—and, by extension, artisans—Gallagher (2013) argues, should not be working for free, even if the work is freely available; there needs to be some sort of compromise between excessive limitations and stealing the work of others. Since the digital world has totally changed how all sorts of business models have functioned up to this point (e.g., hard copy products did not succumb to the extreme ease of reproducibility), Gallagher suggests the possibility of a type of collective patronage, or gift-giving scenario: artists give and fans return the gesture in order to actively help support them; in other words, an artist is funded by a network of fans to keep producing for their benefit. While arguably similar to brand loyalty, collective patronage is more than just a demonstration of support; it is more dialogic and dynamic than it is associative—"everyone becomes a beneficiary," Gallagher (2013, 91) states. But the point is that just because an object is open source does not mean that it has to be monetarily free: one can certainly sell work that is permitted to be adapted for reuse (such as Free Beer), as financial support and reward are essential components of socioeconomic interaction. BrewDog's catalog release, noted above, is a great example of this, since they continue to successfully sell their beer, despite the means to reproduce those products being in the hands of those fans purchasing it.

[4.4] Various critics also call for the criminal associations with "meaningful activity" to be abandoned. Gallagher (2013) argues that it does a disservice to both society and creativity when the remixing of works is criminalized. It is a flawed criminalization anyway, he states, since the argument that typically guides accusations is based on an infringement of intellectual property. According to Gallagher (2013), such property is not actually property in the technical sense of the term, since neither scarcity (borderline irrelevant in the digital world) nor effort (digital reproducibility is often as simple and effortless as a mere click of a button), the two most common justifications for property, are easily applied to cultural works. Elkin-Koren (2006) notes that part of this misunderstanding and misapplication has to do with the commodification of creative works: an associative blurring between physical, boundary-oriented property and self-expression has occurred, which confusingly attempts to apply physical barriers to abstract ideas and expressions. Such an understanding perpetuates a "reliance on property rights in creative works" that "reinforces the belief that sharing these works is always prohibited unless authorized" (Elkin-Koren 2006, 337). This is why CC is arguably so useful: it allows for access and lighter restrictions in a way that copyright does not, but it can also preserve the integrity of those cultural works that exist as exceptions to the fundamentalist perspective Benenson notes.

Figure 8. Access to Knowledge. Photograph by Mikael, 2007. CC BY 2.0. [View larger image.]

[4.5] The fact of the matter, Gallagher (2013) states, is that people are going to adapt, transform, and build off of work that came before them. That is how creative works work. Indeed, one of the shortcomings in Benenson's analysis is the failure to mention that just because a work is "terminal" and meant to stand on its own without being revised by others does not mean it cannot also be engaged to inform future work; for example, a particular sort of medical narrative might inspire others to reflect on their experiences in a similar way or model their own narratives after it. In other words, all work necessarily builds upon what came before it, even if the influence is seemingly indirect. According to Lessig (2012), trying to stop such inherent activity simply amounts to forcing unlawful behavior, not the prevention of creative expression. Criminalizing creativity, which results in driving that creativity underground, since it will continue to occur regardless of legal restraints, is both "extraordinarily corrosive" and corrupts "the premise of a democracy" (Lessig 2012, 168). The law itself, then, must shed its antiquated framework so that, rather than criminalize these artists for the sake of preserving some remnant of copyright models that equate ideas and expressions with property, it allows for creative repurposing. Free Beer, understood as a critical response to laws dictating how works are restricted and governed, uniquely engages this message both as an example of an alternate scheme of access and control and, being a tangible instance of remix, by bringing these issues outside of the digital realm to further emphasize the democratic dimensions that are currently at risk.

5. That which is always already remixed

[5.1] Jean Baudrillard (1993, 73), in a rather bleak and dismal qualification of reality as we know it, once claimed that "the real is not only that which can be reproduced, but that which is always already reproduced: the hyperreal." As emphasized throughout this article, underlying the conceptual framework of remix is a similar claim, though lacking Baudrillard's depressing characterization: everything is remix—everything, from ideas and expressions to tangible works and social processes, is always building upon what has been thought, created, and practiced prior to it. It may not always be blatant or obvious, but individuals and groups are necessarily inserting their own voices into conversations that have already been taking place. Vito Campanelli (2015, 72), in "Toward a Remix Culture: An Existential Perspective," notes that remix "involves all domains of human action" and is "an evolutionary duty essential to the progress of the human species"; the minor variations and fluctuations in biological evolutionary processes, for instance, even involve the repetition and innovation of previous genetic patterns. The use of "fragments of previous works is simply what human beings have always done in arts, in sciences, and in all fields of the intellect," Campanelli (2015, 72) notes, which is indicative of a state of "deep remixability": a condition in which everything—"not just the content of different media but also languages, techniques, metaphors, interfaces, etc."—can be remixed with everything (Campanelli 2015, 73–74).

[5.2] Campanelli (2015) also reminds readers that nothing is created from nothing. Humans do not create ex nihilo; they play with prior information for the purpose of producing new information. Such a perspective informs his understanding of "remix culture": a culture wherein "a work is never completed" but "functions rather as a relay that is passed to others so that they can contribute to the process with the production of new works" (Campanelli 2015, 68). Campanelli (2015, 79) refers to remixes from this perspective as never-ending "dialogic" processes, in that they "enrich the information already existing in the world so that others can creatively continue the game"—the dialogue. For Campanelli (2015, 77), remix culture becomes "the final destination of that process of disintegration of the modernist myth of originality." This is not to deny, of course, that individuals function as authors and creators of works; shedding this obvious fact would render even CC licensing schemes irrelevant by their very inception. Rather, what scholars like Campanelli are arguing is that if everything is remix, and if nothing is created from nothing, then the notion of original authorship—authorship that is entirely and systematically unique and self-contained, without reference or inspiration from anything else—is conceptually detrimental to how knowledge is advanced, especially when extreme protection and restrictions are placed on new information, severing that cord of accessibility through which others may also play with it. Both of these ideas, however—deep remixability and informed understandings of authorship and originality—are not so much revolutionary as they are stark reminders that creation is communal and social, and that any attempts to disregard or purge those defining attributes impede the very innovative practices that lead to the production of creative work.

[5.3] As a clear example of dialogical remix, Free Beer might be best conceived as what Byron Russell (2015) calls a "critical remix,"—a remix that focuses on a critical perspective. In "Appropriation is Activism," Russell (2015) notes that remix is capable of being critical of corporate, economic, and political power through its engagement and appropriation of original material. Through their critique of original forms, these types of remixes have the power to break the "codes and context of consumption" and use "the power of media to redress injustice, intolerance, and hegemony of discourse" in a "hacking," of sorts, of "the messages of corporate media" (Russell 2015, 219–21). A remix artist can "point to a trope, harness its power, reverse the message, and stimulate a moment of insight, all in a single action" (Russell 2015, 218). Critical forms of remix have a historical foundation in practices of détournement—"the reuse of preexisting artistic elements in a new ensemble" (Debord 1981, 55)—among the Situationists, who manipulated the original, underlying messages of cultural works and reapplied them in subversive ways (Russell 2011). While the Free Beer recipe is being remixed with each subsequent batch, it is also critically remixing proprietary models of information by employing an alternative "Some Rights Reserved" licensing scheme. Kalle Lasn, the founder of the Canadian "subvertising" magazine Adbusters, has made the subversion of mainstream advertisements and logos his specialty. Lasn (2000) argues that subversive tactics can help people see how things might be different, providing a glimpse of an alternative reality; in this case, an alternative to copyright laws that help keep media representations standardized and exempt from being hijacked and used outside of their preferred contexts and readings. Every time an interruption takes place—of the flow of images and information—there is a glimpse of "enlightenment," Lasn (2000) claims; those glimpses add up, and after enough people have had their eyes opened, a mass awakening can help dismantle the system. "Interrupting the stupefyingly comfortable patterns we've fallen into isn't pleasant or easy" (Lasn 2000, 107). "It shocks the system. But sometimes shock is what a system needs. It's certainly what our bloated, self-absorbed consumer culture needs." Revolution begins, he says, when "a few people start slipping out of old patterns, daydreaming, questioning, rebelling" (Lasn 2000, 108). If sitting around, drinking a few oddly labeled beers leads to this sort of revolutionary realization, then the project will certainly stand as a success.

[5.4] Nadine Wanono (2015, 389) takes the Situationist practice of détournement and reframes it as more than just an act of subversion: it "became a mindset, a dynamic, a loyalty to a revolutionary dimension outside of any political movement." In "Détournement as a Premise of the Remix from Political, Aesthetic, and Technical Perspectives," she indicates that the main goal of détournement is the destabilization of mainstream culture (Wanono 2015). Free Beer, then, might be thought of as a destabilizer of mainstream beer production, in particular, or of production, in general, when applied outside of its immediate context. But as noted above, it is about much more than just making great beer: through its engagement of alternative licensing schemes and its subversion of copyright, it is also about resistance against the impediment of creativity and innovation, and of the overall bettering of society, counter to the aims and ambitions of mainstream economic and exclusionary models. "The Situationists maintained that ordinary people have all the tools they need for revolution" (Lasn 2000, 109). "The only thing missing is a perceptual shift—a tantalizing glimpse of a new way of being—that suddenly brings everything into focus."

[5.5] Sonia K. Katyal (2012) argues that this sort of "perceptual shift" might involve a re-thinking of how we interact with and respond to cultural symbols and their meanings. In "Between Semiotic Democracy and Disobedience: Two Views of Branding, Culture and Intellectual Property," she outlines a remixed version of John Fiske's "semiotic democracy": what she calls "semiotic disobedience." The former, Katyal (2012, 50) indicates, refers to the engagement and use "of cultural symbols in response to the forces of media." Engaging and using cultural symbols in their own way, audiences are free to subvert and resist intended messages, which obviously conflicts with ideas related to exclusive ownership. But by drawing on historic forms of civil disobedience, Katyal (2012) offers a supplemental framework to Fiske's democracy: instead of just engaging the symbols of our culture—symbols that are owned and protected by corporate entities—semiotic disobedience aims to occupy corporate spaces, which includes consumer products—as forms of corporate property—in order to question and critique the symbols and their ownership. There is a specific emphasis throughout Katyal's analysis on interruption and occupation, over mere appropriation, which supplements critical dimensions of remix with a more activist edge. A semiotic act of disobedience takes place when "an individual actively transgresses the private, sovereign boundary of corporate property—a billboard, a domain name, an identity or a tangible product—and transforms it into a sort of 'public' property open for dialogue and discussion, an entity that is non-sovereign, borderless and thus incapable of excluding alternative meanings" (Katyal 2012, 59).

[5.6] It is easy to see how Free Beer relates to this as a critical and subversive campaign—one actively contributing to a conversation about far more than just allowing others to build on one's work in an easier, less costly sort of way. Critical remix and semiotic disobedience both aim to alter intellectual property by interrupting and occupying it, and then ultimately replacing it in the democratic way Fiske had envisioned (Katyal 2012). Brands, Katyal (2012, 53) notes, not only "help construct our identities, our expressions, our desires and our language"; they also become "important vessel[s] of corporate identity and property." Since brands also have commercial and political dimensions, they are perfectly suited to act as "powerful organizing principle[s] for political action" (Katyal 2012, 53). Anti-branding problematizes these aspects, using particular products to convey much larger questions and issues. Lasn's Adbusters delights in these techniques; and while Free Beer is not explicitly jamming up cultural symbols in the same way as Lasn and his devotees, it is still actively participating in a jam on current copyright law—and capitalist modes of production, more broadly—in order to subvert and shift the manner in which it is exercised. Occupying the space of a widespread consumer product, and inviting others to join in to engage with it in a democratic way, Free Beer becomes a "powerful organizing principle" as part of a much larger conversation and movement regarding action against information restriction and control.

6. A shift in perspective

[6.1] As indicated throughout this article, Free Beer, through its licensing and engagement of free and open source movements, participates in conversations and debates regarding current copyright law and its obvious shortcomings—which have become even more obvious alongside the rise of digital media and interaction. Framed as a critical remix on copyright law, the Free Beer brand demonstrates, in a semiotic disobedient way, that restrictions and prohibitions on not just creativity, but access and the ability to innovate and ultimately make the world—in a rhetorically pithy sort of way—a better place, can be lifted, dismantled, and repurposed to better suit contemporary circumstances. Probing and hacking the economic structures that have been in place, and that have pervaded commonsensical understandings of reality for an incredibly long time—challenging the dynamics of capitalism, Mason (2016) would say—is not an easy or painless task. And given some of the criticisms of both CC and free licensing schemes, the ambition does not even present a definitive or entirely clear path for doing so. But, as Lasn (2000) argues, sometimes what is not easy or clear is what is most necessary.

[6.2] One of the deeper implications of this analysis, however—and one that underlies the rhetoric and emphasis among those writing in this area—is the conceptual positioning of remix, as both a discursive framework and creative perspective. If an everything-as-remix understanding and non-ex nihilo basis for interaction and production is accepted, then remix practices are no longer just about certain works—critical or not—just as Free Beer is not merely about beer, but also about freedom and accessibility. Wanono (2015) stresses the revolutionary mentality and impulse associated with détournement over its particular acts; perhaps remix might be thought of in a similar way: as a guiding rubric for how artists, activists, scholars, scientists, and all other categories of creators and innovators should approach the work they do. By situating their work squarely in the context of the larger revolution against copyright and intellectual property, creators can, through the very act of creating, contribute to the project of pushing our collective perceptions of production, and the laws that govern and protect products, into a realm more in line with the realities of the digital, and approaching postcapitalist, era.

7. Acknowledgments

[7.1] I would like to thank Adrienne Russell for her insight, guidance, and feedback while brainstorming and working on this project. The article would not have materialized without the invaluable direction and encouragement she provided.